2016 Climate Recap: Record Temperatures, Warm Winters and Heavy Showers

Last year was the hottest on record globally. The 10 hottest years on record have all happened since 1998.

President-elect Trump may believe climate change is a hoax, but physics doesn’t care what men think. As humans continue to burn fossil fuels, the Earth’s atmosphere is trapping heat at an alarming rate, throwing its delicate ecosystems off balance.

Over the last decade, we’ve seen evidence of a planet struggling to self-correct. Hurricanes are intensifying, putting millions of people in danger and causing billions of dollars of damage. Large polar ice sheets are melting, leaving animals without healthy habitats and entire islands on the verge of being submerged. And temperatures are continuing to climb.

Last year was no exception. It was the hottest year on record globally, just like 2015 and 2014. In fact, the 10 hottest years on record have all happened since 1998. In Texas, some cities broke temperature records over the summer. Intense rainfall during the spring also left parts of Central and North Texas swamped. Here’s how the state fared weather-wise last year.

A Warm Winter

For Texas, 2016 was the third-warmest year on record, after 2012 and 2011. Houston, Midland and El Paso broke records last year with temperatures 2.7, 3.5 and 2.9 degrees Fahrenheit above average, respectively. Brownsville, Corpus Christi and Lubbock experienced their second-warmest years on record. The highest temperature recorded was 116 F in Falfurrias, a small town south of Corpus Christi in Brooks County, and at least 14 temperature stations in the state recorded temperatures above 110.

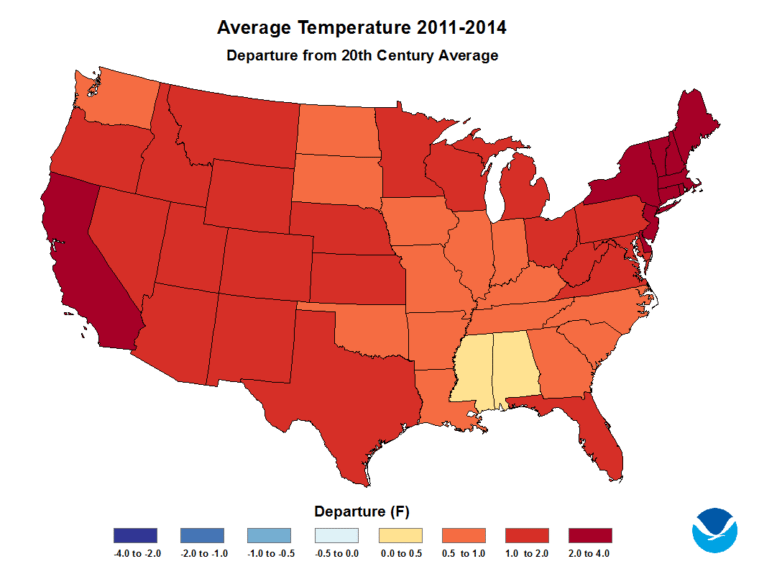

Those figures are in line with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s (NOAA) analysis of temperature data from 2011 to 2014. In Texas, temperatures for the five-year period were one-to-two-degrees warmer than the 20th-century average.

Texans enjoyed a relatively mild summer in 2016, but fall and winter in the state were exceptionally warm. Temperatures in October and November were 5.5 degrees higher than the long-term average. That was despite the fact that 2016 was an El Niño year, which typically brings cooler and wetter weather to Texas. The reason, in part, is climate change. As the Earth warms, the cooling effects of weather patterns like El Niño play a smaller role in regulating temperatures.

“El Niño is conspiring against warmer conditions and you still had the third-warmest year,” said Pedro DiNezio, a research associate at the University of Texas at Austin’s Institute for Geophysics. “Imagine what might happen if you have La Niña and warmer conditions.”

Climate change is playing such a large role in influencing the planet’s temperature that it is overriding El Niño’s effect, DiNezio said. He warned that Texans might experience a scorching summer in 2017 as La Niña, which typically brings warmer weather to Texas, takes hold.

“This year could be the perfect storm,” DiNezio said.

Underwater

As the Earth warms, the atmosphere’s capacity to hold more water vapor increases. As a result, a storm that would have caused a few inches of rainfall is now more likely to trigger flooding. In 2016, Texas experienced at least two intense flood events. In March, flooding along the Sabine River broke the highest river level set more than 130 years ago and inundated the town of Deweyville. Then, about a month later, storms dumped more than 240 billion gallons of water over Houston, leading to the deaths of eight people and damaging about 7,000 homes.

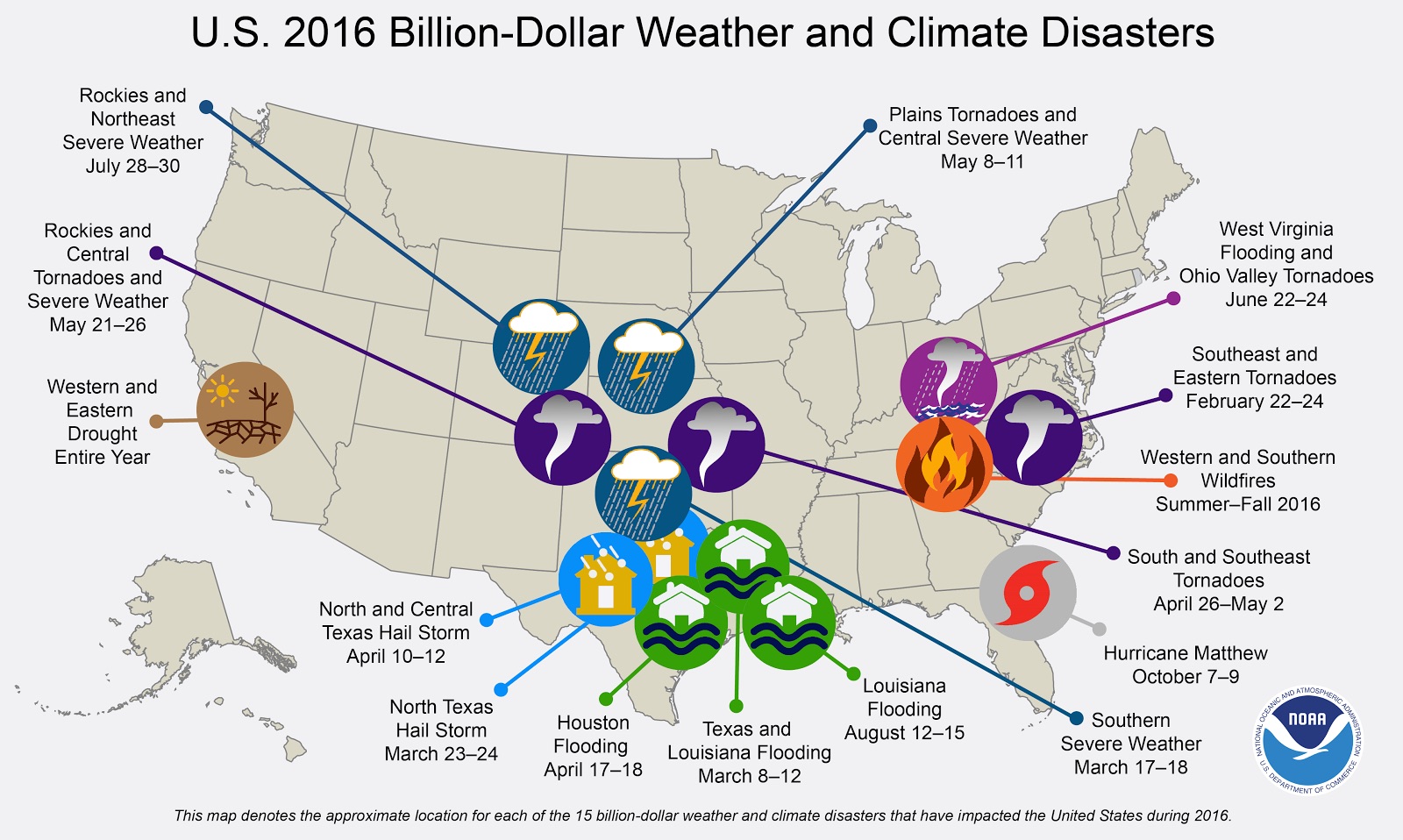

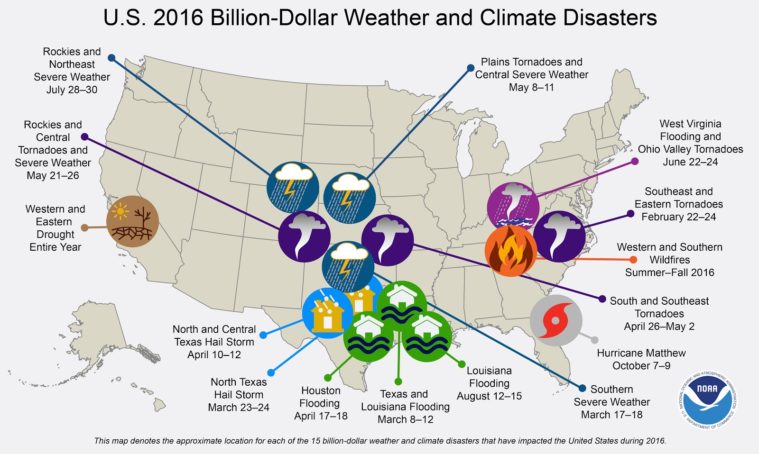

These extreme weather events have an economic and human toll. Of the 15 disaster events nationwide in 2016 that caused losses of more than $1 billion, seven affected Texas. Among them were the flooding in Houston, North and Central Texas hail storms and flooding in the Sabine River basin. NOAA estimates that these events combined caused $10.6 billion in damages.

State climatologist John Nielsen-Gammon cautioned against attributing these specific events to climate change. Attribution science, which attempts to pinpoint the role climate change played in any one extreme weather event, has not confirmed that the Texas floods were worsened by climate change. But Nielsen-Gammon said that his analysis showed the heavy rainfall fit into a pattern of more extreme rain events.

“The odds of flooding have increased,” said Nielsen-Gammon, who has looked at 90 years of rainfall data for Texas. In the second half of that record, the frequency of extreme rainfall events is 20 percent greater than the first half, he said.

That means Texas can expect more downpours in the coming years.