To Catch a Rapist: Houston Leads on Testing Old Rape Kits

For years, Texas cops left nearly 20,000 rape kits untested while perpetrators went free. Now some agencies are confronting that injustice.

A version of this story ran in the October 2014 issue.

Wesley Bernard Gordon got nine free years. Houston cops had already seen plenty of Gordon, who kicked off his adult rap sheet with a weapons charge three weeks after he turned 18. By the time he was 30, Gordon had been charged with assault, burglary, car theft, marijuana possession, evading arrest and credit card abuse, pleading guilty several times. He was unquestionably a criminal. But his record did not, at the time, suggest he was a sexual predator.

Then he broke into an apartment in south-central Houston. It was Friday, Aug. 8, 2003, and Gordon found Pearl (not her real name) sitting at her dining room table paying bills. Pearl was 77 years old and legally blind. “He followed me home from the grocery store,” Pearl says. “I didn’t even see him. He was waiting just inside the door. When I got up, he grabbed me from behind.” Gordon dragged Pearl to her bedroom, punched her in the face and raped her as she prayed to survive. Then, according to court records, he stole her purse and the contents of her coin jar and piggy bank.

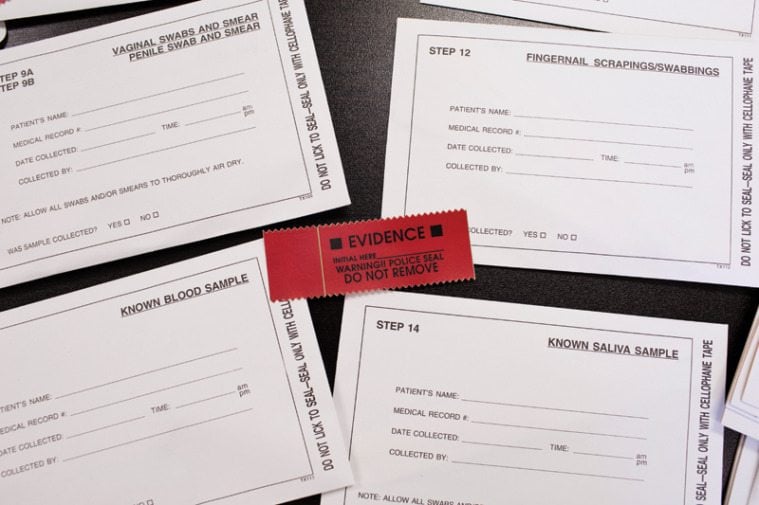

When Gordon left, Pearl did what about 725 Houstonians do every year and countless more do not: She reported the rape to police. Then she went to Memorial Hermann Southwest Hospital, where a specially trained nurse examined her and completed a sexual assault evidence collection kit, also known as a rape kit. Court documents show the finished kit contained swabs of Pearl’s vagina, anus, and the inside of her cheek, along with samples of her blood and saliva. These were enclosed in a sturdy white cardboard box, about the size of a children’s shoebox, sealed with red tape that said “EVIDENCE,” and delivered to the Houston Police Department (HPD).

There, the box was mislabeled and forgotten. The swabs and samples of Pearl’s violated body sat in the HPD property room with thousands of others like them, untested and gathering dust, for almost a decade.

Pearl’s was one of more than 6,660 sexual assault kits that Houston police declined to analyze until recently. Like most victims, Pearl thought police had done everything possible to catch her rapist, including having her kit analyzed at the time of the attack. In fact, she didn’t know her kit hadn’t been tested until the Observer told her during a recent interview. “I just assumed he eluded them for that long,” she says. “In nine years, I’m sure he was doing that to other people.”

What happened to Pearl’s kit isn’t unusual—in Houston or anywhere else. Though the technology to analyze DNA has been around for decades, hundreds of thousands of sexual assault kits all over the country went untested because investigators didn’t consider them important. Many times, officers shelved the evidence and blamed, disbelieved or otherwise alienated victims, then closed their cases.

Victims’ rights advocates call this a second betrayal. It takes courage, hours after an assault, to let a stranger examine your body, to treat it as the crime scene it has become, inspecting, probing and swabbing it precisely where it has just been trespassed. People do this because they believe it will help convict the person who hurt them. But in Texas, thousands of times, the kits were shelved instead.

Texas is still trying to figure out how often that happened. In 2011, lawmakers passed a bill by state Sen. Wendy Davis requiring every law enforcement agency to tally and report its untested sexual assault kits. The bill also mandated that law enforcement agencies submit kits to a crime lab within 30 days. At the time, the Department of Public Safety (DPS) estimated up to 20,000 kits like Pearl’s might be warehoused all over the state. Now, that number is looking low. As of July, only 146 of Texas’s 2,647 law enforcement agencies had reported their totals, but the statewide count of untested rape kits was already nearly 19,000.

That includes the major cities—Dallas (4,144), San Antonio (2,077), Fort Worth (1,018) and Austin (407). Houston alone contributed almost one-third of the outstanding kits. But seven of the 20 biggest cities in Texas, including Arlington, Laredo, Plano, Irving and Brownsville, have yet to report. Their tallies—along with those of the 2,500 other missing agencies of assorted sizes—will likely boost the state’s total beyond the estimated 20,000.

One of the reasons Houston has so many kits is that its police department never threw any away. Its oldest kits date back to 1982, three years before the advent of DNA testing, when kits were useful only for crude evaluations such as matching blood type. Retaining that evidence preserved a chance for future justice, but it also made Houston look terrible when untested-kit numbers were made public.

The other thing Houston’s giant tally doesn’t reflect is that, over the past few years, the city has transformed from a scandal-plagued example of how not to handle rape evidence to a national leader in tackling the problem of untested kits. That’s largely thanks to a groundbreaking collaboration between the Houston Police Department and a host of local entities that serve sexual assault survivors. Fostered by a national grant, the group has spent three years investigating how so many untested kits accumulated and, based on its findings, making changes to keep such injustices from ever happening again.

But while studying how to set things right, Houston also began to realize just how wrong it had gone.

Using $4.4 million in grants and city funds, HPD tested or outsourced the testing of all its kits. That process, only recently completed, has already led to more than 20 arrests.

One of those was Wesley Bernard Gordon. Pearl was right—in the nine years after raping her, Gordon allegedly committed four other sexual assaults, including the rape of a homeless woman. Had police bothered to test Pearl’s rape kit soon after the attack, it’s possible those assaults would have never occurred. Instead, Gordon was free until recently, when HPD finally tested Pearl’s kit. In September 2013, a full decade after Pearl gave police the evidence that could definitively identify her rapist, a jury sentenced Gordon to life in prison.

The first U.S. conviction based on DNA evidence was of a Florida rapist in 1987. Initially, DNA was only useful when law enforcement had a known suspect, but that changed in 1994 when Congress established a national database of genetic material. Texas founded its own just a year later, as did every state, eventually, and together these databases seeded what would become CODIS: the Combined DNA Index System.

CODIS was a game-changer. Originally populated with samples from crime scenes, unidentified human remains and convicted offenders, the national database let police link cases to suspects even with no other information. Soon, several states including Texas passed laws extending mandatory DNA collection to include people arrested for or charged with certain crimes. By 2010, CODIS had cataloged the DNA of more than 8.7 million people.

After the database was born, demand for DNA analysis exploded, and crime labs couldn’t keep up. In 2001, victims’ rights groups warned of growing backlogs of forensic evidence at labs around the country. Three years later, a hounded Congress dedicated hundreds of millions of dollars to eliminating the backlogs.

For victims whose rapists remained free for years, even as the evidence to convict them sat on a shelf in police custody, no apology is enough.

The trouble is, demand for DNA testing in many places continued to outstrip growth in crime-lab capacity. Backlogs, once cleared, would quickly form again. In 2009, a CBS News investigation found that rape kits in Alabama and Illinois took, on average, six months to process. In Missouri, the wait was almost a year.

These kits—the ones submitted by law enforcement to crime labs for analysis but not returned for more than 30 days—are what the National Institute of Justice, the research arm of the Department of Justice, considers “backlogged.”

But that’s not what happened in Texas.

Rather, most of the 19,000 kits reported (so far) never saw the inside of a lab because a sexual assault investigator made the decision not to have them tested. Victims who endure DNA collection may understandably assume it will be analyzed as part of the investigative process, but until recently, law enforcement officers could choose whether to test a kit. Often, they chose not to.

This was by no means limited to Texas. A 2011 survey by the National Institute of Justice found that, on average, nearly one in five recent unsolved rape cases nationally contain forensic evidence for which police never requested analysis.

The language used to talk about untested kits can obscure this deliberateness. If only for brevity, law enforcement and victims’ rights advocates alike have embraced the term “backlog” to describe all untested kits, but this can wrongly suggest that testing was attempted or intended. The term “backlog” implies the problem was simply a lack of resources instead of a conscious decision by police not to test. Similarly, untested kits are usually described as having been “discovered,” often “discovered in a warehouse,” as if evidence for thousands of sexual assault cases had been misplaced. That’s misleading, too.

“I think on some level jurisdictions love to use the word ‘discovered,’” says Sarah Tofte, vice president of policy and advocacy for the national Joyful Heart Foundation, “because that makes them feel, in a way, a little bit better, and maybe look a little less culpable.” The Joyful Heart Foundation runs the website EndtheBacklog.org, a clearinghouse for information on the quest to test all kits. Tofte says, “I think when people hear, ‘Oh, they discovered a backlog,’ they imagine there was some abandoned meat locker somewhere in a field, and they opened it and said, ‘Oh my gosh! There are all these untested rape kits! We had no idea.’ But yes, jurisdictions know. They know because it’s their policy. If their policy is, ‘Don’t send everything to the lab,’ there shouldn’t be a surprise when there’s a backlog.”

Beyond the presence or absence of a test-all-kits policy, sexual assault investigators have historically had little codified guidance on when to submit a kit to the lab. This latitude allowed prejudices and misconceptions about sexual assault to interfere with justice.

Tofte says that while expense plays a role—kits can cost $1,000 to test, and Houston takes in about 1,000 kits a year—that’s not the bottom line. “The real driver behind why some jurisdictions have accumulated such a large number of untested kits,” Tofte says, “is that, if you’re not serious about a case, you’re not going to have the rape kit tested. … When you’re getting to look at some of the case files that are connected to the backlogs, what you see is usually very dismissive attitudes by law enforcement. Usually, very little investigation is done. The case files consist of maybe one or two pages at most, and what they consist of is the initial interview by the detective with the victim and that’s it. … What you see is this incredible scrutiny on the victim’s credibility, the victim’s background, socioeconomic status. You see a lot of, ‘Hey, as a detective, do I believe this person? Do I think this person is really worth moving this case forward?’”

Houston had this problem. That was one of the main findings of the interdisciplinary group that’s been studying Houston’s untested kits for three years, though the group’s members wouldn’t put it so bluntly. “It’s not that we were doing bad,” explains HPD Assistant Chief Mary Lentschke. “But we wanted to do better.”

In 2010—before Davis’ bill—HPD, on its own initiative, had already implemented a test-all-kits policy. Then it successfully applied for a competitive grant from the National Institute of Justice. The grant, awarded just to Houston and Detroit, provided funds for the city not only to inventory its kits, but to study why so many went untested for so long, and to institute reforms. This wasn’t a secretive internal probe, either. Since early 2011, guided by the grant, HPD has hosted regular meetings of a diverse team of researchers, victims’ advocates, health care workers, forensic scientists, prosecutors and police brass, all dedicated to improving their response to sexual-assault survivors in Houston. When the grant ends in October, the group plans to continue its work independently.

Before sitting down together as part of the straightforwardly named Sexual Assault Kit Action-Research Task Force, many of these parties hadn’t previously communicated, let alone collaborated. Others, like victims’ rights advocates and some HPD investigators, were downright adversarial. As part of the group’s research, social scientists surveyed the attitudes of people in the justice system toward victims’ rights advocates and found that investigators in HPD’s Adult Sex Crimes Unit were particularly averse to outside meddling. One investigator told the group’s researchers, “…[Advocates] lead the woman to believe things that aren’t true.” Another complained, “[Advocates] have an agenda and take the woman’s side immediately.”

Undeterred, HPD moved forward with a plan to add a “justice advocate” to the Adult Sex Crimes Unit: a master’s-level social worker charged with improving investigators’ interactions with victims. The advocate, Emily Burton-Blank, was installed within earshot of investigators—a major breach of traditional police insularity—and investigators were required to involve her when contacting victims prone to dropping out of the process, such as people who are homeless or suffering from mental illness.

“Where we saw a large issue was the fact that a lot of people were dropping out of the system shortly after reporting [their rapes],” says HPD Assistant Chief Lentschke. “So we looked at that. How can we keep them in longer? Emily [the advocate] is a living, breathing idea. She’s done magnificent. And the investigators who were so anti-advocate … now they absolutely love her. That’s a huge turnaround.”

Justice Advocate Emily Burton-Blank discusses her work with survivors and investigators of sexual assault crimes.

Sonia Corrales, chief program officer for the Houston Area Women’s Center, agrees. “Whenever we send a survivor [to HPD],” she says, “we know that when they talk to Emily, they’re getting really great service.”

The justice advocate position was originally slated to last less than a year and be funded only through the grant, but HPD officials quickly found the results so impressive that they made the position permanent and committed to hiring more advocates in the future.

It’s one of several steps HPD has taken to improve its treatment of sexual-assault survivors. New policies now require investigators to go into the field to investigate assaults rather than closing cases if victims fail to return phone calls or respond to a letter. The adult unit recently set aside a private room in which to take victims’ statements rather than interviewing them in the open, surrounded by other staff and ringing phones. And investigators have gotten new training, including education on the neurobiology of trauma so they can better recognize and respond to it.

But most important, HPD leadership has committed to ending the culture of victim blaming.

The change HPD made, explains Captain Jennifer Evans, who heads the Special Victims Division, “wasn’t so much of how to do an investigation, because our investigators did good investigations. It wasn’t that. It was how you interacted with the victim. How you gave feedback to what they were telling you. We just try to tell the [investigators], just go with, ‘They’re telling the truth. Let’s take it from there.’ Because so many times, people—all of us, not just investigators—are skeptical or whatever. [We tell them], ‘Let that go. We expect you to be a professional, be compassionate and give them resources. Try to contact them. Put them in touch with help.’ It wasn’t so much how to do investigations, it was changing the mindset.”

“You know, when you’re trying to turn a ship a little bit, and change that culture a little bit, it takes a lot,” says Assistant Chief Lentschke. “Trying to change that direction takes support from within the organization. It takes constant messaging, constant explanation of the expectations, and then you’ve got to have the oversight to make sure your investigators are doing those things and taking the time. So this is ongoing. By no means when this grant ends are we done. … We still have a long way to go. So this is a constant. We’re not going to have a nice, neat conclusion for you. But I can tell you, the ship is turning.”

While HPD acknowledges its history of victim blaming, lack of investigator interest is not among the reasons listed by the research group for why so many kits went untested. Rather, the group reports that investigators declined to analyze kits because the suspect was known to the victim, consent was at issue, the suspect was arrested and charged using other evidence, or the victim couldn’t be located or wasn’t willing to prosecute.

The 19,000 kits reported (so far) never saw the inside of a lab because a sexual assault investigator made the decision not to have them tested.

None of those is a good excuse, says Tofte: “What we’ve learned, especially over the last five or six years, is how incredibly valuable DNA testing can be in all kinds of cases. I think police have a lot of misconceptions about serial rapists, [thinking], ‘Oh, they just rape strangers.’ And oftentimes they’re raping acquaintances as well and setting up a pattern, but it’s going undetected because no one sends in the evidence for testing to connect the cases.”

Corrales is among those who believe all kits should be tested on principle. When survivors go to the hospital and endure evidence collection, she says, “they’re under the impression that somebody is going to do something with that kit. And they deserve that. They deserve for the kit to be tested, and to be informed of what happens with that kit, whether it gets prosecuted or not, whether the statute of limitations has passed—survivors deserve to know.”

All of HPD’s old rape kits have now been tested and, as of mid-August, almost 2,500 eligible DNA samples had been uploaded to CODIS. Staggeringly, 933 of those—more than one-third—were “hits,” meaning they matched a known offender already in the database.

That doesn’t mean these were all serial rapists. Authorities are required to collect DNA samples from all felons, meaning many people have CODIS offender profiles because of drug convictions or other nonviolent crimes. Also, Texas and 29 other states take DNA from anyone formally charged with—or, in some cases, merely arrested for—certain felonies, so not everyone in CODIS has been convicted of a crime. Finally, a rape kit going untested doesn’t mean the rapist went free. If police declined to test the kit because the attacker’s identity was known, a CODIS hit may just confirm they got the right guy. As of June, 83 of the CODIS hits in Houston were such arrest confirmations. HPD has also stated that none of the results suggests a wrongful conviction.

Another 34 kits had what are called case-to-case matches. That means the DNA found in the rape kit matched DNA already uploaded from evidence taken in a different unsolved crime—another rape kit, perhaps, or blood from a break-in—but for which there’s no suspect yet. If the offender is later convicted of any felony, his DNA will link him to the previous crimes.

That said, Houston’s recently tested kits have certainly delivered forensic evidence that could have been used sooner, as demonstrated by the 20 new arrests. Some hits have resulted in new charges but not a new arrest because the suspect was already incarcerated for a different crime, such as in the case of Roland Ali Westbrooks. He raped a 16-year-old girl in her bed in 1995, but HPD didn’t test the kit until 2011, when Westbrooks was already in prison for a rape committed in 1997.

It’s possible Westbrooks couldn’t have been identified by testing the kit in 1995, when the DNA database was only a year old and not very well-populated. But if HPD had tested its older kits sooner, his victim would at least know her attacker was locked away. That’s important, says Annette Burrhus-Clay, executive director of the Texas Association Against Sexual Assault. “They would have had the peace of mind of knowing that person’s sitting in jail for something, instead of worrying that person’s coming back to get them,” she says.

HPD says it doesn’t know how many of the CODIS hits can be linked to offenders convicted of previous sex crimes or how many suspects were linked to more than one kit. But it has identified at least one possible serial rapist. In April, Herman Ray Whitfield Jr. was charged with four counts of aggravated sexual assault for three rapes allegedly committed from 1992 to 1994 and one in 2008. Whitfield was sentenced to 30 years in prison for kidnapping in 1994 but was paroled in 2006. If HPD had tested its kits sooner, Whitfield would likely not have been released. One of the victims was only 12 years old.

HPD has assigned a special unit to pursue cases with CODIS hits and has committed to reviewing every case that had an untested kit, even if the results provided no new evidence. Investigators are attempting to contact all victims whose evidence yielded a CODIS hit and pursue prosecution if possible. HPD also set up a hotline for victims to find out if their kits were among the untested and learn about the results.

Captain Evans says these efforts, both to use the new evidence and to change HPD’s culture, are having an impact. “One of the things that [the group’s researchers] said was that survivors complained about their initial contact with law enforcement, that they didn’t feel they were believed and [police] were rude and judgmental,” Evans says. “However, they felt that the second time they were contacted”—that is, after their kit was tested and had a CODIS hit—“the officers were sensitive, compassionate and cared. One [victim] did say that the officer said, ‘I’m sorry this happened to you. I’m sorry it wasn’t taken care of before. But I’m here now. Let’s do what we can.’ She really felt that that was huge to her, to acknowledge that.”

While Houston is confronting its rape kit problem, many other cities in Texas and nationwide are not. It’s difficult to estimate how many untested kits Texas will turn out to have. Some cities that have completed their audits found tiny numbers of untested kits relative to their size, such as El Paso—its 27 untested kits amount to about four per 100,000 residents. Others found the opposite. Amarillo is one-third the size of El Paso but reported 952 untested kits, or about five per 1,000 residents—more than 100 times El Paso’s ratio.

That doesn’t necessarily mean El Paso was 100 times more diligent than Amarillo about testing rape kits, though. Law enforcement agencies have had wildly varying policies about when and how long to keep evidence; some kits may simply have been thrown away. Not until Davis’ bill were practices for keeping and managing sexual assault kits standardized. Now police are required to test kits within 30 days of receipt, compare the results with state and national DNA databases, and keep the kits for at least two years. Agencies were also supposed to submit all their untested kits dating from 1996 or later to DPS or another crime lab by April 2012, but clearly that hasn’t happened. Without the kits, DPS couldn’t meet the other deadline set by Davis’ bill—to have all the old evidence analyzed by September of this year.

“We’re not going to have a nice, neat conclusion for you. But I can tell you, the ship is turning.”

There are two major problems with Davis’ bill, says Burrhus-Clay of the Texas Association Against Sexual Assault: money and enforcement. The Legislature dedicated $11 million for the effort, but at $1,000 per test, that’s not likely to be enough. “One of the things that was missing from the bill is the fact that there was no penalty for not participating in the audit,” Burrhus-Clay says. With only 146 agencies reporting, she says, “That’s giving us a better picture but certainly not the full picture. But at the same time, I don’t necessarily advocate for something that’s punitive for these departments, because it’s a matter of resources. We can’t put the hammer down on these departments and then not give them the resources with which to comply. At some point, we’re going to realize that $11 million, while incredibly generous and certainly a nice place to start, may not be adequate.” But again, the Legislature needs cities to complete their test audits to know how much money to appropriate. “Until we get all that data,” she says, “you’re kind of guessing at how big the problem is and how much money and time it will take.”

The other crucial piece of this search for tardy justice is likely impossible to legislate: a commitment to investigation. Law enforcement agencies can be forced to test their kits but not to change the culture that left them untested in the first place. “They didn’t really believe they needed to test all these kits,” Tofte says. “So if that’s their posture going into it and nothing really changes their mind, and they’re not even really examining the leads they’re getting, you’re probably not going to get the depth of reform you need to make a difference. If you don’t do anything with the leads you get, you might as well have not tested the kit.”

That’s why Tofte says examples like Houston and Detroit are so important. “You have very powerful data that I think really started to turn the tide,” Tofte says. The number of CODIS hits “really got other police and prosecutors thinking, ‘Oh my gosh. Those results are pretty astounding.’ … You see a little bit more of jurisdictions generating [reform] themselves, not having to have a lot of outside pressure.”

HPD’s reforms, and the models offered by their success, will unquestionably benefit future victims. And Texas, being one of the first states to mandate timely testing of all sexual assault kits, seems unlikely to allow vast stores of evidence to go unanalyzed again. This is all to the good. But for victims whose rapists remained free for years, even as the evidence to convict them sat on a shelf in police custody, no apology is enough.