All Walled Up

How Brownsville's battle against the federal government's border fence ended in defeat and disillusionment.

In the early spring of 2008, the uniformed Border Patrol officers delivering condemnation notices door-to-door seemed surprised by the defiance they met from Brownsville landowners. The first time the officers came, it was with clipboards and a few documents to sign—the feds like to call it a “friendly condemnation,” which means folks are expected to happily sign away portions of their land for meager compensation from the U.S. government.

Along the border, it’s not unusual for landowners to take a look at the legalese, stare at the olive drab uniforms and shiny gold badges, and sign on the spot. But in Brownsville and Cameron County, many glanced at the words “taking” and “U.S. government” and showed the agents the door.

The next time the Department of Homeland Security came calling, all pretense of “friendliness” was gone. With real estate specialists from the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers in tow, they now had pointed words. Congress had mandated the building of a 670-mile fence along the southern border in its 2006 Secure Border Fence Act. Sign the form or not, residents were told: The government will get its land.

The sterner message had little effect. Those who had the money, or the pro bono attorneys willing to help, filed lawsuits against DHS and dug in their heels. The battle of Brownsville—the most pitched and prolonged fight along the Texas border—was joined.

It wasn’t just landowning citizens who were up in arms. Brownsville Mayor Pat Ahumada, insisting the wall would split his already-troubled community and wreck its hopes for the future, became one of the nation’s most outspoken opponents of the “security fence.” Juliet Garcia, president of the University of Texas at Brownsville, declared that the government was not going to build its wall through the middle of her campus.

Garcia channeled popular sentiment in Brownsville with her statement on the federal agency’s move to seize property: “Of course, we believe in protecting our borders. Of course, we believe in strong immigration policy. But we also understand that a fence, no matter how high or how wide, is no substitute for either.”

Residents marched in protest. Ahumada joined other border mayors and lobbied Washington. University students picketed the federal courthouse. Brownsville caused such a commotion that Congressman Raul Grijalva, an Arizona Democrat, scheduled a public hearing at the university that April. Dozens of students and residents gathered outside, holding signs reading “Build Bridges Not Walls” and “No Wall Between Amigos.”

Inside, border-fence champion Tom Tancredo, then a Republican congressman from Colorado, was flummoxed by the fierce opposition. As one resident after another stood up to protest the plan, Tancredo huffed: “Why don’t we just build the fence north of Brownsville then?” Responding to a letter from Ahumada after the hearing, Tancredo shot back: “This is a matter of national importance, and the American public should not be asked to sit back and allow a handful of local governments and their friends in the ‘open borders’ lobby to exercise veto power over something that impacts not only our security, but our national sovereignty.”

Brownsville staged a lively rebellion. For a while, an unlikely victory seemed possible, thanks in large part to Andrew Hanen, the only federal judge in the nation who forced Homeland Security to acknowledge landowners’ constitutional protections. In case after case, Hanen refused to rubber-stamp the condemnations and ruled that the government would have to provide “fair compensation” for the land it was taking.

Residents pinned their hopes on dragging out their lawsuits long enough for President Barack Obama to take office. They expected him to send his Homeland Security team to take stock of the environmental and economic damage being done by the steel-and-cement monstrosity, and halt construction on a project whose $2.4 billion cost continues to rise. Those hopes were dashed when Obama announced the “secure fence” would be finished. In a final plea last May, Brownsville residents (along with others along the border) wrote a letter to the new president. “Absent your intercession, a great, lasting and damaging injustice will be dealt to the people of the Texas-Mexico border,” it read in part.

Obama never answered. More than 27 miles of border wall now snake raggedly through Cameron County. Only seven more miles remain to be built.

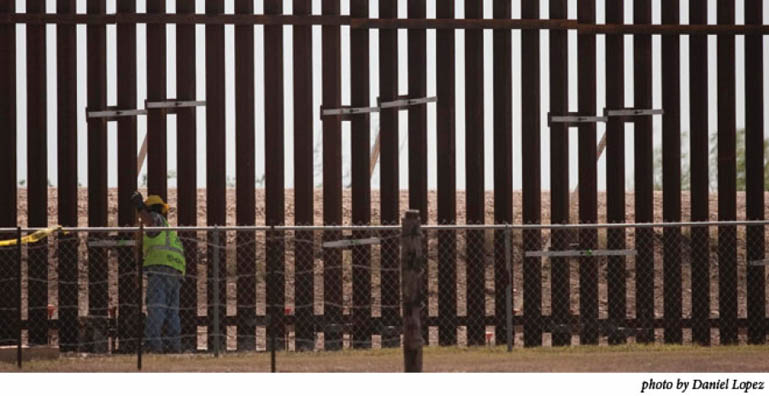

The rust-colored, steel-and-cement wall has become a surreal fixture on Brownsville’s skyline. It cleaves downtown Hope Park, built as a symbol of unity between the United States and Mexico. It stops and starts, without rhyme or reason, along the Rio Grande River’s levees, leaving miles of gaps. It highlights the city’s economic divide: It’s the first thing folks in the poorer barrios see when they look out their windows, while richer folks enjoy unaltered views of palm trees and manicured fairways when they tee off on private golf courses. It zigs and zags through residents’ backyards, through citrus orchards—an ugly red scar on a green, subtropical landscape.

“We don’t call it a fence,” says Ahumada. “It’s a wall. A fence is something you’d want to put up in your backyard.”

On an unseasonably frigid Friday morning in early January, the mayor sits in his downtown office sipping coffee and recounting the arguments he tried to make to Washington. “This wall has killed Brownsville,” he says. “We have a per-capita income of $14,000 per household, high unemployment, a high dropout rate. We don’t need a wall to compound the problems we’re already having. What we need is an investment from the federal government to help us fulfill our future.”

As he speaks, Kiewit Corp., one of the nation’s largest construction companies, is busy draining resacas (lakes created by the shifting tides of the Rio Grande) and bulldozing citrus orchards to build those last seven miles of wall through Cameron County. To date, 199 county residents have had land seized, according to U.S. Customs and Border Protection figures. Every day, the Brownsville Herald publishes government notices of the properties to be condemned by the Department of Homeland Security.

The agency is already one year late and several million dollars over budget in fulfilling Congress’ 2006 mandate—and counting. The Secure Fence Act was cobbled together so poorly that legislators failed to take several important factors into consideration. For one, thousands of private landowners would have to forfeit their land—and not all would go willingly. For another, a 1944 treaty forbade construction of anything in the Rio Grande floodplain that would push floodwaters into either Mexico or the United States.

Because of the treaty, DHS was forced to build its wall north of the river’s levee—sometimes as far as two miles upland. In Brownsville, the 8-foot-tall earthen levee follows the twists and turns of the Rio Grande for several miles. The mayor had seen the river shared with Mexico not as a security threat, but as a selling point for his city. Before the wall, Brownsville had plans to build a river walk like San Antonio’s—an anchor for downtown revitalization and a transit loop that would spur more commerce.

“We had a private investor group from California looking to invest $150 million in the downtown revitalization with the river walk as the anchor,” Ahumada says, “but they backed out because of the wall.” Making matters worse, DHS ran the wall close to the planned transit loop. “To build the loop now, we would have to move the border wall and put it somewhere else to the DHS’s specifications,” he says. “We estimate it would cost the city $13 million a mile.”

In June 2009, Brownsville council members finally voted to surrender 15 acres of city land to the federal government despite many residents’ persistent opposition. Ahumada never resigned himself to it. The two-year-long debate over ceding land to the DHS bitterly divided the city government—especially after the council’s majority agreed to perhaps the worst deal struck by any border community. They forfeited the $123,100 DHS had offered to buy the land and allowed, without compensation, a “floating fence” with 15-foot steel posts stuck into a concrete base to be built downtown.

What does Brownsville get in return? According to its contract with DHS, the city agreed to eventually build a combination levee-border wall, a permanent structure to replace the floating fence. Brownsville taxpayers will foot the entire bill, last estimated at $12 million to $16 million per mile.

So the battle of Brownsville became a surrender. But a few folks still fight on.

Seventy-two-year-old Leonard Loop lives on the outskirts of Brownsville, where he flies the American flag outside his feedstore. He’s as patriotic as anybody: an Air Force veteran whose wife used to work for the State Department. Two years ago, when he got wind of the government’s plan to seize their land, he called a family meeting.

“We sat down and talked about it and decided we had to do what was right,” Loop says. “My sons own the 730 acres on the river side of the fence. It’s their livelihood, and they are in deep debt for it. I told my boys, ‘the federal government will ruin you if you don’t stick up for your rights.'”

The Loop family filed suit against DHS. Leonard Loop likes to call it his “disagreement.” It’s gone on for 18 months now.

Like most folks around Brownsville, Loop says he’s all for border security. But the wall hasn’t made anybody safer, he says. In fact, just the opposite, especially for those—like his sons—who will be locked out on the river side of the wall with access controlled by the Border Patrol. Besides, Loop says, a poorly constructed fence with miles of gaps doesn’t exactly spell security. “I heard they already figured out a way in Mexico to use old motorcycle tires to climb the fence. They jam them in the gaps and climb it like a ladder.”

Loop owns 160 acres dotted with citrus orchards. He and Debbie, his wife, sell sweet Rio Red grapefruits and oranges at their feedstore. Their sons, Frank and Ray, grow cabbage, corn, and other vegetables on their 730 fertile acres along the riverbank. The Loops have farmed here for almost four decades. Even now, their lives are mostly marked by tranquility and backbreaking work. Occasionally, their routines are punctuated by bizarre moments that remind them they live along an international border. “I once saw a truck being chased by the Border Patrol drive into a wheat field,” he recalls. “The driver fled on foot and left five women behind in their underwear who had just swum across the river.”

The Loops occupy a particularly breathtaking patch of the Rio Grande. There’s a horseshoe-shaped resaca full of bass and catfish, lined with palm trees. There’s a pavilion on the river’s edge they use for family reunions and church picnics. They don’t make a mint off this land by a long shot. But it’s easy to see why they won’t give it up without a struggle.

On a bitter-cold January afternoon, Loop tells me he’s been up since 2:30 a.m. trying to save his citrus orchards from Brownsville’s first hard freeze in 20 years. No matter how exhausted he is, the notion of what the government’s done still raises his blood pressure. “This has been a learning experience,” he says. “I never thought this country would treat you that way.”

Last November, DHS sent bulldozers to mow down Loop’s grapefruit orchard. Then they drained a resaca and condemned his nephew’s driveway to start building the wall through the family land.

When it’s finished, Loop’s nephew and his son Ray’s family will live on the Rio Grande side of the wall—part of more than 50,000 acres of U.S. land along the river that will be walled off by the fence from the start of the levee in Hidalgo County through Cameron County. Leonard, Debbie and their other son will live on the other side. Homeland Security is building a 50-foot gate. The agency, Loop says, refuses to tell him whether his family members and their employees will be able to use it without a Border Patrol escort.

Loop says a federal official told his son Ray that if there were an orange alert—meaning a high threat level—his family would have to evacuate their home and the gates would be locked behind them. That strikes Leonard as especially ludicrous, since the segment of wall that cuts through the land will end a half-mile away from his property—commencing a 14-mile stretch of levee, largely federal land, that won’t have any fence at all. “You can just walk around it and do anything,” he says.

Claude Knighten, a public information officer for U.S. Customs and Border Protection, tells the Observer he’s not aware of the orange-alert policy. His e-mailed response was that the agency “has no knowledge of this statement and therefore cannot respond.”

That’s the kind of thing that galls Loop the most. He can’t get reliable information from the government, he says, so his family can plan for the future. “Initially, when we got into this 18 months ago, I thought the government would work with us, and we would sit down and discuss things like access,” he says. “But they just do whatever they please whether it’s right or not.”

At first, the government seized a 60-foot-wide strip of Loop land starting at the base of the levee. Then they took a 120-foot-wide strip. “First they told us we could drive on the levee. Then they told us we couldn’t,” Loop says. “How can a landowner feel safe when the government keeps changing its mind all the time?”

Loop falls quiet for a moment as we roll up on the levee in his silver pickup truck to where the Kiewit Corp. workers are building the fence that cuts through his orchard. Majestic pink spoonbills and white egrets forage for food in a half-drained resaca. A worker on an earthmover is filling the lake with mud.

“They can do that,” Loop finally says. “Homeland Security waived all the environmental laws. It’s unbelievable the power they’ve got.”

Two Border Patrol SUVs are parked side-by-side, blocking the levee up ahead. As we’ve circled his land, we’ve been under constant observation by the Border Patrol. Recently, Loop was told he could no longer drive the levee, which he must cross to access his son’s property and reach a portion of his own. “They haven’t paid me yet for the second condemnation,” he says. “As far as I am concerned I can still drive the levee till they pay me.”

Loop contemplates the situation, then turns back onto the highway. “There are so many things that don’t make sense,” he says. “I’m no expert, but I was born and raised down here, and I know what things are like on the border. The guys who are calling the shots—they’ve never lived here, and they have no idea what it’s like.”

Loop is slated to receive $24,900 for the three acres the government has taken. His property valuation has plummeted. The only thing he can hope to achieve now with his lawsuit is better compensation for his land. Nobody would buy it now, he says, with an 18-foot wall running through the middle of it. “The only buyers I could see interested in riverfront property now are the drug cartels or the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.”

“I feel like we live in an occupied zone now,” says 74-year-old Eloisa Tamez. Early on the coldest Saturday morning in memory, Tamez, a nursing professor at UT-Brownsvile who looks 20 years younger than her age, sits in her modest home on her family property. An heir to a 12,600-acre Spanish land grant deeded by the king of Spain to her family in the 18th century, Tamez is struggling to hold on to the last three acres. Like Leonard Loop, she feels like she’s going to be the last holdout in Brownsville—battling the government not only for her family, but for all the border landowners intimidated into signing away their rights or giving up because they couldn’t afford court battles.

“People stop me all the time in the store or recognize me at the bank, and they say, ‘Good for you. Keep on fighting the government,'” Tamez says.

She’s been able to carry on thanks to lawyer Peter Schey at the Center for Human Rights and Constitutional Law in Los Angeles. He has handled her two-year-old case against DHS pro bono. “I will not give up my land,” Tamez says. She intends to leave it to her grandchildren.

The government has other ideas. Last summer, it seized one of Tamez’s three acres. While she was at a conference in Colorado, contractors erected the 18-foot wall outside her house almost overnight. They didn’t give her a gate, and now they want to bar her access to the levee—as they are doing with the Loop Family. That would cut Tamez off from her riverfront property.

Tamez believes it is punishment for having been one of Brownsville’s most vocal critics of the wall. “Homeland Security has been very aggressive,” she says. “Border Patrol agents rush over to my car and start questioning me whenever I drive on the levee. I haven’t been to my property on the south side of the fence since July.”

In December, Tamez rented out her deceased aunt’s home, which sits right next door to her own. Her tenant, a security guard who works at night, complains that the Border Patrol had stopped him to check his citizenship status on his way to work. He reports that Border Patrol agents often park outside the house. His family feels like they are being watched.

“They are intimidating people and stopping cars all the time to check citizenship,” says Tamez. “Border Patrol agents should recognize our cars and know that we live here by now.”

Traffic stops by Border Patrol to check citizenship status are routine in Brownsville these days. The green-and-white SUVs constantly race up and down the levees, leaving plumes of white dust in their wake. Steel towers with video cameras dot the South Texas skyline, and, now, the 18-foot wall.

“Where are our rights?” asks Tamez. “We are U.S. citizens, too.”

Mayor Ahumada wonders the same thing. When will Washington start listening to the people who live along the border?

“In terms of providing the security we need against illegal drugs and deterring illegal immigration, this wall has not helped us. In fact, it’s hurt us,” he says. “The congressional leaders like Tancredo who wanted to build a wall here—they did it to get votes from the interior of America so they could appear to be doing something to protect our country. We’re just a pawn in the political chess game.”

Increasingly, racism is cloaked in border security, he says. “Interior America is clamoring for anti-Mexican rhetoric. They disguise it under border security, but it’s racism in my opinion. We have an immigration problem, but what are they so afraid of?”

Clearly, they were not afraid of the citizens of Brownsville.