In early September 2015, guards fanned out across Texas with orders to round up about 200 men, rousing some from bed as early as 3 a.m. and demanding they stuff whatever they wanted to keep into black Hefty bags.

The men weren’t hard to find. They’d all completed lengthy prison sentences for sex crimes. The state calls them “sexually violent predators,” men required not only to publicly register their whereabouts but also to participate in a court-ordered monitoring and treatment program meant to cure them of “behavior abnormalities” and safely integrate them back into society after they’ve done their penance. At the time of the roundup, most were living in boarding homes and halfway houses.

Jason Schoenfeld, who was staying at a Fort Worth halfway house at the time, made a frantic phone call to his friend John, a fellow veteran. John, who’s retired and old enough to be Schoenfeld’s father, met the 46-year-old Gulf War veteran while volunteering at the Fort Worth VA hospital. John taught Schoenfeld breathing techniques to calm his nerves during an exercise class he’d volunteered to lead at the VA; records show the VA gave Schoenfeld a 30 percent disability rating for post-traumatic stress disorder after his combat service. John eventually grew fond of Schoenfeld and wanted to help him, even after learning his new friend had served an 18-year prison sentence for aggravated sexual assault of a child.

John says he heard desperation in Schoenfeld’s voice as he asked whether John could come grab his stuff before it ended up in a dumpster. “It was clear he didn’t have anybody else,” John told me. He says Schoenfeld looked confused to the point of tears when John and his wife arrived at the halfway house. “We didn’t even know what city he was going to,” John says. Schoenfeld gave him two bulging garbage bags; John now stores them in his home.

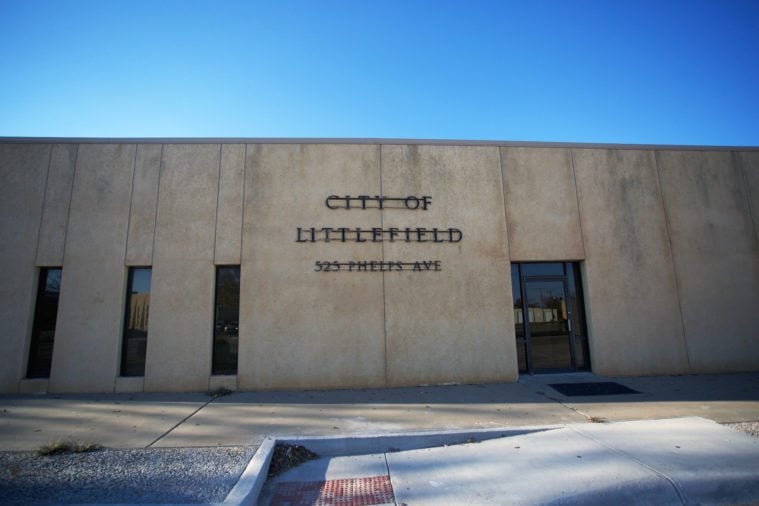

Schoenfeld and the others were frisked, loaded onto vans and prison buses and driven hundreds of miles to Littlefield, a remote, sparsely populated corner of the Texas Panhandle, where guards shuffled them into the Bill W. Clayton Detention Center, a prison that had been empty for six years.

Once inside those old prison walls, the men surrendered their IDs, Social Security cards, birth certificates and credit cards, along with cash and coins. Guards dug through the Hefty bags, tossing out all sorts of personal items now considered contraband. They went from living in halfway houses that looked like motels to windowless cells with cinderblock walls, hard steel bunks and metal toilets. But officials at the detention center were adamant: This wasn’t a prison. They instructed the men to call their living quarters “rooms,” not prison cells.

Unlike at the halfway houses, the new inmates couldn’t come and go. It wasn’t clear when their sentences would end, if ever.

Two and a half years after the Texas Civil Commitment Center opened its doors, only five men have been released — four of them to medical facilities where they later died.

State officials claim Texas’ new civil commitment program is designed to rehabilitate the men. But their families and friends argue the state has simply stashed them in a for-profit prison on the outskirts of the state, far away from the support services they’ll need if there’s any hope of transitioning back into society — the supposed goal of the facility. Lawyers who represent them consider the state’s new program an unconstitutional extension of the prison sentences the men have already served.

Critics of private prisons see in the Texas Civil Commitment Center the disturbing new evolution of an industry. As state and federal inmate populations have leveled off, private prison spinoffs and acquisitions in recent years have led to what watchdogs call a growing “treatment industrial complex,” a move by for-profit prison contractors to take over publicly funded facilities that lie somewhere at the intersection of incarceration and therapy. In Texas, their recent attempts to privatize two state psychiatric hospitals failed after families and advocates raised concerns that cost cutting to boost profits would jeopardize the quality of care.

The Texas Civil Commitment Center, however, was a quiet coup that few people saw coming. In 2015, the state signed a $24 million contract with Correct Care Solutions to run the facility; the contract was extended in 2017. The recipe for creating a new for-profit lockup in the era of decarceration: a state agency imploding under mismanagement, a private prison contractor on the rebound and a desperate town saddled with a mountain of debt and an empty detention center. Oh, and sex offenders.

Many of the problems that haunt private prisons elsewhere are evident at the center. Documents I obtained under state open records laws show a steady churn of staff since the prison reopened. The men confined there say that the turnover makes it impossible for them to advance in treatment, which is their only way out of indefinite detention. Correct Care has been scolded for delays in providing medical care and for repeatedly failing to conduct or document all the therapy that taxpayers are now funding.

Unlike at the halfway houses, the new inmates couldn’t come and go. It wasn’t clear when their sentences would end, if ever.

As the tab for sex offender treatment grows in Texas, the state and Correct Care have found creative ways to squeeze more money from the 277 men now incarcerated in the Littlefield facility, or rather from their families and friends on the outside. While state law allows the program to take a third of any income the men receive in order to help pay for their treatment and confinement in Littlefield, people who send packages to the facility say the company has now applied the concept to gifts. Anyone sending a package to an inmate must submit a receipt for whatever’s inside so officials can charge the sender a third of whatever it’s worth.

Some of the men are still required to help pay for ankle monitors, despite their new home being surrounded by a perimeter of two security fences topped with concertina wire. Inmates say that offenders who get in trouble sometimes end up in solitary confinement for weeks or even months at a time.

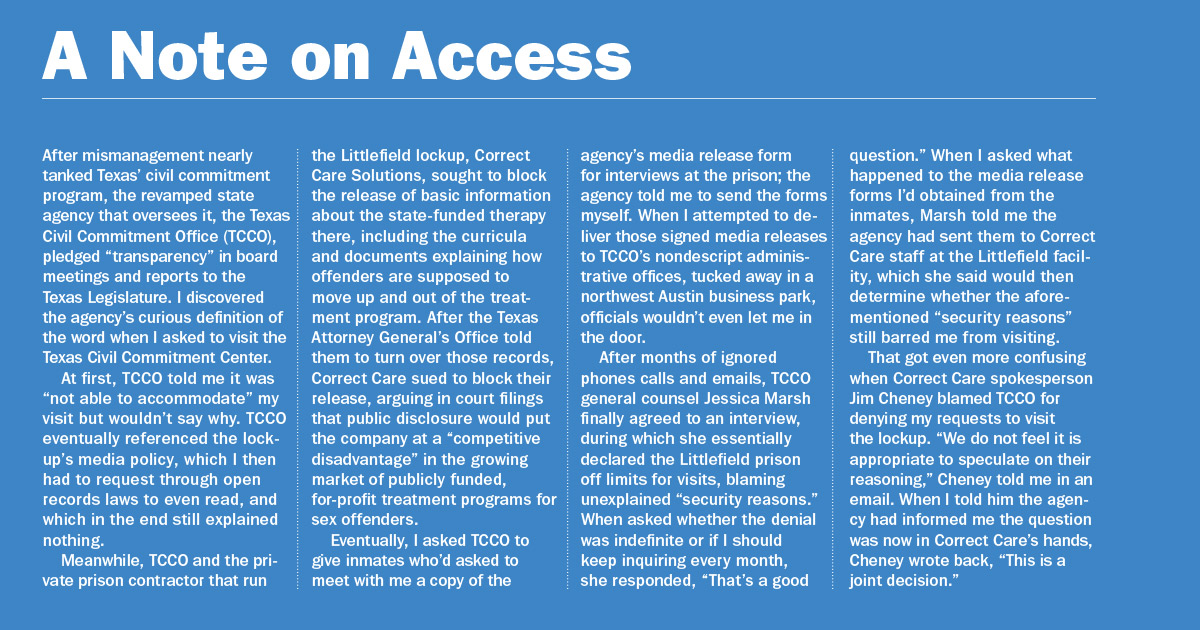

The not-a-prison prison operates with more secrecy than most supermaxes. For months I’ve asked to tour the detention center and interview inmates about the conditions there. The agency that oversees the program, the Texas Civil Commitment Office, has refused to answer many of my questions, including why they won’t let reporters inside the for-profit lockup.

Officials did, however, instruct me not to call it a prison and to refer to the men as “residents” instead of inmates.

It’s a point they apparently like to stress. When I visited Littlefield in December, a clerk at the motel where I was staying quickly corrected himself after telling me about the Texas Department of Public Safety notices he gets each time a new inmate moves into the detention facility. I let the word slip again while standing at the front door to the Texas Civil Commitment Center, where a gate is topped with coils of razor wire and a sign directs visitors to store cellphones, tobacco products or any other “illicit contraband” in their vehicles.

“FYI, we don’t have inmates here,” a faceless voice over an intercom told me. “We have residents.” When I started taking photographs, a Correct Care guard ordered me to leave the parking lot.

In the 1990s, heinous and headline-grabbing crimes committed by recently released sex offenders grabbed the nation’s attention. Lawmakers across the country reacted by adopting so-called sexually violent predator laws that created the process of civil commitment, which allowed states to hold worst-of-the-worst offenders long after they finished their sentences. Today, about 20 states can detain certain sex offenders for what they may do in the future, sometimes indefinitely.

Critics of the practice compare it to “The Minority Report,” the short story by Philip K. Dick where police predict the future and pre-emptively arrest people for crimes that haven’t yet happened. In the story, authorities use a trio of mutant “precogs” who can see the future. In civil commitment, authorities use polygraphs, plethysmographs (a device that tracks blood flow to the penis to measure arousal) and any number of risk-assessment tools — most of which have come under academic and legal scrutiny — to determine whether sex offenders are dangerous enough to detain, even after they’ve served their time.

Lawmakers created civil commitment for public safety reasons, but tried to make it constitutional by calling it treatment. The U.S. Supreme Court first upheld civil commitment for sex offenders in 1997, ruling that states can confine people who “constitute a real, continuing, and serious danger to society” so long as they’re in treatment, not prison. In a concurring opinion, Justice Anthony Kennedy warned that states whose programs morphed into a “mechanism for retribution or general deterrence” wouldn’t withstand judicial scrutiny.

Officials at the detention center were adamant: This wasn’t a prison.

The civil commitment program that Texas created in 1999 was unique in that it committed sex offenders only to treatment, not detention. Over time, however, the program grew more restrictive, requiring most men to live in halfway houses and boarding homes under contract with the state. By 2014, the private prison companies that ran the homes, such as Avalon Correctional Services and GEO Group, were demanding more money, which Texas didn’t want to pay. The agency in charge of the program, the bluntly titled Office of Violent Sex Offender Management, infuriated Houston-area lawmakers when it was caught moving dozens of sex offenders into the city’s Acres Homes neighborhood without telling local officials. A secret plan to build a for-profit prison camp to house the men in Liberty County similarly collapsed.

Going into the 2015 legislative session, experts questioned whether Texas-style civil commitment was even constitutional after investigations by the Houston Chronicle revealed that roughly half the men in the program cycled back into prison for minor rules violations. Not a single offender had ever graduated from treatment in the history of the program. Nobody under civil commitment had ever been charged with committing another sexually violent act.

Senator John Whitmire, the Houston Democrat who co-authored Texas’ original civil commitment law, barreled into the 2015 session fuming over what had become of the program. He was hell-bent on major reforms. But some of his colleagues bristled when they learned “reform” meant not only a complete overhaul of the state agency that had botched the program — including a new name, the Texas Civil Commitment Office (TCCO) — but also a doubling of its budget. Whitmire told them it was necessary to fix a program that was “broken beyond anyone’s imagination.”

The law Whitmire authored that session, Senate Bill 746, turned Texas’ program from an outpatient model into something more fuzzy — a “tiered” treatment program that began with offenders in a “total confinement facility” and ended, theoretically at least, where Texas began its civil commitment experiment in 1999: with an outpatient treatment program in which patients were allowed to live in the community. The law also directed the agency to “operate, or contract to operate,” at least one facility for the new program.

In June 2015, Governor Greg Abbott signed the reforms into law. The following month, after a request for bids to open a new secure treatment facility, TCCO’s governor-appointed board of directors gave the agency the thumbs-up to negotiate a contract with Correct Care Solutions.

In a prepared statement, TCCO executive director Marsha McLane said her staff visited “over 130 potential locations for housing our clients,” including the Bill W. Clayton Detention Center in Littlefield. “I was invited by the City Manager. Correct Care was the only qualified, responsive bid received.”

It’s unclear how much the agency knew, or cared, about Correct Care’s history. The company was birthed from private prison company spinoffs and subsidiaries that have over the past decade been accused of everything from leaving a Florida psychiatric hospital patient in a scalding hot bath until he boiled alive to providing such abysmal medical care at a West Texas immigrant detention center that inmates rioted. (McLane refused several requests for an interview.)

On July 31, the state awarded Correct Care a $24 million contract to run the Texas Civil Commitment Center. About a week later, Correct Care entered into a lease agreement with the city of Littlefield, where officials were desperate to fill their long-vacant prison with just about anyone — even hundreds of sex offenders.

Today, about 20 states can detain certain sex offenders for what they may do in the future, sometimes indefinitely.

While the state calls the Texas Civil Commitment Center a treatment facility, men inside the lockup claim the therapy there ranges from chaotic to nonexistent. They contend that lapses in treatment, which they say stem from near-constant staff turnover, have made it virtually impossible to graduate from the program. In letters from inside, some of the men say they’ve had up to six therapists since arriving in Littlefield and claim their treatment starts back at square one each time they get a new one. Individual counseling sessions have gone from once every two weeks to once every three months, they say.

“To be constitutional, this has to be a therapeutic program,” said Scott Pawgan, a Conroe attorney who represents a man inside the facility. “It’s got to be the worst therapeutic program in the history of sex offender treatment, far and away.”

Records show that the vast majority of the 139 workers who have left the old prison since it reopened in September 2015 resigned, including eight clinical therapists whose jobs were to provide treatment for men at the facility. (Two other therapists were fired.) Those records also show the state has fined Correct Care, or “adjusted” its payments by, at least $297,000 since the company took over the program.

Correct Care didn’t respond to many of my specific questions about the lockup, nor would it provide anyone for an interview, instead issuing a prepared statement. “Since the initial compliance reviews, the facility has intensified its efforts to comply with all applicable standards and regulations,” Correct Care spokesperson Jim Cheney said in the statement. “We believe that we have made significant progress in correcting more of the items noted in the compliance reports and we work hard to continuously improve our processes and the outcomes for our residents.”

TCCO general counsel Jessica Marsh, the only official at the agency who would grant me an interview, insists the program has moved past its problems, saying, “We’ve worked really hard to rectify those issues, and at this point treatment is going really, really well.”

In the summer of 2015, when Rachel heard that Littlefield was going to reopen its prison, she immediately wanted a job there.

Decent-paying work is hard to find in Littlefield. “There’s just not much here besides convenience stores and little minimum-wage stuff,” she told me. Though there isn’t a bar in town, there’s a liquor store across the street from two other beer and wine shops, all clustered around a single block. The name of Littlefield’s most famous native son, Waylon Jennings, adorns street signs, faded murals and a water tower that overlooks the town’s main drag, which is pockmarked with vacant and half boarded-up storefronts where pigeons roost.

A licensed vocational nurse, Rachel applied for a job as a “therapeutic security technician” at the center. (Rachel asked that I use a pseudonym for this story out of fear she might otherwise never find work in town again.) She thought the feds were going to house immigrant families at the detention center, or at least that was the rumor at the time.

It was during her job interview that Rachel instead learned she’d be working with sex offenders. She took the job anyway. On the first day, she says, security made sure everyone knew they’d be watching the state’s most violent and dangerous sexual predators. “They told us these guys are violent, that they will snatch you up and try to rape you,” she recalled. “We were all fucking scared from Day One.”

Rachel says she quit a year and a half later, not because she was sick of working with sex offenders but because she was appalled by the conditions inside the lockup, particularly the poor medical care. “People were not getting the treatment they needed,” she told me. “A lot of these guys were really old. The clinic was always running out of medications or never had the right ones. It was all very unorganized.”

Like many small towns in the 1990s, Littlefield thought prison-building would bring the kind of jobs needed to prevent young people from moving away. Many rural towns or counties took on public debt to fund the building of prisons to be operated by for-profit companies, which would then contract with other government agencies to house their inmates. A full prison meant revenue to both pay down the debt and fill the company and local government coffers.

In December 1999, Littlefield City Council approved $11 million in revenue bonds to build a juvenile detention center in a cotton field south of town. They named it the Bill W. Clayton Detention Center after the former Texas House speaker, who grew up in nearby Springlake.

A year later, the Lubbock Avalanche-Journal declared the project a “fiasco.” The city fired Texson Management Group, the Austin-based company it had picked to build and operate the detention center, after claiming nearly $2 million had gone unaccounted for during construction. The city took over, borrowed money from the local economic development corporation, and within a year began to consider selling the prison and offloading its failed investment.

“It’s got to be the worst therapeutic program in the history of sex offender treatment, far and away.”

But in 2000, the city found another company to run the facility, a Florida prison firm called Correctional Services Corp. In 2005, GEO Group, one of the pioneers of the private prison industry, bought Correctional Services and began courting other states to send their adult inmates to Littlefield, which in the end only brought more trouble. In 2008, a prisoner from Idaho committed suicide after spending a year in solitary confinement at the facility. Idaho’s prison director accused GEO Group of falsifying reports to cover up problems that stemmed from chronic understaffing and pulled some 300 inmates out of Littlefield.

By that point, budget-strapped states were starting to cut prison spending; Texas, for example, has shuttered eight prisons in the past six years. With the market about to dry up, GEO Group abruptly left Littlefield in 2009 and went on to pursue more lucrative and growing slices of the private prison pie, especially immigrant detention. The city, saddled with debt from building the prison, struggled to find another tenant to take it over. Littlefield raised sewer and water fees, laid off city workers and even passed a new half-cent sales tax to keep from defaulting. In 2011, Littlefield tried to auction the empty prison at a fire sale price that still would have left the city millions of dollars in the red. There were no takers. City financial statements also show that for years Littlefield officials tried to get the feds to house immigrants at the prison, but those talks went nowhere.

“We run around a $6 million budget,” said Littlefield Mayor Eric Turpen. “When the facility went dark, servicing the debt was a huge strain on our financials. It wound up absorbing something like 16 percent of our annual budget by the end.”

That all changed in the summer of 2015, when Littlefield became the solution to Texas’ sex offender housing crisis. Turpen admits it took a little convincing for some citizens to “reach a comfort level” with the new clientele, but he says most citizens agreed the city was better off with a facility that was full.

Texas picked Correct Care Solutions to run the lockup not long after the company acquired GEO Care, a subsidiary of the GEO Group with its own scandal-plagued track record in Texas. The for-profit prison contractor had suffered a series of setbacks in Texas before the quick reshuffling of the state’s civil commitment program resulted in a multimillion dollar contract.

“People were not getting the treatment they needed.”

In 2012, the company, then GEO Care, came under fire for its management of the Montgomery County Mental Health Treatment Facility, Texas’ first foray into publicly funded, privately run psych hospitals. Within months of opening, state monitors described the therapy programs at the Montgomery County facility as “bedlam” and levied tens of thousands of dollars in fines against the company. Staffers reportedly forced one patient to clean up his own feces and urine. Another was left in an isolation cell for four hours while he banged his head on the windows and walls.

That may help explain why the company failed in its attempts to privatize two state psychiatric hospitals in Texas. In 2012, Texas health officials rejected GEO Care’s bid to take over the Kerrville State Hospital, saying the company’s cost-saving staffing plan would have put patients and workers at risk. In 2015, the state killed a tentative deal to turn the Terrell State Hospital over to the company, now Correct Care, months before the state awarded it the civil commitment contract.

Correct Care also runs civil commitment centers in Florida and in South Carolina, where the state’s department of mental health recently contracted with the company to build a new $36.5 million 268-bed civil commitment facility by the end of 2018.

It’s easy to see why civil commitment may be a lucrative, growing market for companies like Correct Care in states willing to privatize their programs. In a presentation to the Texas House Corrections Committee in February 2017, the Texas Civil Commitment Office predicted it will run out of bed space at the Littlefield lockup by 2019 and either have to expand the facility or build a second one. South Carolina’s state director of mental health put it this way in a Powerpoint presentation last year: “More residents enter the program than leave, resulting in continuous program expansion.”

Cate Graziani, a researcher with Grassroots Leadership who tracks the private prison industry’s movement into treatment and civil commitment programs, says the Littlefield contract felt like a “consolation prize” after Correct Care failed for several years to privatize another state hospital.

“We had just told the state all about this company’s track record of serious problems, and then we turn around and they’re putting people in Littlefield months later,” she said.

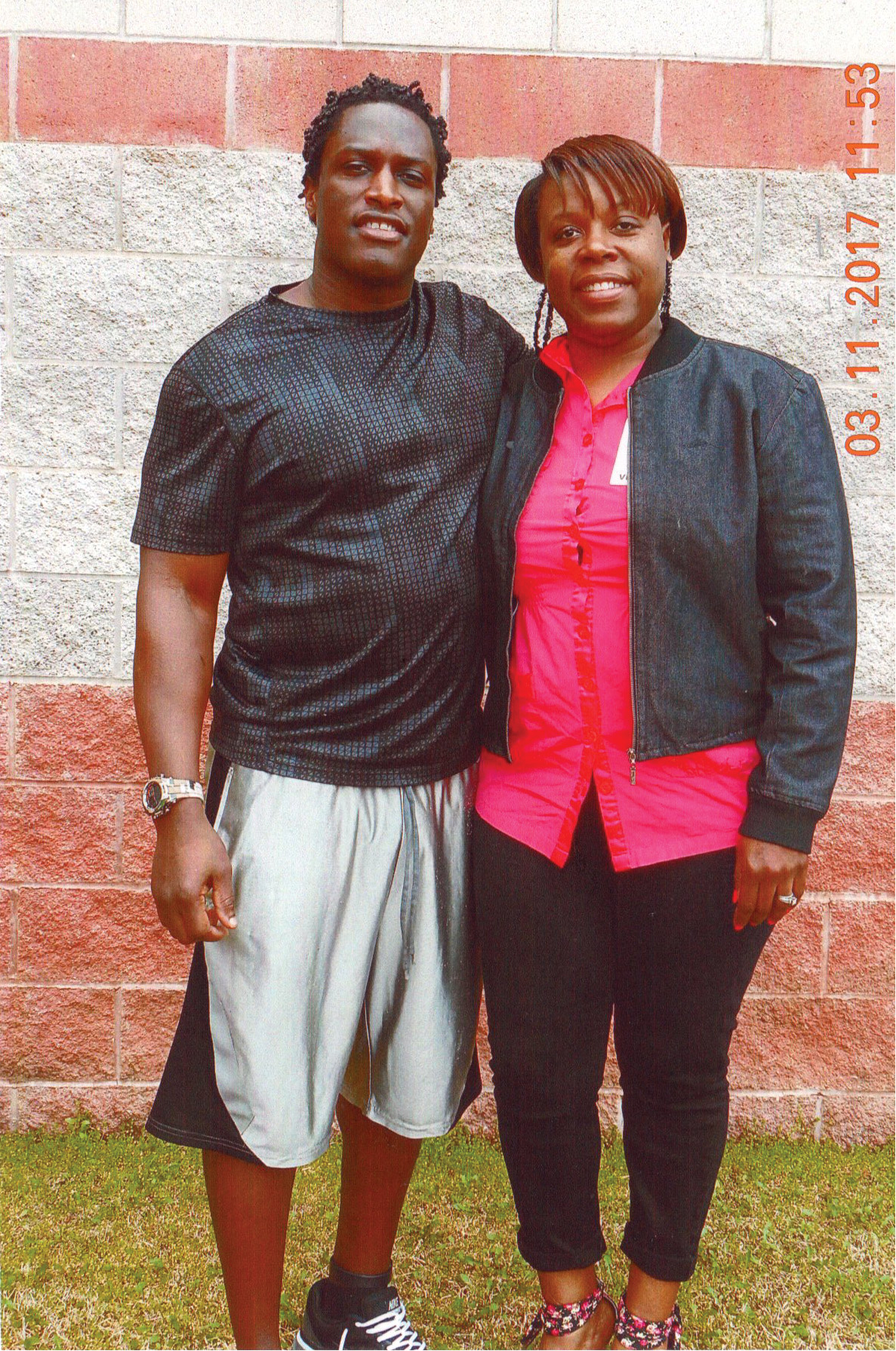

By March, Nicoya Waits had finally saved up enough money for the 1,122-mile round trip from her home in Houston to Littlefield. She timed the trip so she could tell her brother happy birthday in person.

Texas prison officials flagged Waits’ brother, Andre Johnson, for civil commitment as he finished his 24-year prison sentence for raping four Houston women when he was 15 and 16 years old. In 2014, a jury trial in civil court ordered him into outpatient treatment and monitoring at a Dallas-area halfway house. In 2015, the program shifted beneath his feet and by September that year, Johnson arrived in Littlefield with the first wave of civil commitment detainees.

Waits says it was a lot like visiting her brother in prison. “I walk up to a fence, I have to get buzzed in, get scanned and searched and go through correctional officers asking me a bunch of questions, locking big heavy doors everywhere we go,” she recalls. “We sit in a visitation room where somebody is monitoring us, both physically in the room and on video. It didn’t feel like an outpatient facility. It felt just like a prison.”

Bill Marshall, an attorney who represents several men inside, argues that Texas’ civil commitment program drifted even further into a legal gray area after lawmakers reformed it. Texas has joined other states with lockdown-style civil commitment programs that have been challenged in court in recent years. In 2015, the year Abbott signed the new program into law, judges in Missouri and Minnesota ruled those states’ programs unconstitutional because they appeared designed to keep people behind bars indefinitely. The Minnesota judge called the state’s program, which hadn’t discharged any offenders in its more than 20-year history, “punitive” and lacking the “safeguards of the criminal justice system.”

In late 2015, for the first time ever, a visiting state district court judge in Conroe freed an offender, Alonzo May, a 58-year-old Dallas man, from Texas’ civil commitment program, ruling that the state couldn’t legally send people with outpatient commitment orders into an inpatient program housed out of the Littlefield lockup. Days later, a state appeals court in Beaumont overturned the ruling and sent May to Littlefield.

“If their judgment says they need to be in outpatient treatment, how can you justify putting them in a repurposed private prison if they haven’t done anything else wrong?” said Marshall, who represented May.

“We had just told the state all about this company’s track record of serious problems, and then we turn around and they’re putting people in Littlefield months later.”

Melissa Hamilton, a law professor who studies civil commitment, says Texas’ shift to a lockdown facility could render its program more vulnerable to legal challenges. Hamilton, who recently taught at the University of Houston Law Center and is now a senior lecturer at the University of Surrey, says Texas lawmakers made the program even more punitive in 2017 with amendments that allowed guards at the Littlefield lockup to wield pepper spray and batons.

“They’ve made this program look very similar to criminal imprisonment, which is a big red flag,” Hamilton said.

Hamilton says a series of recent lower-court cases show judges are becoming more skeptical not only of the way states handle civil commitment but also toward other restrictions placed on sex offenders after they’ve served their sentences. A shoddy or haphazard treatment program for sex offenders in detention could be ammunition for the kind of lawsuit that some of the men in Littlefield have already begun filing, she says. Problems at the Littlefield facility could “undermine the argument that the state is serious about treatment,” Hamilton told me.

John says he’s seen his friend Jason Schoenfeld trade the fear of getting sent back to prison under the old program for the kind of malaise that accompanies a sentence without an end date. He’s currently on the program’s next-to-lowest rung on the treatment ladder. John says that for the past two years he has asked the state for approval to bring Schoenfeld to his church, where, he says, members already know of his previous crime and welcome his visit nonetheless.

“Look, I’m not a cheerleader for sex offenders or anything, but I hate injustice,” John told me while sitting in his hotel room in Littlefield. “He went through the justice system, he served the sentence that the system decided to give him.”

John and his wife lined up at the gate in front of the Texas Civil Commitment Center early one morning in December. They try to make the five-hour drive to visit Schoenfeld at least once a month. He says he has asked TCCO and Correct Care whether Schoenfeld can someday move to his ranch.

“I get back no response whatsoever from them,” John told me. “Apparently where he’ll live if he ever gets out is not even on their agenda right now.”

Elena Mejía Lutz contributed to this story.