Deep in the Heart

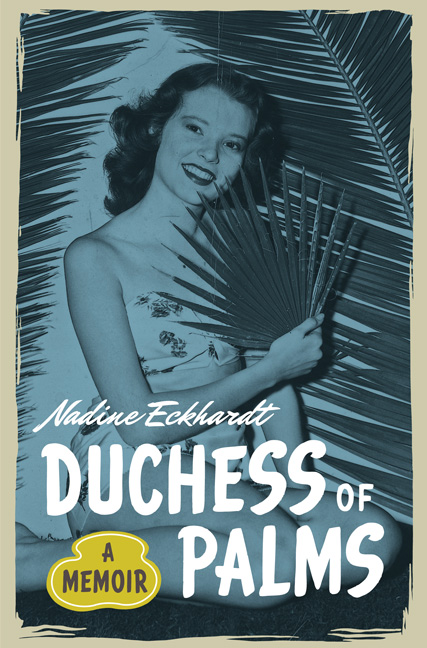

Reprinted from Chapter 2 of Duchess of Palms: A Memoir, by Nadine Eckhardt, copyright 2009 by permission of University of Texas Press.

It had been two years since I’d been back to Texas, and I was desperate to see the Texas sky and feel the sun burn my skin and warm my bones. My parents had missed out on seeing our little girls for too long. Although I enjoyed working in the Senate and knew I could advance in Lyndon’s organization, children came first. Anticipating being a mother of three had me yearning for Austin, where life was easier, cheaper, and healthier. Maintaining homes in both D.C. and Austin seemed financially impossible, but I insisted on it.

I wrote a carefully worded note to LBJ saying that only motherhood could take me away from him. The nurturing women on the staff arranged a party for my departure, which was held in Lyndon’s elegant majority leader’s suite. Lyndon put his arm around me and said, “If you’ll name that boy after me, I’ll give him a heifer calf and he’ll have a whole herd by the time he’s twenty-one.”

As my little girls and I flew back to Texas (this time on a commercial plane), I was hugely pregnant and happy to be returning to wide-open skies and life in Austin. (I thought I was through with Washington, but what I couldn’t have known then was that Lyndon Johnson would be a constant in my life-sometimes peripherally, sometimes centrally-until his death.) Bill and I had both been changed by working for LBJ. He taught us that both sides of an issue had to be weighed with the public interest in mind. He had little patience with extreme liberals or extreme conservatives, but he would work with both types, and he was usually successful in making them see his point of view. He spoke to us quietly, like a teacher, often dropping in one of his homilies: “Never trust a naryassed man,” “You ain’t learning anything when you’re talking,” and “Your judgment is only as good as your information” are just three of many.

On May 24, 1957, our son, Willie, named after our favorite journalist, Willie Morris, was born. Soon afterward, Lyndon and Bill both happened to be in Austin, and The Senator asked Bill to fly with him and Mary Margaret Wiley, his number one secretary, to Washington over the weekend to tend to an errand. Bill was home so seldom that he didn’t want to go, but I needed a break from child-rearing, so I called Lyndon and suggested that I go in Bill’s stead. The next day the three of us boarded an oil company plane (which, unfortunately, was not as comfortably pressurized as the Brown & Root planes) bound for D.C. We drank Scotch, of course, and Mary Margaret and I defended our liberal friends. Lyndon couldn’t let it rest. He didn’t like Ronnie Dugger, the editor of the Texas Observer, worth a damn. When his arguments failed to bring us around, he resorted to saying, “If you look back far enough in his [Ronnie’s] family, you’ll find a dwarf.” For his part, Ronnie didn’t like him either.

We passed a pleasant weekend in Johnson’s Washington home. Lady Bird was not there. The Senator tended to business between Scotches and gossiping and trying to get his two young companions to see things his way. He kept his hands to himself, seeming much more relaxed; I felt warmly toward him. Mary Margaret called the shots. She knew Johnson better than anyone. The younger members of LBJ’s entourage considered her a good influence because she was “one of us,” a younger, hipper staffer who prodded him to the left. And even though he was playing the political game just right by sending one message to the liberals and another to the conservatives, we were impatient and wanted more results.

Back in Austin, our politically conscious friends were obsessed with LBJ, wanting to know whether he was truly liberal or simply conservative. Was he as crude as they’d heard? They all wanted to meet him. I loved living with my children in the big, old, comfortable house on Enfield Road that Bill had rented and I had fixed up before Willie was born. A beautiful young Mexican-Irish girl came to live with me and look after the children in exchange for room and board. She had many brothers and sisters, so she was great with the kids. When she arrived after school, I went out with my friends. When Bill was home, we partied together, and when Lyndon was at the ranch, we spent weekends out there, including the children.

Lyndon and Lady Bird had created a Texas spread with all the comforts-all of their houses, in fact, were warm, accommodating, and without pretension. Lyndon was relaxed during this period. One day I was driving in the vicinity of the ranch with several friends and we decided to drop by, unannounced. We came upon Lyndon floating around in his swimming pool, happy to see us, with Wayne King blasting from speakers hung in trees.

Weekends at the ranch were much the same as those in Washington, but the atmosphere was far more relaxed. Lyndon held forth, telling stories and laughing, surrounded by staff, Jessie Kellum (his radio/TV station manager), Donald Thomas (his lawyer), and local cronies. We drank, ate, and gathered around him, listening and getting assignments for whatever it was he wanted. Lyndon soaked up the attention while Lady Bird saw to it that everyone had a drink and was comfortable. Zephyr Wright, the Johnsons’ black cook, churned out popovers and bowls of 1950s food served family style.

Lady Bird always seemed busy and preoccupied-the same criticism voiced by my children later, when I was a congressional wife. At the time Bill and I were too young to appreciate Lady Bird’s importance; I think that’s why Bill gave her short shrift as Sweet Mama in The Gay Place. He didn’t understand how crucial she was to enabling Lyndon’s power-and neither did I, until I was a congressional wife. After observing The Senator’s behavior with female staff members and women in general, I often wondered how Lady Bird put up with him. His womanizing was obvious. He would holler “BIRD!” if he wanted her attention, and like magic she would appear. He sometimes humiliated her in front of other people. But Lady Bird was of another generation, wise enough not to respond to his crudeness. She was willing to ignore his behavior, for she was secure in her position as his wife, and he needed her and loved her in his way. Also, she desired power just as much as he did. Theirs was a creative relationship that served to accomplish their mutual goals for money and political power. She had to either compromise and put up with the guy, or leave-so she compromised. I think Lady Bird was a superb First Lady. When Lyndon died, she inherited the money and prestige of everything they had built, all of which she richly deserved. When she spoke, it came from a very high place.

During this time, 1957-1958, Bill was living in a basement room in the Betty Alden Inn, because it was cheap and near the office. He hated it. He was working on his novel at night and bemoaning our separation. Although Bill and I both acknowledged that Austin was the best place to raise our children, living separately was eroding our marriage. I felt the sting of the separation too, but the thought of moving back to Washington with three children was unthinkable. There was one good thing that came out of this difficult time, however: Bill’s loneliness, his living space, and his liberal use of amphetamines imposed a discipline of sorts, and he finished work on the manuscript that became The Gay Place.

Bill’s letters reflected his sadness, but at the same time, he was having a very interesting life. He traveled to New York City frequently. He also spent time with LBJ at George Brown’s place. His letter of February 3, 1958, describes the scene:

Left here about 3:00 Saturday in the limousine. Jenkins, Thornberrys, LBJs, and Mary Margaret and me. It was a lot of fun. The Virginia country was beautiful after the snow. We got there about 5, immediately started drinking, had people waiting on us hand and foot, had a sumptuous meal. Everybody turned in about 8 but I stayed up until midnight watching TV, playing records, reading books. Also there was George [Brown’s] or Herman’s adopted daughter, I don’t know which, and a friend of hers, both Smith girls, very intelligent and liberal. They were holidaying. Same routine Sunday, more drinking (milk punch in the morning), storytelling, very pleasant, no LBJ scenes, everybody relaxed and beautiful. Another enormous meal, with servants hovering all over. Best story: LBJ talking about Shivers, about last year after their fight. Shivers called him one day just to “pay respects.” LBJ invited him to hotel room in Austin for a drink. Shivers said Bill Francis is here, invited him over for a drink to his hotel room instead. Said they sat there from 3 in afternoon until midnight, “Allan with a fifth of bourbon and me with a fifth of Scotch … Bill Francis passed out about sundown; we sat there throwing lances at each other, dodging, jumping like stuck pigs when we was hit. Finally carried Bill Francis out into the limousine at midnight.” LBJ said: “I guess we understand each other.” Somebody said, “He used to love the people,” and LBJ said “Yes, but doesn’t anymore.” LBJ waved his arm about the room and said, “Here’s how you forget. You sit here at a big dining table before a crackling fire and carpets three inches thick. Now tell me. Are you very worked up about the suffering in the world at this moment? That’s what you got to watch out for.” That man!

“That man” would be elected vice president of the United States in just two short years.

Read more: Nadine Eckhardt dishes on life in the shadow of semi-famous men.