A Catch-22 in the Crimmigration System in Harris County

In Houston, a lack of transparency and poor communication between immigration and criminal courts has created a civil rights nightmare and a clog in the system.

Abysmal record-keeping and an increasingly secretive immigration force have created a catch-22 for undocumented defendants accused of low-level crimes in Houston.

After being arrested and meeting bail conditions set by Harris County magistrates, these defendants are often transferred to federal detention centers rather than released until their day in court. But as they languish in Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) custody, sometimes for months, they are asked to do the impossible: show up for their Harris County court hearings.

Without a system in place to track defendants in ICE custody, many undocumented immigrants register in the county’s conveyor-belt justice system as just another person missing a court appearance. The penalties for missing court are serious: Bonds can be raised or revoked, and the court can issue arrest warrants or new citations in a revolving-door scenario reminiscent of a Kafka novel.

“It’s a particularly cruel form of double jeopardy,” said Jay Jenkins, an attorney with the Texas Criminal Justice Coalition, a nonprofit that aims to reduce mass incarceration.

Legal experts question the legality of revoking a person’s bond while he or she is in immigration lockup. The Texas Code of Criminal Procedure states people shouldn’t lose bail if they miss court because of “incarceration.” This crimmigration loop also hinders people’s ability to fairly defend themselves and can be used to coerce guilty pleas or voluntary deportations, according to Jenkins and Angie Junck, an attorney with the Immigrant Legal Resource Center. Unlike criminal courts, respondents in civil immigration court (even toddlers) do not have the right to an attorney.

Harris County Criminal Court at Law Judge Darrell Jordan told the Observer that no systemic steps have been taken to fix the “roller coaster” of a problem. Jordan, the only Democratic misdemeanor court judge in Harris County, laid blame on a criminal justice system that doesn’t check if defendants are in ICE custody before issuing new fines and citations.

“I think there is a lack of compassion. The solution is individualized attention to each case,” Jordan told the Observer. “I would say to anybody, one day in custody when you shouldn’t be there is too long. Let those people go sit in a jail for 90 days and see how it affects their life.”

Tom Berg, first assistant to Harris County DA Kim Ogg, said his office doesn’t “treat immigrants differently” and that “there’s no discrimination.”

“We don’t seek ICE custody for these people,” Berg told the Observer. “We have no control over what happens in the federal system.”

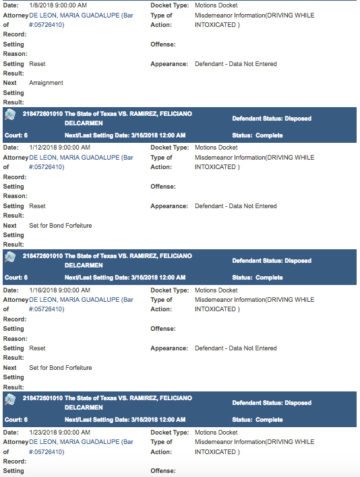

Regardless, the consequences are serious. Take the case of Feliciano Ramirez, a 60-year-old auto mechanic from Mexico who was arrested January 7 for allegedly driving while intoxicated. Though Ramirez made bond, he was held in jail at the request of ICE, which took him into custody the next day, according to court records. Ramirez then missed Harris County court dates for the DWI charge on January 8, 12, 16, 23, 24 and 30 while in federal immigration lockup, court records indicate. On January 30, Harris County Criminal Court Judge Larry Standley ordered that Ramirez’s $500 bond be revoked.

“The Defendant’s name was distinctly called at the courthouse door,” Standley wrote in his judgement. “After waiting a reasonable time, the Defendant failed to appear.” Standley did not respond to multiple requests for comment. Reached via Facebook, Ramirez, who was ultimately deported, confirmed the details of his ordeal. “I spent half my life in the United States,” he said. “They chained me hand and foot and gave me to Mexico: That was the process.”

Harris County District Clerk Chris Daniel’s office couldn’t provide information on how many bonds have been revoked for failure to appear in court in 2018. The Harris County DA’s office also couldn’t provide data on bond forfeitures. No official record exists of how many forfeitures were a result of a defendant being stuck in ICE custody.

Without official data, the Observer analyzed more than a week’s worth of court dockets (9,527 case files total) and spoke with defense attorneys and court employees to come up with a rough estimate: Five to 10 percent of the thousands of annual forfeitures currently involve people who can’t make court because they’re in ICE detention.

Nobody seems to know how long it’s been going on, either. Jennifer Gaut, a Harris County assistant public defender, said the problem became more evident last year as the county was under a microscope following a federal ruling that its bail system was “unconstitutional.”

Attorneys described hellish situations in which — after being ferried between detention centers and the courthouse on the “ICE bus” — some clients wanted to be deported but weren’t. It’s possible for ICE to deport immigrants with pending criminal cases, but in practice, attorneys say lingering charges frequently slow down or halt immigration proceedings.

“It’s a particularly cruel form of double jeopardy.”

While Houston isn’t alone in what criminal justice advocates called a cruel practice, it’s home to the third-largest undocumented population in the United States. Two privately run immigration detention centers, with a combined 2,500 beds, are within an hour of the Harris County courthouse.

Jordan said he has taken steps to mitigate the problem when it comes before his court. For example, Ramirez, the auto mechanic who missed at least six appearances, was finally brought to Harris County court on March 16 — this time to Jordan — more than two months after his DWI arrest. Ramirez accepted a plea deal that resulted in a 20-day jail sentence, records show. Jordan gave Ramirez credit for the 65 days he served in immigration lockup and released him back to ICE, his Class B misdemeanor finally resolved.

“We get a lot of money to be here for two and a half hours a day,” Jordan said. “We should be solving problems.”

Mana Yegani, an immigration attorney in Houston, has started advising undocumented clients to refuse bail and stay in county jail after an arrest, so that they can resolve their criminal charges before being transferred to ICE.

Berg, the first assistant DA, said the DA’s office will “generally join [defendants] in trying to reinstate a bond” if a defendant can prove they were in ICE detention during their appearance. However, ICE provides no “print-out” to lawyers or judges that could be used as proof that they were in immigration lockup, said Alan Macias, a defense attorney in Houston. Nor is ICE apparently coordinating with judges or prosecutors.

Tangled bureaucracy and a lack of transparency seem to be feeding the problem. The Harris County Sheriff’s Office said it’s prevented by state law from disclosing who was transferred to immigration custody. ICE refused multiple requests for comment for this story unless the Observer gave them an “intent to publish” letter. (We didn’t.) The ICE public information office said it could take up to two months to get data on who the agency has taken from Harris County jails.