How pesticides poisoned South Mission, but no one is responsible.

*

by Jesse Bogan

June 29, 2007

The pesticide mixer’s wife limped out of the early morning darkness onto a white bus bound for the state Capitol. Tomasa Garza, 72, settled in next to her husband, her gray hair pulled back, a large gold cross dangling from her neck. In Spanish, she asked a relative across the aisle about his family. He said a child was ill and they were unsure why. It’s a familiar refrain for the 20 passengers on the bus and for the hundreds more from their poor neighborhood in Mission, Texas, near the Mexico border. For decades this community has been plagued by cancer and birth defects, a trail of human suffering that residents are convinced stems from the pesticide-processing plant that operated in the neighborhood from 1950 to 1972. Since the facility closed, attempts to remove toxic residues and compensate residents have repeatedly foundered.

As the bus set forth at 5:30 a.m. on May 2, residents hoped this time would be different. They were traveling to Austin to ask lawmakers for a resolution encouraging the Texas Supreme Court to decide a case that has languished since 1999. The mass toxic tort is against Hayes-Sammons Chemical Co. and a slew of other big firms affiliated with the processing facility and a large warehouse a half-mile away. Federal and state environmental agencies have found significant contamination at both sites, but a jury has yet to hear arguments in the case while the court works through legal technicalities. In the meantime, plaintiffs have died waiting for the trial.

Ginger Bourbois Silva, 53, organized the bus trip to fulfill a deathbed promise to her father. A longtime laborer at the plant, he died at 69, plagued by kidney, lung, and heart failure and cirrhosis of the liver. Three relatives who worked with him died in their 40s. “Dad told me before he died, ‘I want you to keep fighting for this case,'” Bourbois said. “He told me, ‘I am not going to live long enough to see it come to an end.'”

For Tomasa Garza, the 650-mile trip was her first to Austin. Her husband David, 75, happily went to work for Hayes-Sammons in the ’50s when they were newlyweds with a newborn; when he left the company 10 years later, they had seven children.

“It smelled like the devil,” he recalled.

Work began at the facility before the horrors of the organochlorine pesticides handled there-DDT, BHC, dieldrin, toxaphene, aldrin, and chlordane, to name a few-were fully known. Most of these pesticides were eventually banned in the United States as potential carcinogens recognized as particularly lethal for their long, persistent effects on the environment, including accumulation in animal and human tissues.

Garza has never been a smoker, but his doctor has told him his lungs look like he’d smoked tobacco for 40 years. He blames working at the plant. But it is difficult and expensive to prove the cause and effect, and that’s part of the reason for the length of the struggle in Mission.

Still dark, the bus pressed north past McAllen and Edinburg. Past flat citrus groves, produce rows, and sorghum fields that helped define the Rio Grande Valley.

Garza’s wife closed her eyes, but her lips moved in prayer until she fell asleep in her window seat. Up a few rows, Eliza Bourbois, Ginger’s 74-year-old aunt, in a royal blue, satin blouse with her lips coated bright red, gulped down a fistful of pills, chasing it with a breakfast taco and bottled water. She has had a kidney and her spleen removed. One of her four children can neither hear nor speak.

Though much of the farmland skewered by U.S. 83 in South Texas has vanished beneath asphalt, the area’s agricultural legacy is still celebrated every year with the 75-year old Texas Citrus Fiesta. Mission, once in the heart of the grapefruit groves, has doubled in population during the past 15 years, to 60,146 people. Long ruled by an Anglo royalty, the peasants of the kingdom were segregated in South Mission, a neighborhood divided from the rest of town by a strip of railroad tracks.

South Mission is Mexico with a Texas license plate. The Rio Grande and Frontera Tamaulipas are 4 miles away. There are still plenty of grown-ups who remember swimming in irrigation canals as kids before the public pool was desegregated. Rows of tattered, wood-frame houses cram together, some with barren yards piled with old furniture, busied by children.

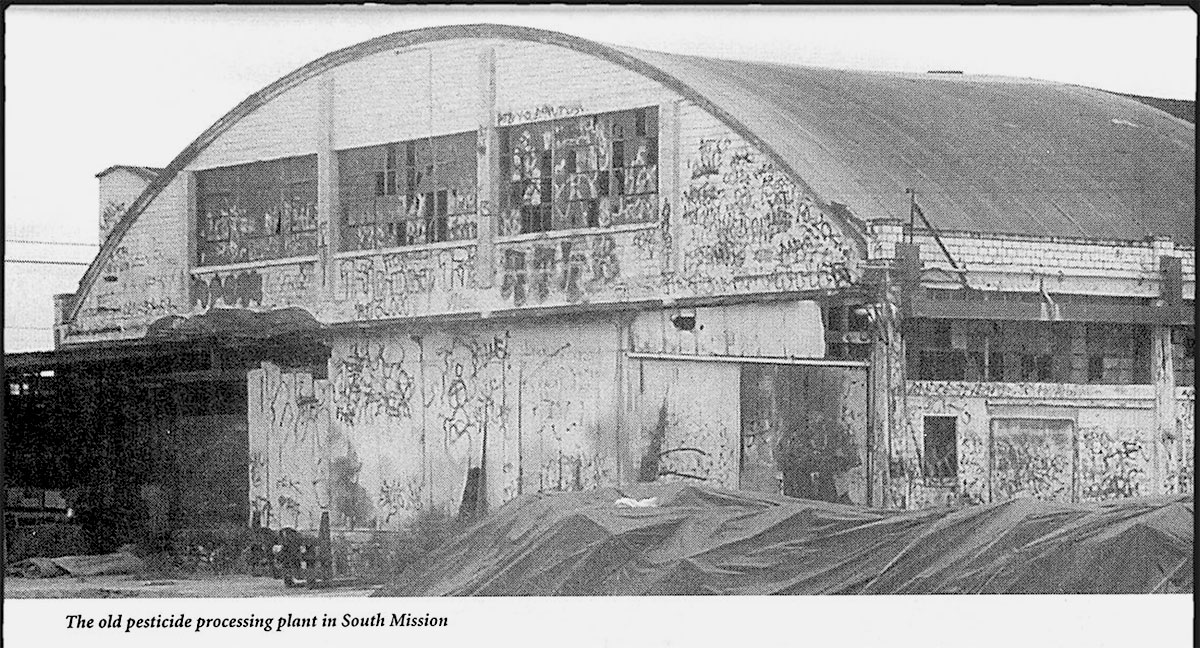

Across the street from the first row of houses is a building with a large exhaust fan mounted at the top, anchored in rust and decay. The aqua blue structure resembles an airplane hangar with broken windows and scrawled graffiti. Pigeons fly through large holes in the roof, which has sprouted weeds. In its heyday, the facility and its warehouse were one of the largest pesticide processors in the region.

The plant exhaled pesticide dust like a vacuum cleaner with a full bag. The fan sucked poisonous dust and fumes from the factory, sending them into the neighborhood. Families left their windows open most of the year because they didn’t have air conditioners. Strong Gulf winds moved the dust around so much that residents said they could taste it. The poison blew off of trucks, open-top kettles, and piles of residue left outside, which neighborhood kids used like a community sandbox, according to former workers, locals and court records. Rainbow colored storm water frequently flooded unpaved streets, at times muddying dirt kitchen floors.

Jose B. Rodriguez, 85 and a native of Zacatecas, Mexico, was a young man when he came to Texas in search of a new life. He settled in South Mission back before running water, back when it was “puro rancho, puro caballo, puro buro,” Rodriguez said from the front porch of the house he’s lived in for decades. In 1950, Hayes-Sammons expanded from a local hardware store, turning a juice plant near Rodriguez into the pesticide production facility. It was like a car factory moving into the small neighborhood. Happy to have a good-paying alternative to the fields, workers lined up to be hired during peak seasons.

“We put our hands in the poison,” said Rodriguez, who welcomed the work so he could support his family. “The people were ignorant, only knew to work-to work. It was the best. We all fought to work there. We didn’t know it was dangerous, but in time we knew because people started to get sick.”

Inside the facility the fans and forklifts, which had mufflers that kicked up dust, created a constant din, former workers said. Material arrived by truck and rail, sometimes packaged in 50-pound bags, 55-gallon barrels, or 200- to 300-pound cardboard drums. It came in powder, liquid, and wax, which was quartered with an axe and tossed into the kettle. Laborers had respirators, aprons, goggles, and gloves, but the attire was cumbersome, and whether to don it was each worker’s decision. Either way, it was still impossible to beat the dust, which workers said sometimes burned like chili powder in their eyes.

In the early years, a skin-rash outbreak spawned an inquiry by Shell, a supplier of dieldrin. The pesticide, a substitute for DDT, was used on citrus, cotton, and corn. Suspected of causing cancer and birth defects, it was banned for most uses by 1987, according to the Environmental Protection Agency. The Observer obtained a copy of Shell’s inquiry from 1952, titled “Investigation of Dermatitis Cases-Southern Texas-Mission, McAllen, Harlingen Area,” from a lawyer for the plaintiffs. The report blames the outbreak on “ineffective dust controls combined with poor housekeeping practices and careless handling of the materials.” The Shell report said dieldrin was safe at other plants when “normal, reasonable, precautions are observed,” but at Hayes-Sammons, workers wore short-sleeve shirts with the top buttons undone, and the facility was awash with pesticide dust.

“From the appearance of some of the clothing it was very evident the men had been wearing the same clothing day after day,” according to the report. “There was no evidence of gloves being worn … the lockers are in an open corner of the warehouse. As a result there is dust on the lockers, benches and the floor … sufficient insecticide dust had settled out of the air and had been tracked in to combine with water on the floor of the shower and toilet area to make mud. … There were no regulations regarding cleaning up before smoking or eating. Numerous employees were noticed smoking with their hands white with insecticide.”

The report recommended coveralls and a clean washing facility. Workers were to be sent to a doctor immediately when a rash occurred “rather than continuing to work until the rash has spread to other parts of the body.” The report said that “some of the trouble can be attributed to the type of workers employed at this plant. Due to language difficulties and other factors, an efficient employee education and training program is difficult to establish and maintain.” The report’s author optimistically concluded that a new level of knowledge may have been reached: “Possibly there is much more latitude in the amount of exposure to dieldrin formulations that can be tolerated by humans without immediate serious result than was anticipated previous to this time [emphasis in original].”

David Garza recalled that only the hearty, the ones who could tolerate the nausea, stayed on. “We had one man in there at the time go into convulsions,” he said.

That man was Jose Rodriguez, whose journey from Zacatecas didn’t turn out exactly as he had imagined. He was pouring phosdrin, a potent liquid, into jugs, and the fumes made him drop to the factory floor “like a chicken,” Rodriguez said. Briefly hospitalized, he didn’t return to work. Garza said the plant supervisor came out on such occasions and warned them to be careful. “How could you?” Garza asked. “You had to work with what you had.”

The supervisor was Cyril Weber. Now 94, rail thin with a slight hunched back. A friendly and old-fashioned Nebraska native, he said in an interview at his home outside of Mission that Garza was “kind of a know-it-all” because he could actually understand directions. Others, Weber said sarcastically, could be told one minute to do something, and the next they’d be eating the poison by the spoonful.

Weber’s short-term memory is poor, but his sense of history is rich. A machinist by trade, he said he built the “poison plant” in South Mission, which he estimated employed about 100 people during peak seasons.

“Some jobs, they were ticklish jobs, they was awful dangerous,” Weber said. “We never was too careful about who we put in there. For a while there we didn’t know it was very dangerous.” Later on, management realized “some of that stuff was really hard on your liver.” Still, Weber is skeptical of the lawsuits, describing plaintiffs as opportunists claiming they were seriously injured. He was adamant that handling the product “like gold dust,” along with good hygiene and common sense, was sufficient, even though that didn’t always happen.

“The only people who got injured by it were the people who were reckless,” he said. That included his young, adventuresome nephews who visited the plant one day, played in a lift, and ran around getting dirty. The next morning they were vomiting, he said. He speculated that they became ill because they didn’t bathe after visiting the plant.

The plant operated in an agricultural boom time, and his boss, the late Clay Brazeal, always demanded bigger profits, Weber said. So Hayes-Sammons bought formulating plants and warehouses in Yazoo City, Mississippi, to be closer to cotton fields there, as well as in Raymondville, another Rio Grande Valley town. The company also built a facility across the border in Reynosa. “When he made a dime, he’d want to make 20 cents,” Weber said of Brazeal. “It was the way he was, like all the bankers. They are all the same breed.” Better safety measures, like kettle lids and a fence around the plant, could have been installed, he said, but such extras were unacceptable deductions from the bottom line.

As a manager, Weber said he didn’t have constant contact with the materials and that some employees struggled to understand directions. He said one part of the operation he considered particularly careless was the handling of BHC, a suspected carcinogen that sometimes was trucked to the plant in uncovered dump trucks. It was typically piled on a concrete slab outside, where today the Mission Independent School District maintenance and operations offices are. He said “little eddies” of dust would form. On windy days, it blew off the site toward Pearson Elementary School a block and a half away.

Mark Deckhard, now 48, ran around the property as a child. Early last spring, he took a break from playing catch in the street with three of his four kids to describe what it was like back then. He has lived in the same small house most of his life. A few years ago, a crew working with the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality dug out his entire front yard because it was contaminated.

“We used to hide in the containers,” he said. “Nobody said, ‘Hey, don’t hide in that. It’s poison.'” In recent years Deckhard, who can see part of the facility from his yard, said he was diagnosed with leukemia, which went into remission after chemotherapy. He spoke in a matter-of-fact tone about the risk to his children as they hugged and hung on him.

“I know he’s going to get it,” Deckhard said of his son Forrest, 12, who stood beside him on the porch.

“I am definitely going to get it, right Daddy?” the boy asked proudly.

By 1961, some residents didn’t think the facility was such a boon. That year Frances Garza (no relation to David and Tomasa) typed out an eloquent plea for help to the city of Mission, complaining that “even a mentally healthy person would be driven insane” by the constant grinding and pollution from Hayes-Sammons. The poison dust fouled clothes on the line and the inside of her home so badly that it deterred visitors, the letter said. “It is impossible to live and breathe insecticide dust daily,” Garza wrote. “I am sure this company does not like to be complained about, but this is a residential area.”

It wasn’t until 1972 that the plant, now owned by Helena Chemical Co., abandoned the site and moved 14 miles east on U.S. 83 to the rural, less congested outskirts of tiny Alamo, where it operates today as a distributor of packaged products. The late Frank Dusek, a private landowner from the area, bought the old formulating plant property after it closed and used it for heavy-equipment storage and other endeavors. Pesticide mixing was over, but the Gulf wind continued to blow strong, and residents played and walked around the old factory. In 1980 Victor Viner, a young environmental engineer for the EPA based in Houston, showed up to take samples. It was the onset of the cleanup effort that more than a quarter of a century later has yet to be completed.

Viner, now 55, recalled by telephone from Florida his first impression on seeing kids horsing around barefoot in yards without much vegetation. “It was poor, and it was just sad-the idea that you have a manufacturing company in the middle of a neighborhood, a manufacturing plant of some of these long-life pesticides.”

He said he can’t believe the struggle to clean up the facility continues 27 years after he left.

Viner sampled soil at the plant and surrounding yards, as well as sediment in a reservoir that abutted the nearby municipal water treatment plant. The results, apart from the water sample, would alarm regulators. There was a full buffet of organochlorine pesticides, either banned or soon to be banned, at levels way above EPA standards. The highest DDT onsite sample exceeded federal standards “by over hundreds of thousands of times,” according to court records. Samples of lindane, dieldrin, toxaphene, and chlordane were also off the charts. The situation in South Mission was exacerbated by the fact that the pesticides were more dangerous when mixed together, according to government documents.

Later in 1980, the EPA sued Dusek-who claimed in court records he didn’t know the history of the land he bought-for injunctive relief. Also named were former owners Tex-Ag Co., which had purchased the site from Hayes Sammons and Helena, which had bought it from Tex-Ag. It was “required as the result of an imminent and substantial endangerment to health, and the environment,” according to the complaint filed at the federal courthouse in Brownsville. The lawsuit stated the public, including children, entered the facility freely. It alleged “dangerous concentrations of pesticides and related chemicals are being released from the property at issue, being blown through the air into the surrounding area, which area contains homes, elementary schools, and a school bus depot.”

The Texas Department of Health launched a study of the neighborhood residents and school district employees in the area. But the blood samples showed they were exposed only to “a mild to moderate degree of environmental contamination” and “there does not seem to be any demonstrable elevation of their serum pesticide levels or any substantial evidence that there have been any adverse health effects which can be epidemiologically linked to their exposure to the Plant Site,” according to a copy of a 1981 interoffice report. One caveat the report mentioned was that “much still remains unknown about the long-term effect of pesticides on man and on the environment.” The “potential” for harm was not ruled out.

The author of the report, Richard Beauchamp, senior medical toxicologist for the Texas Department of State Health Services, told the Observer that he stood by his conclusions.

The federal case ended in 1983 with a consent decree approving a court-ordered cleanup paid for by Helena and Tex-Ag. Crews dug up contaminated dirt from neighboring yards and from the plant site and buried it on the property. Then the repository was topped with caliche and an asphalt cap. Dusek, the landowner, was directed to maintain the cap.

According to the decree, the companies were protected against further civil litigation “except for actions for injunctive relief relating to disposal or migration of contaminants from the Dusek site which EPA did not know about and which it could not have reasonably known about.”

Looking back, Dallas-based Samuel Coleman, director of the EPA Superfund program for Texas and several other states, said in an interview that the cleanup method was not a good choice.

“Typically you wouldn’t put a landfill in the middle of a neighborhood,” he said. “Unfortunately, what happened in the ’80s, the common wisdom was that pesticides and other things deteriorated over a fairly short period of time. … So typically, as had been done for many years, the way you disposed of chemicals was you buried it in the ground. And the thought was that they would naturally deteriorate. Well, we now know that they do not.”

As time went on, the asphalt cap fell into disrepair, as did the old storage warehouse a half mile away in an overgrown field.

By 1987, so much pesticide had seeped through wooden floors of the warehouse that it became one of the first 10 sites on Texas’ new Superfund registry, where it remains today. Ironically, attempts to clean up the mess, often done without consulting the community, helped spur legal action. Residents complained that cleanup crews showed up unannounced in full body protective suits. No-trespassing signs warned residents to stay out of an area where people commonly hung out and sat on an old loading dock, or crossed on foot to get groceries at HEB. As streets were blocked and tons of dirt hauled away, residents wondered if it had anything to do with cancer and illnesses that seemed to plague the neighborhood. By 1998-27 years after the plant closed-about 2,400 people from the area had organized and started filing lawsuits, which soon merged into one.

The mass toxic tort lawsuit was filed in Hidalgo County against 33 parties, including the former owners, transporters, suppliers, and a who’s who of chemical firms, including Chevron Chemical Co., Dow Chemical Co., E.I. du Pont de Nemours Co., Monsanto Co., Montrose Chemical Corporation of California, Kerr-McGee Chemical LLC, Shell Oil Co., and Union Carbide Corp. The plaintiffs allege negligence; emotional distress; failure to warn the public about potential health risks in or close to the facilities in Mission; that the operation caused at least 225 instances of cancer and 44 cases of liver disease, among other illnesses; and depreciated the value of homes, according to the petition and a plaintiff’s attorney.

Defendants denied the main accusations, according to court records.

A judge winnowed the case down to about 1,600 plaintiffs, mainly former workers and nearby residents, but the file continues to grow. The voluminous stack of medical reports, interrogatories, petitions, answers, and death certificates comprises so much paperwork the Hidalgo County district clerk’s office uses a medley of carts to wheel the case file around.

Helena, Union Pacific Railroad Co., and Rohm and Haas Co. made undisclosed settlements with many of the plaintiffs, sometimes for payments of as little as $200, with $2,000 in the upper range, residents said. Attorney fees, attorney expenses, and the large number of plaintiffs brought down the settlements. In some instances, attorneys made more money per plaintiff than residents still living with the dirt. Some recipients of the money welcomed it, while others were indignant.

Ester Salinas, 52, the most vocal of the community activists involved in South Mission, blamed lead plaintiff attorney Ramon Garcia, who also is a former Hidalgo County judge, for the paltry settlements. “[He] sells us out,” she said. “What the hell is $300 going to get you? A lot of people feel cheated. They don’t know who to believe anymore. … I want the companies to admit guilt. … They forget about the real human suffering. How could they settle out for such little monies?”

Garcia said the frustration is being improperly directed because the companies that settled were involved mainly with remediation efforts and weren’t the alleged polluters. Helena, he said, only owned the site a few years.

“It’s not little money when your responsibility is very minor compared to others,” he said. “I understand. I mean, shit, people are upset. Lawyers are upset.” He added that he often gets call from plaintiffs who are ill. “Many of them are just living day by day.”

Houston-based Linda Laurent Thomas, another plaintiff attorney, said “hundreds of thousands of dollars” has already been spent on the lawsuit.

“We can’t give them their health back. The only thing they can do is get some monetary compensation,” Thomas said from her Thomas & Wan, LLP office in Montrose, where an entire wall is covered with files from the case. Further proceedings were stalled after defendants appealed to the Texas Supreme Court in 2004 regarding questions about five plaintiffs with non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma being tried together. Thomas said she believes the cases will likely have to be tried one plaintiff at a time. “It’s going to be a long process,” Thomas said. “How are we ever going to get justice for these people?”

Despite attempts by the EPA and TCEQ, there has never been a widely accepted effort to clean up the full extent of the contamination in South Mission. Some residents believe the only way to do it properly would be to remove several feet of soil, and then trash the homes, dirt, and roads in an incinerator. The cost would be so prohibitive it would likely take an act of Congress to fund it.

TCEQ and EPA have spent millions in the area of the old Hayes-Sammons warehouse and processing plant, partly for soil removal, work that costs as much as $60,000 for every yard cleared. The sums for remediation rivaled the total worth of some of the impoverished homes, patched like coops with plywood. Other yards have been left alone, the house structures untouched, leading some residents to believe there is still contamination lingering in attics, under the pavement, and in odd spots and crawl spaces.

Meanwhile, uncertainty dogs residents who worry that a suspicious lump or growth might form in their bodies in the future. It’s tough to know, because the danger is not like a hot stove that immediately burns. It’s more like cigarettes. A few years of use might not harm you, but a lifetime of lung darts most likely will-though not always. Everybody’s immune system is different, and some people were around it more than others. Because it’s chronic, not acute, and typically stays in body fat for years without detection, many assumptions must be made to assess blame for leukemia, a gimpy extremity, or non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Meanwhile, the producers of the poison are largely shielded by the burden of proof, the impossibility of absolutes in the science. In the case of South Mission, there are so many previous owners of the abandoned plant that blame is washed out. All that’s left are the agencies tasked with assessing and cleaning up the mess.

“Complaining to the EPA that you are ill is not going to get you well,” said Samuel Coleman of the EPA in an interview after a particularly contentious community meeting. “I can only reduce the exposures; we are not a medical [agency). I take what they say at face value, but I have no authority.”

After intervention by U.S. Rep. Lloyd Doggett, an Austin Democrat who briefly represented the area after the contentious 2003 redistricting, the EPA eventually assessed the property again. It identified “significant concentrations” of pesticides on the southern half of the old formulating plant, including beneath the decrepit asphalt cap and shed floors. Of 128 soil samples, 35 tested above the industrial standard for organochlorine pesticide. Taking into account the public access to the property, the EPA determined in 2006 that the site was a “threat to public health,” and a $6 million cleanup was budgeted. The EPA is seeking repayment from “four potentially responsible parties” – current owner Johnny Hinojosa, Dusek Trust, Tex-Ag Co., and Helena. The agency hasn’t ruled out other possible polluters.

To the dismay of resident activists, the cleanup was approved to an industrial standard, not residential. It focused on the area of the old cap and the toxic landfill underneath it. Though elevated samples came from under the foundation of the processing plant with the silent, large fan, the decaying edifice wasn’t to be touched because of private property rights, officials said. (In the end, the owner agreed to let authorities dismantle the structure.)

The community braced for another cleanup. The EPA set up dust monitors at various points in the community to keep tabs on levels. Lunch recess was canceled for the rest of the school year at Pearson Elementary because “we just wanted to prevent concerns of any extra exposure,” said Principal Leticia Gonzalez.

Expecting to dig down 3 to 4 feet, cleanup crews discovered the contamination went deeper. In one 10-by-10 foot section, they followed elevated soil samples down to 19 feet and stopped because they reached the water table, said EPA onsite coordinator Valmichael Leos. He said crews didn’t sample the water in that area because the goal of the project was just to remove contaminated soil. One of four monitoring wells sampled for pesticides showed elevated pesticide levels. South Mission residents have long received water from the city, which has a treatment plant in the area. The shallow groundwater in the region is not drinkable. City water comes from the Rio Grande.

The digging also turned up “surprises,” Leos said. Workers found an underground storage tank and a concrete sump. The sump had sludge inside that reeked of pesticides. Leos wasn’t sure what the sump was for. “According to the consent decree (from 1983) we are not supposed to be finding those surprises,” Leos said. “We would be interested to know if there is anything else buried that could potentially be harmful.”

Just outside Austin, Ginger Bourbois made her way through the aisle, chatting with riders, who sometimes laughed with excitement.

The bus disgorged its passengers beside the state archives on the Capitol complex, near the phrase etched on its side about how “all political power is inherent in the people.” The Garzas slowly walked across the Capitol grounds. “Let’s go see if we can talk to Gov. Perry,” Tomasa Garza said, lagging behind while her husband reflected on pushing through Austin decades ago during cotton season. Their local state representative, Democrat Kino Flores from Mission, joined them for a prayer outside. “How long is it going to take to right a wrong?” Flores asked before departing for the House floor.

The group packed into an elevator and went up a floor, then walked out onto the balcony overlooking the cavernous House chamber. They squeezed into a section of chairs beside a group of high school students. Ginger Bourbois waited with anticipation. Finally, legislators would use their power to goad the Supreme Court to send the case back to a courtroom in Hidalgo County.

Just before noon, Flores stepped to the dais. He stood before half his colleagues on the floor amid the subtle buzz of floor chatter. Scattered onlookers peered from the balcony.

He spoke so quickly the group wasn’t sure if he had started the presentation, or rather had just finished a 30 second introduction. But he didn’t come back up to the dais, and the small group from Mission was frozen in disbelief and disappointment. Few had managed to catch what he had said. Slowly, sheepishly, the group rose and made for the exit. At least two people were on the edge of tears, including Bourbois.

The chance to get the powerful to listen to their sad story ended up being a brief, impersonal mention for the record. House Resolution 1844 was to be reviewed by a committee, which is where it died at the end of the legislative session.

Gathering herself, Bourbois tried to put a positive spin on the experience. “It is a minor setback, you know, but we were recognized, we were recognized, and the effort was here. That’s the good thing,” she told the group.

Soon Flores joined them in a lobby. Asked if he thought his colleagues were aware of the environmental struggles in his district regarding the old plant, he said, “Of course not. They don’t have a clue; they don’t have an idea because generally until it affects their districts they really don’t start caring.” Asked if he thought the brief floor time was sufficient to inform other lawmakers about the challenges, he said he didn’t need to go on and on, that it was just a matter of making it official.

On June 15, the Texas Supreme Court ruled on the case, allowing it to go back to Hidalgo County eight years after it was filed. But the breakthrough came with a stern opinion demanding that plaintiffs in mass toxic tort cases thoroughly link alleged adverse health affects to specific chemicals long enough before trial so that defendants have a “reasonable opportunity to prepare.” It appeared to be yet another hurdle, perhaps an insurmountable one, for the folks from Mission.

Jesse Bogan is a freelance journalist and former border reporter for the San Antonio Express-News.