Getting Plucked

How the poultry industry turns contract farmers into modern-day sharecroppers.

How the poultry industry turns contract farmers into modern-day sharecroppers.

by Dave Mann

March 18, 2005

It was Monday morning and Barry Townsend headed to work with a bag lunch and his wife’s .38-caliber revolver. He slid into his red Ford F-350 pickup and began the drive from the Townsends’ farm outside Bryan toward New Waverly, where he worked as a machinist. Cindy hadn’t noticed her gun missing that morning. Before leaving, Barry simply told her, “I’m going to work.”

Barry Townsend was not just a machinist. He and Cindy also raised chickens for the Mississippi-based company Sanderson Farms. They were one of about two dozen families that the company had recruited in a 100-mile radius around Bryan to work as contract growers. The work was hard, and the hours much longer than the Townsends had anticipated. Every year, their expenses increased, and the money they earned was never enough. Their financial situation strained their marriage, and they argued often. Cindy occasionally wept at the thought of the bank foreclosing on their farm. Among the small community of chicken growers, it was no secret that the couple was struggling.

About an hour after Barry Townsend left his farm that morning, January 8, 2001, police responded to reports of gunshots at the Sanderson Farms regional headquarters in Bryan.

Townsend, according to police reports, had requested a meeting with managers Kevin Crook and Larry Ryals. When the three men gathered in a small conference room, Townsend turned to Crook and told him to call Cindy and apologize. Crook was confused. “Barry, we don’t know what you mean,” he said. Townsend immediately became agitated and, cursing, insisted on an apology. Then he pulled the .38. Crook nervously agreed and picked up the phone. But he was too flustered and couldn’t dial the number. “I’ll dial,” Townsend said, moving the two men aside.

He began pushing the wrong buttons and couldn’t get an outside line. “Push that button,” Crook said, gesturing as he moved toward the phone. Townsend was edgy and the movement startled him. He jumped back and shot Crook in the chest, killing him. Then he turned and shot Ryals, who raised his arm in self-defense. The bullet gashed through Ryals’ forearm and lodged in his shoulder; he would be the lone survivor. Barry Townsend put the revolver to his own head and pulled the trigger. He was 46.

After a month-long investigation, police closed the case and told local reporters it was unlikely that anyone would ever know what had caused Townsend to kill one man, wound another, and take his own life. Unofficially, however, a simple explanation coalesced: Townsend had been convicted of child molestation in 1998 for groping Cindy’s oldest daughter. According to conventional wisdom, Barry Townsend was a disturbed felon who, as one police detective told Cindy, “went berserk.” But there’s also a more complicated tale being told in churches, across dining room tables, and on the poultry farms around Bryan—a story of modern-day sharecropping and indentured servants.

Recently the Observer spoke with 11 current and former area growers contracted by Sanderson Farms. Many were fearful of retribution; those still under contract talked only on the condition that their names and identifying details not be published. All, however, described the same scenario: The company, working closely with five local banks, requires prospective contractors to obtain loans, often in excess of $400,000, to finance construction of chicken houses. Contractors put up their farms as collateral to secure loans. With their land at stake, they are then subject to total company control. They tell of low pay for long hours, intimidation, manipulation of wages, and health problems that some blame on exposure to additives in the chicken feed.

The Observer made five attempts to contact Sanderson Farms for its side of the story. Terry Thompson, the Bryan division manager, refused two interview requests. He stressed that neither he nor anyone in the company would comment. “That’s what I was told to say,” he said. A spokesman at the company’s Laurel, Mississippi, headquarters did not respond to requests for comment.

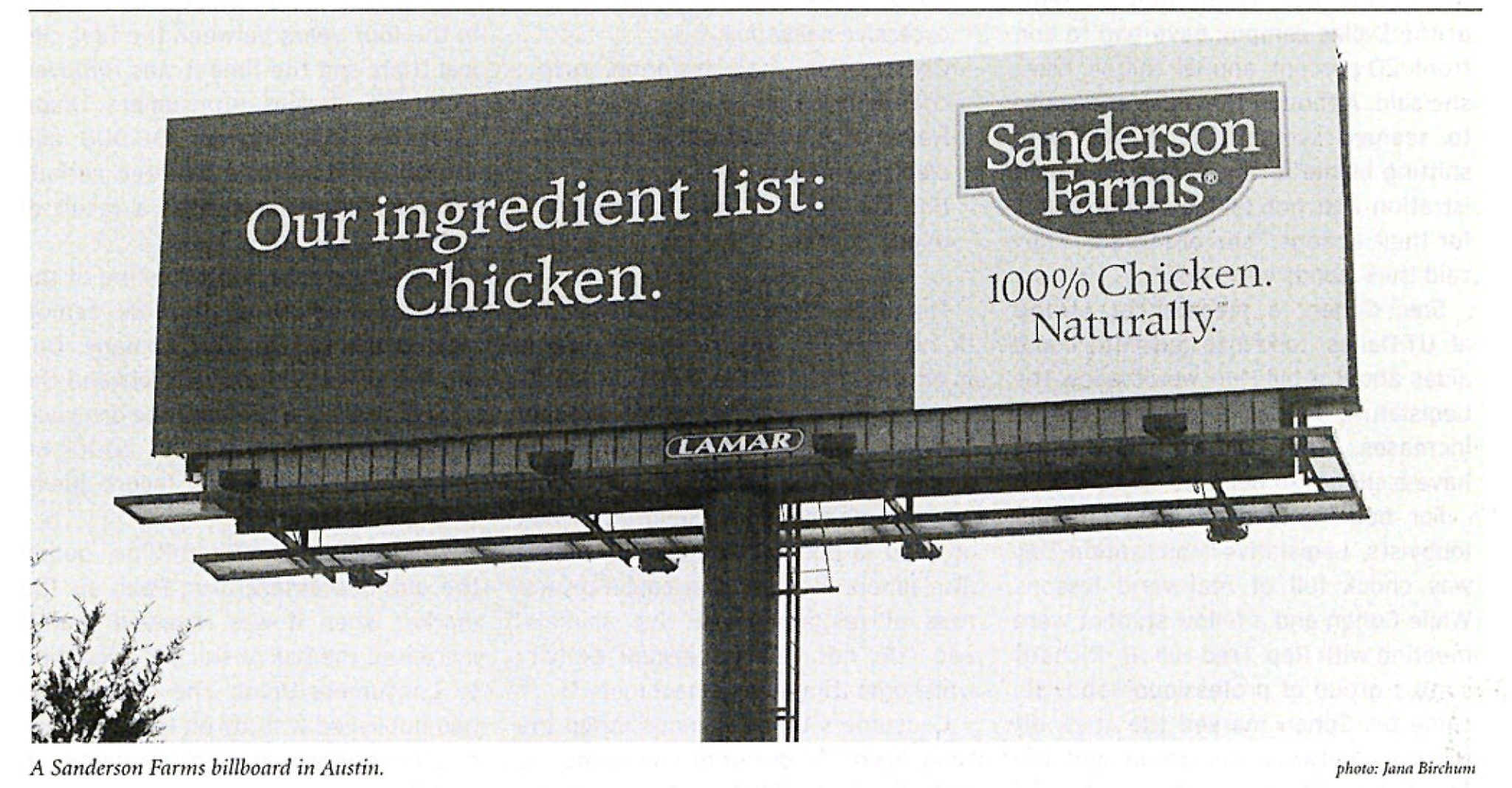

The poultry industry can be a filthy business. The major poultry companies harvest their chickens from industrial farms, lace the feed with growth-inducing hormones, insecticides, and anti-bacterial drugs; some companies inject their meat with phosphates and chicken broth. By contrast, Sanderson Farms presents itself as a family run, health-conscious operation.

Incorporated in 1955, it began as a feed supplier and has since grown into the nation’s fifth-largest chicken producer, a publicly traded corporation that reported sales of more than $1 billion in 2004. It’s still run by the founder’s son, Joe Sanderson, and promotional materials boast that the company has “the foundation of hard work and family values. Today, the ‘family’ includes 8,300 employees and over 600 independent growers.” The company advertises its hormone-free chicken meat as “all natural” and “100 percent chicken. Naturally.” Company billboards declare, “Our ingredient list: chicken.” In 1995, Sanderson Farms expanded its operations into Texas. It built a processing plant and egg hatchery in Bryan and began advertising in East Texas community newspapers to attract growers.

There are three levels of growers in its operation: pullet or hen growers, egg producers, and broiler farms. Pullet growers raise the hens, which the company then collects and delivers to the egg-producing farms. Egg growers cull the eggs, which are hatched in the company’s Bryan hatchery. Those hatchlings are sent to the broiler growers, who raise the chickens that end up in the supermarket meat aisle. All major poultry companies—what one grower labeled the “chicken Mafia”—use contract growers in this way. A few, such as Tyson and Pilgrim’s Pride, own some of their own pullet, egg, and broiler farms in addition to contracting with farmers. According to the industry trade group, the National Chicken Council, contract growers raise 90 percent of the chickens produced in the United States.

The ads that Sanderson Farms placed in local newspapers were emblazoned with testimonials from local farmers who already had contracts with the company. “Now I’ll be able to have a good retirement,” said a man identified as David Boyd of Brushy Creek Farm. In another ad, a farmer contended that the chicken business was “an investment for my children too.”

Nevada and Karen Bedwell, married 35 years, found the advertisements alluring. They liked the idea of owning their own business. Nevada worked as a manager at the supermarket chain HEB, and contracting with Sanderson Farms as egg producers seemed an ideal second income, a job that Karen could do on her own. In 1997, the Bedwells met with company managers. They say that they were given a three-page projection of income and expenses and told that they could expect to gross $121,590 a year, based on a fee of $0.37 per dozen eggs. (Other growers interviewed by the Observer say they received similar documents projecting income and expenses.) Expenses would total $26,700. Sanderson Farms would divert 60 percent of the remaining income to the bank to repay the loan that the Bedwells would have to take out to build the chicken houses. That would leave them with $36,890. Not a bad deal, they figured. Moreover, once they paid off the bank loan—which they say company representatives told them they could do in 12 to 13 years—the egg operation would make the family serious money.

They were given a list of five local banks and loan officers they were permitted to borrow from. The Bedwells selected Farmers State Bank, based in Center, Texas, and began meeting with Greg McCoury, who handled all Sanderson loans for the bank. They wanted to build four chicken barns, two for Nevada and Karen, and two for their daughter and son-in-law. The Bedwells say that McCoury told them that they would need a loan of more than $900,000. Normally, a family of their means—Nevada makes about $50,000 a year at HEB—would never secure that kind of loan. But they had no trouble qualifying because the loan was insured through the Farm Service Agency, a division of the U.S. Department of Agriculture that assists low-income farmers in obtaining agricultural loans. (McCoury did not respond to four phone calls seeking comment.)

After they built the barns to company specifications, the Bedwells say, Sanderson Farms presented them with a contract to sign. They were not pleased with what they read. The contract required them to adhere to farming guidelines that Sanderson Farms established “from time to time” and to strictly follow “all written and oral instructions.” Although the three-page earnings and expense projections indicated that they would be paid $0.37 per dozen eggs, the Bedwells now discovered that the “payment schedule may be amended from time to time” and that Sanderson Farms reserved the right to cancel the contract at any time. If the Bedwells became dissatisfied they couldn’t sue; the contract stated that their only legal recourse was arbitration.

Not only did the contract close the doors to the courthouse, it also made arbitration an unlikely possibility. While court filing fees are relatively inexpensive, registration for arbitration can run as high as $10,000 to $20,000. The Bedwells say they were given one afternoon to accept or reject the contract. At that point, four chicken houses were sitting on their land, and they were responsible for more than $900,000 in debt. They had no choice. “Once they have those houses built, they’ve got you,” says Nevada Bedwell. “They’re in control.”

After their first year as contract chicken growers, the Bedwells were fairly pleased. They had cleared about $30,000. When they talked to Kevin Crook, then still division manager, during their year-end meeting, he told them, “You did well.”

“Yeah, we did good,” Nevada responded. “But just wait till next year, now that we know what we’re doing.” No, Crook said. “You’ll never do that well again.”

The Bedwells were baffled by his comment. But they soon discovered that Crook was right. In subsequent years, their income eroded precipitously. Their expenses were nearly double the $26,700 that the company had initially projected. Propane, used to heat the barns, became increasingly expensive. But the company wouldn’t raise wages to compensate.

Then there were the expenses that nobody had ever bothered to mention, such as the cost of water. Thousands of chickens can consume a lot of water. Despite their hard work, they were losing money by the tens of thousands each year and had to rely on Nevada’s HEB salary just to stay afloat. Their experience was not uncommon. Even the growers who say they’re satisfied with Sanderson Farms, concede that they aren’t making much money. One said he and his wife work all day in the barns, seven days a week and earn about $30,000 total. They had to drop their health insurance. Another detailed how one recent two-month stretch of intense work in the barns yielded $200 net profit.

“This is why they’ve got labor laws to protect people,” Nevada says. “But the labor laws don’t [apply] here because you’re supposed to be a contract worker. They’ve found that gray area outside the labor laws.”

When the Bedwells didn’t comply exactly with Sanderson Farms’ wishes, they would sometimes hear from their loan officer, who, they say, warned them that unless they followed the company’s instructions, they risked losing their contract. “It’s indentured labor,” says another grower. “They’ve basically recreated the sharecropper system,” says Dudley Butler, who represents Mississippi growers in three lawsuits against Sanderson Farms. “We just don’t think that’s fair.”

Nor do Susan and Stephen Martin. In 1998, the Martins marshaled their life savings, retirement accounts and all, to pay $100,000 cash for a 76-acre farm outside the small town of Cameron. Then they used the property as collateral to borrow more than $400,000 from Farmers State Bank to build two of Sanderson Farms’ chicken houses. “We were taken in by [Sanderson Farms’] smooth sales pitch,” Stephen says.

Their egg farm lost tens of thousands of dollars the first two years. By 2000, Susan decided it was time to fight for a raise. She began calling other contract growers and helped organize meetings. The group hatched a plan to collectively lobby Sanderson Farms for a pay increase, but company officials flatly refused to meet with growers as a group. Managers would talk with farmers only individually, and the fledgling organizing efforts collapsed. Eventually, the company offered a raise of $0.02 per dozen. Far too little, thought Susan, who refused to sign in protest.

The Martins were the only growers to refuse. They now believe that the company then identified them as troublemakers and began looking for ways to muscle them off their land and replace them with more pliable growers. They contend that Sanderson Farms technicians and managers were constantly showing up at the farm unannounced, hoping to catch them violating company practices.

On May 7, 2002, the Martins received a letter from then-division manager Randy Pettus on Sanderson Farms’ letterhead, threatening to cancel the Martins’ contract if they continued to lock their barns and didn’t provide the company with a key. The letter was copied to the Martins’ loan officer, Gregg McCoury, at Farmers’ State Bank. The Martins also recall numerous threats to write them up for a “deficiency.” (After three grower deficiencies, Sanderson Farms can cancel the contract and the bank can foreclose on the land.) “Susan and I got on their bad side,” Stephen says. “They wanted us off.”

What really infuriated him, he says, was the way Sanderson Farms managers would show up when they knew Susan would be working alone at the farm. They would surprise her, corner her, try to intimidate her. On one occasion in 2002, a Sanderson Farms technician told Susan that too many of her eggs were underweight and that he might have to give her a deficiency. Fearing that she was about to lose her farm, she began sobbing. After the technician left, Susan couldn’t stop crying. She was having a breakdown. She called Stephen, who rushed home from work to console her.

Nearly three years later, the memory is still painful. “Then I called the doctor,” Susan says, sitting in her living room recalling the incident. She starts to talk about the first time that her doctor prescribed sedatives. She begins to cry and walks into the adjoining study. Then she returns, tissue in hand, and continues. “Stephen got Sharon [their youngest daughter] to come back from college to help me out in the barns,” she says. “I was so knocked out the next few days just because of the medication. And Sharon was afraid that she wouldn’t be able to go back to school.” Her voice breaks and she dabs her eyes. Stephen jumps. “The bottom line is, they care more about their damn birds than they do about the people working for them.”

What ultimately pushed the Martins off their land and out of the chicken business was their deteriorating health. The Martins say that no one in the family had major health problems prior to working in the chicken houses. In the summer of 2000, Susan was diagnosed with cysts on her ovary and intestines that required surgery. She later found another cyst behind her knee and, in February 2002, yet more cysts in her armpit.

Stephen, meanwhile, began to suffer from depression that the family’s doctor later linked to low testosterone levels. Susan suspected that the family’s work in the chicken houses had caused its health troubles. Workers in chicken barns often experience respiratory problems from chicken droppings that disperse into the air. Some of the Martins’ chickens even sprouted cysts and other deformations on their legs.

The Martins’ doctor told Susan to investigate what Sanderson Farms might be putting into its chicken feed. In July 2002, Susan took two samples of chicken feed to Dr. Gerald Kilgore, a veterinarian in Rosebud, Texas. Kilgore sent the feed to Industrial Laboratories in Fort Worth. The tests showed that both feed samples contained fairly high trace levels of arsenic.

In early 2003, Susan found another cyst, this time on her breast. She would never know what was causing her health problems. After undergoing surgery in March, she never went back to the barns. In a letter to Sanderson Farms, her doctor wrote, “Mrs. Martin’s health may be negatively compromised… working in a chicken barn.” The company took over the chicken houses, staffing the farm with its own workers.

Without their poultry income, the Martins’ teetering finances finally collapsed. They attempted to file a lawsuit against Sanderson Farms to save their farm but ran smack into the arbitration clause. Susan wrote the American Arbitration Association, asking for a waiver of the $22,000 registration fee. She received a reply indicating that would not be possible. The Martins concluded that their only option was to declare bankruptcy. “The only way we could get our lives back,” Stephen says, “was to commit financial suicide, which is what we did.” Farmers State Bank promptly foreclosed on the land, and the Martins moved to a house in Cameron, about 10 miles away. Sanderson Farms eventually found another family to take over the barns.

The poultry industry is one of the most highly concentrated and vertically integrated in the United States. It pioneered the use of contract agricultural growers, which has spread to other commodities, from pork to peanuts. As the practice has expanded, there have also been attempts to curb abuses and help contract chicken growers.

Dudley Butler, an attorney in Benton, Mississippi, has filed three lawsuits against Sanderson Farms in the past three years on behalf of growers. In one case, Butler’s client is suing the company for wrongful termination. (His contract was cancelled the day after Christmas 1997.) The company tried to invoke its arbitration clause, which Butler terms “one of the most onerous I’ve ever seen.” A district judge agreed, describing the arbitration clause as “unconscionable” in his ruling against the company. Sanderson Farms has appealed the case to the Mississippi Supreme Court.

Butler’s other two cases are class-actions on behalf of Mississippi growers, who allege that the complex system that Sanderson Farms uses to pay growers is fundamentally unfair. Essentially the company has a fixed pool of wages and employs a ranking system to determine who gets how much money. Farmers are ranked according to who grows the biggest birds (or the most eggs) with the least feed. Farmers at the top of the rankings receive more money; those at the bottom receive less. In court documents the company contends that the system rewards farmers for operating efficiently. Butler says it simply pits one grower against another in a system in which the company calls all the shots.

“We like to call it the gladiator system,” says Laura Klauke of Rural Advancement Foundation International (RAFI-USA), a non-profit based in North Carolina. “The growers are totally dependent on the company in terms of what kind of poultry they get. Who decides who gets what chicks? The company. Who brings the feed? The company. Whose figures do you have to trust because you have no way of verifying them? The company.”

Because so much of what goes into production is controlled by the company, the ranking system then provides Sanderson Farms (and the rest of the “chicken Mafia,” which also relies on the ranking system), a tool with which to manipulate growers’ earnings. The difference between making $20,000 to $30,000—enough to get by—and losing tens of thousands of dollars is simply the quality of the birds and feed that the company delivers.

As one grower explains, you can work as hard as you can, run a farm perfectly, and still lose money if the company sends you poor flocks, and inadequate or insufficient nutritional seed. “You can’t make chicken salad out of chicken shit,” he says. Three states—Georgia, Kansas, and Illinois—have passed legislation to remedy at least some of the problems faced by contract growers.

Butler, along with RAFI-USA and several other farmers’ advocates, hopes that Congress will eventually pass the Fair Contracts for Growers Act, which would protect the right of farmers to sue in the event of a dispute. However, various agribusiness lobbies, including the National Chicken Council, have thus far blocked the bill. Even it were passed, says Klauke, its scope is limited. For contract growers, she concedes, it’s unlikely that there will ever be a “legislative silver bullet.”

It’s impossible to know for sure why Barry Townsend shot two men and took his own life that January morning in 2001. When police interviewed Cindy, she complained that Sanderson Farms had paid them much less than the company had promised. The Townsends felt “like we were being lied to all the time,” she said. She later resumed the use of her maiden name and moved with her children to Indianapolis, where her brother lived. A new family took over the Townsend farm and continues to raise hens for Sanderson Farms.

Among many area growers, there’s little doubt what caused the Townsend shooting. “You can only push a man so far,” says one. After the shooting, Sanderson Farms hired a consultant to conduct an inquiry. The consultant concluded the company wasn’t at fault and that the shooting was an isolated incident, according to news accounts.

Publicly, Sanderson Farms maintained that its treatment of farmers wasn’t the cause. Growers who want to visit the company’s Bryan complex now have to pass through an elaborate security entrance. “It’s only a matter of time until it happens again,” predicts Nevada Bedwell. If the Bedwells hadn’t sold their farm in 2002 and broken free of Sanderson Farms, he says, “I might have shot every one of them. I’d be up in Huntsville prison right now. I don’t want to hurt no one, but if I’d stayed in it, I might have done the same thing [as Barry Townsend].”

None of the growers interviewed for this article expect that conditions will change. Some say they’re especially frustrated because so much of the activism against agribusiness in recent years has focused almost exclusively on whether animals are treated well and slaughtered correctly. Late last year, officials from the supermarket chain Albertsons visited the Sanderson Farms operations in Bryan and a few of the growers’ farms. At the time, Albertsons was negotiating an agreement to stock Sanderson Farms’ chicken in its stores. Officials from the supermarket chain toured Sanderson Farms’ facilities to ensure that the chickens were treated humanely and slaughtered according to specified regulations.

Of the Albertsons visit, one infuriated grower said, “They cared a whole lot about those damn chickens, but they didn’t care about us. And we’re humans.”

IS THERE ARSENIC IN THE CHICKEN?

In advertisements and promotional materials, Sanderson Farms relentlessly pitches its chicken as “all natural.” Susan Martin considers that claim a flight of fantasy. The former Sanderson Farms contract egg grower tested the chicken feed that the company supplied her and discovered trace levels of arsenic.

The heavy metal is number one on the Environmental Protection Agency’s list of dangerous carcinogens. The EPA considers arsenic concentrations above 2 parts per million (ppm) dangerous to human health. Two samples of Susan Martin’s feed, according to lab results, registered arsenic levels of 0.7 ppm and 0.8 ppm, respectively. Some scientists have questioned whether the arsenic in the feed finds its way into the chicken meat that humans consume. The scientific data at this point remains inconclusive.

Sanderson Farms and most other large poultry companies have acknowledged that arsenic exists in their chicken feed. The arsenic is contained in a drug called Roxarsone that most companies add to their feed. The drug, approved by the Food and Drug Administration for use in agriculture, spurs added growth in chickens and also serves as an anti-bacterial agent.

So, does any of that arsenic seep into the chicken meat? The poultry industry maintains it doesn’t. However, Dr. Ellen Silbergeld, a researcher at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore who has studied health problems in the poultry industry, contends that arsenic could pose a threat and says that more research needs to be done. In January 2004, the Department of Agriculture released a study that concluded meat from younger chickens may contain levels of arsenic “higher than previously recognized.”

Silbergeld and other industry critics attacked the government study for underestimating how much arsenic may end up in the chicken that humans eat. Silbergeld pointed out that government researchers sampled arsenic levels only from chicken livers and relied on industry estimates to calculate the arsenic levels in the meat.

Given the dearth of data, the Observer decided to conduct its own test. The Observer submitted five samples of raw chicken meat (four Sanderson Farms chicken breasts and one Tyson thigh), purchased at different supermarkets, to the Veterinary Medical Diagnostic Lab at Texas A&M University. All five samples tested negative for arsenic, at least in concentrations above 0.5 ppm, which is as low as the lab’s machine can detect. The sample was far too small, and arsenic may well lurk in chicken meat in concentrations below 0.5 ppm.

Consumer Reports conducted a similar test recently with a much larger sample and also found no arsenic. Even if it isn’t present in meat, arsenic may pose other hazards. It fouls the environment and could pose a health threat to anyone who lives near clusters of chicken farms. Martin believes that the small level of arsenic in her feed, given to the chickens day after day, created a health threat to her family and the surrounding environment.

Residents in other communities near chicken farms across the country have made similar arguments. In 2003, residents of Prairie Grove, Arkansas, filed suit in state court against six poultry companies (Sanderson Farms wasn’t among them). Prairie Grove residents contend in their suit that use of arsenic at surrounding farms has created cancer clusters in their town. Residents report cancer rates 50 times the national average. No independent studies, however, have been conducted to verify actual cancer rates or the relationship between chicken farms and cancer in Prairie Grove.