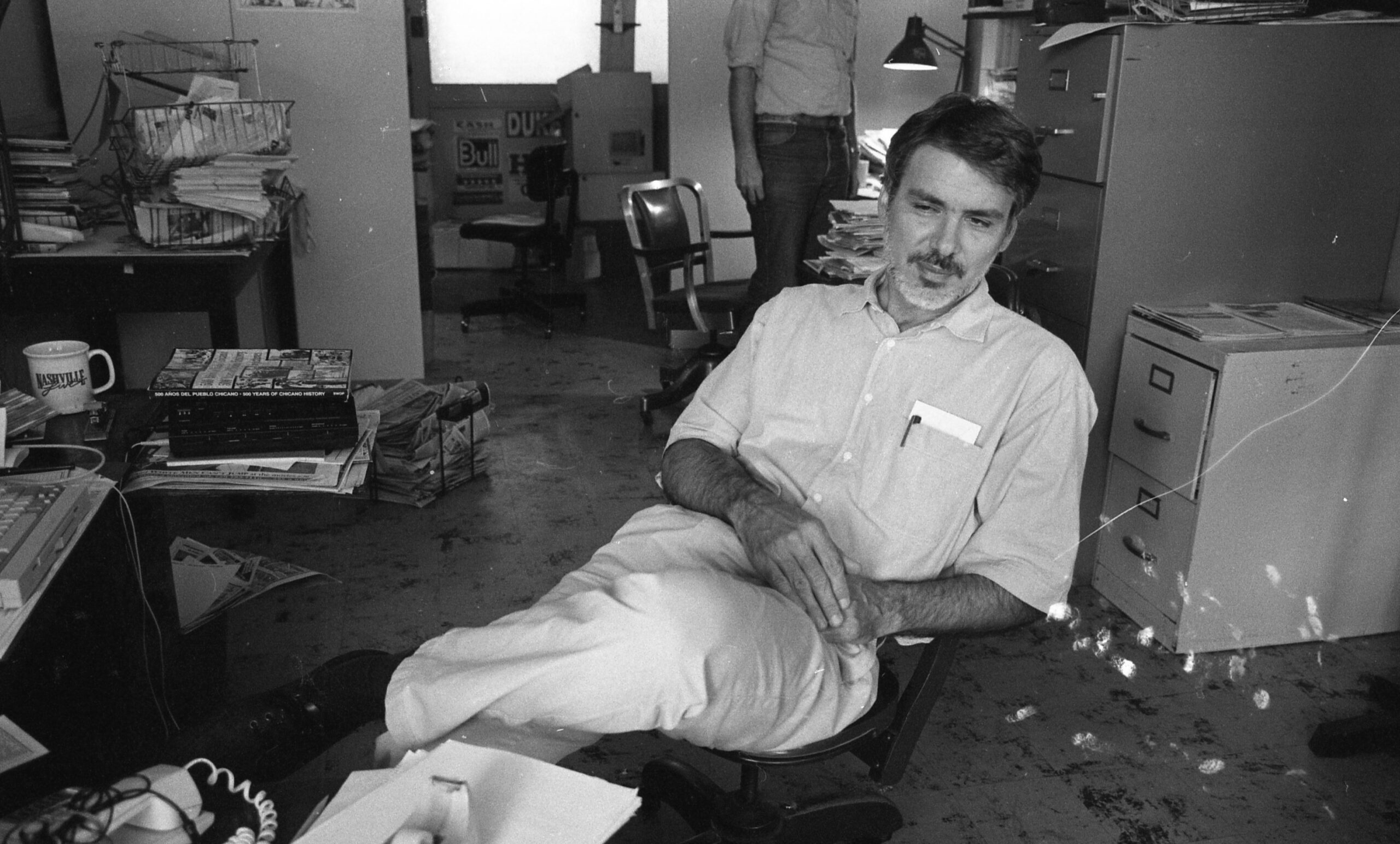

As we at the Texas Observer were racing to finish proofreading of our November/December 70th anniversary issue, I managed to track down Alan Pogue in a back office of the KOOP radio studio off Airport Boulevard in Austin. I was a tad desperate to locate caption information for the images in this photo essay, and, to my relief, there he was copying over handwritten cutlines into an email to me.

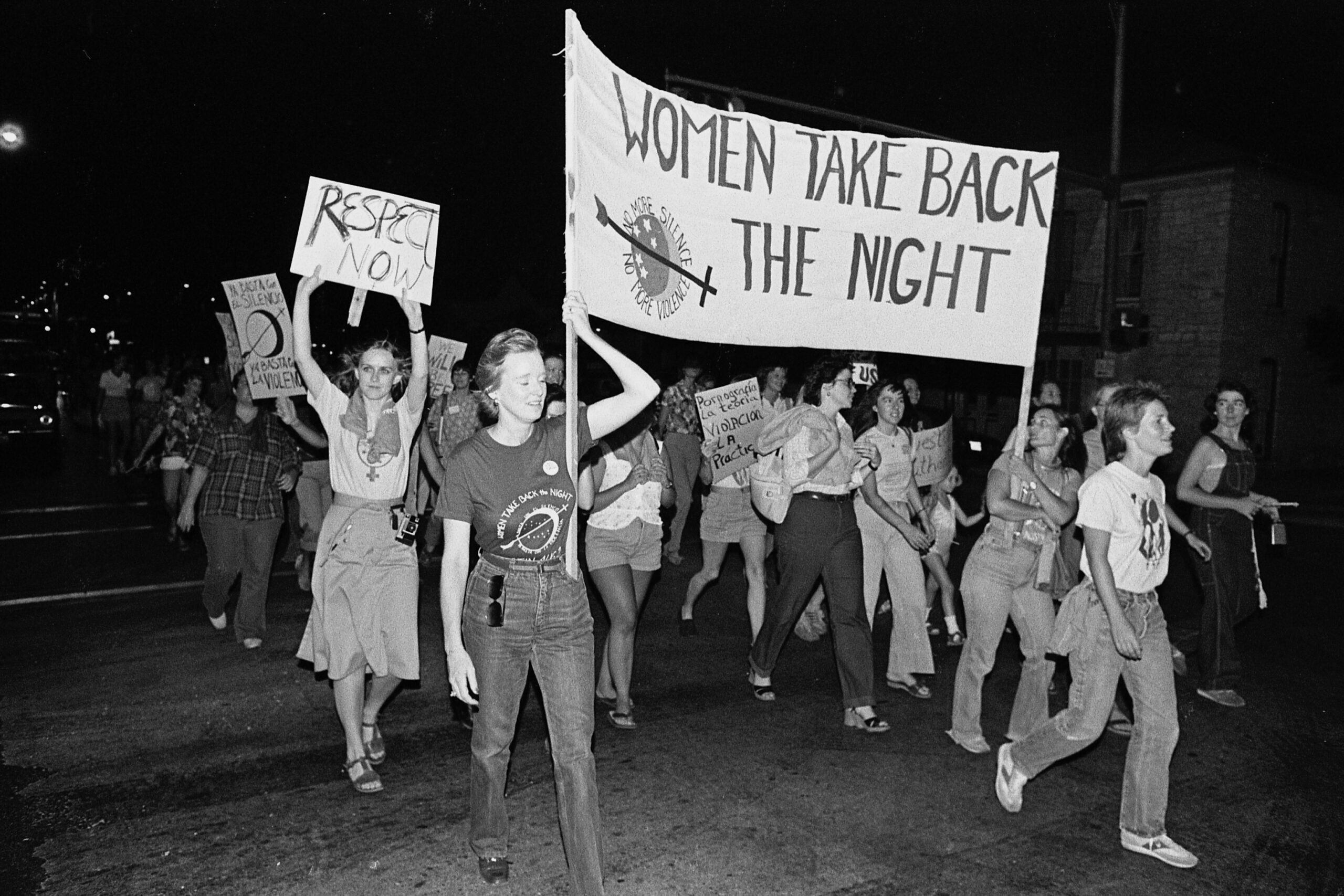

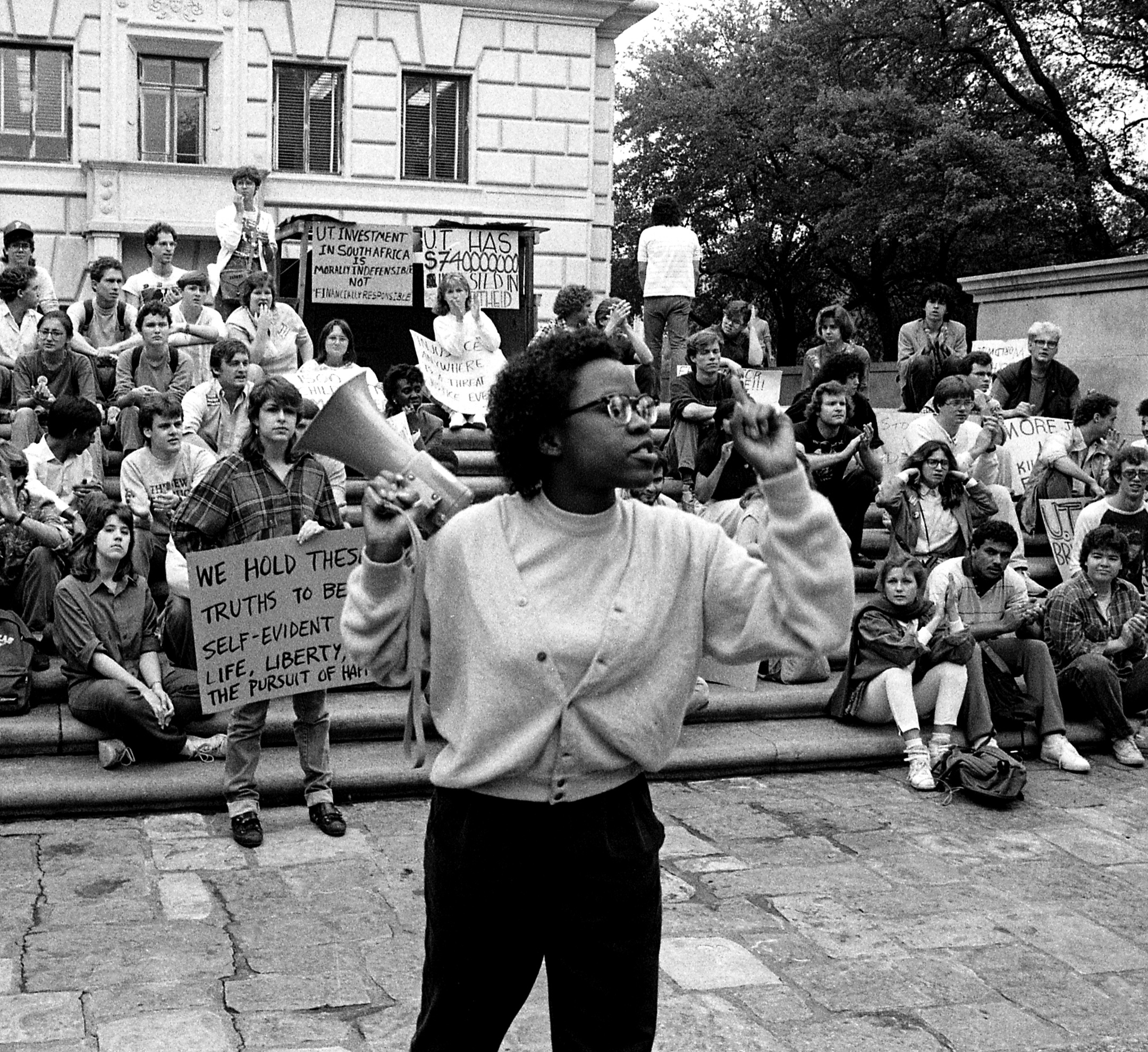

The 78-year-old documentary photographer and longtime Observer contributor didn’t have too much time to talk, as he was scheduled to shoot an open house event the radio station was hosting. So his wife, Mary Birdsong, handed me a pair of old print articles about Pogue to help me flesh out this introduction. One, a 23-year-old piece in a now-defunct Austin monthly magazine called The Good Life, detailed his journey from Vietnam battlefield medic to visual artist capturing fights for social justice worldwide. From the late ’60s on, Pogue took his camera from counterculture gatherings in Austin to farmworker marches and colonias and prisons around Texas to Iraq and the West Bank.

“Pogue takes photographs that are open-eyed and unblinking views of what many would rather not see,” wrote the article’s author, Stuart Heady, who noted as well that the Observer used to run free ads for Pogue’s photo services in exchange for paying him “just five bucks a photograph.”

A hurried search of the Observer’s digitized archive pulled up a first photo by Pogue from August 1972—an image of a Mexican-American gardener working out front of Austin’s LBJ Library, which was later used on the cover of a collection of his work titled Witness for Justice. In the following month, October 1972, an ad indeed appeared promoting Pogue’s availability to capture “political events & pseudo events” and “people in their natural surroundings.” His photos would appear in the publication for the next 50-plus years.

With press time dangling above my head like an axe, I tried calling Pogue for a closing thought about the role of the Observer in his career, but he wasn’t available. He’d gone shooting for the day, his wife said. Oh well, I had plenty of material ready at hand.

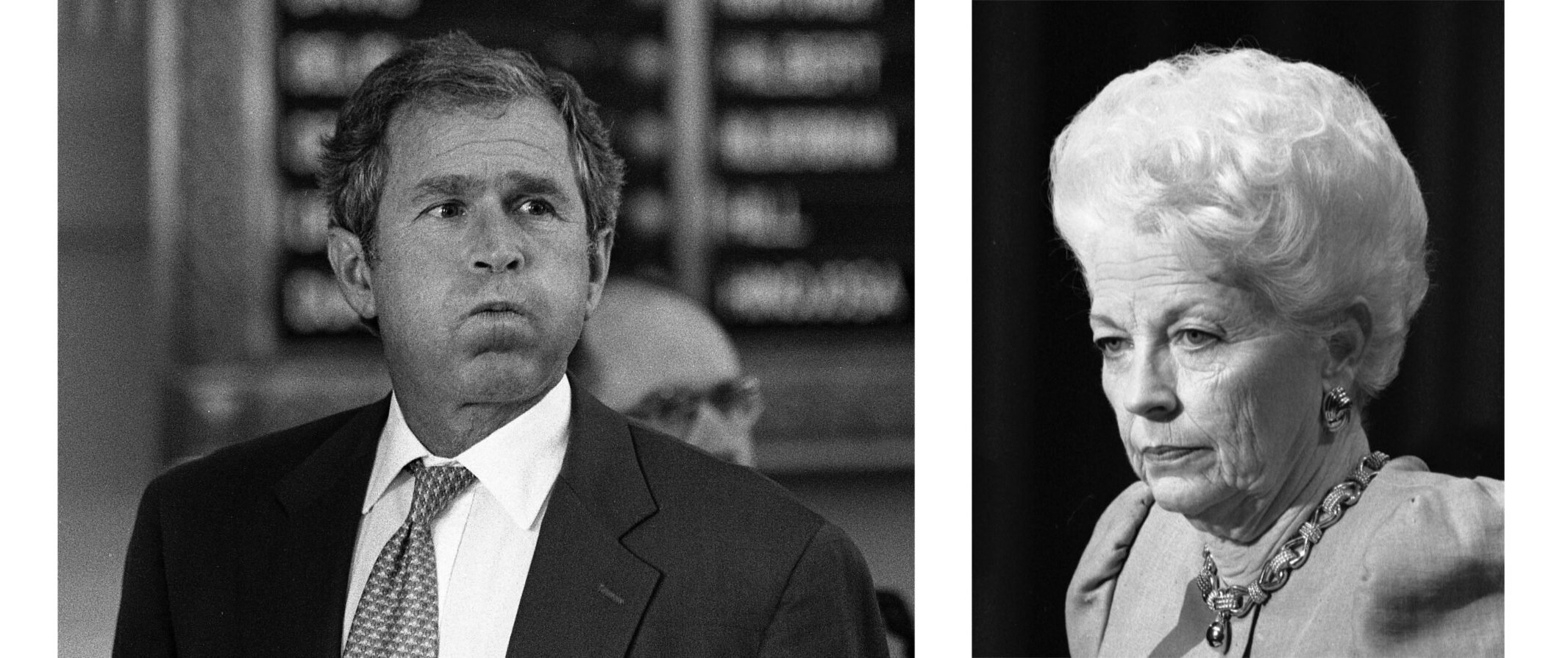

To this day, the walls of the Observer office are decorated largely with Pogue’s photos. There’s the one I love of Molly Ivins camping out in 1996 to protest Austin’s new anti-homeless ordinance, the one of longtime Observer business manager Cliff Olofson working with a cat perched on his shoulder, and the one of radio host and humorist John Henry Faulk thoughtfully reading—plus a couple that are featured in this very issue.

The history of the Texas Observer is one of world-class talents giving their labor to a broke little paper due to a shared and bone-deep belief in transforming Texas into a more just place. Arrange these talents in an auditorium, as it were, and Pogue would be sitting in the front row.

— Gus Bova