After Decades of Living with Pollution, Relocation Program Offers Corpus Christi Residents a Way Out

For decades, residents of Hillcrest were exposed to chemicals from nearby Refinery Row. With “mixed feelings,” residents are now moving out of the neighborhood.

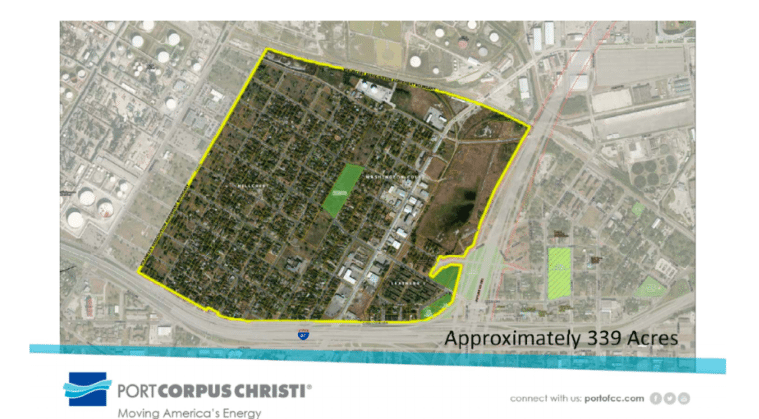

Above: Roughly 140 of Hillcrest's 450 residents have relocated and about 90 properties have been demolished.

For decades, the residents of Hillcrest — a poor, primarily Hispanic and black neighborhood on the north side of Corpus Christi — have been dealt blow after blow. In 1952, when Hillcrest and the adjacent Washington-Coles community were the only neighborhoods where black people were allowed to live, an explosion at a nearby tank farm forced residents to evacuate. In the following years, industrialization along the ship channel brought heavy polluting facilities, and residents breathed air laden with a slew of carcinogenic chemicals. In 2014, Citgo was fined $2 million for illegally operating tanks that were leaking benzene, only to have a federal appeals court overturn the ruling on a technicality.

Then, in 2015, came yet another gut punch. The Texas Department of Transportation wanted to relocate the aging Harbor Bridge to Hillcrest. The $1 billion project would’ve added another source of pollution in the form of traffic. This time, residents organized and filed a civil rights complaint against the state transportation agency. In a rare victory, the neighborhood activists secured a commitment from the Corpus Christi Port Authority in late 2015 to spend $20 million on a voluntary buyout program.

The buyouts are now seen by Hillcrest residents as the sole bright spot in an otherwise difficult situation. After about two years into the program, roughly 140 of the 450 residents have relocated and about 90 properties have been demolished. Residents have until May 2019 to decide whether to stay or go.

“Hillcrest is going to be number one no matter where I live.”

After years of reporting on the community’s battle with pollution, the Observer caught up with a few residents about their experience living in Hillcrest and what the decision to leave or stay means to them. Generally, residents agreed that the program offered them an opportunity to find better housing, which they didn’t imagine possible. But challenges remain. Some residents had credit issues, a few struggled to find a home in Corpus Christi’s tight housing market and others didn’t feel the program was equitable because of higher property taxes in new neighborhoods.

Roy Hall moved to the Hillcrest neighborhood in Corpus Christi in 1956, when he was 8. Despite segregation, the neighborhood was thriving. A number of black-owned businesses served the community, and there were churches, schools and parks. Ray Charles and B.B. King stopped by on tour. “We had everything,” Hall recalled. “We were self-contained.”

After six decades in Hillcrest, Hall moved to a three-bedroom house on the city’s south side a few weeks ago. He loves his new home, but said it was “heartbreaking” to leave the community he grew up in and that he has “mixed feelings” about it. He still feels pangs of nostalgia for his old neighborhood: “Hillcrest is going to be number one no matter where I live.”

Despite its challenges, the program has largely been successful at offering a way out for those who want it and could serve as a model for other fenceline communities struggling to cope with pollution. The Houston neighborhoods of Harrisburg, Manchester and Galena Park, as well as Port Arthur’s Westside, are among those in similar straits. In some cases, buyouts have been set up by corporations, not government, an arrangement fair housing advocates say is often not equitable or transparent.

The Hillcrest relocation program got off to a slow start. Once a resident decides to consider a buyout, their home is appraised and the Port of Corpus Christi calculates the cost of a comparable home in a different neighborhood, adding the difference to the buyout total. For example, if a house is appraised at $50,000 and the prospective property costs an additional $100,000, then the port authority offers to pay up to $150,000 for a new house. Theoretically, the price difference added to the buyout is supposed to compensate for the depressed property values in Hillcrest and Washington-Coles from years of segregation and neglect.

But residents found that with the havoc caused by Hurricane Harvey, as well as growth in the chemical industry and its workforce around the port, Corpus Christi was in the middle of a housing crunch. Affordable homes were snatched up quickly, and residents often lost to cash or single-mortgage buyers.

“The people who are leaving, I know them personally. I know their children and grandchildren. It’s devastating now to watch them leave.”

Many residents also had credit issues. When Rosie Ann Porter decided she wanted to join the relocation program, financial troubles from a decade ago came back to haunt her. Plus, with her arthritis, she needed a home that was move-in ready. When she did find a comparable house, it cost $11,000 more than the port authority was offering. Lenders were unwilling to loan her the relatively low amount. Eventually, one of her children helped her secure a deal. “I went through some trials and tribulations,” she said.

Daniel Peña is adamant that he’s staying. Peña co-founded Citizens Alliance for Fairness and Progress, a group that’s advocated for Hillcrest and fought against the refineries for years. Moving to a different, more expensive neighborhood would mean higher property taxes, he says — an added barrier some residents may not be able to overcome. Peña owns five properties in Hillcrest and rents them out. The relocation program doesn’t offer more than the appraisal value for landlords. The port offered him $29,000 for one house, he said.

“If I rented it out, I would get $9,000 a year,” he said. “Where in the world would I buy a house for $29,000? … They’re taking tenants away and leaving us with whomever.”

So Peña has chosen to stay, though he knows the bridge will bring more traffic and pollution. He also recognizes that with people moving out and houses being torn down, the neighborhood isn’t going to be the same. As part of the agreement, a new park is to be built in Washington-Coles, and there’s additional money for improvements to Hillcrest parks. But Erin Gaines, a Texas RioGrande Legal Aid attorney who filed the 2015 claim, said the deal “fell short” for those who were choosing to stay. “We would’ve liked to see a lot more for residents who are going to stay,” she said.

Peña says watching his community scatter across Corpus is upsetting. “Basically your whole neighborhood is destroyed,” he said. “The people who are leaving, I know them personally. I know their children and grandchildren. It’s devastating now to watch them leave.”