Big, Bland John

How a dull exterior masks one of the most conservative records in the U.S. Senate

Democratic strategists in Texas have been telling anyone who will listen for the past year that they can defeat John Cornyn, the state’s junior U.S. senator, in November. This is big talk for a party that hasn’t won a statewide race since 1994 and hasn’t held Cornyn’s senate seat in 47 years. But they have some fancy polling data to back it up. More than a third of Texans wouldn’t know their junior senator if he fell on them. They call this “name ID” (or lack thereof) in the political consulting business. Cornyn’s is abysmal for a politician who’s served as a Texas Supreme Court justice, state attorney general, and, for the past six years, U.S. senator. Of those who do know Cornyn, fewer than 50 percent view him favorably—dangerous territory for an incumbent seeking re-election. Some of those same polls show him running closely with Democratic opponent Rick Noriega.

But you don’t need polling data to know that Cornyn can be beaten. Just watch him give a speech. “Dull” is an understatement.

When Cornyn spoke at the Republican state convention on June 13, for instance, the excitement level—even among the 5,000 ardent Republicans assembled in a downtown Houston convention center—resembled a chamber music recital more than a rock concert. They offered Cornyn polite applause, but nothing near the standing ovations for the state’s senior senator, Kay Bailey Hutchison, or for former presidential candidate Mike Huckabee.

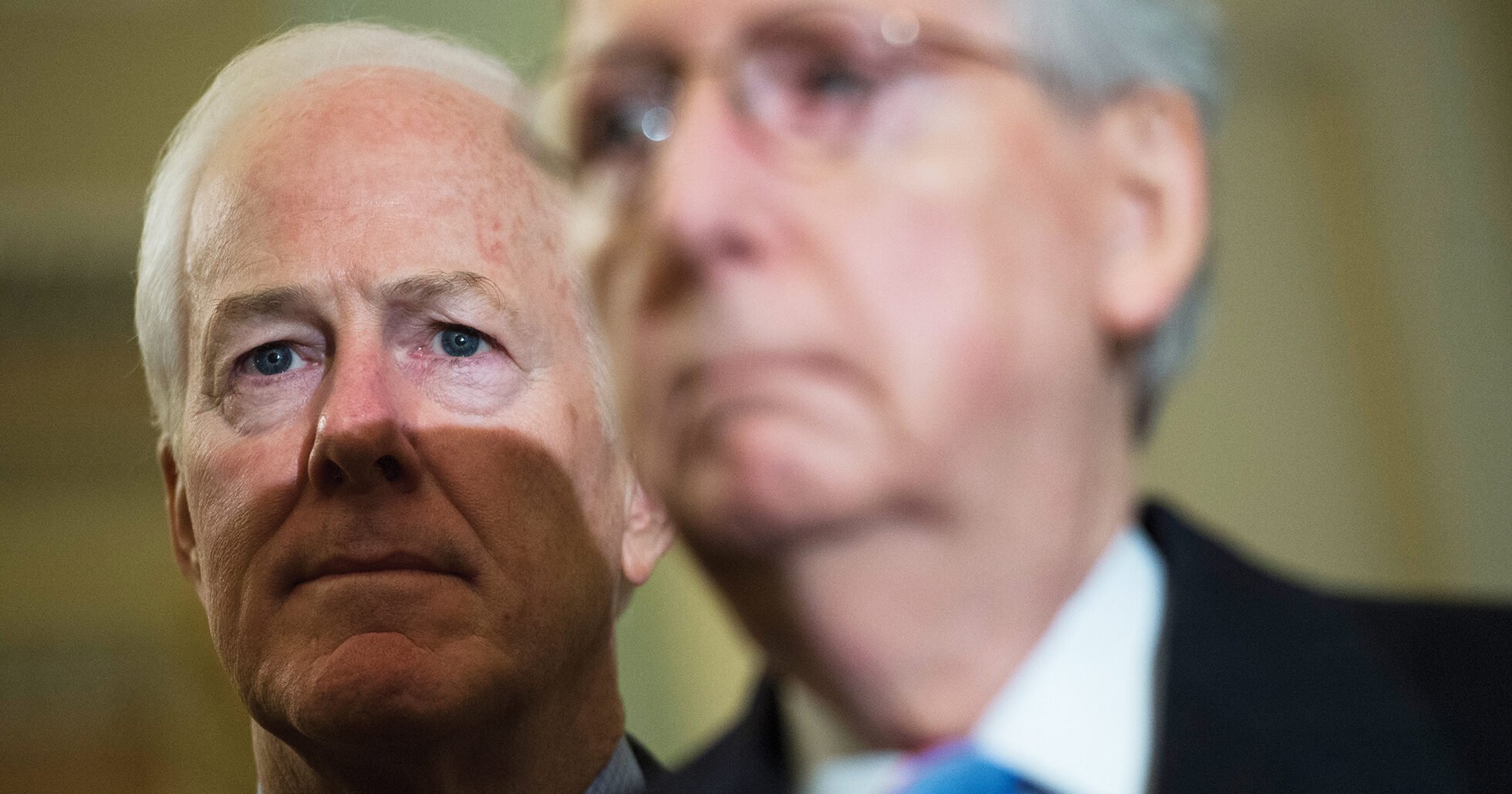

Cornyn looks like a senator: He’s tall and lanky, with wispy white hair over the kind of broad, distinguished face that makes him look deliberative all the time. He’s also blessed with the bearing and charisma of a tax attorney. He doesn’t connect with audiences; he talks at them. In Houston in June, his deadpan delivery rendered the convention speech instantly forgettable.

The most memorable moment of Cornyn’s convention appearance was the “Big John” video that introduced him — an over-the-top spoof showing the lawyerly Cornyn in cowboy attire on a horse. A Jimmy Dean imitator crooned in the background about the exploits of Big John: “He rose to the top in just one term, kept Texas in power, made lesser states squirm—big John … big, bad John.” Cornyn looked ridiculous, an irony given that he actually spent a lot of time on a ranch as a child and regularly hunts and rides horses. Nonetheless, the video was universally mocked in newspapers and blogs, and, predictably, on the Daily Show.

Cornyn seemed to sense the ridicule to come. “I hope you got a smile out of that video,” he told the crowd. “My staff convinced me it would be a good idea. Maybe I need a new staff.” It was his best line of the day. He immediately turned once more to stone. “It was an attempt to bring a little humor to a subject I take very seriously.” He went on to detail his record in the Senate. Perhaps his speech deserved more attention. The record he must defend is so conservative that few Texas political observers—many of whom viewed Cornyn as a Republican moderate during his time in state government—would have foreseen it six years ago. With his bland style and senatorial looks, Cornyn doesn’t strike you as a right-wing ideologue. His record suggests just that.

“My policy on the war on terror is similar to Ronald Reagan: We win, they lose,” Cornyn told the assembled GOP faithful. (Indeed, he has voted consistently in the Senate to cede power to the executive branch. He voted to strip terrorism detainees of their habeas corpus rights and against congressional oversight of the OM terrorist detention facilities. He backed the president’s secret wiretapping program and once remarked, in a debate over the PATRIOT Act, “None of your civil liberties matter much after you’re dead.”)

“I have protected the sanctity of human life,” Cornyn told the crowd. (He voted to strip funding from abortion and family planning services, and against increased access to birth control.) “I’ve opposed immoral experimentation done in the name of science.” (He’s opposed federal funding for stem cell research.)

“I have supported judges who respect the Constitution.” (He backed the nominations of both Supreme Court justices Samuel Alito and John Roberts, and a host of controversial judicial nominees, including Texas’ own Priscilla Owen.)

“I have supported the traditional family.” (He was a main proponent of a constitutional amendment banning gay marriage.)

When he finished, Cornyn didn’t linger on stage to bask in the crowd’s muted applause. He offered two quick, perfunctory waves to the crowd and ducked backstage.

One major aspect of Cornyn’s first term in the Senate that he didn’t mention: George W. Bush. No one has done more to propel Cornyn’s career than Bush. In turn, Cornyn has offered near complete fealty to the president. No other U.S. senator has voted so reliably with the White House in the past six years.

Now that Bush is one of the most unpopular presidents in American history, Cornyn is trying to distance himself. Even in Texas, Bush polls below 50 percent. Add to that a dissatisfied electorate—polls show about 80 percent of Americans say the country is on the “wrong track.” The historic candidacy of Barack Obama has energized Democrats, who seem poised to make big gains in Congress. This would seem a disastrous year for an incumbent senator who doesn’t excite even members of his own party.

Yet the Democrats seem wholly unprepared to take advantage. Republicans still hold an edge in Texas, and Cornyn has raised nearly 10 times more campaign money than his Democratic opponent. Despite his blandness and a record that borders on too conservative even for Texas, Cornyn may sneak into a second term.

–

When Cornyn joined the Senate as part of a new Republican majority in 2003, it seemed an ideal political environment for him, and not just because he looked the part. Cornyn’s record in state office seemed a good fit for the upper chamber, which bills itself as the world’s most deliberative body. In Texas, he had crafted a record of moderation, at least compared with some fellow Republicans.

“He was an articulate, intelligent judge,” says John Coppedge, an East Texas physician and longtime player in Texas Republican politics. Coppedge has known Cornyn nearly 20 years—they met in 1989, when the future senator was a district judge in San Antonio. Support from doctors has been a key component of Cornyn’s political career. Coppedge has supported and raised funds for Cornyn in every election since, beginning with the successful 1990 campaign for the Texas Supreme Court, though the two have occasionally had their differences. “Politically, it’s fair to characterize him as conservative,” Coppedge says. “But his judicial philosophy was to not legislate from the bench. … Whatever your personal opinion is or whatever you think public policy should be, that’s not your job there. There are some people who have been judges who didn’t quite get over the fact that they weren’t legislators anymore. I don’t think that was John’s reputation.”

Cornyn’s break into statewide politics came courtesy of a Democrat. He was recruited to run for the Texas Supreme Court not by Bush or Karl Rove, but by Democratic consultant George Shipley, then working for the Texas Medical Association, who saw Cornyn as a pro-business moderate who would balance a court then dominated by trial lawyers.

Indeed, Cornyn brought moderation to a divided court that was transitioning from a Democratic majority backed by trial lawyers to a GOP-controlled court that often sides with big business and doctors. In 1995, he cast the deciding vote and authored the majority opinion in a 5-4 ruling that upheld the state’s so-called Robin Hood school finance system, through which rich districts supplement poorer ones. Texas conservatives, who have tried to overturn the system for years, were livid. (Cornyn refused several interview requests for this story.)

Cornyn was elected attorney general in 1998, by which time he was a client of Rove. It was the beginning of Cornyn’s close relationship with Bush, who, always quick with a nickname, dubbed him Corndog. As AG, Cornyn wasn’t overly partisan. A journalism major in college, he was a fierce advocate for he beefed up the child-support collection division—the kind of non-ideological work that earned him a reputation for relative Moderation.

Bush personally recruited Cornyn to run for the Senate seat being vacated by Phil Gramm. Cornyn’s central campaign plank in 2002 was that he would go to Washington to serve on the “president’s team.” A year after the attacks of September 11, he embraced a president whose immense popularity in Texas carried Cornyn into office. It was the best of times for Republicans, who would capture the U.S. Senate, enlarge their U.S. House majority, and take control of the Texas Legislature.

Since arriving in the Senate, Cornyn has supported Bush more consistently than has anyone else. He voted with the White House 96 percent of the time during his first four years in the Senate, according to Congressional Quarterly. In 2007, his support of Bush fell all the way to 90 percent. He’s backed the president on every major vote concerning the war in Iraq. In 2004, he used his seat on the Armed Services Committee to try to block an investigation of abuse at Abu Ghraib. In 2005, Cornyn was one of just nine senators, all Republicans, who stood with the White House and voted against Sen. John McCain’s amendment to ban cruel and inhumane treatment of terrorism suspects. The anti-torture amendment passed 90-9.

Cornyn’s loyalty to the president has paid of His close ties to the White House have boosted Cornyn quickly through the Senate ranks. He serves as deputy whip—the fifth-ranking member in the Senate Republican caucus—an impressive standing for a freshman. The caucus often dispatches Cornyn to speak publicly for Senate Republicans. Though he lacks the charisma to connect with audiences, Cornyn is skilled at breaking down complex policy issues into digestible analogies and talking points. “He’s well regarded in Republican circles for his ability to articulate an argument, particularly on television,” says Jonathan Allen, a political reporter with Congressional Quarterly. “He’s someone who gets media, and that has helped his career. When your colleagues see you doing that, they want to promote you!”

Cornyn has also ascended to an influential position on the Senate Judiciary Committee. From this perch, the former attorney and judge has backed every Bush judicial appointment, including Roberts, Alito, Owen, and Harriet Miers’ disastrous Supreme Court nomination. On Judiciary, he has relentlessly pushed the right wing’s socially conservative agenda. Cornyn is a main proponent of amending the Constitution to ban flag burning and same-sex marriage. (In 2004, Cornyn planned to deliver a speech to the Heritage Foundation in which, according the transcript, he would say, “It does not affect your life very much if your neighbor marries a box turtle. But that does not mean that it’s right. … Now you must raise your children up in a world where that union of man and box turtle is on the same legal footing as man and wife.” He removed the passage before the speech, according to news accounts.)

On April 4, 2005, Cornyn took to the Senate floor to speak about another favorite topic of the right wing at the time: the influence of “activist” judges. It would bring him the most unwelcome attention of his Senate career. “I don’t know if there is a cause-and-effect connection, but we have seen some recent episodes of courthouse violence in this country,” he told his colleagues. “I wonder whether there may be some connection between the perception in some quarters on some occasions where judges are making political decisions yet are unaccountable to the public, that it builds up and builds up and builds up to the point where some people engage in—engage in violence.” He quickly retracted the statement, but the public uproar had already begun. Several newspapers called for his resignation.

As it turns out, this faux pas was committed in service to the party. Senate Republican leaders had asked Cornyn that day to hold the floor as long as he could to prevent Democrats from taking the microphone. After he finished his prepared remarks, Cornyn continued speaking off the cuff until he inserted loafer in mouth.

–

Many Texas political observers have a hard time reconciling the politician they knew in Texas with the ideologue Cornyn has become in Washington.

“There’s really been two John Cornyns over his career,” says a Texas health care lobbyist who’s dealt with Cornyn and asked not to be quoted by name. “He’s really changed his political and philosophical outlook on governing. He is being led and advised by a group of people that would rather have him taking votes that are divisive. In his heart, I don’t think that’s who he is, but that’s certainly who he has become. He’s always been a moderate, or at least until he got elected. I don’t think he had those [conservative] ideologies ingrained in him until he went up to D.C.”

Coppedge posits another theory. He says Cornyn’s views haven’t changed. He attributes Cornyn’s conservative Senate record to the difference between legislating and presiding as a judge. “What he might write in a decision on the [Texas] Supreme Court may be very different than what he would do legislatively,” Coppedge says. In other words, he believes Cornyn hasn’t become any more conservative; his role has changed from objective arbiter of the law to partisan legislator.

Whatever the cause, Cornyn often votes with a small group of two-dozen arch-conservatives in the Senate, and in opposition to the more moderate, and more popular, Hutchison. In July 2005, for example, he was one of 26 senators to vote against an amendment requiring gunmakers to install child safety locks on their weapons. In exchange for protecting children, gunmakers received immunity from lawsuits. Hutchison and McCain backed the proposal.

“He’s very much seen as a partisan Republican,” says Allen of Congressional Quarterly. “There are a fairly limited number of issues where he’s reached across the aisle.”

He also has surrendered to political expediency. In 2006 and 2007, Congress nearly self-immolated over immigration ahead of the midterm elections. Cornyn made clear he opposed construction of a border fence. He told reporters at the time that walling off the entire border was a 20th century answer to a 21st century problem, that the wall wouldn’t stem illegal immigration, and that it was too expensive. “I’m not sure that’s the best use of that money,” he told reporters in early October 2006.

Three weeks later, he voted for the Secure Fence Act—a vote he later described as symbolic support of border security. He said he didn’t think the fence would ever receive funding. (The funding, of course, did come through, and construction began this summer.) His vote for the wall has infuriated some mayors along the border who are fighting the federal government’s efforts to build the fence.

Still, Cornyn has aided South Texas with enough federal projects to earn endorsements from a handful of Democratic politicians in the Rio Grande Valley, including the mayors of McAllen, Harlingen, Pharr, and Mission. (“I am a Democrat, but I cannot say no to Sen. Cornyn because he has been good to us,” Pharr Mayor Polo Palacios told the Rio Grande Guardian after endorsing Cornyn in May.) Cornyn’s Democratic opponent — state Rep. Rick Noriega—is sure to make the border wall an issue for Latino voters this fall.

After Democrats claimed a Senate majority in 2007, Cornyn became even more isolated within the cluster of ultraconservative Republicans. He initially opposed a bill implementing reforms in the intelligence community recommended by the 9-11 Commission. He was one of just 14 Republicans to vote against a reform bill that increased regulations on lawmakers’ interactions with lobbyists.

With Democrats in charge, Cornyn also rediscovered fiscal conservatism. In the fall of 2007 alone, he voted against funding bills for the departments of Commerce, Justice, Labor, Education, and Health and Human Services—in the belief that the Democratic majority was spending too much money. Only a handful of the Senate’s most conservative members joined him in this crusade. Cornyn even opposed a $1 billion package for federal bridge repairs—a vote taken less than two months after the 2007 bridge collapse in Minneapolis (32 other senators opposed the bill).

None of those positions is as potentially threatening to Cornyn’s re-election as his three votes against renewing the Children’s Health Insurance Program in fall 2007. CHIP provides health insurance for kids of working families and is an immensely popular and effective government program. Democrats sought to expand the program to families making as much as four times the federal poverty limit. Cornyn—once again sticking by the White House—wanted a lower income ceiling. Cornyn said at the time that expanding CHIP to cover so many middle-class kids was a step toward “socialized Medicine.”

More than two-thirds of the Senate, including Hutchison, voted for the CHIP bill on three occasions, only to see it vetoed by the president. (The bill remains stalled because the House cannot muster enough votes to override a veto.) Asked about the CHIP votes, Cornyn campaign spokesman Kevin McLaughlin says, “The fact of the matter is, he supported the expansion of SCHIP. He just didn’t support it to the level that Rick Noriega did.” Noriega, a fiveterm state representative from Houston, was heavily involved in the CHIP battles in the Legislature and will no doubt hammer Cornyn this fall for opposing health care for kids.

As election day nears, Cornyn has belatedly distanced himself from the White House and tacked toward the center. He reversed himself to support a beefed-up G.I. Bill in June after withering criticism from Noriega that Cornyn wasn’t supporting Veterans.

A few weeks later, Cornyn got into trouble again by blindly following the White House and had to make some quick reversals. Initially, he voted with the president and against a Medicare bill that would have temporarily saved doctors from a 10-percent cut in their Medicare reimbursement rates. The bill failed by one vote.

Cornyn claimed he voted against the bill because he wanted a permanent fix for Medicare’s broken payment system instead of a short-term patch that only delays the cut. But there was an ideological reason, too. The bill diverted a small amount of money from Medicare Advantage, a program in which insurance companies serve as middlemen to help deliver Medicare payments. It’s a darling of the ideological right and a boon to the insurance industry. Bush said he opposed the Medicare bill mostly because it removed money from Medicare Advantage. Cornyn decided to stand with the president rather than doctors who had supported his campaigns for years, some of whom had donated thousands to his re-election effort.

The resulting furor was intense. The Noriega campaign began spinning out press releases criticizing Cornyn’s vote. Even his allies turned on him. The Texas Medical Association, which has backed Cornyn in every election, withdrew its endorsement, and its national affiliate group, the American Medical Association, began airing television ads in San Antonio critical of his vote. “That [vote] really surprised a lot of people,” says Coppedge, who wrote Cornyn a strongly worded letter urging him to change his stance. Cornyn promptly flip-flopped on the Medicare bill, voting for it when it came back before the Senate in early July. He even voted to override Bush’s veto.

Physicians once again have been some of Cornyn’s most loyal supporters this election cycle; he has received $597,088 from doctors, according to the Center for Responsive Politics. Only lawyers and oil and gas producers have given him more. In all, the oil and gas industry has contributed more than $800,000 to Cornyn’s campaign as of March, including $50,500 from ExxonMobil Corp. Cornyn—alongside many Republican colleagues—has sided with oil companies in the recent debate over high gas prices. He wants Congress to allow offshore drilling and exploration in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge.

Though Cornyn has moderated some of his positions recently, there remains plenty of fodder for Noriega to contend that Cornyn has drifted too far rightward. Even Texas Monthly wondered, in a January story, if the junior senator hadn’t become too conservative for Texas.

His record does aid his popularity with one key constituency — the GOP Senate leadership. Leadership positions in Washington are usually awarded to hard-edged ideologues. “He’s seen as one of the rising stars in the Republican party,” Allen says. “The future for him is bright in terms of Republican leadership.” If Hutchison follows through on her promise to leave the Senate in 2010, Cornyn could soon become Texas’ most powerful voice inside the Beltway. That is, if he wins re-election.

–

Cornyn’s ultraconservative record and ties to an unpopular president aren’t his only problems this election season. He must also contend with a restless public that’s fed up with GOP incumbents in Washington. On top of that, many pundits are expecting a wave of Democratic voters to flood the polls this year because of the excitement surrounding the presidential candidacy of Barack Obama. Some polls by independent firms show the Senate race is close. Internal polling by the campaigns indicates that Noriega is within 8 points—striking distance—of Cornyn.

The question remains whether Noriega can take advantage. His campaign so far hasn’t inspired much confidence among Democratic insiders.

Cornyn has the good fortune of facing a candidate who may be a more wooden campaigner then he is. Though incumbent Cornyn isn’t well known, mentioning the name Rick Noriega will more than likely return you a blank stare.

At times, Noriega has seemed intent on introducing himself to one Texan at a time. In early July, he spent an entire campaign day in Loving County in far West Texas, not far from El Paso. Loving is the nation’s least-populated county (67 people reside there, according to the 2000 Census). Noriega traveled hours to give a speech on the courthouse steps. Five people showed up.

Most damaging of all, Noriega lacks the money to introduce himself on television. He has $915,000 in his campaign account, according to the latest federal filings. It costs roughly $1 million a week to air television ads in Texas, which boasts two of the nation’s priciest media markets. Cornyn has more than $9 million on hand.

The Washington-based Cook Political Report sized up the race in mid-July and deemed it “solidly Republican.” The GOP still has a built-in advantage in Texas that Cornyn would have to squander. He may not be the most exciting candidate, but he’s also known as a disciplined campaigner who rarely makes mistakes. The Cornyn campaign even believes the senator’s relative anonymity could actually benefit him. It hopes a disgruntled electorate that’s unfamiliar with Cornyn may not blame him for his party’s failings. Moreover, Cornyn, in his blandness and adherence to conservative orthodoxy, hasn’t alienated any large segments of the party. As one GOP insider pointed out in private, Hutchison, Gov. Rick Perry, and Lt. Gov. David Dewhurst all have entrenched factions of critics within the party. Not so Cornyn. It may be a down year for Republicans, but the ones who do come out to vote will stick with the senator.

Cornyn is vulnerable. Sure, he can be beaten. But three months before election day, the odds are against it.