The End is Nigh: What Now?

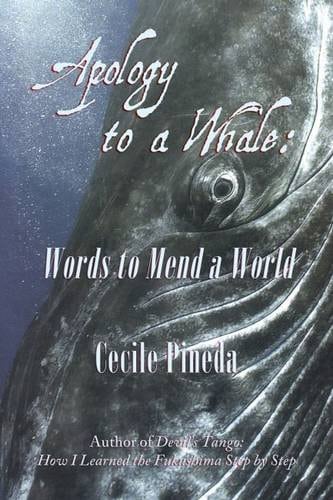

Cecile Pineda's 'Apology to a Whale' describes a disease, and seeks a cure, in language.

A version of this story ran in the October 2015 issue.

Words to Mend a World

By Cecile Pineda

WINGS PRESS

224 PAGES; $16.95 Wings Press

What is an appropriate response to the imminent end of the world?

Well, first, a skeptic might reasonably beg the question, since the world as we know it (according to a variety of sources, some more risible than others) has been on the brink of supposed extinction almost since there has been human intelligence to grapple with the prospect.

On another hand, it may be that skepticism is just another word for denial, and indeed there are few voices making credible claims that all is well on the survival-of-the-species front. Whether it’s resource scarcity, nuclear devastation or climate change that ultimately does us in, there seems to be an increasingly vocal consensus — among public intellectuals, at least — that some cascading environmental crisis or another has our species’ name on it, and that we’re likely to take down a large chunk of the globe’s already shrinking biodiversity on our way out the existential door.

Denial, of course, is the first stage of grief. And I won’t be the first to suggest that grief is the appropriate response to the end — imminent or otherwise — of our world.

For Cecile Pineda, it was nuclear energy and, more specifically, what she calls the “planetary catastrophe” of Japan’s 2011 Fukushima nuclear disaster that sounded the clarion call to awareness and action and set her grief clock to Stage 2: anger. After a storied career as an experimental theater director and play- wright in San Francisco (she founded The Theater of Man in 1969 and directed the company until 1981) and award-winning novelist (Face; The Love Queen of the Amazon), Pineda’s 2012 book, Devil’s Tango: How I Learned the Fukushima Step by Step, marked her first foray into nonfiction. Devil’s Tango hybridized memoir, diary, reportage and spirited pot-banging into a cudgel designed to beat denial into submission. Along the way, Pineda’s clearly restless intelligence was already moving beyond the what into curiosity about the why.

“I am trying to understand,” she wrote, presaging the present volume, “being born to the urge to destroy, to rip mountains apart, to pour thousand-year poison into the seas, to belch soot into the sky, to kill everything that lives. Where does it start, this impulse? In what mind? Where is the axle that turns this wheel?”

As the boil-over rhetoric suggests, Pineda’s project takes impending planetary doom as its starting point, and has little to do with persuasion.

Apology to a Whale seeks that understanding, an explanation for “the pornography of a global civilization determined to rape and mutilate the Earth, which gives us life, and sell her to the highest bidder.”

As the boil-over rhetoric suggests, Pineda’s project takes impending planetary doom as its starting point, and has little to do with persuasion. And good thing, too, because while her passion is palpable, her relationship to facts is much less concrete. For instance: Remember that bogus story that made the Facebook rounds early last year, the one claiming that the Chinese government had begun broadcasting virtual sunsets on giant video screens as an ameliorative consolation for smog-bound residents of Beijing? Just maybe, you thought, that story’s dystopic resonance was a touch too tidy to be true — a suspicion that 20 seconds of Googling would have confirmed. (In fact, Britain’s sensationalist-to-the-point-of-parody Daily Mail had merely and willfully misrepresented a still-frame photograph of a public tourism video as pre-apocalyptic policy.)

Pineda — who refers earnestly to that compelling but entirely false bit of “news” twice in Apology to a Whale — apparently could not be troubled with 20 seconds of Googling. Which is not, of course, to say that everything in Apology to a Whale is wrong, just that her apparent methodology inspires little confidence. And confidence is required of an author who exhibits such unbridled enthusiasm for polymathic synthesis. Otherwise, said author risks finding herself bundled with that most unfortunate class of polymathic synthesizers: proudly unaccredited cranks peddling unprovable pet theories.

At the risk of oversimplifying — a risk the author embraces without acknowledgement — Pineda forwards a theory that the prehistoric invasion of Europe by peoples of the Kurgan culture displaced a preexisting matrilineal and goddess-oriented culture and spread a Proto-Indo-European language whose vocabulary, tailored to the worship of a warlike male deity, favored violence, subjugation and conquest. That language ultimately gave rise to all modern Indo-European languages, including English, the lingua franca of contemporary ecological destruction.

If we set aside for a moment the fact that the “Kurgan hypothesis” is a long-established field of academic endeavor well stocked with controversies and counter-theories, none of which are reflected in Pineda’s offhand historiography, what she’s presenting here is a remarkably plain correspondence: We are violent and destructive because our language is violent and destructive.

“Is it possible,” Pineda asks, “that if we speak a Proto-Indo-European-derived language, English in particular, our language might reflect the legacy of a distant but related culture that denigrated women, that advanced a male sky-god, suppressing worship of the Great Goddess. That embraced warfare and organized itself along non-egalitarian lines? How would that language imprint us? Would our culture privilege all things legendarily associated with the male: hunting, killing, aggression, victory, conquest, brute strength, power, hierarchy, militarism, weap- onry, acquisition, and control? Would it devalue nature, altruism, tenderness, nurture, compassion, conflict resolution, and child bearing?”

Maybe it would. And any student serious about finding an answer — or even someone with a predilection for supporting evidence and enough time to Google — might further ask how that question applies to culturally hierarchical, militaristic and controlling China, whose language does not derive from Proto-Indo-European roots.

But Pineda doesn’t bother to ask. And in her defense, Apology to a Whale doesn’t so much construct an argument as assemble a dog’s dinner of half-baked speculation and foggy dot-connecting that pinballs from the hazards of depleted uranium to hints of 9/11 trutherism to anecdotal explorations of human-animal communication and plant intelligence to contemporary technophobia, Bilderberg paranoia and critiques of the pornography industry cadged from Chris Hedges.

Apology to a Whale is pitched by the publisher as “an urgent reframing of current ecological thinking,” but in fact it reinforces one of the oldest frameworks known to man: paradise lost. The pre-contact Iroquois were “more enlightened” than we are; we’ve lost touch with our “original self ”; poets and children may still access “minds uncluttered by the distractions and detritus of so-called ‘civilization.’” This is an essentially Christian critique that describes an Edenic fall from grace, and Pineda’s quarry is the sin that predicated the fall. Where did we go so wrong?

That’s a comforting question in times of uncertainty and grief. It suggests the possibility of an answer and, just maybe, with the proper penance, a reclamation of grace. And Pineda does finally provide a prescription of sorts, which largely amounts to a call for more mindful attention to the violence and injustice that is indubitably embedded in our language.

That’s doubtless a worthy goal, as far as it goes, but it doesn’t go far. Bargaining is only the third of grief’s five stages, and any appropriate response to the end of the world as we know it will need to start with acceptance.

It would be churlish to criticize the grief-stricken for the state of their progress, or lack thereof, through its long and lonely stages, especially when their grief is one in which we all share. But whether such suffering has anything useful to offer in the sharing is another question entirely.