Aliens Without Borders: Exploring South Texas’ Intergalactic Attractions

A version of this story ran in the June 2014 issue.

It is cold, dark and silent in downtown Del Rio, even on a Friday night. The former Guarantee department store sits vacant on Main Street, as it has for decades. The hair salons that now occupy the old service stations are all closed for the day.

A few shadowy figures break the stillness, speaking in murmurs. Bundled against the January chill in knit hats and overcoats, they turn a corner and file into an old firehouse on Garfield Street. A party is just getting started, and they—some of the world’s leading UFO and alien researchers—are the guests of honor.

The 92-year-old firehouse building is now home to the Del Rio Council for the Arts, fronted by a gallery lined with abstract paintings. Flying saucers crafted from CDs hang on strings from the ceiling. Samples from the nearby Val Verde Winery help fuel the party, and volunteers circle the room carrying trays of “alien eyes”—deviled eggs with sliced olives set in bright-green yolks. A young guitarist on a stool in the corner sings Tom Petty’s “Free Fallin’” and Ryan Adams’ “When the Stars Go Blue.” The travelers set their coats aside and get to mingling.

Many of the faces are familiar to them from other UFO festivals in other cities, including Roswell, New Mexico, which hosts the nation’s biggest UFO festival each summer. But Roswell is far from alone, and since 2012 the alien circuit has expanded to cities along the Texas-Mexico border: Laredo, Presidio, Edinburg, and now, for the first time, Del Rio. To border-town tourism directors anxious for a reputation more savory than cartel crime, the alien invasion is welcome. Souvenir T-shirts skewer the political world’s obsession with immigration, legal and otherwise, with a slogan: “UFOs Have No Borders.”

The godfather of Texas’ Border UFO Series presides over a table set with empanadas and alien eyes in one of the gallery’s back rooms. Noe Torres—high school librarian by day, UFO historian by night—wears his authority casually in wire aviator glasses and a pink, short-sleeved, button-down shirt featuring the Roswell UFO Festival logo. He’s in demand tonight, greeting speakers for tomorrow’s lecture series and snapping photos, making sure everyone is having a good time. themselves. The Del Rio UFO Festival is the sixth such festival Torres has hosted in Texas, most of them in partnership with Ruben Uriarte, a California-based UFO researcher and Torres’ co-author on two books about UFO crashes near the Texas-Mexico border.

In 2007 the pair released Mexico’s Roswell, which describes a 1974 UFO crash in the Chihuahuan Desert. A few years later, the tourism director in nearby Presidio emailed Torres about building a festival around the incident. Torres had spent enough time in Roswell to make the necessary connections and deduce the winning formula: slideshows and research papers for serious ufologists, parades and costume contests for the kids. Two years after that first gathering in Texas, some of the top UFO and alien researchers of the day have returned to the border to do it again.

They include: Travis Walton, an Arizonan whose harrowing 1975 abduction was dramatized in the 1995 film Fire in the Sky; wry and professorial Stanton Friedman, who worked with military contractors on defense projects in the ’50s and now loves nothing more than skewering official denials of UFO incidents; and Carlos Guzman, enticingly billed this weekend as “the Stanton Friedman of Mexico.”

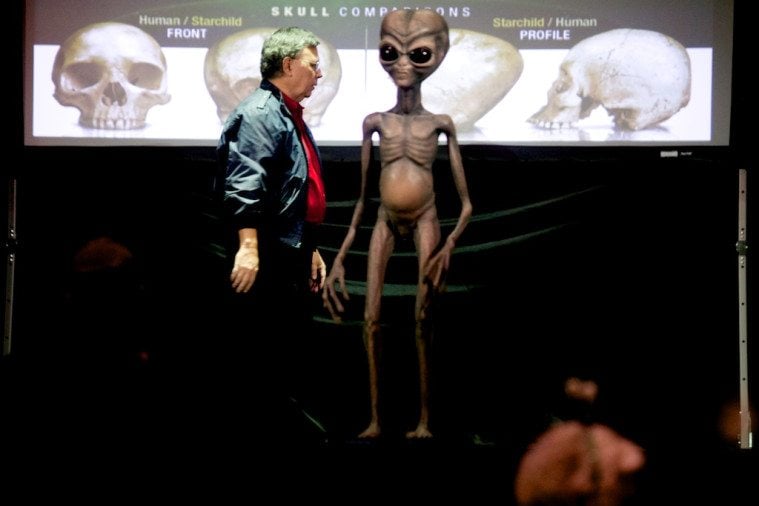

I recognize all three from their photos on the conference website. Hoping to get a read on the rest of the crowd, I introduce myself to a middle-aged couple near the front of the gallery. They’re Ray and Melanie Young, just arrived from El Paso. Ray is a retired electrical engineer, and Melanie is a nurse. She is also the keeper of an artifact known as the “Starchild skull,” an almost-human-looking but sort-of-alien-shaped skull that was liberated from a Mexican cave in the 1930s by a curious American girl who kept it for decades in a cardboard box. Young acquired the skull in the 1990s, and today she and a small team of researchers are trying to figure out whose head it used to be. As the Starchild moniker suggests, they have their theories.

For years, Young was a sort of understudy to paranormal researcher Lloyd Pye, who dedicated years to giving talks on the skull and daring academics to come up with a worldly explanation for its origin (the most common such, also unproven, is that the skull is from a hydroencephalitic child). Young tells me her mentor died just a few weeks earlier—he gave his final Starchild talk in Presidio last October—and now the job has fallen to her. The next day, Young devoted part of her talk to Pye’s memory. “He spent the last 15 years of his life trying to figure out what this is,” she told the crowd, “and it hurts me to say he didn’t make it.”

Talking to Young is a good reminder that, beyond the alien kitsch, this gathering has coalesced around a hard core of people solemnly devoted to proving that we’ve been visited from other worlds.

Not once over the course of the two-day festival do I hear the question, “Do you believe?” By the end, it feels inappropriate to ask it so tactlessly. If one does believe that aliens have visited Earth and even wrecked spaceships here, and that the government has hidden the evidence for more than 50 years, and that a handful of people know the truth and have even seen the aliens and been pulled aboard their ships, well, it’s pretty cool to be in a room with so many of those people at once—and really quite a coup for the Del Rio Chamber of Commerce.

The guitarist excuses himself and turns his mic over to Donna Langford, the town’s tourism director, who offers a ceremonial opening to the festivities, naming the locals who helped make it happen. She says she was easily convinced to bring the border UFO series here, but admits that outer space is a bit outside her wheelhouse. “I knew I wanted to have a UFO conference, but I had no idea what I was going to do,” Langford says, but she likes it so far, and expects it to be “the first of many.”

At her side, the festival’s speakers are lined up awaiting their turns to say a few words. Among them is Travis Walton, standing in front of a well-lit painting. Caught in the spotlight in his baggy brown suit, he looks as though he might beam back up at any moment.

The official mothership of the 2014 Del Rio UFO Festival is the greatest Ramada hotel I’ve ever seen. Though the swim-up bar is closed for the season, the empty swimming pool is lit with dancing neon party lights. Room-service enchiladas are just $6, and the hotel bar—the White Horse Lounge—looks to be equally popular with townies and guests from the great beyond. When I return from the downtown reception, I find a few conference-goers on the patio comparing notes with a couple of locals. The conversation moves freely from the grassy knoll to Building 7, ticking off the conspiracy bingo squares, it having been previously resolved that the government is full of shit and the truth is out there—all you have to do is Google it.

Ingrained mistrust for authority will emerge as one of the weekend’s biggest themes, as much a part of the festival as goofy alien puns—“border crossings of the third kind!”—posing for photos with alien dummies, and wondering, aloud and in earnest, about the mysteries of the universe.

A young Air Force pilot named Robert Willingham became a believer one mid-1950s spring afternoon in the sky above West Texas. Willingham, from Holliday, near Wichita Falls, was accompanying a B-47 cross-country when he spotted a strange aircraft approaching at a speed Willingham estimated at 2,000 mph. He watched as it made a 90-degree turn in midair and sped off toward Mexico. Willingham got permission to abandon his bomber and tail the UFO. Willingham watched it go down in Mexico, just across the Rio Grande from the site of Judge Roy Bean’s famous saloon in Langtry, some 60 miles from Del Rio. Later, after swapping his jet for a single-engine Aeronca Champion, Willingham and a partner returned and landed near the wreckage.

In 2008, Willingham—by then long retired and denied his government pension, he says, for breaking a military code of silence around the crash—described what he saw for Noe Torres and Ruben Uriarte, who related the tale in their second book together, The Other Roswell.

Over the years, Willingham’s story had been the subject of a local news report in Dallas and a documentary on Japanese TV. But Torres says UFO researchers had fudged the date of Willingham’s sighting to better position it within the lore of alien visits. Torres, whose writing career began with books about Texas history and baseball in the Rio Grande Valley, tries to avoid unsupported leaps from evidence to conclusion when writing about encounters with alien ships. In his book about a reported UFO sighting near Laredo, he concludes that aliens may not have been involved at all. “We don’t do a lot of editorializing and theorizing on what might or might not have happened,” he says. “We just tell the story from the witness’ perspective.”

Though cautious at first, the Mexican authorities surrounding the downed UFO let Willingham approach—out of deference, the pilot figured, to his Air Force uniform. At the end of a trail of debris, a 25-foot-diameter saucer was wedged into a sandy bluff. A few feet farther on, its domed canopy rested in the dirt. With the sunlight waning, Willingham and his partner left the craft to fly back to their airfield in Corsicana—but not empty-handed. Before climbing back into his plane, Willingham picked up a curved half-inch-thick chunk of silver-colored metal about the size of his hand. He later subjected it to heat tests and found it un-meltable. As an amateur metallurgist, Willingham was captivated by the question of what the scrap was made of. He finally turned it over to an Air Force lab for more tests. He never got an answer, and he never saw the scrap again. The scientist he’d contacted seemed to disappear. The only evidence he had left of the strange crash came in the mail two years later in the form of an anonymous note that read, “I don’t know what kind of metal it is, but I’ve never tested anything like it before.”

Willingham, 88, now lives in a nursing home in Oklahoma. His memory was already getting spotty when he gave his interviews for the book—he was no longer sure, for instance, of the year of the crash—and his health has declined since then. But it’s thanks to Willingham’s story that there’s a festival in Del Rio at all. Townsfolk, by and large, had no idea about the crash. And that’s what makes the Texas festivals different from, say, the Roswell UFO Festival, or any number of researcher gatherings. Torres and Uriarte hold their festivals near purported alien sites to tantalize alien hunters, but the events also illuminate little-known bits of hometown history for locals. Sometimes new witnesses are even convinced to come forward.

“Folks will come up and start saying, ‘You know what, I’ve never shared this experience with anyone, but I want to share it with you,’” Uriarte says. “They come to a venue like this where it’s open, and they hear other people talking, they feel safer. They’re not going to be ridiculed.”

That’s what happened in Presidio, after a festival commemorating the 1974 midair collision between a flying saucer and a small plane. Torres and Uriarte presented the evidence they’d put into their book Mexico’s Roswell, and at the end of the day local schoolteacher Johnnie Chambers and her son John walked up from the audience to say they remembered seeing explosions that day over the mountains in Mexico.

In Presidio, as in Del Rio, most locals didn’t know their hometown was a landmark of such potentially interplanetary significance. Brad Newton had only heard rumors of the UFO crash when he took over as the town’s tourism director in 2009, but he quickly saw an opportunity to draw out-of-towners to explore Big Bend’s mysterious side. Anyway, he figured, Presidio needed to fill the void left in its fall calendar where the annual Onion Festival used to be. (Presidio once claimed the title of “Onion Capital of the World,” but the onion business, and the festival, withered after labor laws enacted in the ’90s sucked the profit from the crop, which till then had been picked by low-wage workers who crossed the border for the work.)

A UFO festival offered a chance to celebrate a less fraught cross-border relationship. Newton worked with the mayor of nearby Ojinaga to host the festival’s first night on the Mexican side of the border before moving to the U.S. side for the second day. The arrangement saved some speakers the trouble of getting papers for a cross-border visit, and it was a charming gesture of the towns’ shared history; Newton says the challenge facing border-area tourism directors is to embrace their proximity to Mexico, not deny it. “The ‘Laredo is Safe’ campaign was well intentioned, but the people in Laredo didn’t realize they weren’t [considered] safe,” Newton says. “Our sister city here, Ojinaga, is definitely safe. The bogeyman doesn’t live here.”

But a 5-foot alien does. Decked out in Mardi Gras beads and a Presidio Art Fest T-shirt—but no pants—he travels around town posing for photos promoting Presidio’s next big UFO party. Most of the time he stays in Newton’s office. “In his nakedness, he’s a little bit intimidating to have everywhere,” Newton says. When Newton was planning Presidio’s first UFO festival, he scored a deal on the mannequin, which takes the glassy-eyed, scrawny-but-potbellied form of what extraterrestrial aficionados call “the grays.” Newton named it E.B.E., for “Extraterrestrial Biological Entity,” and decided it was male, though that choice seems physiologically arbitrary. To save on shipping, E.B.E. arrived in Presidio riding a Greyhound bus.

Newton, a fifth-generation Texan raised in Fort Stockton, has fun hamming it up every October, now that the UFO fest has become a Presidio tradition. He appears in character every year as a Man in Black, posing for photos with a stern face in a dark suit and black fedora. With Presidio’s festival so close to Halloween, a costume contest is a natural fit. After the lectures are done, the visiting researchers pile into convertibles and flatbed trailers for a parade through town. They investigate the Marfa Lights, check out the prehistoric cave paintings around Cibolo Creek Ranch, and hunt for ghosts at Fort Leaton, the 1848 outpost built atop a former Spanish mission where, according to one story, Ben Leaton exacted revenge on a group of Native Americans by inviting them to dinner, then unloading his cannons into a roomful of his own guests. There, the party joins with the annual Dude of the Dead Music Festival, where musicians from all around Big Bend—usually including Presidio Mayor John Ferguson and his mariachi band—converge on Fort Leaton for late-night jam sessions. “I really don’t know what the Burning Man thing is, but it’s been compared to that,” Newton says.

In Big Bend, such gatherings are in keeping with a long tradition. “We have the dark skies here,” Newton says. “You can see the Milky Way from horizon to horizon. The moon comes up, you get a moon tan.” Faced with such a display of the universe’s scale, it’s only natural to look up and wonder. The festival is a chance to wonder together.

“These aren’t crackpots. They’re credible people that have seen something that they can’t explain, and it’s a really good opportunity for folks to share their story without ridicule,” Newton says.

It’s the same story at the Del Rio UFO Festival, which features a Friday night ghost hunt in downtown’s 67-year-old Paul Poag Theatre. Saturday’s lectures include one by Torres and Uriarte, who relate Willingham’s tale of the UFO that crashed about seven years after the theater was built, and just a few miles away.

Vendors sell snacks and hot coffee in the lobby—the heat is out and the theater is freezing—and a few of the speakers sell their books at a line of tables. Even the most otherwise serious-looking member of this crowd of 400 or so is wearing a headband with green alien heads bouncing on springs. Onstage, Del Rio’s own alien mannequin—this one is named Phish—presides silently over the affair. There are plenty of retirement-age couples in the crowd, and almost as many people of high school or college age. Whole families have turned up with little kids, too, to spend the day at an event that—despite the offbeat subject matter—is basically a lecture series.

Tonight there’ll be a parade, then a costume contest and a party in the park.

To Uriarte, the alien-head headbands and costumes are the cost of doing business, but a little embarrassing nonetheless. “It’s almost like you have to develop a carnival-type atmosphere to attract people, and that’s just part of it. You almost have to look the other way, seeing the guy with a tinfoil hat,” he says. “But on the other hand, they’re there to learn.”

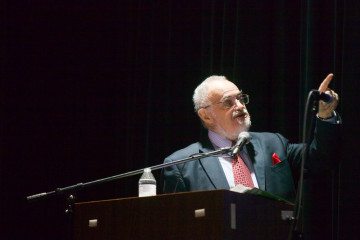

Saturday’s programming is dense. Each of the presentations, stacked one after the next with a short break for lunch, deals obsessively with dates, times and other forensic minutiae. Even Travis Walton—relating the story of how he was knocked unconscious, sucked aboard an alien ship, awakened on an operating table, and how he scrambled for freedom through the ship’s corridors—spends half an hour picking apart police records and the faults in Hollywood’s treatment of his ordeal before delving into the crowd-pleasing territory of UFO layout sketches and existential dread. Stanton Friedman gives two lectures—one a sort of primer on UFO evidence, the other romantically titled “A New View of the Cosmos”—both full of facts and photographs of primary documents. Faced with broad skepticism, ufologists like Friedman rely on precision and exactitude in defense.

In their quest to make sense of the universe, today’s mainstream scientists peel away history fractions of a second at a time, back toward the inscrutable moment when everything began. Before the earliest moment we can grasp, there’s only speculation and faith. For most of us, the existence of life on other planets—big, sentient animals with spaceships who can come find us—is another such mystery. We reach for an answer, collecting clues along the way, but never quite know. The question we ask each other, in the absence of proof, is whether we believe.

Friedman and many others in this Del Rio theater already have their answer. The more maddening question is why others disbelieve so fiercely. Friedman has been fighting skeptics for decades, and he must have long ago tired of repeating the same old debates, but it’s still startling to hear the ferocity with which he lays into someone like popular astrophysicist Neil deGrasse Tyson for doubting the UFO record. But after putting his reputation on the line for so long, it’s no wonder Friedman takes it personally. “If they can’t attack the data, [they] attack the people,” he explains. “They think we’re idiots. I don’t think we are.”

Melanie Young, keeper of the Starchild skull, seems similarly bedeviled by skeptics. “This is serious science,” she reassures us during her talk. “It is not a hoax.” She complains about how much time she spends online, trying to set the skull record straight. She reserves particular scorn for what she calls “Wackipedia.”

“There is a conspiracy, if you will, against the Starchild skull,” she says.

I’d naively hoped to get a look at the skull this weekend, but as Young proceeds through her PowerPoint it becomes clear that won’t be happening. Eventually, she casually mentions that of course none of us will see the Starchild skull at an event like this—a roomful of human DNA could contaminate it.

“Are you worried about the government seizing it?” someone asks at the end of her talk.

Young pauses before answering: “None of us are willing to die for it.”

Her words hang over what feels to me like an uncomfortable silence before the applause takes hold and she leaves the stage.

In June, Edinburg’s new convention center will play host to the next UFO conference, with headlining experts on the Roswell crash and alien abductions. Del Rio will repeat its UFO festival next year as well. Uriarte says they like to vary the subjects—government conspiracies, alien sightings, cattle mutilations—and find new speakers to keep the programming fresh.

On Saturday night in Del Rio, the packed theater empties onto Main Street and the crowd parades to a downtown park. The festival’s VIPs ride a flatbed trailer complete with a lit-up silver UFO. Beside a pagoda, Langford announces the winner of the costume contest: a local family doctor who, like his wife, is wearing bright-green face paint, an olive-green jumpsuit and a pair of antennae. Their little black dog is wearing an alien costume too. For besting the other contenders, the doctor wins tickets to Roswell’s UFO museum, a Fire in the Sky DVD, and a free trip to the Gatti’s Pizza buffet.

Walton and Friedman hold court at a folding table nearby, posing for photos and signing books. Friedman tells me later that this is his favorite time of any festival: chewing over mysteries with the locals. Though he remains as pedantic offstage as on, he’s charming one-on-one and seems younger in this context than his 78 years. As Friedman fields metaphysical theories from strangers, Walton answers questions about his abduction. The small crowd leans in to hear more, locals and out-of-towners, devout believers and agnostics alike, sharing the glow of the trees strung with lights, wondering together at the darkness all around.