Eminent Disaster

A cabal of politicians and profiteers targets an El Paso barrio

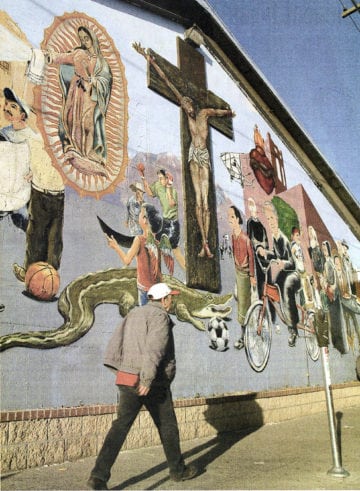

On late Sunday afternoons, when shadows grow long in the Segundo Barrio, the crowds finally begin to thin on El Paso and Stanton streets. Cashiers sit patiently on high stools, watching shoppers navigate seas of brilliantly colored merchandise. After pesos or dollars change hands, the customers pack their last-minute bargains, perhaps a 12-pack of underwear for $3.99, into voluminous plastic bags or suitcases. Then the stragglers head back across the international bridges to Mexico, and the barrio’s streets and alleys are enveloped by a blue dusk, as they have been for more than a century.

Sitting in a U-shaped curve of the Rio Grande, the Segundo is one of the oldest and most important Mexican-American neighborhoods in the United States. During the Mexican Revolution, it was home to spies, plotters, journalists, smugglers, and soldiers of fortune. Francisco Madero, the wealthy hacendado who first called for the revolution, lived for several months at various homes in the barrio while mapping his strategy to defeat Mexico’s longtime ruler, Porfirio DÃaz. Pancho Villa, a guerilla fighter enlisted by Madero, came often to meet arms dealers, to sleep with his wife, to eat ice cream from a dainty bowl at the Elite Confectionary. In a nearby neighborhood, Victoriano Huerta, the drunken dictator who engineered the coup that resulted in Madero’s death, died from cirrhosis of the liver, his bed facing south toward Mexico.

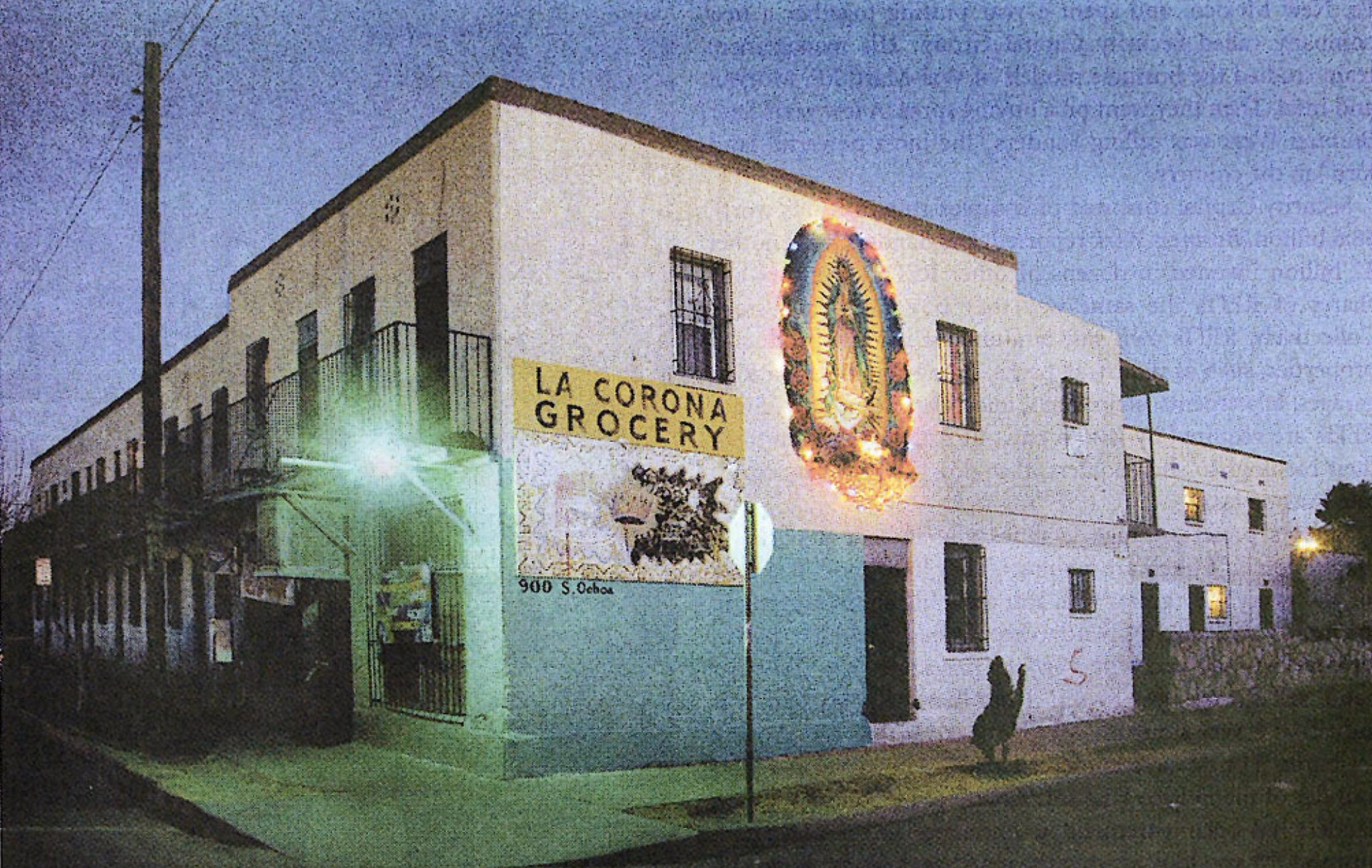

Less widely known, but equally fascinating, historical figures also found comfort and safety in the barrio. Henry Flipper, the first African-American graduate of West Point and one-time informant for A.B. Fall, the corrupt New Mexico senator and key figure in the Teapot Dome scandal, lived in a redbrick building that today houses a notary business. Teresa Urrea, a beautiful woman with miraculous healing powers expelled from Mexico because of her revolutionary activities, lived in the same building decades earlier. And Mariano Azuela, a former Villista doctor, published the first novel of the Mexican Revolution, Los de Abajo, in a building that once housed the printing press for the Spanish-language newspaper, El Paso del Norte.

The barrio, also known as the Second Ward, has been the spiritual home and refuge for hundreds of thousands of people who emigrated from Mexico during turbulent times and fanned out to Los Angeles, Denver, and New York.

It’s a tightly knit community of churches, schools, medical clinics, libraries, stores, and families who have lived and worked there for generations. Through peso devaluations in Mexico and recessions in the United States, the small businesses in the Segundo have managed to survive by catering to customers no one else cares about: low-income Mexicans who walk over to El Paso to shop for the day, and residents of the barrio itself. While other sections of El Paso drop more tax dollars in the city’s coffers, the mom-and-pop shops of Segundo still do roughly half a billion dollars in business a year.

Some of the historic buildings are in need of renovation or repairs. Miraculously, many have escaped the wrecking ball. Now a powerful alliance of wealthy businessmen, aided by local politicians, is on the brink of seizing the barrio. If it’s successful, hundreds of residents will be forced out of their homes. Businesses will be relocated. And the Segundo Barrio and surrounding neighborhoods gradually will be erased-“de-Mexicanized,” some call it-and replaced with an arena, parking garages, condos, lofts, town homes, a “lifestyle retail” district, a “mixed-use” zone, a “mercado,” and an “urban retail” outlet rumored to be a Wal-Mart or Target.

The redevelopment plan was drawn up behind closed doors over two years by the Paso del Norte Group, a civic organization of wealthy oligarchs, industrialists, real estate developers, and politicos from both sides of the border. (Members in the group reportedly must shell out $750 to $1,800 annually and are required to sign confidentiality agreements.)

Under the plan, roughly 325 acres between Interstate 10 and the Mexican border are targeted for redevelopment. Nearly 168 acres probably will be bulldozed, and another 157 acres designated a historical zone eligible for tax incentives. From the rubble, city leaders envision a shining new El Paso that will capitalize on its proximity to Mexico, become a destination spot for tourists, stem the drain of young people, create jobs, produce more affordable housing, and erase once and for all the notion that the city is somehow inferior to its distant cousins in Austin, San Antonio, and even Albuquerque.

The plan calls for a joint effort between the public sector and private investors. The city of El Paso will provide the infrastructure and muscle. Private developers will put up the money, pooling their cash in a financial vehicle called a real estate investment trust, or REIT, that will buy properties.

“El Plan,” as it’s become known, was received with enthusiasm by El Paso’s elected officials, including Mayor John Cook, a songwriter and father of six; City Councilwoman Susie Byrd, a good-government crusader; and 34-year-old Councilman Beto O’Rourke, a boyish-looking, fourth-generation El Pasoan who runs a Web-based technology business.

“Wouldn’t it be fun if there was this neat urban center with lots to do downtown? That’s what we’d like to see for El Paso,” says Kathryn Dodson, the city’s economic development director. “It would be great for El Pasoans to go to a Starbucks downtown.”

The people whose homes and businesses might be razed to make way for latte-drinking Web surfers don’t think the plan’s so neat. Nor do politicians who once called the area home. “This does not pass my smell test. It’s too heavily slanted toward a few wealthy families in El Paso,” says Democratic state Rep. Paul Moreno, who grew up in the barrio. “I don’t want to leave the impression that I don’t want to see El Paso beautified. I just hate for people to come in and try to make El Paso like an Austin or a San Antonio. Our poverty does not permit it.”

Stuart Blaugrund, a Dallas lawyer who grew up in El Paso and represents a group of downtown businessmen, calls the proposed project the “largest land grab” in recent Texas history. The city of El Paso, he maintains, is a willing partner because it refuses to take the threat of eminent domain off the table. “All those stores, which no one in their right mind could say are blighted, are now vulnerable to being expropriated by the government and transferred from one private party-the owner-to another private party-the developer.”

Walter Kim, who heads the Korean Chamber of Commerce and has worked in the area for 25 years, led one of more than a dozen protests and rallies against the plan. “During the peso devaluation, we really struggled and suffered. No one helped us. We had to work hard every day, 365 days a year, 10 hours a day, to make downtown work. Now they love downtown and want to take it away from us. Come on, this is wrong. Right?”

For several years, people in El Paso heard persistent whispers of a plan that would put El Paso on equal footing with world-class cities such as Miami or Chicago. But the plan remained an urban legend until March 31, 2006, when between 500 and 1,000 well-heeled members of the city’s ruling class filed into the renovated Plaza Theatre. There, a group of San Francisco architects unveiled its futuristic vision of downtown, which actually didn’t look much different than scores of other American cities: cybercafes, outdoor restaurants, a modern arena, art exhibitions, tree-shaded sidewalks, verdant parks, and urban hipsters.

The taxpayers who were kept in the dark paid for the bulk of the costs associated with preparing the plan and conducting publicity efforts. (The city of El Paso contributed $250,000; another $260,000 came from a state Economic Development Administration grant, and the remaining $252,000 was put up by the Paso del Norte Group.)

With roughly 350 members, the group is a who’s who of the politically connected. The roster includes mayors, former governors, Gov. Rick Perry appointees, and extremely wealthy businessmen and land developers from El Paso, Juárez, New Mexico, and the state of Chihuahua, according to a list posted on the Web site of Paso del Sur, a group organized to fight the plan. Among the wealthiest are Woody Hunt, a Bush supporter and former member of the University of Texas Board of Regents who presides over a firm that has built more military housing than any other company in the United States; Eloy Vallina Garza, the son of Mexican businessman Eloy Vallina Laguera, whom Mexican sources say is one of the richest men in the state of Chihuahua; and billionaire real estate tycoon Bill Sanders, a hometown boy who has come back to remake El Paso.

Now in his mid-60s, Sanders is the leading proponent of the redevelopment effort. Known as “Billy” by friends, he likes fast cars and off-road vehicles. He is secretive in his business dealings and normally shuns the media. But when the downtown plan was unveiled, he assumed a Bill Gates-like stance at the podium, hand chopping the air, glasses perched on his nose, explaining why it was great for El Paso. (Later, he would tell a reporter, “The biggest failure that I know of in the United States is El Paso.”)

Sanders happens to be the father-in-law of first-term Councilman O’Rourke. To avoid creating a conflict of interest for his son-in-law, Sanders announced he intended to donate any profits he made from the redevelopment to charity. Plan opponents like Blaugrund remain skeptical, saying they haven’t seen the pledge in writing. O’Rourke, meanwhile, has participated in several key council votes, including the critical decision last fall to incorporate the redevelopment project into the city’s comprehensive plan. O’Rourke, who is running for reelection, adamantly denies any conflict of interest despite the fact that his wife, his mother, his father-in-law, and even O’Rourke himself were at one time all members of the PDNG. “My relationship with Bill does not present a conflict, as he cannot profit from this plan, nor can I, nor can any member of my family,” O’Rourke wrote in an e-mail.

By age 10, Bill Sanders was selling Coca-Colas to golfers at the 13th hole of the El Paso Country Club, he once told El Paso Inc., a local weekly. He operated a landscape business while attending El Paso High School. In 1960, he went east to Cornell University, then returned and started buying and selling property. Eventually he moved to Chicago, where he established LaSalle Partners, a real estate and investment management firm. In 1989, he sold his stake in LaSalle for roughly $65 million, moved to Santa Fe, New Mexico, and spent a year putting together a new company called Security Capital Group. His management team studied the business models of Wal-Mart, J.P. Morgan, and Intel. Then they went on a buying spree. A few years later, Business Week was calling Sanders “the most powerful landlord” in the country.

Security Capital consisted of complex ring of REITs worth $8.6 billion, Business Week reported, and Sanders had another $2 billion invested in dozens of other REITs. Investors buy shares of REITs the same way they buy Coca-Cola stock. Collectively, REITs own vast amounts of income-producing properties, such as industrial parks, storage facilities, parking garages, apartments, strip malls, and office complexes. Since REITs are required by law to pay out roughly 95 percent of their earnings to shareholders, they don’t have to pay corporate income taxes.

Sanders prefers storage facilities and industrial parks to luxury hotels. “Hotels are fabulous. They look good. You walk in, and everybody greets you. You are a big shot, but look at the money you have to spend to keep it fresh,” Sanders said in an interview last year with Portfolio magazine. “On the other hand, self-storage, you sweep it out, paint it, and that is it. Industrial is very similar.”

Charles Ponzio, a commercial real estate developer and founder of the El Paso Hispanic Chamber of Commerce, says Sanders has been a tremendous influence in the real estate business. “If you look at what the man has done, it’s huge,” he says. “He was a pioneer in marrying REITs to Wall Street. In layman’s terms, they were able to generate funds from Wall Street to go on acquiring binges, and that’s exactly what they did.”

Unlike other moguls, Sanders was “an oddity,” Business Week wrote. “His name doesn’t even hang on his small office building. There is not a single color photo of him available. He is said to make anyone who works with him-inside the company or out-sign confidentiality agreements.” (Sanders declined the Observer‘s request for an interview. His assistant, Sandra Raudry, wrote in an e-mail, “He is merely one of the many individuals focused on this civic project. The group is hopeful that a very important announcement will be made by the end of this quarter. He believes it should be made professionally and to all the media at one time. Therefore, he will be unable to accommodate an interview at this time.”)

Sanders sold Security Capital to GE Capital Corp. in 2002 for $5.4 billion, according to news reports. Keeping a sprawling ranch in northern New Mexico for vacations, he returned to El Paso and established Verde Corporate Realty Services. The company’s area of operations encompasses a huge swath of land on both sides of the border, stretching from San Diego and Tijuana on the Pacific Coast to Brownsville and Matamoros on the Gulf of Mexico. A globalist who relies on sophisticated, computer-generated marketing information, Sanders believes this binational territory is undervalued and poised to become the manufacturing and distribution center of the world.

“A good friend of mine, who shall remain nameless, said, ‘All these guys never do anything just for philanthropy. There’s always some personal angle.’ That’s just the way it is,” Ponzio says.

Once the El Paso plan was unveiled, Sanders made it clear that a muscular implementation program would be followed. Property owners, he told reporters, would have the choice of exchanging their properties for shares in the REIT, selling at fair-market value, or facing condemnation by the city. “Unfortunately, it may happen that at some point, we’ve got to say, ‘Sorry we weren’t able to work something out,'” he said. Then he added that city officials would have to “begin the process of taking your property at fair-market value.”

Exhorting the City Council to be courageous, Sanders and other core members of PDNG retreated to their office suites to drum up investors for the REIT. Meanwhile, “the revitalization plan from hell,” as retired lawyer Jesús Ochoa puts it, “marched on apace.”

The field marshal tasked for the effort was City Manager Joyce Wilson, a blonde, spiky-haired woman with a master’s degree in public administration from Harvard University. Wilson, who worked for the cities of Richmond, Virginia; Yuma, Arizona; and Arlington, Virginia, is an intimidating figure with far more managerial experience than the five of the eight council members, who are in their mid-30s or younger and newcomers to elected office.

Wilson has her hands full. In a city that is 80 percent Hispanic, charges of economic racism have arisen. And in a city where many people speak two languages, language

has become a potent weapon.

“The status quo losers that live in Segundo are up in fucking arms because their hood is going to go from old and busted to new hotness,” a pro-plan blogger wrote in a screed posted on the Paso del Sur Web site. “Maybe a little kick in the nuts of motivation in the form of tearing their shitholes down will get them to do something with their lives.”

On that same Web site, O’Rourke, whose council district includes the Segundo Barrio, has been called a “little puto,” a “punk-ass bitch,” a liar, a thief, and a sellout. Business and government elites have been labeled as “neo-conquistadors.” Wilson has been characterized as an “anti-Mexican scold.” In conversations elsewhere, defenders of the barrio have been tagged as “nostalgists,” “sentimentalists,” and “blight preservationists.”

One document the city’s Hispanic community found most offensive was the GlassBeach study, a $100,000, city-funded research effort aimed at rebranding El Paso. Riddled with typos and grammatical errors, the consultants compared present-day El Paso to a Chevy truck (“old, reliable, dirty, not exciting”) and suggested the new El Paso should be an Infiniti SUV (“new, reliable, practical, style/exciting, not pretentious.”)

In their report, the consultants included a picture of an old cowboy. Next to him were the words, “male, 50-60 years old, gritty, dirty, lazy, speak Spanish and uneducated.” The photo was juxtaposed against images of Penelope Cruz and Matthew McConaughey, suggesting the wealthy and beautiful couples who would live in the new El Paso.

Language has also been used to redefine the areas targeted for redevelopment and to spread propaganda. Suddenly, the U-shaped shopping district that includes El Paso and Stanton streets is the “golden horseshoe,” and the Segundo Barrio, which has never been considered “downtown,” is part of downtown.

Concerned by the way the plan was being perceived, City Manager Wilson dashed off a hurried memo to a PDNG leader, outlining a counterattack that included figuring out ways to engage and neutralize the losers, disseminating graphic photos of blighted buildings, and attempting to recast the debate in more favorable terms. “Provide photos of conditions and make it graphic,” she suggested. “Again, focus on the new vision but desanitize it so we don’t get into the chain stores taking out the locals.” She also advised that the proposed convention center-arena be “downplayed” because it was “probably the lightning rod for tax increases for folks.”

Wilson’s propaganda may have worked on people who live away from downtown, but those who live and work there weren’t fooled. “They keep showing buildings that are infested with rats and cockroaches. How come they don’t show the nice buildings? That’s what gets me mad,” says Martha Cruz, who owns the little apartment building where Henry Flipper and Teresa Urrea once lived. Her office is whitewashed and cool, with a small bed tucked in the corner for a grandchild. Cruz rents out apartments for $260 to $375. Small and clean, they bear little resemblance to the “slums” and “Calcutta Hiltons” that an El Paso Times editorial writer called housing in the barrio. In fact, the apartments could be worth a lot of money. Cruz says an investor recently offered her mother $1.5 million for a family-owned store a couple of blocks away.

City officials are quick to point out that the shops along El Paso and Stanton streets won’t be touched and may actually have more customers when the plan is implemented. But with big-box stores poised to come in, shopkeepers know it’s only a matter of time before they’ll go the way of the dinosaurs. “The first time I saw the plan, I thought it looked nice,” says Son D. Smith, who operates a lingerie shop. “But we’re going to lose when the big companies come in.”

In December 2006, the city took another giant step toward implementing the plan, passing an ordinance declaring that 188.42 acres in the redevelopment district are “unproductive, underdeveloped, or blighted,” and making them part of a tax increment reinvestment zone, or TIRZ. Within this zone are 40 houses, 10 duplexes or triplexes, 48 apartment buildings, 254 commercial properties, and three industrial properties. Overseeing the TIRZ will be a 15-member board that will review the proposed projects.

A couple of weeks later, Sanders and six other businessmen formed a REIT called the Borderplex Community Trust. Investors who had a net worth of more than $1 million or incomes of at least $200,000 were invited to join. (Ted Houghton, a member of PDNG and a Perry appointee to the Texas Transportation Commission, says he was invited to invest, but declined.)

It didn’t take long for the Borderplex REIT to raise $30 million. In a move that was highly symbolic, one of the REIT’s first purchases was the 18-story Chase Bank Building, one of the tallest buildings in downtown El Paso. Sanders’ real estate firm, Verde Realty, has offices there.

Asked recently who some of the investors were, Wilson says, “Well, I mean, some of the private sector businesses who have approached us are in confidential negotiations, and so I am certainly not going to disclose that right now.”

Demands Blaugrund: “Why would that be confidential? That’s a perfect example of the city knowing information and refusing to disclose it to its citizens.” Blaugrund and others are frustrated by all the unanswered questions, including how much the plan is going to cost taxpayers. “How can you not know a year into the plan how much it’s going to cost?”

It’s still not clear which buildings are going to be rehabbed and which demolished. Under the original plan, for example, the Centro de los Trabajadores AgrÃcolas Fronterizos, an 8,000-square-foot building sandwiched between the two international bridges that provides services to farmworkers, was scheduled to be demolished and replaced with a parking lot and big-box store such as Wal-Mart or Target. After Carlos Marentes, the center’s executive director, made it clear he wanted nothing to do with the plan, City Councilwoman Susie Byrd said the center wouldn’t be destroyed. But Mayor John Cook said the center still could be razed. “The commitment I made to them is that if it makes more sense to put a parking lot where your building is, we’ll have to build you another one that’s bigger and better,” Cook said.

It’s also not clear how the city is going to cope with all of the displaced persons. One city document shows that $3.6 million has been budgeted for the “relocation of residents,” or about what the city plans to spend on engineers and consultants. As a consequence, a lot of neighbors have quit making home improvements, skipping the coat of paint they had planned to put on the bedroom, forgoing the new water heater or swamp cooler.

Byrd says the plan calls for 3,000 new downtown housing units, 30 percent of them affordable. “The coolest part is this: You will have a downtown El Paso after implementation where there will be more opportunity for lower- and moderate-income families to live than there is today, and it will be quality housing.”

Like the other council members and the mayor, Byrd says she’s opposed to using eminent domain to get rid of viable businesses so the chain stores can move in. Yet she won’t take eminent domain off the table. “Blight is a gut reaction,” she adds. “I represent neighborhoods where the property owners are so irresponsible and so negligent that it contributes to the decline of the whole neighborhood. I’m not going to let those folks drive the agenda for downtown.”

Blaugrund says the threat of eminent domain weakens property owners’ ability to negotiate fair prices. “What the government is doing is forcing the sale of private property from one person to another. It’s not using eminent domain in the traditional sense for a highway, a hospital, or a school,” he says. “Here, they’re forcing people to sell properties under duress or have it taken away in a condemnation action.”

The city hasn’t used eminent domain yet, but it’s about to turn up the heat. One tool the city could use, Cook said recently, is to report all property offers to the appraisal district. “I don’t have to use eminent domain,” the mayor says. “All I have to do is take the offer down to the Central Appraisal District and allow the property to be taxed at its real market value.”

The city’s also going to start sending zoning and building inspectors into the redevelopment area to inform owners of code requirements. “If necessary, police and fire departments will assist in explaining and enforcing violations,” a city document stated.

Wilson says the inspections aren’t meant to pressure owners. But she does admit the inspections were related to the redevelopment plan. “Part of the implementation strategy is to start code enforcement in conjunction with the investments taking place,” she says.

Though the bulldozers haven’t appeared yet, many of the most fervent opponents of the redevelopment plan feel it’s just a matter of time until the Segundo Barrio slips into history alongside its inhabitants and occasional guests-the lovely Teresita Urrea, the fierce military chieftain Pancho Villa, and Francisco Madero, who barely could see over a horse’s withers, but remains a towering figure in both Mexican and American history.

“I’m not one who expects to get something for nothing,” muses longtime resident Charles Ponzio. “But I hope what El Paso gets is more than just taking out the local players for corporate America.”