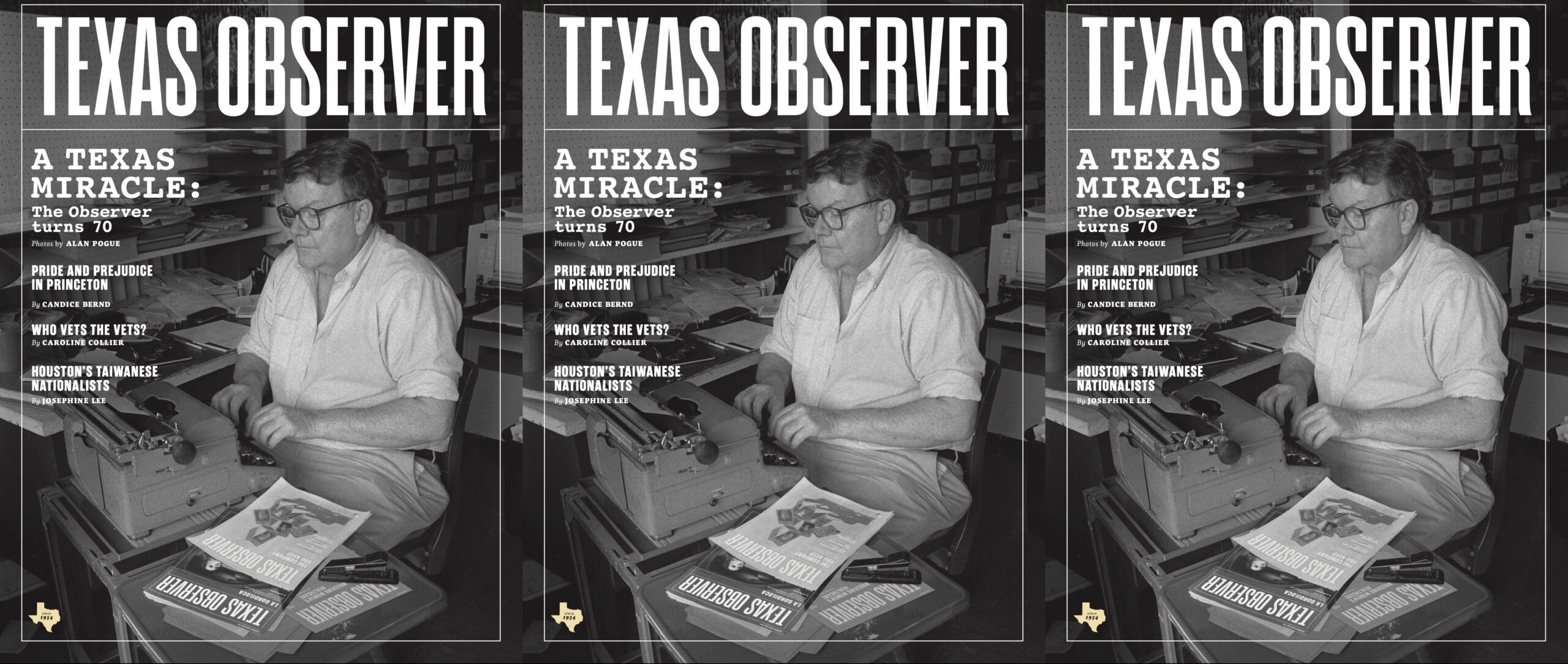

‘American Born Chinese’ and the Limits of Cultural Representation

The young hero in the new Disney+ show follows a familiar journey for colonized people, as predicted by theorist Frantz Fanon.

Before the May premiere of his American Born Chinese TV series on Disney+, and following Oscar wins for the movie and actors in Everything Everywhere All At Once, the TV show’s executive producer Kelvin Yu celebrated the strides Asian Americans have made in the film industry at the South by Southwest Festival.

I watched as the mostly Asian audience in Austin applauded Yu, claiming this victory, and more to come, as their own. As an American-born Chinese myself, who grew up watching media depictions of Chinese females as conniving concubines, overbearing tiger-moms (I actually have one of these), or docile students, who let their white peers copy their homework (never in my life!), it was easy to soak up the positive cultural affirmation generated by the recent wave of Asian-American representation in films.

It’s harder, on the other hand, to see how all this progress translates to my everyday reality and those of others in Chinese-American working-class communities.

“We made it!” the South by Southwest crowd cheered. But wait, I thought. Where is “it?” And who are “we?” It turns out those are the very questions that American Born Chinese, the show we saw together that day, struggles to answer.

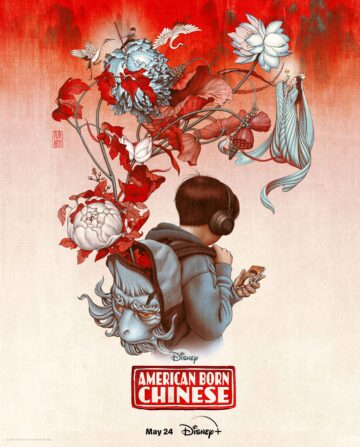

American Born Chinese, based on Gene Luen Yang’s graphic novel of the same title, is a coming-of-age comedy that masterfully interlaces the stories of Jin Wang (Ben Wang), a Chinese-American teenager, and characters from the Chinese Monkey King folklore against the backdrop of a fictional racist TV show called Beyond Repair. Jin goes through an identity crisis. He’s caught between the racist tropes perpetuated by Beyond Repair’s character Chin Kee and the weight of his heritage represented by Wei-Chen (Jim Liu), the defiant mythical son of the Monkey King, who pushes Jin to be a more “confident dude” and proud of his identity.

The trouble is that Jin, the series’ main character, has no idea who he is.

At school, Jin recoils when he spots a trending meme of the TV character Chin Kee, a thick-glasses-wearing, heavy-accent-dripping, bumbling, bootlicking foil to the all-knowing white male protagonist in Beyond Repair. In order to repudiate this image, Jin longs to be white. He steals a jean jacket, joins the soccer team, and pretends to jet ski to fit in with the white boys. He turns his back on Asian friends and thumbs his nose at all things Chinese, which almost made me shout at the screen: “Try the chicken feet, Jin! You’ll like them!”

He turns his back on Asian friends and thumbs his nose at all things Chinese, which almost made me shout at the screen: “Try the chicken feet, Jin! You’ll like them!”

Many of us who endured our adolescence feeling like outsiders in America experienced a similar identity crisis. Postcolonial theorist Homi Bhabha describes this as a “splitting of the ego,” caused by the binary representations we see in the media: The white middle class is everything that is whole and good, compared to Others, who are who “savage and yet the most obedient and dignified of servants … rampant sexuality and yet innocent as a child … mystical, primitive, simple-minded and yet … a manipulator of social forces,” Bhabha writes. As a result, the racial and ethnic stereotypes we see in the media tend to separate and alienate us.

In a Time magazine article, Charles Yu, the Chinese-American writer of American Born Chinese and brother of executive producer Kelvin Yu, has also written about cultural misrepresentations in TV and film: “Like it or not, they’re the stories we consume. … What we consume and then produce and then consume, where we go to see what we believe about ourselves, and believe what we see.”

Inside this perverted “feedback loop,” as Kelvin Yu calls it, the more Jin tries to disavow his Chinese-ness, the more he reinforces and reproduces racist stereotypes. In the series, Jin essentially becomes Chin Kee after he is videotaped accidentally mimicking a clumsy collision from Beyond Repair that is then shared by Jin’s false “friends” in a racist meme.

This example of the show’s fiction becoming the main character’s reality made me think of another question Charles Yu has asked in his writing: “Is there a way to stop this feedback loop?”

Postcolonial theorist Frantz Fanon’s article “On National Culture” offers an answer to Yu’s question. Fanon outlines three phases in the cultural development of formerly colonized people. (I use the term “colonized” more loosely to mean people who have been racially or ethnically marginalized, who possessed or perhaps still possess a “colonial mentality,” assuming their oppressor’s culture is superior.)

Taught to believe our culture is inferior, we initially try our best to assimilate, to adopt the dress, mannerisms, and worldview of the white middle class until we “identify with them completely,” Fanon writes.

While I didn’t pretend to jet ski like Jin did in American Born Chinese, I spent many mornings before school arguing with my mom to give me an American sandwich for lunch. What I usually found in my lunch bag later was one wilted leaf of lettuce between two slices of bread.

Jin’s inner turmoil and the trajectory of the American Born Chinese TV series also cover a second phase of intellectual development that Fanon describes. At some point, the colonized awakes and exclaims, “WTF have I become? Who am I really?” And at that point, devoid of connections to or positive representations of their culture, the colonized “casts his mind back,” to histories and myths. “In order to escape the supremacy of white culture, the colonized intellectual feels the need to return to his unknown roots,” Fanon writes. “Old childhood memories will surface, old legends will be reinterpreted on the basis of a borrowed aesthetic, and a concept of the world discovered under other skies.”

Thus it is the mythical character Wei-Chen, the son of the folkloric Monkey King who descends from the Heavenly Realm to impact Jin’s world in American Born Chinese. In the original Chinese legend, the kung-fu fighting, self-cloning, 72-types-of-transforming simian turns the heavens upside down before he brings the scrolls of Buddhism from India to China.

In American Born Chinese, the Monkey King has morphed into an agent of law and order as he attempts to bring a rebellion in the Heavenly Realm and his son to heel.

Liberation for both Jin and Wei-Chen seems to rest on their developing alliance. While Jin is soft spoken and submissive, Wei-Chen is loud and defiant. Wei-Chen has almost mastered his father’s ass-kicking kung-fu skills and is determined to use them to prove his worth and to defend Jin against racist classmates. Wei-Chen is that badass figure of which all Chinese-Americans can be proud.

But, Fanon cautions against our Asian cultural representations becoming stuck in legends, traditions, and essentially “frozen in time.”

Even in literature, authors tend to glorify ancient feudal hierarchies, relishing the ploys of the oppressive elite.

I saw examples of this in my own high school days, when my friends and I staged ethnic fashion shows wearing those scratchy, tight-fitting qipaos that no one in China wears anymore. In Chinatowns all over America, statues of Confucius, the authoritarian misogynist patriarch, are mounted. In some of the best films, TV and books stereotypes get repeated: immigrant mothers retrace their memories in Joy Luck Club, a fiance returns to an over-the-top opulent homeland in Crazy Rich Asians, and mythical dragons are slayed or saved in Disney’s various Asian-represented films. Even in literature, authors tend to glorify ancient feudal hierarchies, relishing the ploys of the oppressive elite.

Fanon warns that clinging to what he calls the “mummified fragments” of past myths and histories can obfuscate our present reality.

All this reminds me of an incident that happened to me last year while I stood with other workers on the picket line in front of the Museum of Chinese in Americas in Manhattan’s Chinatown. The working class Chinese immigrants there had initiated the protest after the museum’s wealthy Chinese-American board members pushed for gentrification. The group greenlit the City’s wildly unpopular plan to build a jail, and shuttered the neighborhood’s largest restaurant, actions that displaced both residents and workers. In exchange, the museum received millions from the city to fund programs to address anti-Asian violence.

I was there when an Asian-American group of tourists arrived to visit the museum. One turned on us, cursing and shouting, “I need this museum! Why are you trying to take it away from us?!”

Again, I thought, who is the “us” this woman is speaking of? Certainly not those she spat upon. To this woman, the “mummified fragments” of a curated culture were more real than the people standing in front of her.

For Fanon, authentic culture should be a wave that incessantly rolls and ripples to reflect the struggles of the people, the community and not just the individual. But I believe how we define our community becomes problematic if we simply define it in terms of our race or ethnicity. While shows like Crazy Rich Asians and Bling Empire might lead people to believe that Chinese-Americans are generally rich entrepreneurs, the majority of Chinese in America are working class. As a working parent, I have little in common with the Chinese bankers and landlords on the board of the Museum of Chinese in the Americas or Houston’s Chinese Chamber of Commerce, the wealthy elite who often use a type of cultural paternalism to exploit their own people.

We end up fighting for the recognition of the individual within an unjust system instead of fighting collectively to end systemic oppression.

American Born Chinese’s own ambiguity about who is “the community” appears in a scene when another character, a Japanese student named Suzy Nakamura (Rosalie Chiang) protests the racist meme of Jin, saying “I don’t speak for my face, I speak for my race.” Poking fun at generalized pan-Asian representations in the media, the show’s creators seem to settle on the popular slogan, “We’re not a monolith.” While true, this concession tends to glorify the individualistic desires of Asian-Americans and obscure very real issues of exploitation and oppression. If we settle on this reductive analysis, then we end up fighting for the recognition of the individual within an unjust system instead of fighting collectively to end systemic oppression.

The colonized intellectual who chases after individualistic petty bourgeois aspirations—to have a seat at the table, to earn a promotion among the boardroom executives (like Jin’s father in American Born Chinese), or even to stand on the Oscar stage—is still detached from the majority of their people.

It is the third phase of cultural development Fanon describes that offers a path for the future.

In that phase, the colonized intellectual finally leaves behind their infantile and superficial notions of the past and engages in present struggles, producing art, books, and films that reflect the fighting spirit of the masses. Perhaps these are works that Disney would never produce, but that could, as Fanon writes, “open up the future, spurring people into action and fostering hope.”

Perhaps, if we, as Chinese-Americans, or other Asian-Americans, realize that the destiny of our people is inextricably linked to the destinies of other communities; if we engage in the struggle facing the majority working class in America; if we refuse to be promoted or pitted against other groups; then we could liberate ourselves from the feedback loop of cultural alienation and fetishistic representations. Someday, I hope to see a film about that.

This is part of our coverage of South by South West (SXSW) 2023.