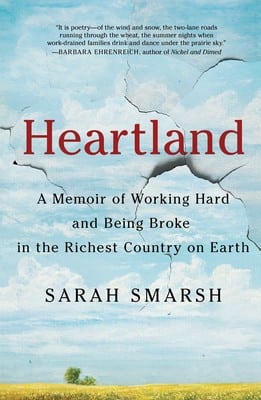

Heartland is an Honest, Poetic Meditation on Class in America

Journalist Sarah Smarsh’s book encapsulates what it’s like to grow up in the forgotten farm fields of America, artfully mixing anecdote with political context and societal commentary.

Above: Lawrence, Kansas

Having fun during a Kansas winter, as Sarah Smarsh writes in her new memoir, Heartland, requires creativity: “Lots of snow, no hills.” In one memorable scene, she recalls the time her grandfather Arnie hitched a beat-up canoe to an old pickup before gunning it down a dirt road past snow-covered fields. Smarsh sits at the back of the canoe on a floor mat covering a hole in the boat; the people in front sing Christmas carols, their beers sloshing and whiskey cups tipping as the truck accelerates. “Hold onto your butts!” Grandma Betty hollers.

The unusual canoe ride is a happy distraction for Smarsh and the rest of her family at their Kansas farm. More often than not, their lives are punctuated by long hours of low-paying labor, by shrinking crop prices, by hospital bills they don’t have the money to pay. Some people might call them white trash or rednecks. But people like them — poor country people — are still worth something, even if they don’t earn much. They ought to enjoy life a little, too, right?

by Sarah Smarsh

Scribner

$26; 304 pages

Maybe that’s why, of all the scenes vividly laid out in Heartland, this is my favorite. It’s gleeful yet dangerous. It’s an exemplar of the country ingenuity often tapped by people who have few financial means. It also serves as an upbeat counterpoint to the painful tales that a book about life in the forgotten farm fields of America can dredge up. Like when a casket holding great-grandma Dorothy is lowered into a graveyard plot and the hired men lose their grasp on the box. “It shifted to one side with a thud, and the casket’s buckles came partly undone, allowing the lid to pop open slightly,” Smarsh writes with characteristic precision. “The corpse’s face, mouth slightly agape, pressed against the opening. … Betty stared straight into her mother’s gray face with a pained but steady look.”

Heartland finds Smarsh, once a mud-spattered farm kid, coming to grips with who she is now — and who she might have been had she stayed the family course. The journalist researched the 300-page book over 15 years, reading old letters, digging through family photo albums and spending “countless” hours interviewing relatives to piece together her family’s history. Some of the stories she elicited — such as one regarding the exact moment of her conception — are deeply personal and were hard to obtain. “My family had a way of not discussing themselves or the past. The stories I know, I know because I asked and asked again,” she writes.

Smarsh seamlessly interweaves those tales with her own experiences and the political happenings of the day to tell a story that feels complete, honest and often poetic.

Heartland is shaped by the idea of separation. Smarsh’s family is separated from big-city life by more than just geography. They are fundamentally isolated by class: their wallets skinny, their beards caked in sawdust, their eyes blacked from another row with an angry, drunk husband. This is what some disdainfully call “flyover country,” and the difficulties — economic or otherwise — that shaped Smarsh’s childhood go unrecognized by folks everywhere else. “You can go a very long time in the country without being seen, which can be both a blessing and a problem,” she writes.

The book offers important insight into class. How does classism alter one’s self-worth? If enough cultural messaging tells a poor person, or a black person, or a woman, that they’re worth less than someone else, well, they might just start believing it. Heartland forces readers to consider how they value others and how they value themselves.

Smarsh seamlessly interweaves those tales with her own experiences and the political happenings of the day to make a book that feels complete, honest and often poetic.

If nothing else, you should read the book for Grandma Betty, a rail-thin, thrice-divorced, whip-smart woman who chain-smokes and works in the courthouse telling probationers how to stay on the right side of the law. Her work ethic and fiery spirit clearly leave an indelible mark on Smarsh, who gets a first taste of journalism while typing up “reports” and reading case files in Betty’s office. It’s hard to pick my favorite Betty scene from the book, so here’s a few:

- When a woman tells Betty, who’s just had foot surgery, that she shouldn’t have parked in a handicapped spot because, “You don’t look very handicapped to me.” Betty replies that injured foot or not, “I know one damn thing, I can still kick your fat ass with this foot!”

- When Betty, driving from the family farm with Smarsh in the passenger seat, decides to wave goodbye to everything out the window. “Goodbye, barn! Adios, garden! See you in the funny papers, mailbox!” A couple beats of silence. Then, “GOODBYE, WHEAT FIELD! GOODBYE CRAB APPLE TREES!”

- Or when Betty, in a somber moment in the basement, shows Smarsh where some cash is hidden in a jar, along with some trinkets and a .38-caliber pistol, “just in case” she dies. Then, gravely, she tells her granddaughter that she wants to be buried without a bra. “I hate the damn things,” Betty said. “You can burn ’em at my funeral.”

Heartland shines brightest in moments like these, when colorful anecdotes bring childhood memories vividly to life. Beyond their entertainment value, these stories flesh out nuanced characters in complex situations, dispelling stereotypes about the working class. Smarsh bookends these engaging tales with social commentary and historical information, though occasionally the former can get a tad repetitive. For example, she repeatedly hammers the point that poor women — particularly poor mothers — are likely to become dependent on violent men. It’s a sound observation, but Smarsh doesn’t need to spell the problem out so many times when the book’s anecdotes already do so. Heartland draws its strength from its storytelling and authority from its context and commentary; in a few situations, I would have preferred the ratio been slightly shifted to favor anecdote.

And while Heartland dwells on how the unenviable circumstances Smarsh was born into shaped her early life, the book seems to rush through how her background cropped up in her college years and in her career so far. How does she square her present life as a successful journalist with her past life as poor farm girl born into unenviable circumstances? She does touch on the subject, but I’d have liked to know more. Perhaps a follow-up is in order.

I’d read it.