‘American Wolf’ Explores How People and Predators Should Coexist

Blakeslee takes readers deep into a genuinely human tale told with the energy and verve of a best-selling thriller.

Since Europeans first ventured across the American West — equipped with rearms and a sense of godly duty to transform what they perceived as a savage wilderness — the region has been divided by tensions between conservation and development. From the near extinction of the American bison in the late 1800s to the Sagebrush Rebellion over land management in the 1970s and ’80s, the West has always been a place where people and nature come into conflict. Most recently, this was personified in Cliven Bundy, whose two-decade-long miniature rebellion against paying grazing fees on public lands captured headlines when it grew into an armed standoff in 2014.

Few of these fights have been as long-running or as divisive as the attempts at wolf repopulation in the Lamar Valley, a remote area within Yellowstone National Park. Since the gray wolf was reintroduced to Yellowstone in 1995, conservationists and tourists have clashed with ranchers and hunters over how, exactly, predators and people should coexist.

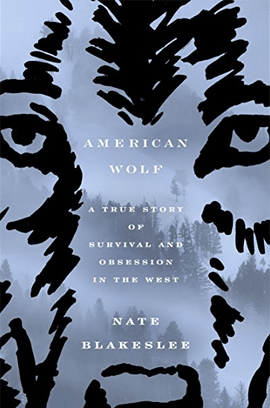

by Nate Blakeslee

CROWN PUBLISHING GROUP

$28; 320 pages

That’s the question at the core of Nate Blakeslee’s new book, American Wolf: A True Story of Survival and Obsession in the West. Blakeslee takes readers into the snowy valley, and deep into a genuinely human tale told with the energy and verve of a best-selling thriller. A tight, dense narrative, American Wolf races along like a predator on the hunt. This is no easy feat, especially because Blakeslee had to reconstruct the bulk of the story from hundreds of hours of interviews and years’ worth of meticulous notes kept by park ranger Rick McIntyre and wolf- watcher Laurie Lyman.

History and science are both key to understanding the state of the wolf in America today, and while Blakeslee deftly weaves both into his account, readers searching for pure wildlife biology or natural history will be disappointed; this is primarily narrative nonfiction. For most readers that will be a blessing, because it’s exactly what longtime Texas Monthly contributor (and Observer alum) Blakeslee excels at.

American Wolf is reminiscent of John McPhee’s science-centric, personality-driven, abundantly readable nature journalism. It’s informative and grand, moving back and forth from quiet game trails and tiny county courthouses to Washington, D.C.

A tight, dense narrative, American Wolf races along like a predator on the hunt.

The stories of dedicated hunters like Steven Turnbull and conservationists like McIntyre are thoroughly researched and told with sympathy and the knack for storytelling that has earned Blakeslee a handful of nonfiction prizes. It’s no surprise Leonardo DiCaprio’s production company has already snatched up the film rights: Vast portions of the book feel remarkably cinematic, including extended scenes of O-Six, a pack-leading female wolf that serves as the story’s central character.

Notably, the generations of wolves tracked in the book are never anthropomorphized. They truly are wild animals, though Blakeslee describes their particular traits and habits. “To O – Six, the road meant nothing,” he writes. “To her, a car was like anything that was neither predator nor prey — like a rock or tree or even a bison.”

The book also puts a 21st-century twist on age-old themes of tradition, modernity and ethics by adding a sense of celebrity and social media stardom not only to O-Six, but also to McIntyre, her dogged tracker and defender. “Like a grizzly or a bald eagle or any of the park’s traffic-jam-inspiring attractions,” Blakeslee writes, McIntyre had become an attraction himself; “he had been sighted.” Buoyed by the reintroduction of wolves to Yellowstone, swarms of wolf-watchers began descending on the park and sharing accounts on blogs and Facebook. When they arrived, they were invariably guided by McIntyre, who became the park’s red-cheeked wolf ambassador, partially by watching the creatures every single day for more than a decade.

Blakeslee resists the trap of giving the crackling narrative a central villain. In fact, the book almost never moralizes, instead showing us the obsession stitched deep into its players, from the raccoon-eyed O-Six (named for the year she was born) and Turnbull, the controversial but avowedly nature-loving hunter, to school teachers, federal agents and senators. All of them are embroiled in a generations-long battle to implement competing visions of the West.

The real trick, the one that makes the story worth picking up, is the author’s ability to wrap a complex, contentious issue into a human-sized — or wolf-sized — arc. There is much showing and little telling, especially in Blakeslee’s finely textured passages describing arduous elk hunts, wolf migrations and political fights. It is not a rumination on the wolf in lore and legend as a stand-in for conflicting American values. Instead, American Wolf demonstrates the conflict in a series of interconnected vignettes, all swirling around one exceptional animal and the humans who observe and fight over her life and eventual death.

Jack London, whose writing on wolves is perhaps still the best-known, described the intersection of man and nature in The Call of the Wild: “But under it all they were men, penetrating the land of desolation and mockery and silence, puny adventurers bent on colossal adventure, pitting themselves against the might of a world as remote and alien and pulseless as the abysses of space.”

The wolf, a once-unrivaled predator, then almost destroyed, now tenuously resurgent, is a case study in how we understand the alien world around us.