The Year Nothing Changed

You remember 1968. That was the year everything changed.

The North Vietnamese began the Tet offensive, widely regarded as a turning point in the Vietnam War, and turned out to be the last gasp of American support for that doomed, faraway war. Lyndon Johnson announced he wouldn’t seek re-election. Martin Luther King Jr. and Bobby Kennedy were assassinated. Students rioted across the globe, occupying campus buildings and storming city streets, burning their draft cards in the United States. Feminists, then known as women’s libbers, threatened to burn their undergarments. Evidently no lingerie was actually singed, but that didn’t stop people from calling the libbers “bra-burners.” Women who threatened to burn perfectly good underwear were clearly capable of anything.

Even if you’re not old enough to remember 1968, you can learn about it in commemorative college classes, read about it in newspapers and magazines published in years that end in 8, and hear about it on TV reminiscences that usually begin, “It was 40 years ago today …” Because 1968 was the year everything changed.

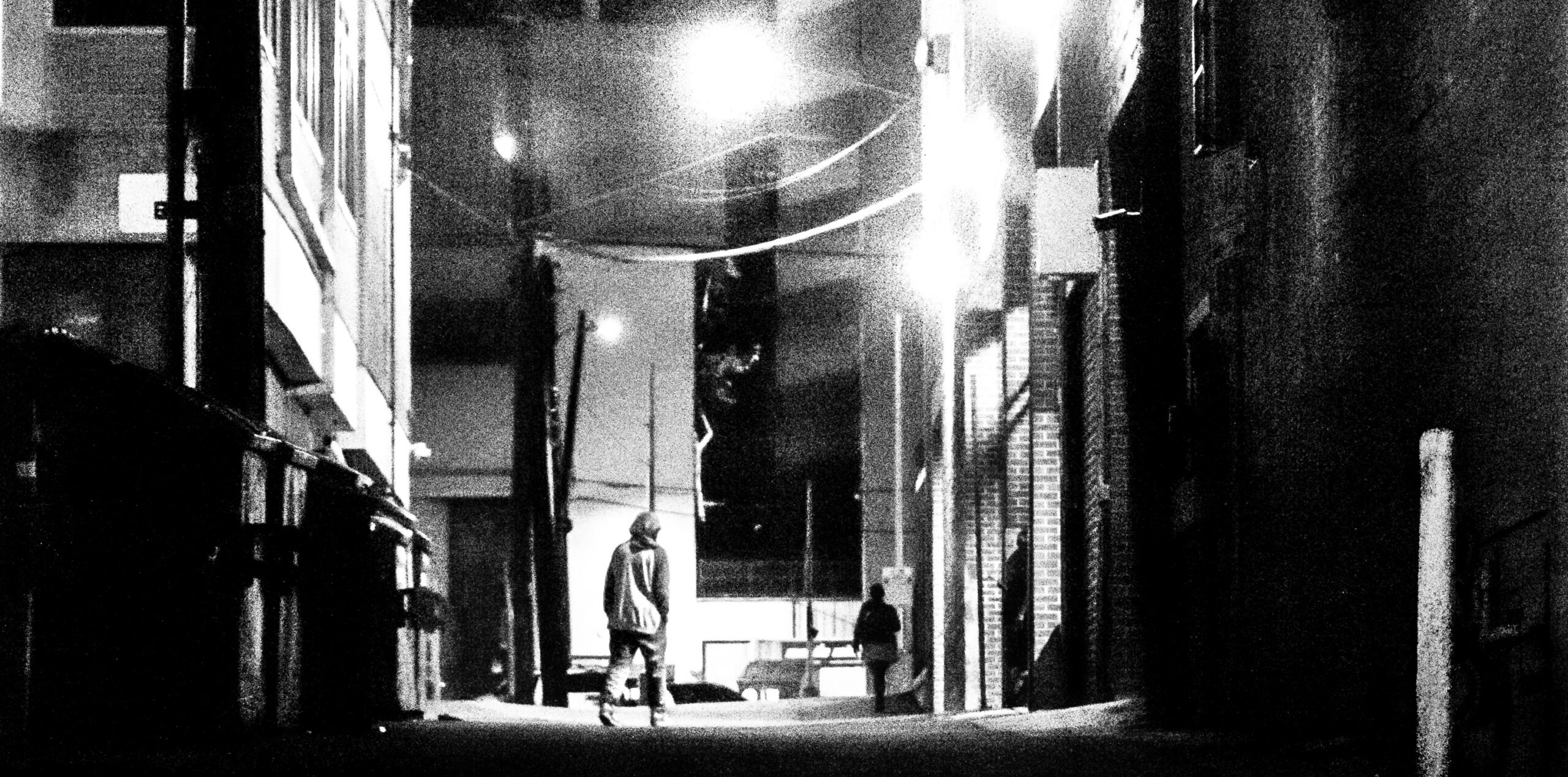

Except in Midland, Texas. There, the tumult of the late 1960s was a distant, black-and-white rumor, fed to us by people named Huntley and Brinkley and Cronkite. Men might be growing their hair long and going soft on Communism and smoking illicit drugs, and women might be getting all riled up even when it wasn’t that time of the month, but praise the Lord, everybody was still sane and conservative in Midland. Short-haired men pursued manly occupations like geology and dentistry, and women wore unburned bras and joined the Junior League and drank at the country club. The only political radicals in Midland were the John Birchers, who really weren’t as crazy as most of the country thought they were, and the small congregation of Unitarians, who were widely rumored to think and philosophize instead of pray.

The kids in Midland-well, they were mostly all-right, too. Who needed drugs when you could empty out your parents’ liquor cabinet?

Midland High School’s senior class of 1968 chose powder blue and royal blue as class colors, the yellow rose as the class flower, and To Sir With Love, which only Lulu could sing, as class song. MHS’s 1968 yearbook, the Catoico (an amalgam of the region’s economic bases of cattle, oil, and cotton, with an accent on the second syllable) shows an assortment of fresh-faced youngsters with bouffant hairdos and crewcuts. Even after then-recent school desegregation and the closing of the town’s only black high school, they were mostly Anglo-though that wasn’t a term anybody had heard of yet. They went to football games, they formed pep clubs, they joined choir, drama club, Future Farmers of America. They smiled in the yearbook. You can even find me smiling there, because you’re supposed to smile in your high school yearbook. In Midland, even in 1968, we mostly did as we were supposed to.

“They don’t know it,” the MHS band director told our parents at our band concert one spring, “but these are their golden years.” He nodded at the band, raised his baton, and we obediently started to play some song called “The Golden Years.”

At the back of the stage, thumping on a marimba, I wanted to slit my wrists. If these were our golden years, how much worse was it going to get?

It’s mortifying, but it’s true: In 1968, at least in West Texas, girls still pretended to be dumb when they were around boys. “I thought you were dumb,” the guy I ended up marrying always says. He and I were classmates at Midland High in 1968. We were acquaintances then, both of us in the band, but we didn’t like each other. I thought he was arrogant.

One day in 1968, when he was in the school counselor’s office, the counselor left the room for a few minutes. A grid of seniors’ SAT scores was on his desk. My husband, the future social scientist who now makes a living being nosy, looked over the SATs. Apparently he almost suffered cardiac arrest when he saw my scores.”I never would have dated you if I hadn’t seen your SAT scores,” he likes to say, still.

Since they were notably higher than his, I’m surprised he had the nerve.

In any event, his high school experiences and mine were entirely different, starting with the acting-dumb part. He fondly recalls Tom Sawyer-like escapades with his friends, shooting off fireworks and natural gas balloons, setting the neighbor’s roof on fire. They burned an “M” into the football field we shared with the other high school. They sneaked a Fizzie into a classroom fish tank owned by a despised science teacher; the fish expired, and the teacher was livid.

My own high school experiences were more the tragic, pining Emily Dickinson variety, except without the great poetry and genius. I read books, mooned over boys who didn’t know I existed, moped, suffered, wrote bitter and self-pitying journal entries, hated myself, and hated high school even more. My parents, both good-looking and popular in their early days, must have looked at the shy bookworm they’d somehow given birth to and wondered where they’d gone wrong.

I’d like to think that my tortured years were proof of the shallowness and cruelty of adolescence and my own deeply sensitive persona, but I’m sure I’m flattering myself. It’s never that simple.

Neither are high school reunions. Over the years, my husband has dragged me to three. The tenth was miserable, with attendees posturing and preening about their post-high school successes, and too many getting drunk. (OK, so one of the obnoxious drunks was me; I was having a bad year in 1978.)

The more recent reunions, at 20 and 25 years, were different, and much better. You usually don’t get to that point in life, when you’re settling uneasily into middle age, without life having damaged you in some way. Some classmates had died. Others had divorced or lost jobs. A number were in 12-step programs. I found myself talking to people I’d never shared a word with in high school, talking about books and families and losses.

At that point in life, it seemed to me, we had become who we were going to be. High school status and teenage cruelties didn’t matter the way they once had. Neither did our post-high school successes. Who was there to show off to, anyway? A bunch of adolescents who no longer existed, except in the yellowing pages of a yearbook?

Nope, that was all over. We’d grown up, moved on, healed what wounds we could. I left those reunions feeling comforted. High school was finally over.

Forty years after 1968, the country is embroiled in another doomed and unnecessary war, this one initiated by a president who spent a few childhood years in Midland and speaks of it warmly. After all his grievous mistakes and unforgivable blunders, George W. Bush still has many fans in Midland. I’d already learned that when I’d met an old high school classmate in Austin. She was deeply offended when I referred to Bush as an “asshole.”

“I’d prefer it if you didn’t use that adjective,” she huffed.

Actually, I thought, it’s a noun, not an adjective. Perhaps “moron” would have been more appropriate.

I digress. The point is, I was convinced that politics hovered more closely over Midland and the 40th Midland High School reunion than they had even in 1968. One of our classmates was rumored to have “saved” George W. Bush from the demon liquor. And John McCain had just recently spurned a fundraiser given by local oilman Clayton Williams, who’d made an unsuccessful run for Texas governor years ago. “It was that rape joke Claytie made in-what?-1990,” a Midlander told me. “That was 18 years ago. He already apologized for it. Hell, he called Ann Richards on her deathbed. What else does he have to do?”

Bad feelings toward McCain clearly persisted in Midland. I made a mental note to remember to mention that I’d heard McCain wasn’t really a conservative, kept his eyes open during evangelical prayers, and had suggested impeaching Bush and Cheney so Nancy Pelosi could become president.

I didn’t get the chance, though. Forget politics. The 40th reunion-held with the MHS class of 1967 and nearby Lee High School’s classes of 1967 and 1968-was as apolitical as high school in 1968. People squinted at nameplates with high school photos and too-small names. They swapped photos of kids and grandkids. They gathered around a table with 40-year-old photographs of those who had died, talking about cancer and suicide and unknown causes. A few danced; most didn’t bother. But the band was loud, and the lights were dim, and it was difficult to have a good conversation, even assuming you recognized anyone you wanted to talk to.

“Same old cliques,” sniffed one friend. The night before, he had mentioned wishing he could go back to high school knowing what he knows now. Why? “So I could be popular,” he’d said.

My husband and I spent time with him and other old friends from the high school band. We talked about whether we became nerds when we joined the band, or whether we joined the band because we were already nerds. Regardless, we agreed, it had given us a place to go, friends to be with. Band had made high school tolerable.

Talking about our memories, the other woman in our group-now a biology professor in New Mexico-and I had argued that girls had a far rougher time in high school in West Texas in the 1960s than the boys did. There was more pressure to be pretty and outgoing and popular-and, remember, not to act smart. If you didn’t meet those criteria, if you were as shy and awkward as we had been, high school was a painful experience. Boys, on the other hand, even if they weren’t bulky star athletes, had more freedom and less pressure to fit a narrow mold.

Now, even after 40 years, it’s remarkable how potent and vivid those memories are. All I can think is that, when you’re that young and everything is new, you’re imprinted more deeply by your experiences.

“I never dated much then,” said the guy who wanted to go back to high school and be popular. “But you know, there weren’t any girls worth dating in the band, anyway.”

He looked at the rest of us, the small group including two of those former girls he was talking about. How odd that after all those decades, after college and advanced degrees, husbands, children, feminism, a long list of professional and personal accomplishments between us, his remark still had the power to wound.

“You went to your high school reunion?” my yoga pal Ron Deutsch said after we got back. He stared at me, dumbstruck by my cluelessness. He shook his head. “You know, I told a European friend of mine that if he wants to understand Americans, he needs to understand American high schools. People here spend the rest of their lives trying to make up for what they were in high school-or trying to escape from it.”

Maybe I should have talked to him before I went to the damned thing. It wasn’t political. It wasn’t transformative. It was still high school, after all these years, reminding me of some almost-forgotten essence of myself. Just when I thought I’d gotten out of it, it pulled me right back in.

Ruth Pennebaker is an Austin writer, public radio commentator, and blogger at www.geezersisters.wordpress.com.