Above the Law

Pamela Elliott was the new sheriff in town. But instead of law and order, she brought chaos.

A version of this story ran in the May 2016 issue.

The first thing she noticed was Sheriff Pamela Elliott standing across the street. It was an August evening in 2014, and Rachel Gallegos had just gotten home for a meeting of the Edwards County Democratic Party. The law enforcement official was a highly unlikely candidate for a session with local Democrats. Edwards County — Rocksprings is the county seat — is solidly Republican, and Elliott is militantly conservative.

There were cars everywhere — on the street, blocking the road, even parked in Gallegos’ yard, about 30 people in all. “They were the sheriff’s staff — some in plain clothes, some in uniform,” Gallegos recalls. “There were dispatchers, jailers, friends, supporters — anyone, it seemed, that Sheriff Elliott could gather up.”

Ten minutes after the start of the meeting, all four of the executive committee members in Gallegos’ house were gabbing about the posse amassed outside. Then there was a loud knock at the door — Sheriff Elliott. “She came to the door in uniform and was about to come in, so I held the door and said, ‘May I help you?’” Gallegos says.

According to Gallegos, Elliott said she had a right to attend the meeting and that she’d received permission from the Texas attorney general to be there under the Open Meetings Act. “She held her boot in the door and I told her to have him call me — that if he said she could be there I’d let her in,” Gallegos says. “And nobody ever called me, of course.”

Caroline Ramirez, who dropped her husband off at the meeting, described the crowd outside as an “angry mob.” Later, she would state in a written complaint submitted to the attorney general, the secretary of state and the district attorney that she “was shocked that [Elliott] was in uniform but wasn’t doing anything to control the crowd, keep the peace, or protect them or us. She seemed to be encouraging the mob. I wanted to call someone, but I had no idea who I should call if the head of our law enforcement is part of the problem.”

In her own complaint, Gallegos wrote, “I can no longer assume that our Sheriff and her department will act as Peace Officers. I need some guidance as to how to protect myself.”

A month later, she received an email from Timothy Juro, an attorney in the Texas Secretary of State’s office. He confirmed that a meeting of the local party’s executive committee would not fall under the Open Meetings Act.

Gallegos believes Elliott’s sole purpose was to intimidate Democratic voters in an upcoming election for Edwards County judge. Souli Shanklin, a Republican, was Elliott’s ally, and Ricky Martinez, the Democrat, was expected to do well. Gallegos says law enforcement outside her house could have influenced the vote by making people in town think the Democrats were up to no good, or even doing something illegal. Martinez ended up losing, with 46 percent of the vote.

Andrew Barnebey, the former chair of the Edwards County Democratic Party and current county commissioner, likewise sees ulterior motives. He said it was “ridiculous” for Elliott, a Republican, and her allies to believe they had a legal right to attend a Democratic Party meeting in a private home. Equally absurd, he said, is the idea that “these folks would want to barge in to listen to this little bit of housekeeping.”

Buck Wood, an Austin attorney who has practiced election law in Texas for 45 years, says it amounts to harassment. “It’s intimidation and illegal use of the sheriff ’s office powers,” he says. “It sounds like somebody needs to bring a lawsuit, because she sounds like she’s totally out of control. It may even be abuse of office, and if so, could be a criminal offense.”

Republican Party County Chairwoman Kathy Walker told the Observer that she believed the Democrats in Edwards County had an “open door policy” for their meetings. “Why would they have it in a private home? We have our meetings at the women’s club.”

In any case, the Democrats didn’t launch any legal action against the sheriff’s office, and Elliott never apologized. Instead, the strange showdown became another in a long list of Elliott power plays that have plunged this isolated county into political turmoil. Her detractors say that since her election as sheriff in 2012, she’s waged an aggressive campaign to intimidate Democrats, voters and the Latino community.

The sheriff has arrested elected officials and gone to war with the superintendent. Her office has accused voters of electoral fraud with little evidence. And while embroiled in political combat, she’s been accused of bungling an investigation into a high profile murder case — one that’s haunted Rocksprings for 20 years. Elliott appears to be motivated in part by a growing far-right movement that exalts sheriffs as the last line of defense against a tyrannical federal government.

Elliott said she would answer questions via email, but then never responded.

Conflicts between the so-called patriot movement and the federal government have grown in recent years. High-profile incidents like the Bundy standoff in Nevada or the occupation of the Oregon wildlife refuge dominate headlines. But most anti-government activists don’t carry a badge and a gun or spend their days in local communities, ostensibly serving and protecting their neighbors.

![]()

Elliott grew up in Silsbee, a town Just north of Beaumont in southeast Texas. She joined the Army in 1989 (later deploying to Afghanistan), and served with the Gilbert Police Department in Maricopa County, Arizona, the stomping ground of Sheriff Joe Arpaio, who famously forced inmates to wear pink underwear, reinstated chain gangs and, according to the U.S. Department of Justice, oversaw the worst pattern of racial profiling in U.S. history.

She later joined the Beaumont Police Department, but moved to Rocksprings with her husband, Jon, and their three children in 2008 to open a game ranch, which they named Bownanza. A former employee who didn’t want to be named said Elliott told him she wanted to retire from law enforcement, but was lured to join the Edwards County Sheriff’s Office by then-Sheriff Donald Letsinger. The hunting business didn’t last long, however — the employee says it closed down at the end of 2009 — and now Jon works as a real estate agent and runs a gun shop, Down Range Supply.

Elliott joined the Edwards County Sheriff’s Office as a reserve deputy in November 2008, according to her Facebook page, serving under Letsinger, but when her predecessor decided not to run for office again, she went for the top job.

She’s a member of the Constitutional Sheriffs and Peace Officers Association, which Sheriff Arpaio founded with former Graham County, Arizona, Sheriff Richard Mack, a minor celebrity on the far right. The association encourages its members to disobey laws they view as violating the Constitution. Mack is a champion of the right-wing “patriot movement” that embraces civilian militias, anti-government rhetoric, conspiracy theories and Christian end-times theology.

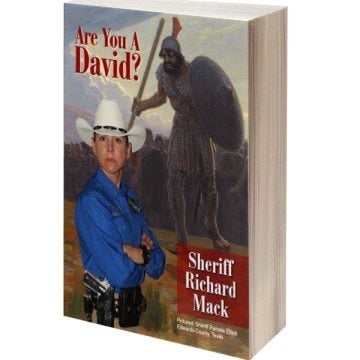

Mack has authored four books, including The County Sheriff: America’s Last Hope and Are You A David? which was published in 2014 and features Elliott on the cover. “Just when we have begun to despair,” Mack writes in the preface, “state and local officials have made moves to nullify unconstitutional acts of the Federal Government.”

A 2012 report published by the Southern Poverty Law Center (SPLC) said Mack was “spreading anti-government ‘Patriot’ ideology to the Tea Parties, enthusiasts of the Second Amendment and, above all, law enforcement officials.” A year later, an SPLC report said Mack was proselytizing “county sheriff supremacy … the idea that sheriffs are the highest law enforcement authority.”

During the infamous Bundy standoff in Nevada over grazing fees on federal land, an Edwards County militia leader, Rick Light, wrote on an online message board that he and Elliott “put out a standby order for volunteers” in order to support the Nevadan in case the proverbial shit hit the fan.

Elliott also seems to be a regular at open carry demonstrations. At one, in June 2014 in Howard County, she rambled on about how she wanted to show then-Attorney General Eric Holder “how to be a real law enforcement officer and how to make arrests.” At another during the same month, she said it was an “absolute must” for anyone entering her county to refrain from shooting a woman. “Except for a few [women],” she added. “We’re going to put them on a list.”

In any other town, residents may have taken her statement as a joke. Not in Rocksprings, where paranoia has become part of the community’s fabric. Rachel Gallegos told me she’d like to see a copy of that list, “because I’m pretty sure I’m on it.”

![]()

To drive the countryside around Edwards County is to appreciate just how vast West Texas really is. Edwards County has almost exactly as many square miles as it does people. Bulls graze by the fence lines of vast ranches with names like Buck Ass Ranch and Wa To Go Whitetails & Exotics. There’s a lot of room for mischief out here.

One afternoon in March, I drove to a spacious ranch house a few miles outside of Rocksprings that more than one person has described as a “safe house.” Much of the Rocksprings establishment was gathered in the living room, including the school superintendent, a former mayor and the current mayor — not the kind of folks who typically fear law enforcement. A plate of toast with cream cheese on the counter sat untouched. Every one of the eight people gathered says they are worried that if they talk to me, there will be repercussions from the sheriff’s department.

“I’ve been told to install a camera in my vehicle just in case something happens,” says one man, who didn’t want to be named. “People here, officials included, are very wary of the sheriff.”

Most do not allow me to use their names. David Velky, a serious-looking man in his 50s, is an exception. He says he’s been in the “school business” for 25 years as a teacher, a principal, and now as superintendent of Rocksprings ISD, a position he’s held for five years. Before he came, there were financial difficulties, academic issues and discipline problems, and Velky says he’s worked hard to resolve them.

Velky arrived in Rocksprings in 2011, a year before Elliott was elected sheriff. After she took the office, he says, she immediately sought a meeting to ensure that he was connected with the juvenile probation authorities. Velky wasn’t used to law enforcement interest in discipline within the school system. “You’ve usually got to beg the police to come up to the school, and here I have them trying to push their way in, so that made me a little bit uncomfortable,” he says.

It didn’t take long, Velky says, for Elliott to “take an intense disliking to me.” The long-running spat between Velky and Elliott even reached San Antonio when News 4 ran a segment, calling it a “he said, she said battle of words.” One disagreement centered on some furniture a teacher had apparently taken from the school. Velky said it was stolen; Elliott refused to file criminal charges because she said the furniture was “placed in the trash and [the teacher] retrieved it.”

In another, Velky accused Elliott of making disparaging remarks about school board members — a claim she denied. Elliott said she received complaints from six district employees claiming Velky was intimidating them, which he says is untrue.

Velky tells me that not long ago, two members of the school board — his bosses — were driving through town when Elliott flagged them down, telling them they needed to vote against the renewal of his contract. “This is while she’s in uniform,” he says. “I try not to be a conspiracy theorist, but I concluded this person either has some innate dislike for me or mistrust.”

On another occasion, Velky says, Elliott told him “that one of my board members was bad and it didn’t matter how much holy water I put on them.” She was referring, he says, to his preparation at the time to become a deacon in his local Catholic church. “I’d not encountered anything like that before,” he says.

The sheriff’s militia connection scares him. At one school board meeting he looked out into the audience and noticed Rick Light, the leader of a Rocksprings militia called the Edwards Plateau Rangers. “I immediately felt somewhat threatened,” he tells me. “I didn’t know whether there would be a physical altercation — he didn’t have his uniform on — but it was a big question mark.

“I believe the plan is to get rid of me and certain board members in order to take control of the school. I think they want control over the hiring of the teachers and staff members. I think they want to be able to bypass the procedural safeguards of the law — to arrest people without the grand jury; to bring charges without consulting the district attorney; to decide who is on the grand jury.”

Gallegos, a fourth-generation Rocksprings native who served as mayor from 2005 to 2009, says she first clashed with Elliott shortly after stepping down as mayor. She says that in August 2009, Elliott, then a deputy with the sheriff’s office, came to Gallegos’ office at the phone company where she works. Elliott told her she had information that when Gallegos was mayor she had been lowering the sewer rates for her friends and family.

“She mentioned the name Jane Bean, but I told her she wasn’t a friend or family member,” Gallegos says. “Mrs. Bean was an elderly lady who had been charged $200 a month for sewer and it should have been $20. I told the sheriff we had changed that and that we documented everything. She said she’d look for others but she never came back.” Besides, Gallegos says, as mayor she wasn’t responsible for billing.

In September, Elliott arrested current mayor Pauline Gonzales for misusing government funds, and she has since been indicted on four counts of official misconduct, including hiring her husband, Ramiro, to work for the city. She claims she’s done nothing wrong, and the case is still working its way through the court system.

Perhaps the most troubling stories involve voter intimidation.

During the 2014 midterm elections, Gallegos was on her way to work when she noticed sheriff’s deputies at the polling site at the Baptist church. “When I got to work, the staff were discussing why there were deputies at all the locations,” Gallegos says. “Not just the church, but the school auditorium, the park building and the Church of Christ as well. So I went to each of them, and they were inside every one.”

Gallegos says the county clerk eventually called the sheriff’s office to tell her to pull her officers out of the polls. It was about 3 p.m. and voting had been underway for hours. She believes Sheriff Elliott was attempting to intimidate Hispanic voters in Edwards County, which in the last 15 years has grown from 45 percent Hispanic to 55 percent.

Gallegos says she spoke to elderly Hispanic friends who didn’t vote because they were scared off. “They just said ‘Oh, they’ll come after me; they’ll go after my children, my grandchildren, it’ll just cause trouble,’” Gallegos says. “The elderly are easily intimidated.”

Romana Bienek, the city secretary who was working at City Hall on the day of the 2014 midterm election, corroborates Gallegos’ account. She says she took nine phone calls from voters intimidated by the presence of sheriff ’s deputies at the polls.

“When I called the sheriff’s office and spoke to the sheriff herself … she said it was really none of [my] business. She told me to write down the people’s names and phone numbers and that she’d talk to them. I said ‘Fine,’ and that was it.”

Bienek says that when she went to vote later that day, the deputy was there “walking around, looking at everything. He wasn’t like a poll-watcher [who] sits in the corner and doesn’t talk. These officers were talking to the people coming in to vote.”

In a phone call in early April, former Sheriff Letsinger, who endorsed Elliott in 2012, told me he wasn’t aware that sheriff’s deputies had been at polling stations in 2014. When I asked if he would have posted his deputies at booths, he replied, “I would not. But maybe [I’d have posted them] down the street if I thought there was going to be some kind of problem. But I don’t think there has ever been any kind of problem.”

Republican chair Walker told me that the vast majority of Texas cities have some kind of security officer present at the polls. “There is no voter intimidation going on whatsoever,” she said. “If you live in a small town, it’s nice to have somebody there — it may be 12 midnight or 1 a.m. when these ladies leave. I’ll admit the sheriff’s office was asked to be there all day, but it wasn’t intimidation. Most of these people know these police officers. They’re their neighbors.”

But Wood, the election law attorney, says law enforcement shouldn’t be anywhere near a polling booth unless there’s trouble or violence. “That’s pure and simple intimidation,” he told me. “Only certain people can be in the boundaries of a polling station: voters and election officials.”

In September, Gallegos’ niece, Reneé Gallegos-Johnson, received a letter from the Edwards County Sheriff’s Office claiming she had voted in Edwards County despite not living there. Signed by Captain Darrell Volkmann, it read: “I have investigated this matter and I have determined that you do not live in Edwards County, as a matter of fact, you do not live in the State of Texas.” Volkmann attached information “concerning Section 64-012 of the Texas Election Code — illegal voting,” which he pointed out was a second-degree felony “for each violation” (italics his). Gallegos-Johnson, 42, moved to Rocksprings with her parents when she was 10 months old, but for the past decade has lived in Louisiana, where she works as an administrative assistant in a real estate office. She owns a home in Rocksprings, visits often and plans to retire there with her husband. She says she contacted her local voter registration office in Louisiana on July 10, 2014, to explain that she wanted to vote in Edwards County. She filled out a registration form in Rocksprings and soon received her voter registration card. She says she did nothing wrong. Wood agrees. He says he hasn’t seen anybody disqualified from voting for not being a resident. “The Texas Supreme Court said if you have presence in an area — some presence in the electoral district — and you have intent to make that your permanent home, then that’s the end of it. Trying to prove somebody doesn’t intend to live there is almost impossible.”

Gallegos-Johnson says she doesn’t think the sheriff likes her family. “I think my last name must have screamed so loudly that I caught her attention,” she says.

She says she spoke to an attorney at the secretary of state’s office in Austin who told her she had not committed any offense. Regardless, Gallegos-Johnson hired a lawyer, who sent a letter to Volkmann explaining as much. She’s heard nothing since. “My attorney says they should have been educated in the law before sending out letters like that,” she says. “I’m a fighter and don’t like to be messed with when I’m in the right. But they could be picking on someone who doesn’t realize their rights have been violated.”

![]()

In 1996, a brutal murder rocked the town: someone stabbed 35-year-old Patricia Paz to death, propped her up in a chair in her living room, then attempted, unsuccessfully, to set fire to her home. In the summer of 2014, the television show Unsolved Mysteries contacted the Edwards County Sheriff’s Office to look into featuring the case.

After hearing about the Unsolved Mysteries inquiry, Elliott asked Volkmann to review the 1996 case, and the following summer they made four arrests, including Paz’s niece and nephew, Angelica and George Torres. But it soon became apparent there were holes in Elliott’s case.

Angelica was only implicated by a jailhouse rumor, and George was named by a jail snitch who claimed he’d heard him brag about the killing. As for the other two suspects, Tina Flores, apparently, had a penchant for applying makeup when she was stoned — in a style that matched Paz’s makeup when she was killed. And Neri Garcia was named by a confidential informant who told Volkmann that Garcia had been smoking crack with George Torres and that they knew Paz had money in her house because she’d cashed a check earlier that day. It was Garcia, the informant said, who actually murdered Paz for the money.

The “evidence” Sheriff Elliott and her deputies claimed to have against these four individuals didn’t stack up.

Crucially, Letsinger, who investigated the murder in the mid-’90s, said neither he nor previous sheriff Warren Guthrie, who was in office when the murder happened, could find any record of a check being cashed.

The most explosive evidence showing that the sheriff’s office had the wrong people was when Neri Garcia’s defense attorney, Patrick O’Fiel, showed that his client was in custody in Kerrville the night of Paz’s murder. O’Fiel claims he informed the sheriff’s department of this fact. “In this situation maybe crime did pay off for him,” O’Fiel tells me one morning by phone from his office in Kerrville.

Elliott claims Garcia escaped from custody that night, and even though there was no check, she insists robbery was the motive.

In September 2015, District Attorney Tonya Ahlschwede, in conjunction with the Texas attorney general, dismissed charges against all four people for lack of probable cause, saying the case needed “further investigation.”

O’Fiel says his client’s false arrest by Elliott in 2015 — nearly 20 years after the murder — is “a civil rights violation.” He adds: “My guy is having trouble getting an apartment now because he has an arrest for capital murder on his record. I think it’s a botched investigation.”

Jay Adams worked for the Edwards County Sheriff ’s Office for decades, first as a deputy, then as chief deputy. He says Elliott has a habit of sending cases to the district attorney without enough information. “That’s why the DA won’t take a lot of her cases — she’s a very intelligent woman and doesn’t want to go to court and have the cases thrown out. It’s just like [the Paz murder]. I read the affidavit and it’s written on an almost eighth-grade level. You can tell it wouldn’t float.”

The Paz murder case bears more than a passing similarity to another controversial case Elliott was involved in as a cop in Gilbert, Arizona. On September 20, 2000, a short Hispanic woman with facial acne held up a Gilbert bank, posing as a customer. Rachel Jernigan suddenly found herself as the prime suspect after a postal worker identified her.

Pamela Elliott (then Pamela Brock) and another officer were assigned to investigate. The bank teller picked out Jernigan from a photo lineup, and Jernigan was charged with that and two other robberies.

But while she was in custody, two more bank robberies were committed by a woman matching Jernigan’s description. More significantly, a fingerprint taken from the teller window didn’t match Jernigan’s. Nonetheless, Jernigan was convicted and sentenced to 14 years in prison. Then, in 2008, Juanita Rodriguez-Gallegos admitted she was responsible for the September 20, 2000, bank robbery for which Jernigan had been sent to prison. The charges against Jernigan were dismissed and she was released. She had spent seven years in prison for a crime she didn’t commit, and in 2012, the federal government settled a wrongful conviction lawsuit for $1 million.

![]()

On a ranch gate a few miles outside of Rocksprings, a sign asks voters to “Re-elect Sheriff Pamela Elliott.” Under a picture of Elliott sporting her trademark cowboy hat and pink shirt, the sign reads: “I will never betray my badge, my integrity, my character, or the public trust. I will always have the courage to hold myself and others accountable for our actions.”

Letsinger insists his successor is beyond reproach. “She’s highly trained, highly educated, and from a military background,” he says. “She’s one of the smartest people I ever met and she was an excellent deputy. I can’t think of anything she’s handled badly. As a matter of fact, I’d highly recommend her, and I intend to vote for her as well.”

But trouble keeps mounting for Elliott. In February, Perry Flippin, a former San Angelo newspaper editor, led a complaint with the Texas Ethics Commission alleging campaign finance violations.

Among other things, the complaint alleges Elliott “accepted campaign contributions and made campaign expenditures,” including to herself, before she had appointed a campaign treasurer — prohibited under the Texas Election Code. The complaint also charges that she took out a “lengthy” political announcement in the Rocksprings Record despite not listing the expenditure in her report, another alleged violation of the code.

What’s more, Elliott now has a Democratic opponent running against her for sheriff in November. Jon Harris is a U.S. Army veteran who moved to Edwards County with his wife, Katherine, in 2014 after working as a canine handler in counter-explosives in Afghanistan and Iraq.

Elliott is vigorously campaigning for re-election. Recently she took out an ad in the local paper. She wanted voters to know something about her: “It’s no secret that I do not conform with any scripted expectations of ‘the political game’ when serving as your Sheriff. I will continue to serve as an Army Reserve Officer, a mother, a sister, a neighbor who is loyal to the Lord in a position that should not be politicized but as so scripted in the bible: ‘Do not pervert justice or show partiality.’”

To support journalism like this, donate to the Texas Observer.