Afterword

Writers of America, Unite!

Recently, I ventured into a nearby public elementary school to conduct a “writer’s workshop” for fourth and fifth graders. Organized several years ago by a few dedicated parents, who enlist a dozen local writers to come teach for a morning, the annual writer’s workshop is the sort of activity that Texas schools may squeeze in at the end of the year, after the spring battery of standardized testing has ended.

I’m no teacher–I’m not even a parent–and so I had to suppress a certain amount of panic as I stood before a roomful of small, rather devious-looking heads. But it must have been too early in the morning for insurrection, and in two hour-long sessions, my pint-sized, pencil-wielding charges applied themselves with a diligence that would put any professional procrastinator (like me) to shame. By the end of each class the students had written stories about skateboarding adventurers, divorcing parents, and Vince Carter. It was all very enjoyable and heartening until, with a few minutes left at the end of second class, I asked the kids what books they’d been reading this year.

No one responded at first. Then a boy said his teacher had asked them to rewrite a few fairy tales. Somebody else said “independent reading.” I asked what they’d read for “independent reading,” and another pause followed. Finally, a girl allowed that she’d read a book called Sometimes I Don’t Love My Mother.

From talking to a parent, I already knew something of the struggle it had been for this school to integrate both test-prep drills and more creative activities into the curriculum; the writer’s workshop may only take place in late spring, after the tests are over. And I’d read newspaper articles about how preparing for the annual TAAS tests in reading and math has led some schools to de-emphasize other subjects, like science and history. What hadn’t hit home until that morning was the extent to which some teachers have replaced books with test-prep materials.

The day after the workshop, I ran into a friend who teaches reading to sixth graders in another local school, and I asked her about her curriculum. Until this year she’d taught in California, and at the outset of her first year in Texas, she said, she’d planned on doing the sorts of activities she’d done in the past, like reading books and putting on plays. But after a month or so she was handed a stack of TAAS test objectives, with material to be covered each and every week–such as using a highlighter pen to highlight important words in a test question. They didn’t read any books all year.

If you are a writer hoping for a future audience, this is bad news. No early-career writer could survey the contemporary media landscape and feel confident that she had entered a growth field, but Harry Potter had me fooled. Kids are reading books, I thought. Without a little reinforcement from the public schools, however, I’m not sure whether we can rely on mass marketing and movie tie-ins alone to keep authors solvent.

Writers are good at complaining on paper, but we are going to have to get better at that slightly more refined form of whining known as government relations. When Bush’s bill to expand testing nationwide passed last fall, the novelists’ lobby, never a real force on K Street, was nowhere to be found. And even if they had been present, we can imagine what effete arguments they might have tried to pass off: that literature is somehow important, that reading literature may enhance one’s sense of the diversity of experience and life’s moral complexity, that literature is a cultivator of imagination and empathy. The scholar Martha Nussbaum, for one, made this case eloquently in her 1995 book Poetic Justice, but that is just not the type of thing that gets heard over politicians’ rallying cries for global competitiveness. When elected officials call for improvements to the education system, by and large they seem to refer to a system for producing employees. They align themselves with Mr. Gradgrind, the anti-storybook, pro-economics teacher in Hard Times by Charles Dickens (a British author who used to be widely read).

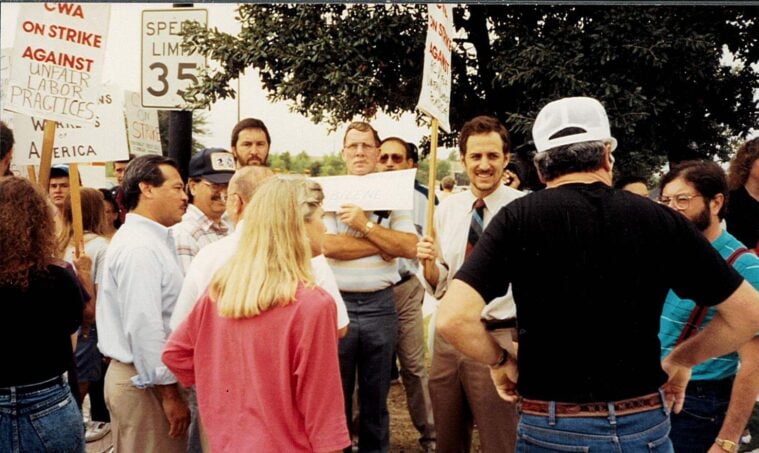

No, we can’t afford to waste our time on high-minded appeals from smart people, or trying to explain who Charles Dickens was. The answer for writers can be summarized in two words: price supports. Even now, book-writing is an activity which, like peanut or tobacco farming, the market does not always sustain, and with test mania metastasizing through the school system, the situation is bound to get worse. Yes, our opponents may tell us that literature is useless, but then again, how badly does the nation really need mohair? In order to obtain the subsidies we deserve, writers should undertake a coordinated “grassroots lobbying” effort, bankrolled by the publishing industry, and bombard officeholders with thousands of identical, well-written e-mails. Eventually, all writers will need to move en masse to a key swing state such as Pennsylvania in order to have more of an influence on the political process.

In the meantime, we may have to rise from our desk chairs and take direct action to preserve our audience. The next time you pass by a schoolyard late at night and see a bespectacled, unathletic individual furtively hurling copies of The Adventures of Tom Sawyer over the fence, you’ll know what’s going on. It’s just another writer acting out of self-interest–but also hoping, perhaps, that the sensible goal of requiring students to demonstrate basic skills will one day be brought back into balance with the expectation that they be truly educated.

Karen Olsson will continue to cultivate imagination and empathy from her home in Austin.