In its first issue, on December 13, 1954, the Texas Observer ran a political cartoon by Don Bartlett taking a swipe at the Republican-leaning tendencies of Democratic Governor Allan Shivers. Beside it ran Observer founding editor Ronnie Dugger’s ambitious, if eccentric, manifesto. “We will twit the self-important and honor the truly important,” he wrote. “We will lay the bark to the dignity of any public man any time we see fit.”

It was the beginning of a long Observer tradition—skewering those who needed it, using both printed words and the sharp sword of cartooning. “The cartoons arrived this morning … precise and timely,” Dugger wrote to Bartlett. “I believe I shall put [one of them] on Page One for maximum effect.”

Elsewhere, the tradition of editorial cartooning is waning fast. The membership of the Association of American Editorial Cartoonists has dropped from a high of more than 200 in the 1980s to less than 20 in recent years. Last July, three Pulitzer Prize-winners were fired in one day, when McClatchy, owner of the Fort Worth Star-Telegram, dropped staff cartoonists from its papers.

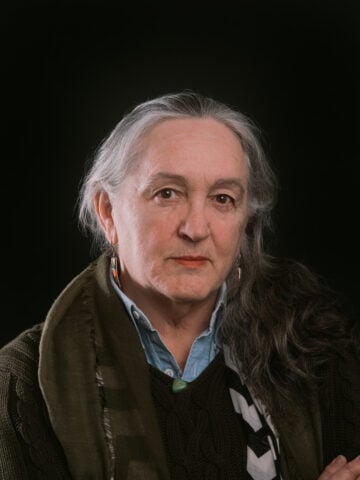

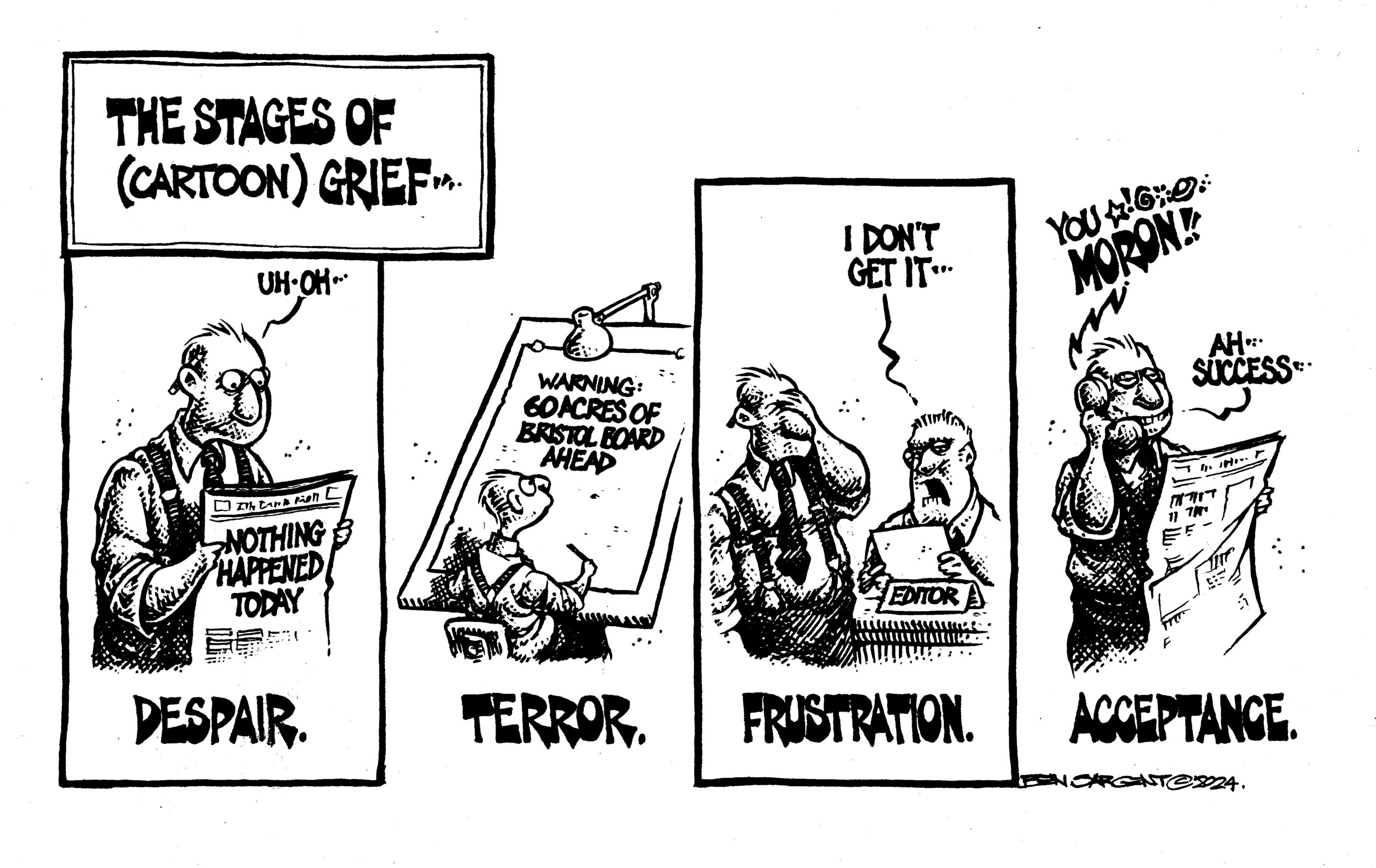

At the Observer, another Pulitzer Prize winner, Ben Sargent, has been drawing the “Loon Star State” cartoons for 15 years. Before that, he worked as staff cartoonist for the Austin American-Statesman. And before that, as a college student in Amarillo, he was already reading the Observer—and carrying the magazine around “to show what a radical I was.”

Losing political cartoonists is like losing “a lot of watchdogs barking at night,” Sargent said. “At times like these, that’s really kind of scary.” Some have found work online, but it’s not the same as working for a local publication. “You knew who you were talking to. It was the community campfire. Now it’s a sandstorm of information.”

Sargent said cartoons reach readers’ subconscious. Jack Ohman, president of the cartoonists group, agrees. “They do hit you viscerally,” he said.

It’s hard to say how many cartoonists’ work has appeared in the Observer in the last 70 years. But at the Briscoe Center for American History, the Observer archives include broad, flat boxes with stacks of original artwork from Bartlett and others dating from 1954 up until cartoons, like so much else, went digital and began arriving in editors’ email.

Sargent said he was pleasantly surprised, when he looked through that archive recently, to see how many top-notch cartoonists have done work for the Observer, including a Pulitzer finalist, two Pulitzer Prize winners (including Sargent), at least two elected officials, and a handful of the state’s best-known poster artists.

Some signed their work with just an initial or two, a last name, or a symbol. Kaye Northcott, co-editor of the Observer from the late ’60s to 1976, could decode some of those. One set of clever cartoons, including one showing former Governor John Connally dressed like a mobster and holding a violin case, were signed only with a “G.”

“That was Gerry Doyle,” Northcott said. “He started sending me things in the mail. They were spot-on drawings of political people.” Doyle was from the Beaumont area, she said, but “I never met him. I never asked him for anything. He would just send them.”

The help was greatly appreciated since, for the first couple of years Northcott was there, the Observer lacked an art director. “God, I didn’t know what I was doing” in terms of layout and art, and her co-editor Molly Ivins was worse, she said.

But Northcott had a close relationship with Austin’s famous Armadillo World Headquarters music venue and got to know the poster artists who did work there. Northcott commissioned many pieces of art from Jim Franklin, Michael Priest, and Danny Garrett. “Danny Garrett signed his with a palm tree,” she said.

Aha! At least one of his palm tree-signed sketches was in the archives.

Northcott also used cartoons by two people who were probably drawing them at their desks in Austin and Washington D.C.: Neil Caldwell, a Texas state representative and later a judge, and Bob Eckhardt, who also served in the Texas House and then won six terms in Congress.

Current political cartoonists may be even more cynical than their predecessors, given the state of their profession. But their signature sense of humor is mostly intact.

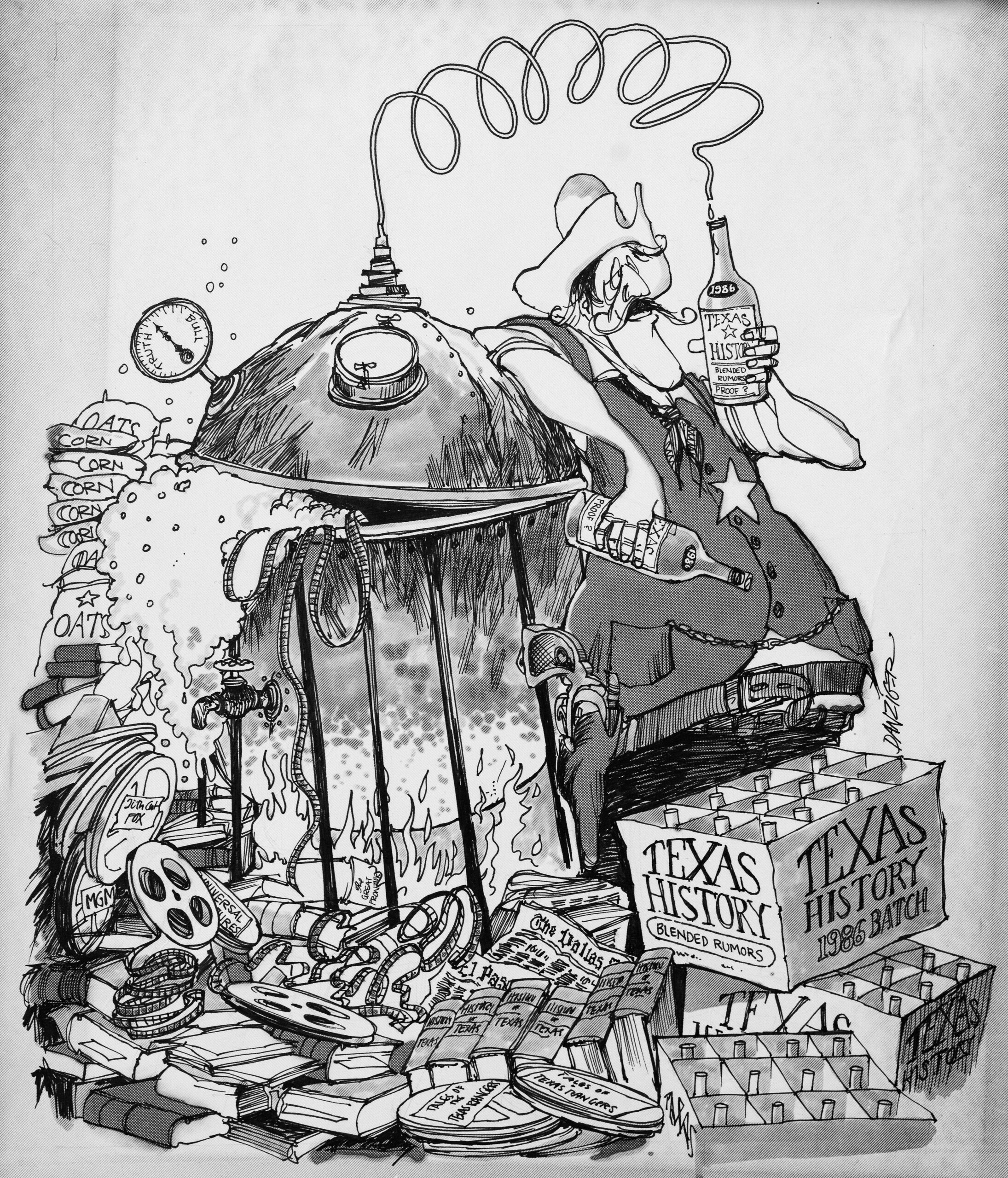

Jeff Danziger, twice a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize in editorial cartooning, drew for the Observer in the late ’70s, after the U.S. Army introduced him to Texas. “I’m 80. I never made much money in cartoons,” he said. These days, “Americans don’t know much, and they don’t want to know,” he said.

Fortunately, the situation for cartooning in other parts of the world is better. “The French love it. The Brits are the best,” Danziger said.

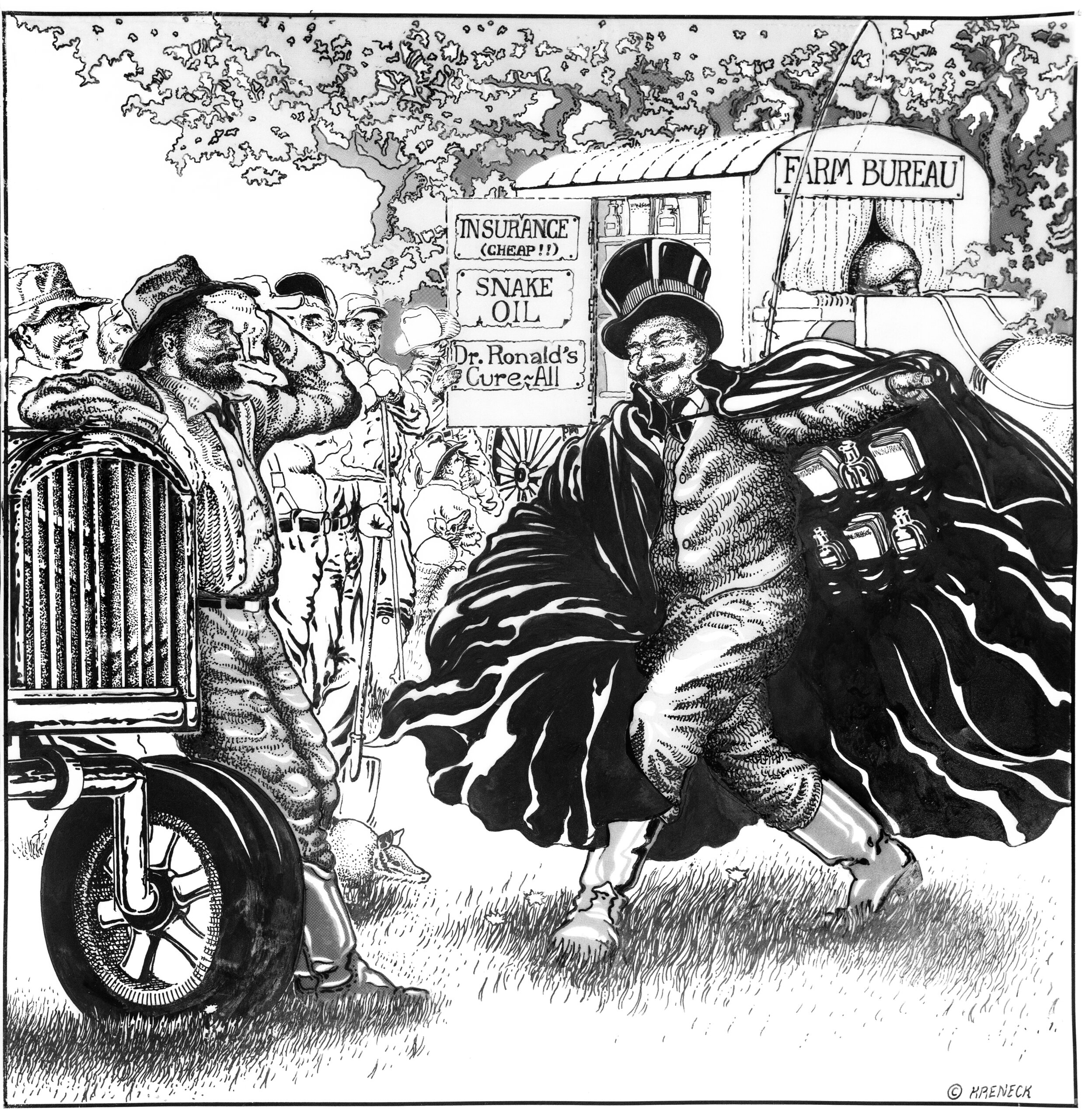

Kevin Kreneck of Dallas loved drawing for the Observer in the ’80s and ’90s. When he became syndicated, that provided enough money to live on. He also taught, to get out of the house than for the income. “Now, classes are a main source of revenue,” he said. “Cartooning—I do it because I love it.”

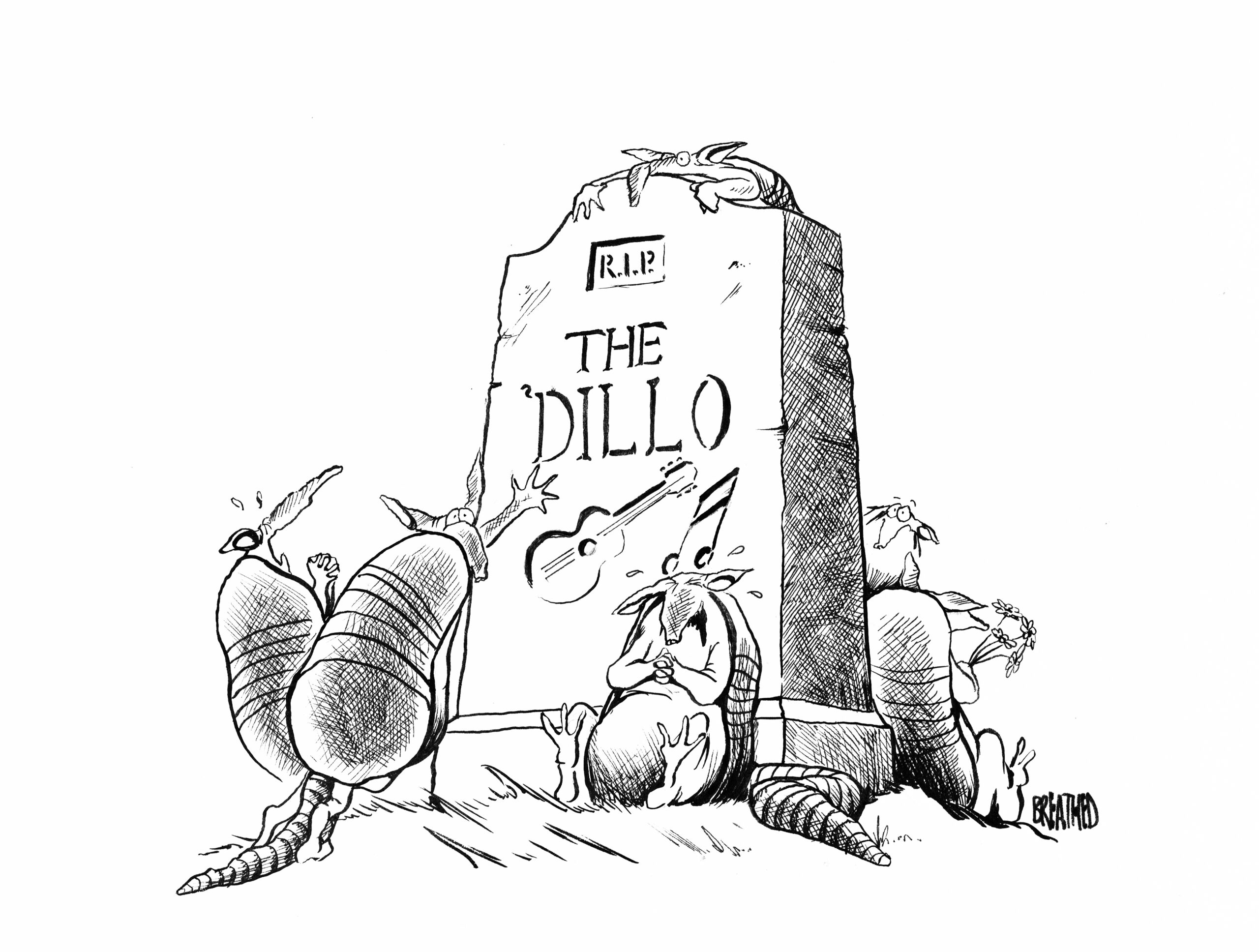

Berke Breathed drew for the Observer around 1980—the only journalism job he didn’t get fired from, he said. His vastly popular Bloom County strip won the 1987 Pulitzer for editorial cartooning. He called such cartooning “the adding of funny drawings to the words … the magic dust that all of us discovered and refuse to let go.” The problem now, he said, is the decline of people’s interest in the words.

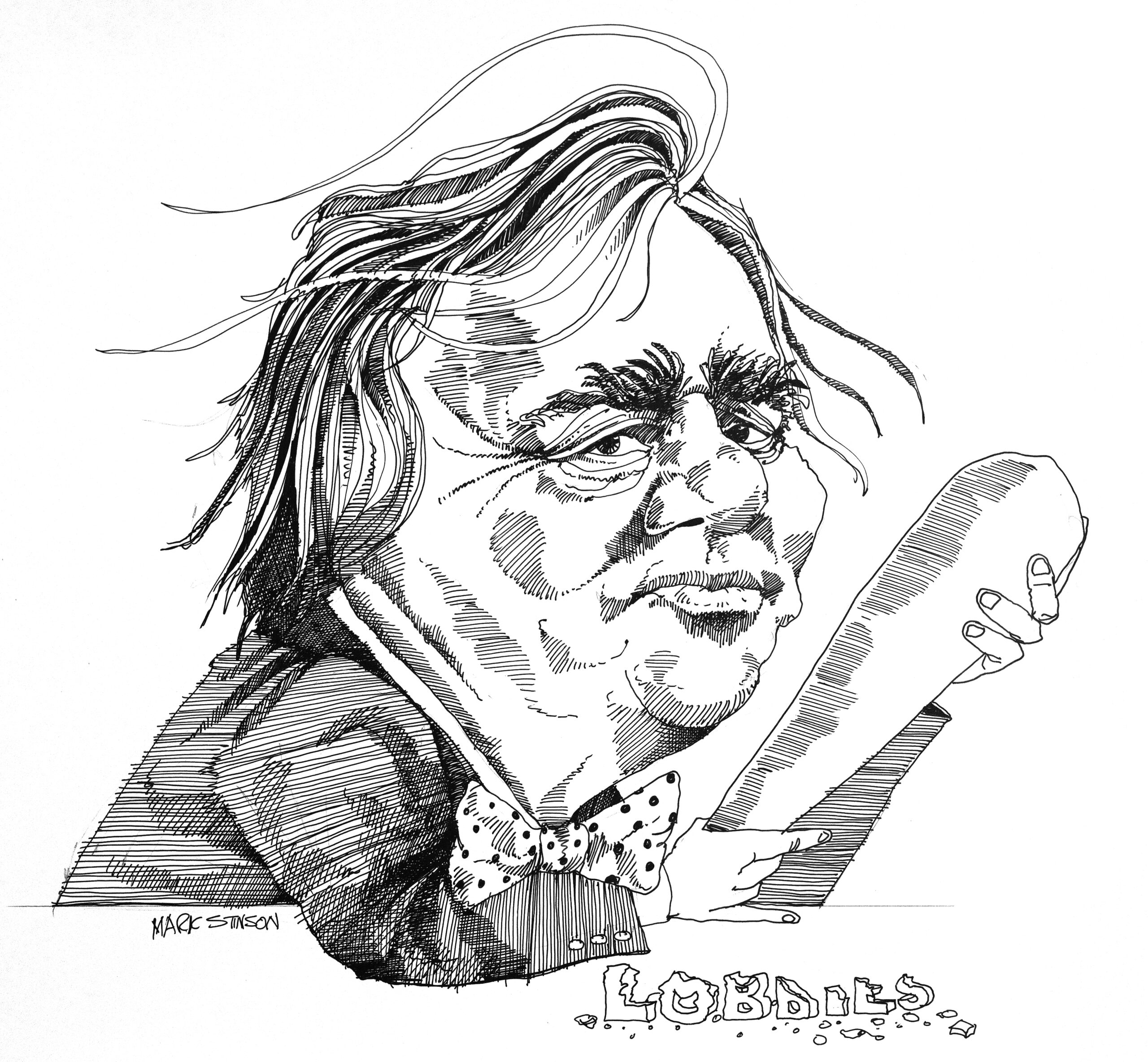

Mark Stinson mostly drew for the business side of the Observer while a college student in the early ’70s. He went on to work for two decades as an editorial cartoonist, including at the Houston Post. Now retired, Stinson said he misses the excitement of a newsroom. One day he walked into the office and the editorial writers started clapping for him. Why? “You got two death threats!” one of them told him.