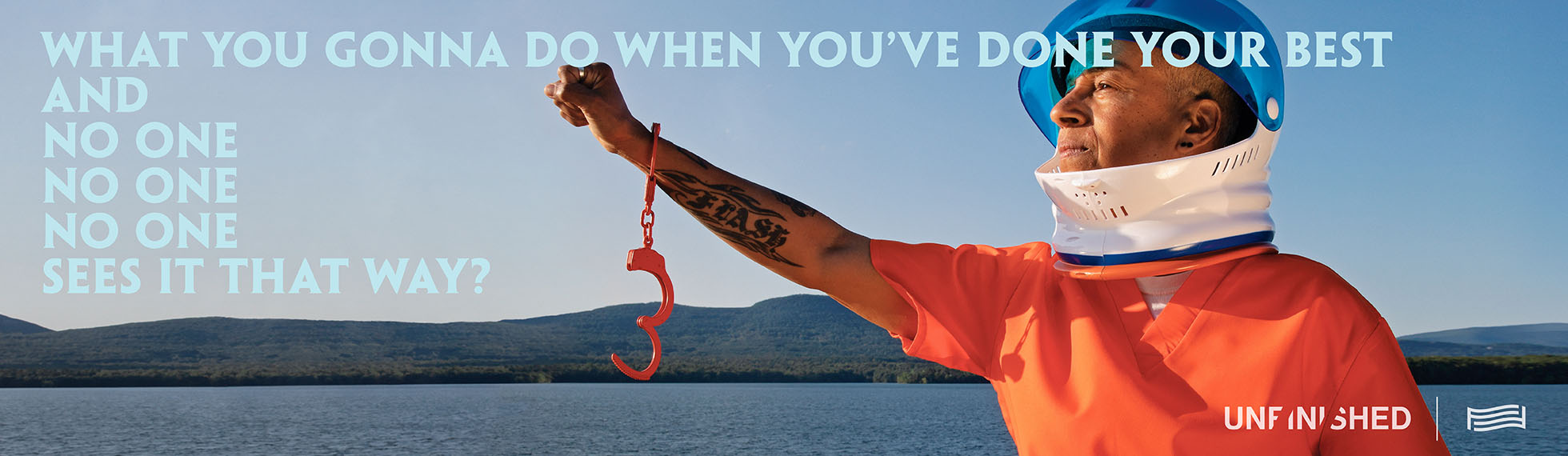

A Strange and Wonderful New Book Celebrates the Often-Ignored Work of Outsider Artists

The 11 short biographies included in the book — largely tales of suffering, redemption and mystery — are told with great sensitivity and warmth.

In 1967, more than 40 years after his death, Charles Dellschau’s belongings were finally piled out on the street in front of his former house in Houston. An antiques dealer was making a routine visit to inspect the junk when a stack of 12 large notebooks caught his eye. Each was “handbound with shoelaces and thick with text and colorfully detailed mechanical drawings of dirigible-like machines.” The dealer found a place for the notebooks in his store, and they eventually made their way to the queen of the Houston art world, Dominique de Menil.

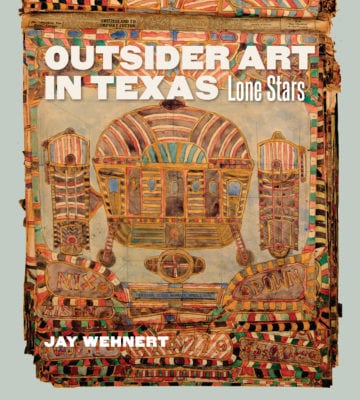

Intrigued by Dellschau’s elaborate drawings and otherworldly writings about fanciful flying machines and the secret society that created them, de Menil bought four of the notebooks. Dellschau was on his way to posthumous art glory — at least within the obscure realm of outsider art. This is the world that Jay Wehnert chronicles in his strange and wonderful new book, Outsider Art in Texas.

by Jay Wehnert

Texas A&M University Press

$40; 132 pages

In 2015, the New York Times called Dellschau a “visionary,” and the following year a page from one of his notebooks sold for more than $22,000. But there’s little reason to believe that the deeply isolated man would’ve cared for this recognition. He created his notebooks over a period of decades after he retreated from the world following several family tragedies. He worked in utter solitude. Did he intend the stories and drawings as science fiction, or was he depicting scenes from a mind colored by mental illness? As Wehnert puts it, all we can know is that Dellschau’s life was “shrouded in mystery and wonder.”

Dellschau’s story is one of 11 featured in the book. Short biographies of these little-known Texas artists are accompanied by 68 color reproductions of their work. Wehnert is a collector of outsider art and director of Intuitive Eye, an organization dedicated to studying self-taught artists. He tells their stories — largely tales of suffering, redemption and mystery — with great sensitivity and warmth.

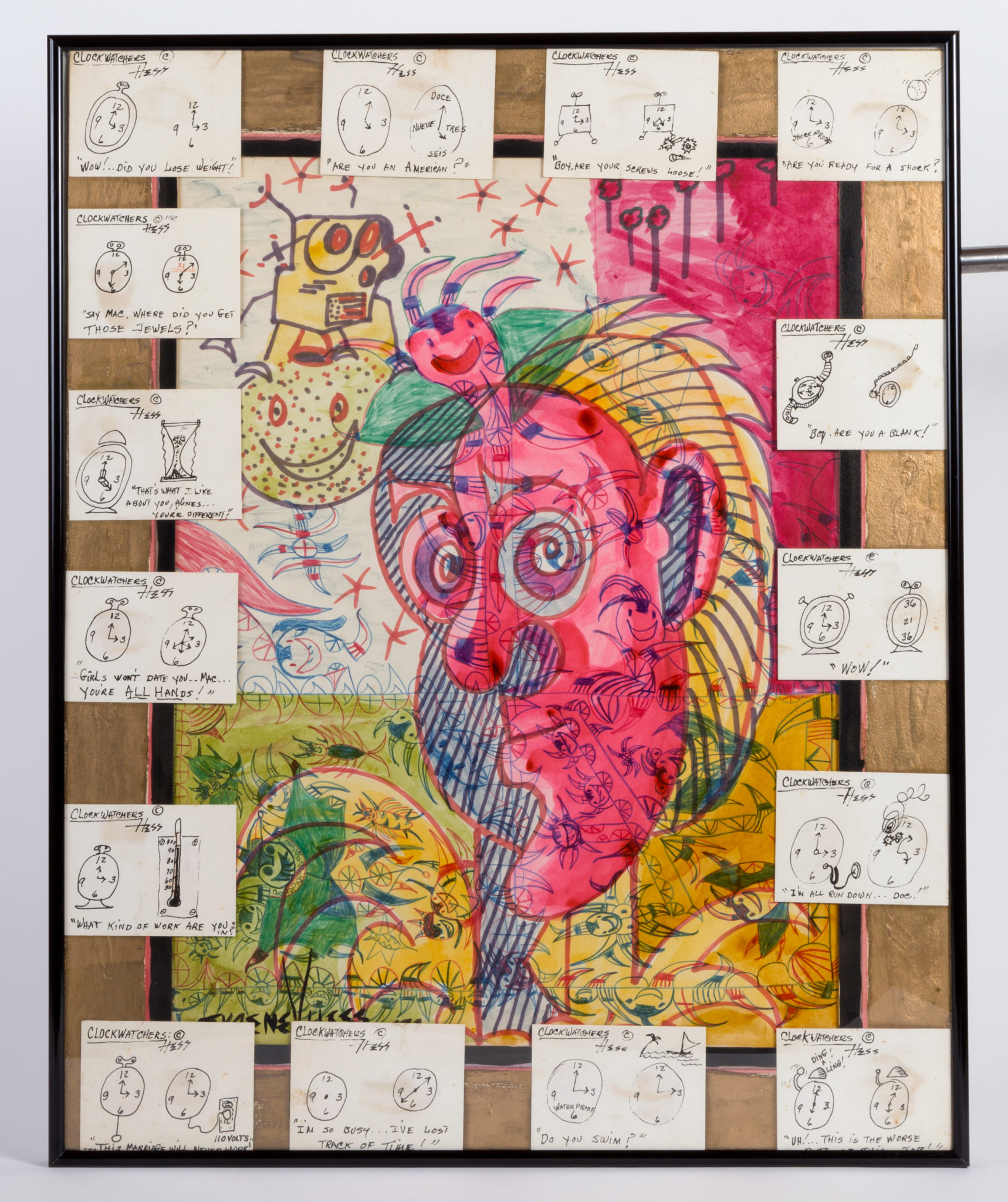

The book’s introduction elaborates on the ideas of French artist Jean Dubuffet, who initially described the self-taught artist concept as art brut, or raw art. Dubuffet wasn’t the first to take note of the art produced in the mental hospitals of Europe, but as a renowned artist himself he was able to speak authoritatively to its quality, even professing to find more merit in “raw art” than in the “cooked” art culturel.

“Through these artists that were so … isolated and estranged from the world,” Wehnert writes, “[Dubuffet] saw transcendent art that arose from a true human spirit of creativity.”

Wehnert returns to Dubuffet’s concepts several times, focusing on the profound isolation these Texas artists experienced, either because of mental illness, homelessness, personal tragedies or the crippling racism that the predominately African-American men profiled here experienced. He then shows how the art they created did, in fact, transcend the hardships of their lives.

Frank Jones (1900-1969) was born in the East Texas town of Clarksville with a caul over one eye; local lore held that this allowed him to see into the spirit world. Sure enough, as a boy Jones claimed that he saw and heard from frightening spirits. He was convicted of the murder of an extended family member. In prison (where he was a model prisoner), Dellschau began drawing “devil houses,” two-dimensional structures that gave “form to the ethereal spirit world in which he lived.” Like other artists, Jones was discovered while in prison and given gallery shows, even before the concept of outsider art was fully established.

Wehnert met one of these artists, Richard Gordon Kendall, a homeless man who drew almost professional-looking sketches of prominent Houston buildings on whatever scraps of paper he could find. Kendall is among the most mysterious of the book’s subjects, as he simply disappeared rather than be “discovered.”

What did these painstakingly created architectural drawings mean to a homeless man? Wehnert provides a plausible explanation. Kendall drew his buildings in isolation, not showing their surroundings, and Wehnert muses, “It is not a great leap to interpret the buildings as … aspects of … Kendall himself — alone, separated from those around him, isolated.” That may sound grim, but Wehnert goes on. “His capacity to relate to his environment through his creativity is almost palpable,” lending a warmth and personal feel to the drawings.

Movingly, Wehnert writes that since he last met Kendall in 1998, “I continue to look for him out of the corner of my eye as I travel through downtown Houston.” It’s appropriate that this compelling, beautifully illustrated book end on that note of mystery and loss.