In Boerne, a Youth Suicide Prevention Effort that May Actually Work

Boerne ISD was once in the grips of a student suicide crisis, but now a prevention program has kept the district suicide-free for the last three years.

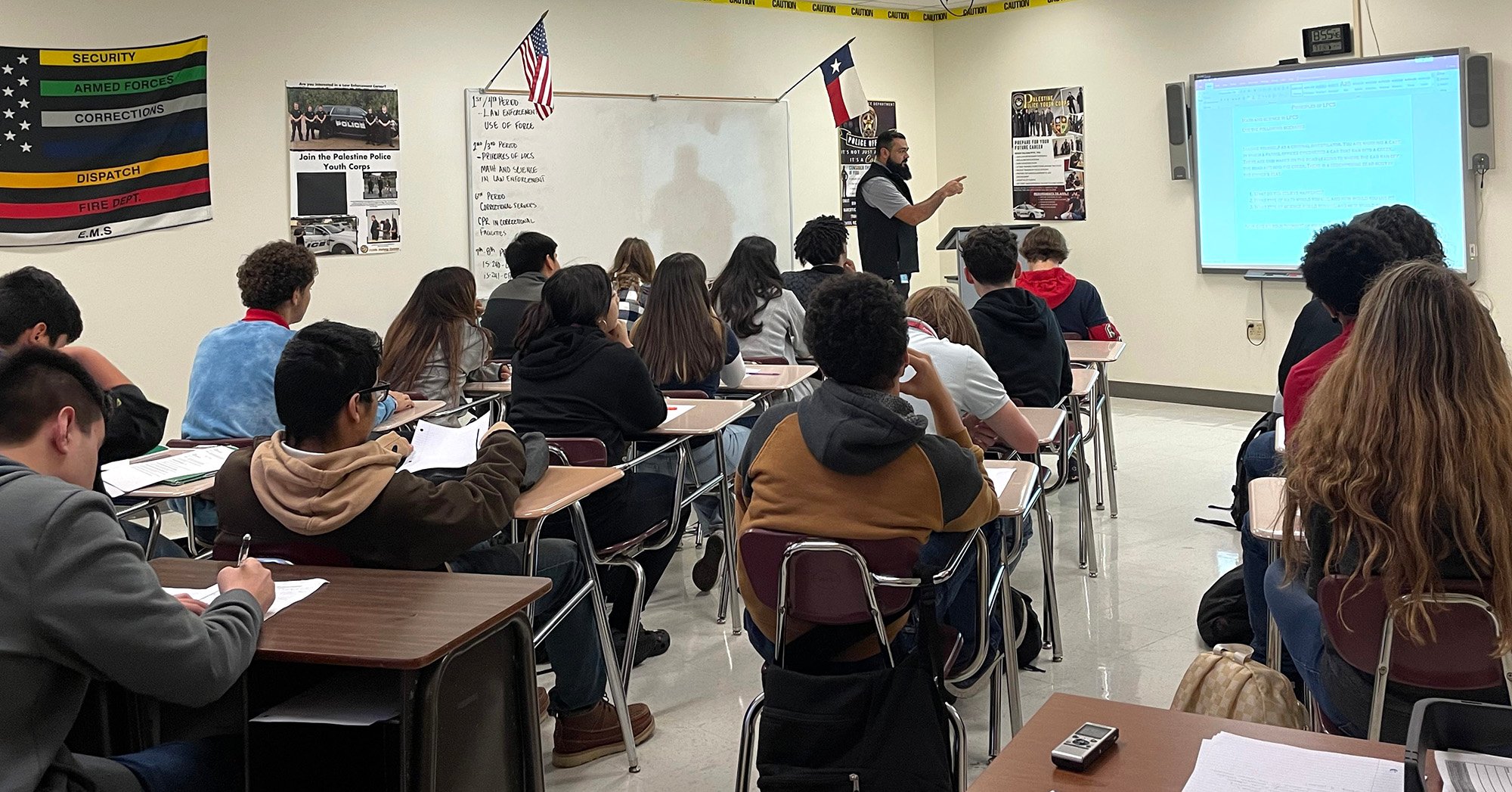

Above: Boerne ISD’s training regime goes beyond the cursory requirements of the state law.

A decade ago, Boerne ISD — an 8,700-student district on the outskirts of San Antonio — was in crisis. Students were inexplicably killing themselves at the rate of almost one per year from 2006 to 2014. Among them was a 16-year-old cross-country runner and student council representative at Champion High School who took his own life in 2009. At the same school in 2014, a 16-year-old Boy Scout and community theater actor also died by suicide. At least seven students in the district killed themselves in that 9-year period, though the number could be higher; local records on the deaths are incomplete.

“The suicide of a teenager shakes our small community. To lose one [child] devastates us,” said Holly Robles, who oversees the district’s suicide prevention initiatives. “We were worried.”

But now it seems as if district officials may have found a fix. In 2015, Robles pulled together a task force of teachers, parents, mental health professionals and others in a desperate attempt to stem the tide of youth suicides in the San Antonio suburb. They agreed to ramp up suicide prevention training for educators and school employees beyond what the state requires; to teach kids about suicide warning factors in health education classes; and to establish a database to identify and track students in crisis so they don’t slip through the cracks. If a student is hospitalized for a suicide attempt, or if another student reports that a peer might be suicidal, Robles gets a call.

It’s the only system of its kind in the state that Robles knows of. “You don’t see many school districts taking this much initiative in suicide prevention. It’s an aggressive plan and it hits at every level,” she said.

Though it’s hard to know for sure, the effort appears to be working: No Boerne ISD students have taken their own lives since the system was put in place in the 2015-16 school year.

The district’s apparent success is an outlier among Texas schools, where youth ages 13-17 are nearly twice as likely to attempt suicide than the national average. Though no state database exists to track suicides of Texas public school students, federal data shows that 134 Texas kids in that age group killed themselves in 2016, a 48-percent increase from five years ago.

“The suicide of a teenager shakes our small community. To lose one [child] devastates us.”

As youth suicide attempts have hit record highs in Texas, state lawmakers have passed a weak version of legislation that’s been adopted by other states to train teachers on suicide prevention. While Texas school districts are required to provide training to educators under a law passed in 2015, lack of enforcement and oversight means that no state agency has any idea if teachers are actually getting the mandated training. As the Observer reported last month, the training isn’t required for teachers to maintain their professional license. And while school districts must maintain records of which teachers have been trained, state law doesn’t direct the Texas Education Agency to review those lists.

Boerne ISD’s training regime goes beyond the cursory requirements of the state law, which mandated one-time suicide prevention training for existing teachers in the 2015-16 school year and training for new teachers in subsequent years. For instance, all Boerne ISD staff — including cafeteria workers, janitors and bus drivers — must participate in the training every year, regardless of whether they’ve taken it before. And there’s no state requirement for teaching kids about warning signs in health class. But prevention experts say students sometimes are more apt to signal problems to peers than they are to confide in administrators.

There are also no state rules dictating that districts keep track of at-risk students, though such record-keeping gives administrators crucial information regarding students’ histories, Boerne officials say. Students who are identified as at-risk are referred to counselors who assess their relative level of risk and develop a plan. That could include meeting with parents, a referral for outpatient mental health services or transfer to inpatient care in serious cases.

In the Boerne program’s inaugural year, 76 high school students were identified as being at risk for suicide, Robles said. In its second year, 380 students were identified, though that number fell to 196 last year. That’s not a sign that fewer kids are actually at risk, she said, but rather that some campuses need to increase identification efforts.

“Suicide prevention planning for schools takes a team approach, which Boerne has done remarkably well,” said Lisa Sullivan of the Texas Suicide Prevention Council. She added that the district’s success has the potential to be replicated elsewhere in the state.

“It’s our hope that every school in Texas and the nation use this model,” Robles said. “Every student in our school is important to us, and we don’t want to lose a single one to suicide.”

Need help? In the United States, call 1-800-273-8255 for the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline.