The Truth About How Pregnant Women Are Treated in Texas County Jails

A version of this story ran in the August 2015 issue.

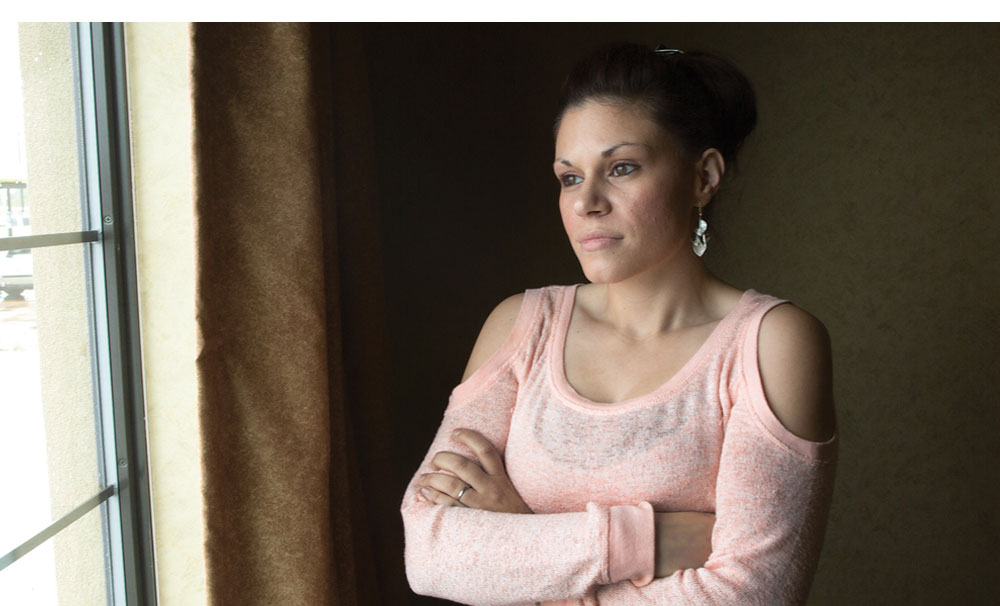

Nicole Guerrero had been awake all night, writhing and moaning in pain from the baby that would soon be born, when she heard the unmistakable sounds of breakfast in jail. It was around 5 a.m. at the Wichita County Jail and she could hear guards and inmates clattering trays and making small talk. At this point, she had been in pain for almost 12 hours, and despite her cries for help, the jail staff didn’t seem alarmed. Alone in a medical cell, Guerrero knew she couldn’t wait any longer to start pushing. She loosened the Velcro of her one-piece jumpsuit, soaked with blood, and reached down and felt the head of her baby.

She cried out for help, and a nearby guard arrived just in time to help guide the baby onto Guerrero’s thin sleeping mat on the floor. The baby, whom Guerrero named Myrah after an inmate who had been kind to her, was born dark purple and unresponsive, the umbilical cord wrapped around her neck.

The Texas Commission on Jail Standards, responsible for evaluating Texas’ 243 jails with just four full-time inspectors and an annual budget of $900,000, can barely keep up.

“I can’t even tell you what she looked like,” Guerrero said. “I already knew she was gone.” Paramedics soon arrived and took Nicole and Myrah to the county hospital, where Myrah was pronounced dead at around 6:30 a.m.

In June 2014, two years after Myrah’s death, Guerrero filed a lawsuit against the county jail, Wichita County Sheriff David Duke, the private company that provides medical care to inmates, and the nurse on duty, claiming that she received inadequate care, and that her pleas and signs of labor were ignored for hours. The lawsuit also claims the jail didn’t have a plan in place for women who go into labor while incarcerated. Medical experts tapped by Guerrero’s attorney concluded that Myrah’s death could have been prevented by simply taking Guerrero to the hospital when she cried for help.

Guerrero’s horrific experience is an extreme example of how poorly pregnant women are sometimes treated while in jail. The number of incarcerated women in the U.S. has quadrupled since 1980, but jails and prisons have often neglected the needs and treatment of pregnant inmates. In Texas, 300 to 500 pregnant women are booked into county jails each month, and dozens gave birth while in custody last year. Women report not getting enough food. They say the notoriously uncomfortable sleeping mats cause back pain. And they feel mistreated and disrespected by guards. One woman in a Travis County lockup last year said she was shackled to her hospital bed while delivering her baby.

The problems are poorly documented, some jails are ill-equipped to handle pregnancy emergencies, and services for pregnant women vary wildly depending on a county jail’s budget and the availability of medical providers. The Texas Commission on Jail Standards, responsible for evaluating Texas’ 243 jails with just four full-time inspectors and an annual budget of $900,000, can barely keep up. Commission officials didn’t learn of Guerrero’s experience until two years after it happened, and only then because of the lawsuit. Similarly, the agency doesn’t find out if a pregnant woman is shackled during labor, delivery or recovery unless she files a formal complaint.

As Guerrero and others have come forward with their stories, activists have pushed for better treatment of pregnant inmates. Thanks to their efforts, we’re just now getting a clearer picture of pregnancy behind bars.

Nicole Guerrero was the kind of small-town, young athlete whose prowess begged for a nickname.

As a girl growing up in Burkburnett, near Wichita Falls, she played basketball and softball on Little League and regional teams. She was a star three-point shooter and played shortstop for her softball team, where she was known for hitting grand slams. She danced, performed gymnastics and was constantly on the road with her mom traveling to nearby North Texas towns for tournaments. Her teammates called her “Rocket.” Her mother, Leesa Reyes, remembers Guerrero as a quiet, reserved kid with a lot of potential.

“She was always winning something, accomplishing something, being recognized for something,” Reyes said of her daughter. “She stood out.”

At 16, her life took a sudden turn. After several sports-related injuries, Guerrero was prescribed painkillers, and she quickly became addicted. She experimented with prescription drugs, quit sports, dropped out of high school, and had a miscarriage after an unplanned pregnancy. She had three children over the next decade of her troubled life, but, unable to care for them while in the throes of addiction, she voluntarily gave up custody of all three.

Guerrero was in and out of jail for minor offenses, including drug possession and stealing from stores while high on painkillers. On June 2, 2012, Guerrero was arrested and booked into Wichita County Jail for violating her probation for a drug conviction. She was 26 years old and eight months pregnant.

Nine days into her stay, Guerrero saw the OB-GYN who contracts with the Wichita County Jail, and everything seemed normal. The doctor prescribed antibiotics for a vaginal infection, listened to the baby’s heartbeat and then sent her back to jail, according to the lawsuit.

With pregnancy, though, circumstances can change quickly. At around 6:30 p.m. that evening, Guerrero began cramping and experiencing lower back pain. She was also leaking fluids, including blood. Panicked, she requested that a nurse check on her. The nurse on duty, identified as “Nurse Amanda” in the lawsuit, listened to the baby’s heartbeat and told her it sounded fine. She gave Guerrero the antibiotics prescribed by the doctor earlier that day.

By 10 p.m., as the jail locked down for the night, the pain had grown more intense. According to Guerrero and the statements of on-duty officers provided to the Observer by Guerrero’s attorney, her cellmates repeatedly pushed the medical emergency button, calling for help on her behalf. Frightened and in agonizing pain, Guerrero lay curled up on her bunk bed.

“I couldn’t move,” she said. Around midnight, according to a statement by a guard identified as “[Detention Officer] Boyd,” an unnamed technician checked Guerrero’s vital signs, but the tech “never informed [Boyd] on what was discovered.” LaDonna Anderson, a licensed vocational nurse employed by Correctional Healthcare Management, had taken over for “Nurse Amanda” by then. The private company, now called Correct Care Solutions, has a $1.5 million annual contract with Wichita County to provide medical services to inmates, and relies heavily on licensed vocational nurses to staff the jail. While the county has privatized on-site services for pregnant women, it remains responsible

for off-site specialty care, including obstetrics and gynecology.

When Guerrero asked Anderson for help throughout the night, Anderson told her that she was fine, having seen a doctor earlier that day, according to the lawsuit.

Finally, at around 3 a.m., officers moved Guerrero to the jail’s medical cell. She remembers being wheeled down the hall in a wheelchair, carrying her bloody sanitary pads, her sleeping mat and her box of personal belongings as other inmates and guards mocked her.

The medical cell, which Guerrero dubbed “the cage,” had no bed, so she laid her mat on the cold, concrete floor. According to the lawsuit, Anderson didn’t examine Guerrero when she arrived at the medical cell, despite Guerrero showing her the blood-soaked sanitary pads.

“It’s OK, Nicole. Take a breath,” Guerrero heard Anderson say through the Plexiglas window dividing the cell and nurse’s station. The lawsuit also says that Anderson told Guerrero that she called the doctor to inform him of Guerrero’s condition. Anderson’s attorney didn’t return multiple messages left by the Observer.

“In my mind, I think she’s judging me as a crazy inmate begging for attention, just being a drama queen to give them hell or something,” Guerrero said. “At this point, I’m thinking that I have to coach myself through this.”

At around 5 a.m., as the jail sprung to life, Guerrero knew she was in labor. She begged Anderson to help her and, according to the lawsuit, Anderson told Guerrero she would “be right back,” then went to check on male inmates on a different floor.

Boyd was nearby, passing out breakfast trays to inmates. According to the officer’s statement, Boyd “heard Guerrero screaming and stating ‘Help me!’” Boyd went to the medical cell. “I then entered the observation tank and observed the baby’s head was sticking out,” the statement reads. Then the officer called for Anderson before kneeling down.

Guerrero, with Boyd’s help, delivered Myrah on the sleeping mat.

Anderson arrived at the medical cell several minutes later. She unwrapped the cord from Myrah’s neck while guards unsuccessfully looked for a bulb syringe to use on the baby’s nose and mouth. Officers wrapped Myrah in a towel while waiting for the paramedics to arrive.

Medical experts analyzing the case for Guerrero concluded that she was not properly assessed or monitored by Anderson. Ann Schutt-Aine, a doctor and OB-GYN professor at Baylor College of Medicine, wrote in her evaluation that the staff’s inaction “directly led” to Myrah’s death. Guerrero’s signs of labor weren’t recognized, and she should have been taken to a hospital, where labor, as well as an infection of Guerrero’s uterus, would have been properly diagnosed, Schutt-Aine concluded. At a hospital, doctors could have detected Myrah’s distress and performed a C-section.

The number of incarcerated women in the U.S. has quadrupled since 1980, but jails and prisons have often neglected the needs and treatment of pregnant inmates.

Jacquelyn Moore, a registered nurse and correctional health expert evaluating the case for Guerrero, echoed Schutt-Aine’s conclusions. Moore wrote that Anderson didn’t document Guerrero’s complaints or her attempt to contact a physician. She also wrote that if Anderson had properly examined Guerrero, “the nurse could have unwrapped the cord prior to delivery, and could have … saved the baby.”

Wichita County Judge Woody Gossom, the sheriff’s office and Correct Care Solutions all declined to respond to questions for this story, citing a policy of not commenting on pending litigation.

However, in responses to Guerrero’s lawsuit, the county and sheriff’s office repeatedly contend that Guerrero did see a doctor while in custody, as the county health plan dictates, and that neither the county nor the sheriff violated her constitutional rights.

Thomas Kerr, a former sheriff and jail administrator now with the Texas Association of Counties, analyzed the case for Wichita County. He found no fault with the county, its contract with Correct Care Solutions, or the health care protocol in place for inmates, and concluded that Guerrero was not “intentionally ignored.” He also cites documentation that jail guards checked on Guerrero throughout the evening. Pointing to Guerrero’s drug history, including a drug test that she failed while pregnant, previous arrests, and her lack of prenatal care before entering the jail, Kerr wrote that Guerrero’s jail delivery was “unfortunate,” but “does not change the fact that [Guerrero] was the person who was ultimately responsible for her having been in jail.”

A family medicine doctor analyzing the case for the company found that the proper emergency plans were in place when Guerrero was incarcerated.

According to a jointly filed summary report of the case, Anderson claims she “never observed Ms. Guerrero’s water break and only found a small amount of discharge that was not blood-tinged, which is not consistent with labor.” She also contends she was present for the delivery.

Rick Bunch, Guerrero’s attorney, says the jail has a pattern of ignoring inmates’ health emergencies. The county “may have a plan and say, ‘We’ll do this’ or ‘We’ll do that,’ but then they don’t, so the result is delay, delay, delay,” he said.

Bunch also said the jail’s overreliance on licensed vocational nurses—a physician visits the jail four hours a week, according to the contract—is a leading reason why emergencies such as Guerrero’s occasionally end in tragedy.

“Well, when you’re pregnant, any moment you can change,” he said. “The nurse shouldn’t second-guess the patient just because she’s an inmate.”

Guerrero’s story may have never come to light if she hadn’t filed a lawsuit. Even the Texas Commission on Jail Standards failed to catch the incident in its annual inspections in 2012 and 2013. Diana Spiller, a research specialist with the agency, told me that inspectors review a random sample of inmates’ medical files, so it’s possible to miss a particular mishap, especially in larger jails.

Outside of the lockups, few know how pregnant women are treated. But for years, Diana Claitor, co-founder and director of the Texas Jail Project, has been trying to get a glimpse inside. Her approach is to work with inmates and families to navigate the system, instructing them on how to file complaints and get help when they need it. In the process, she’s learned a lot about how jails fail pregnant women.

One of the first calls Claitor remembers came in 2007 from a woman whose daughter had miscarried while in jail. She asked Claitor how she could recover the body of her grandchild.

“It was so sad and such a desperate outreach from an older woman who knew of no one to go to,” Claitor said. As word of her organization spread online, she began hearing from more and more women—an outpouring that is reflected in recent data. From 1980 to 2010, the number of incarcerated women in the U.S. quadrupled, from fewer than 50,000 to more than 200,000, according to The Sentencing Project, a Washington, D.C.-based organization that studies criminal justice policy and reform.

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists estimates that 6 to 10 percent of women in correctional facilities are pregnant. Because incarcerated women often struggle with substance abuse or mental illness, they tend to have more complicated, higher-risk pregnancies that require more attention. Medical groups recommend that women receive contraceptive services, pregnancy care and counseling while incarcerated, but research consistently shows gynecological and postpartum services are often inconsistent and inadequate. Poor care often means poor health outcomes for their children.

County jails, much more than state prisons, often house pregnant women. That’s because people who are arrested in Texas usually go directly to a county jail, where they might stay for weeks or months waiting for their case to be heard or awaiting bond. If they arrive pregnant, there’s a decent chance they might have complications or even go into labor while locked up.

When Claitor initially brought a concern about pregnant inmates to the Texas Commission on Jail Standards in 2008, she said, she felt ignored.

“Their response was more or less that that must be a freak incident,” she said. “I was pretty much dismissed.”

At the time, the commission had no idea how many pregnant women were booked in jails. That frustrated Claitor, so she began working on a pair of laws to start gathering data. Along with the ACLU and the Texas Catholic Conference of Bishops, she convinced the Texas Legislature to pass a law in 2009 requiring the commission to track how many pregnant women are booked into county jails each month. The law also required jails to address the medical, mental health, nutritional and housing needs of pregnant inmates in their health services plans, which the commission reviews every five years. A second, related state law passed that same year bans the practice of shackling pregnant women during labor, delivery or recovery, unless a sheriff or correctional officer determines she is a security or flight risk.

Claitor said the reforms were a step in the right direction, but have had limited impact. Neither law requires jails to report whether pregnant women are receiving the care outlined in the health plans. Nor did the 2009 reforms require the commission to come up with detailed best practices; that’s for the jails to determine. County jails aren’t required to report to the commission when or why pregnant women are shackled.

Commission officials acknowledge that the quality of health care is uneven.

“In the end, it’s up to the county as to how they’re going to provide [services],” said Brandon Wood, executive director of the commission. “That means, if they’re going to have to drive someone 60 to 70 miles to provide the care that’s been ordered, or if they have a contract to bring [a doctor] in, that’s fine, as long as they ensure that they’re doing it.”

Often, jails in rural areas aren’t equipped to address chronic health concerns, including pregnancy. Many urban counties, such as Harris, have full medical wards in their jails or access to large county health districts. In contrast, small counties may have a single nurse on site; a physician may be available only once a week.

“When a person is pregnant they have a long list of ongoing needs. Women need to see a doctor routinely, even for a normal pregnancy,” said Brian McGiverin, an attorney with the Texas Civil Rights Project specializing in prisoners’ rights. “There are a multitude of issues, and jails simply are not set up to provide that sort of care. They generally are understaffed and underfunded for the number of inmates that they have, even for simple issues.”

Several formerly incarcerated women I spoke to for this story had a litany of complaints. Prenatal vitamins aren’t always available, and they describe paltry “pregnant snacks” of an extra carton of milk or sandwich. They also reported feeling intimidated or overlooked by jail staff or medical personnel. The women said the sleeping mats were painfully uncomfortable. They or family members on the outside would have to make multiple requests before a thicker mattress was provided, or more food was given, or a doctor was called.

Marta Tingdale, a pediatric nurse in Waxahachie, was one of those persistent parents. Her daughter Amber was 10 to 12 weeks pregnant when she was sent to the Ellis County Jail in 2008. Amber would call her mom as late as 2 a.m. to tell her that she was spotting, but the jail physician and nurses didn’t seem to think anything was wrong, Tingdale said.

“I was trying to calm her down and reassure her that they’re going to take care of her, even though in the back of my mind, I didn’t think they were,” she said.

Tingdale also worried that Amber wasn’t getting enough fruits and vegetables, necessary sources of vitamins for pregnant women and their developing babies. A deficit of vitamins as well as iron and folic acid can lead to low birth weight, affecting bone development and long-term cognitive outcomes.

After seeking help from the Texas Jail Project and calling the sheriff’s office and jail every day, Tingdale was able to ensure that her daughter got better food and more milk and vitamins, but she says the process was daunting and intimidating at times.

“It’s very, very frustrating that you’re not able to intervene in all the ways that you would like to,” she said. “As a family member, you’re concerned about the person, but you’re also concerned about that baby. You’re trying to ensure that that baby is going to be OK once it’s born. It’s very stressful to try and manage that.”

In July 2014, Shela Williams, a 29-year-old Austin mother who struggles with mental illness, was arrested for violating probation and booked in jail when she was 18 weeks into her pregnancy.

Before she landed in Travis County Jail, Williams had visited a specialist, who warned her that her pregnancy was high-risk; her baby, whom she had named Israel, had been diagnosed with spina bifida, a neurological disease. Williams said she informed jail staff of her condition and asked to see a specialist right away, but it was two weeks before she was able to visit one.

Six weeks into her stay in jail, Williams had a routine checkup with a doctor, who discovered that Israel’s heart had stopped. Williams was rushed to the hospital to be induced, where she delivered Israel with the help of a midwife as a jail guard looked on. Israel had died in utero. Williams alleges she was restrained during her delivery, according to a complaint she later filed with the Texas Commission on Jail Standards. Jail authorities allowed her to spend the night with Israel before sending her back to jail, but they denied her request to attend his funeral. Instead, she claims, she was put in lockdown.

“It broke my heart to know that she had to be in there, having the baby by herself, being scared and not knowing what was going on,” said Kellee Coleman, Williams’ friend and an Austin activist who was also incarcerated while pregnant.

When Williams returned to jail, she immediately began experiencing pain, according to her complaint. After requesting multiple times to see a doctor, Williams was sent to the hospital the next day, where a doctor determined she had an infection.

In her complaint, which she filed in February with the help of Coleman, Williams claims she should’ve seen a doctor sooner because of her high-risk pregnancy. She also claimed that jail staff initially ignored her requests for medical attention after her delivery.

After a nearly three-month investigation, the commission concluded, based on a review of jail and medical records, that she received proper care and timely attention while incarcerated. In its conclusion, the commission wrote that investigators, despite multiple attempts, were unable to interview hospital staff or the midwife. Based on a statement from the jail guard who was present, the commission concluded she wasn’t restrained to the bed.

Coleman an activist with Mama Sana/Vibrant Woman, an Austin-based group focused on issues that disproportionately affect women of color, says she plans to respond to the commission’s conclusion on Williams’ behalf.

Williams’ story inspired the group to reignite the movement that the Texas Jail Project and the ACLU started back in 2009. In response to Williams’ and Guerrero’s experiences, the commission formed a committee, which included Mama Sana, the Texas Jail Project, the ACLU and the Sheriffs’ Association of Texas among others, to discuss improving the care and treatment of pregnant women.

Alone in a medical cell, Guerrero knew she couldn’t wait any longer to start pushing.

Activists have an ambitious agenda. They want county jails to treat every pregnancy as high-risk, arguing that the stressful nature of incarceration can adversely affect a pregnancy. They want jails to put in place emergency labor and delivery procedures. They want a ban on placing women in solitary medical observation cells such as the one where Guerrero delivered Myrah. And they argue that information about midwives and doulas should be more readily available in county jails, especially in those that lack prenatal specialists.

Spurred by the committee’s discussions, Wood said he plans to make information about midwives and doulas available to county sheriffs and jail administrators, following Mama Sana’s recommendation. The agency also began collecting data on births: Between January 2014 and May 2015, at least 70 incarcerated women across Texas delivered their babies while in custody. (The commission does not collect data on whether the births occurred in a medical facility or in jail.) Guerrero’s lawsuit also motivated inspectors to review pregnant women’s medical files when evaluating county jails.

Still, the commission won’t go as far as making specific care recommendations, because county resources vary so widely, said Mike Seale, a member of the commission board and medical director of the Harris County Jail. Many people who land in a county jail, especially those who are poor, already struggle to access prenatal care or mental health services, he said.

“We try and stabilize people; it’s a very short-term environment,” Seale said. “In a perfect world we could design a perfect system, but unfortunately it’s an imperfect process. Having dictates or services that don’t take that into account might be an untenable solution.”

Sometimes, Wood says, sheriffs look to alternatives to incarceration, including personal recognizance bonds, to avoid the high cost of prenatal and obstetric care.

The coalition’s efforts also inspired state Rep. Celia Israel (D-Austin) to file a bill in this year’s legislative session requiring county jails to gather more information on the care provided to pregnant inmates, including specific policies such as prenatal vitamin regimens, nutrition plans and calorie counts of food for expectant mothers. The bill, signed by Gov. Greg Abbott in June, also requires counties to report to the Legislature how many births and miscarriages occur annually. (A related bill by Israel would have required sheriffs to report every incident in which a pregnant woman was shackled. Opposed by the Sheriffs’ Association of Texas, it was left to languish in a House committee.)

Claitor called the new law a “game changer.”

“We’re going to find out a lot about what kind of doctors [pregnant women] see, what food they eat, how they’re housed, things we couldn’t find out before,” she said.

Five days after delivering Myrah in jail, Guerrero was released on bond. Between stints in rehab, she turned to a familiar coping mechanism to dull the pain and trauma. Today Guerrero continues to struggle with anxiety and the ramifications of her addiction. She has pending possession and theft charges to deal with. She doesn’t have health insurance and can’t get a driver’s license because of her criminal record.

She is also gripped by the memory of Myrah’s delivery and death.

“I don’t trust [anybody] but my family,” Guerrero said. Fearful of police and other authorities, she’s afraid to run basic errands or go shopping. “I’m always paranoid, I have panic attacks, and my house is my safe place, so I always just stay there.”

When she hears a baby cry, it takes her back to the jail cell where she writhed in pain on the floor for hours. She can still clearly see the blood and fluid on the floor.

Her family has struggled to find her consistent mental health care. Services are expensive, and the local provider is often at capacity. Still, she got married last fall and hopes a stable relationship can help her turn her life around. Guerrero realizes she has a long way to go to recover from her past, but vows to do what she can to make sure no other Texas woman goes through what she did. A hearing for her case is scheduled for March.

“All I know,” she said, “is Myrah didn’t deserve [to die].”