Amid Record Youth Suicide Attempts, Texas Lags in Prevention Training for Teachers

Despite a 2015 law requiring suicide prevention training for teachers, state officials say they do not monitor or enforce the requirement.

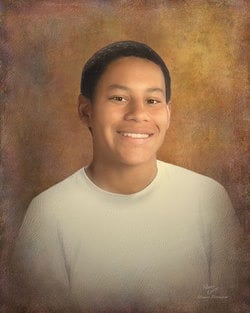

Pretty much everyone at Fairfield High School liked Jonathan Childers, a 15-year-old with kind brown eyes and a wide smile. The freshman played football, lifted weights for the school team and raised animals in the FFA. He had lots of friends. But on the morning of August 13, 2013, Jonathan’s father Kevin Childers awoke to tragedy: Jonathan had killed himself.

“The loss of your grandparents is tough. The loss of your parents is tougher. But nothing can prepare you for the devastation of the loss of your child,” Kevin Childers said in 2015. He told the Observer this month that there weren’t obvious, outward signs his son sought to take his own life. He seemed like an outgoing, well-adjusted kid with a bright future.

Fairfield, a town of about 3,000 on I-45 about an hour-and-a-half southeast of Dallas, is far from the only Texas community dealing with youth suicide. In June, a high school campus in McKinney was locked down after a student died of a self-inflicted gunshot wound at the school. In 2016, an eighth-grade student in New Braunfels took her own life, the possible result of school bullying. A freshman at the Socorro Independent School District in El Paso shot and killed himself in November — bullying was also a possible cause in that death. In 2016, more than 134 Texas teens ages 13 to 17 died by suicide.

Teens in this state are nearly twice as likely to attempt suicide when compared to youth nationally, according to a recent survey by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. When adolescents ages 13 to 17 in Texas schools were asked if they’d attempted suicide in the past year, 12.3 percent answered “yes,” compared to the national average of 7.4 percent. And the problem is getting worse: 12.3 percent is the highest rate ever recorded in Texas since the federal survey began in 2001, up from 10.1 percent in 2013, the last time the survey was conducted.

After his son’s suicide, Kevin Childers, a teacher and football coach at Fairfield High School, sought a solution. With the help of the Jason Foundation, a Tennessee-based group named after teenage suicide victim Jason Flatt, he convinced the Texas Legislature in 2015 to pass the Jason Flatt Act, legislation adopted by 19 other states. It memorializes Jonathan by requiring public school districts and open-enrollment charter schools to train teachers in suicide prevention by looking for and identifying warning signs, such as substance abuse, aggression and self-mutilation.

But now, nearly three years after its passage, Kevin Childers told the Observer that the law is limited in its ability to help curb youth suicide rates. He said the law falls short because the state doesn’t monitor whether Texas’ more than 1,000 school districts are training teachers, and it’s very difficult to independently verify if teachers are completing the training.

Unlike many other states, Texas’ version of the Jason Flatt Act doesn’t require teachers to take suicide prevention training in order to renew their professional licenses. “It’s a state law, but they’re leaving it to local districts to police themselves,” Childers said. “To be honest, I don’t know if that’s working.”

Other states have passed stronger versions. Tennessee, for example, requires teachers to take two hours of in-service training on youth suicide prevention to get their license renewed, as do West Virginia, South Carolina, Alaska and South Dakota. In Arkansas, teachers must take two hours of in-service training on suicide prevention every five years to satisfy license requirements.

A Texas Education Agency spokesperson, DeEtta Culbertson, told the Observer that the agency does not collect any data on suicide prevention trainings, so it’s difficult to know how many school districts have complied. “There would need to be a legislative change requiring this,” Culbertson said.

The Texas Health and Human Services Commission determines which training programs satisfy the requirements of the law, but the agency was given no enforcement authority over the Jason Flatt Act by the Legislature.

“It’s a state law, but they’re leaving it to local districts to police themselves. To be honest, I don’t know if that’s working.”

Brett Marciel, a spokesperson for the Jason Foundation, said “there is no way to know” how many educators are taking suicide prevention courses in Texas. The group “adamantly supports” increasing state accountability, but has “no real means of monitoring” how many teachers have taken the training, he said.

A 2013 state law enlisted local mental health authorities to train teachers and other school employees on “mental health first aid” — a national program that aims to help teachers identify students who are in the grips of a mental health crisis. However, the training isn’t required, and has only reached a small fraction of educators.

About 25,000 public school employees have been trained in mental health first aid, according to state Senator Charles Schwertner, a Georgetown Republican who authored the legislation. That represents less than 5 percent of Texas public school employees. In May, Governor Greg Abbott suggested increasing the number of such trainings in his 44-page school safety plan, a hodgepodge of “school safety” initiatives in the wake of the deadly Santa Fe school shooting. But Abbott didn’t propose making the training mandatory, or suggest new state funding sources.

Now, as Kevin Childers prepares to begin another year of teaching at Fairfield High School, he hopes state officials hear his pleas for greater accountability in suicide prevention training. “In all honesty, I don’t think we’re doing all we need to do,” he said.