As the Power Grid Wavers Again, Texans Are Still Recovering From the Winter Storm

Experts say the energy reform bill signed by Governor Greg Abbott doesn’t go far enough to protect Texans from future blackouts.

This article was produced through the NPR NextGen/Texas Observer Print Scholars program, a new collaboration designed to offer mentorship and hands-on training to student journalists and recent graduates interested in a career in investigative journalism.

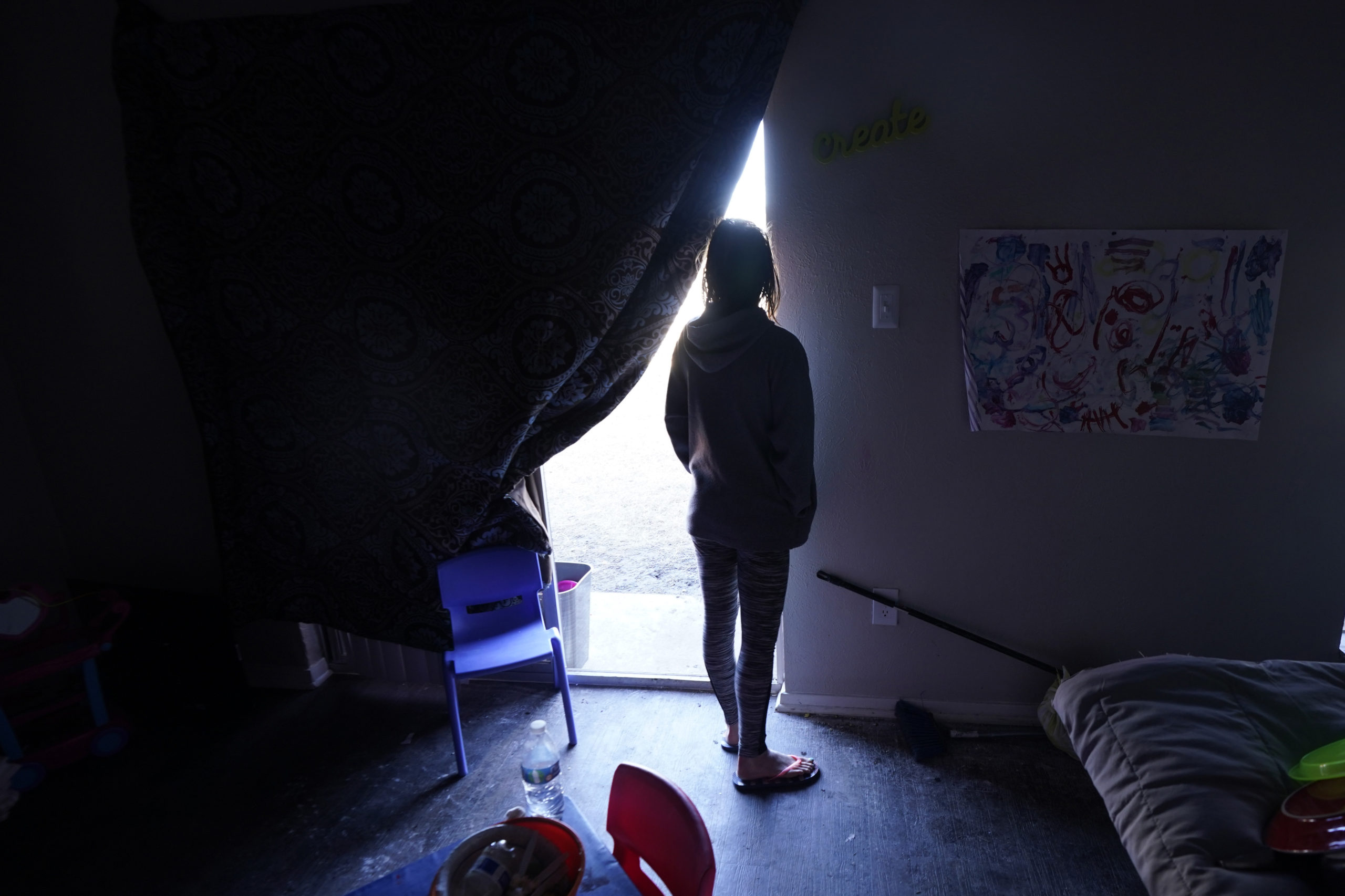

Four months after Winter Storm Uri, Carolina Lopez-Herrera is still putting her house back together. She is one of millions of Texans who lost power and water for days during the record-breaking freeze this February. As the frigid cold set in, her tiny cat, which she and her sister had rescued from a dumpster weeks earlier, stopped moving. Pipes and the water heater burst, causing damages costing more than $50,000. In the aftermath, she’s had to remove walls, replace the water heater, and gut the cabinets and floors. Lopez-Herrera, a 20-year-old paralegal and student at the University of Houston, has been struggling with getting reimbursements from her insurance company and keeping track of the contractors still working on the house. The disruption caused her 18-year-old sister, Susana, to move to California to stay with their father while the house is being repaired.

This spring, frustrated with how her life was turned upside down by the power outage, Lopez-Herrera testified at the Texas Capitol about her experience in support of an energy efficiency bill. She urged lawmakers to implement energy efficiency programs so that homes do not lose power in the event of future storms. The bill did not make it out of committee.

Of the bills that passed this session, Senate Bill 3 is touted as the one that prepares Texas for future extreme weather and winter storms. On June 8, Governor Greg Abbott signed SB 3, saying that “everything that needed to be done was done to fix the power grid in Texas.” The final version of the bill is expected to pave the way for the Public Utility Commission of Texas (PUC) to enforce weatherization at critical facilities. “The power grid is more secure, more robust, and safer than ever before,” Abbott said after signing the bill. But experts say the reforms don’t go far enough in fixing the grid, and while SB 3 details how power plants will be regulated, it fails to help homeowners save themselves—and their homes—from future disasters. On Monday, just a week after Abbott signed SB 3, the Electric Reliability Council of Texas (ERCOT), which manages the state’s grid, issued a week-long conservation alert to Texans during a not-abnormally hot summer day. Natural gas power plants were forced offline for repairs, leaving little room for error as the grid operator once again struggled to keep pace with electric demand.

This year, legislators decided to increase the budget of the PUC by more than $1.5 million. But that extra money won’t give the agency enough teeth quickly according to Doug Lewin, president of Stoic Energy. He says the bill also does not provide homeowners incentives to make their homes more energy efficient. Instead, the bill focuses on the supply of power, which is only half the problem, Lewin says. The other half, the demand-side catering to homeowner needs, has not been addressed fully; energy-efficient solutions should have been a part of the bill, he says.

The bill also gives regulatory agencies broad leeway to levy fines against operators who don’t comply with new weatherization rules. But in some cases, those fines might be less than the cost of weatherizing power plants. For example, during three days of the February winter storm, an operator who hadn’t weatherized might incur $5,000 in fines a day for a total of $15,000, whereas weatherizing a well costs up to $50,000, says Virginia Palacios, the executive director of Commission Shift, a non-profit advocating for changes at the Texas Railroad Commission.

“As always, implementation and execution is different than the adoption of legislation, so we’ll all need to watch and make sure that those things get done,” Lewin says. “We of course systematically underfund our state agents, and our Public Utility Commission is no exception. … The solutions that could have been deployed that would have put us in a better shape to handle the outages in February, the PUC couldn’t get to because they’re underfunded.”

When the ice and snowstorm hit, Lopez-Herrera thought she was prepared. She and her sister did not take the alerts from their university or their family too seriously because their house is across the street from a grocery store, with four gas stations nearby. “We rationalized: We have electricity, it won’t be that bad,” Lopez-Herrera says.

But the single-digit temperatures across Texas caused power plants to malfunction; nearly all types of energy production struggled to keep pace with the astronomical demand for heat across the state. Natural gas production in particular dropped sharply as the product began to freeze in pipelines and in gas wells that weren’t designed to withstand the freeze. Blackouts persisted across Texas, leaving millions in poorly insulated homes that became colder by the minute.

By the third day without power, Lopez-Herrera and Susana spent all their time in bed. They were barely able to eat; experienced horrible, brain-splitting headaches; couldn’t stop shivering; and lost some sensation in their limbs—all signs of hypothermia. Desperate to save their cat, Lopez-Herrera cut a cotton sock and slid it on the cat’s belly for warmth. The cat meowed, the sock warmed her up, and she survived.

The storm killed at least 151 Texans, mostly from hypothermia, according to numbers released by the Texas Department of State Health Services. A BuzzFeed News analysis estimates the true death toll to be more than four times higher. In 2011, a similar cold plunge caused rolling power outages, property damage, and death. Many of the energy industry’s failures were preventable: If they had invested in weatherization—for example, insulating gas wells and implementing better maintenance checks—energy production would not have failed so spectacularly, according to a 2011 federal report on the outages.

Like Lewin, Palacios, and other energy experts, Lopez-Herrera, who has read the language of the energy bill and has been following the issue closely, says she doesn’t think that SB 3 addresses the root cause of the issue. The bill does not ensure that Texans would be saved from the extreme conditions brought on by power outages in the future. If gas wells freeze again, her power might go out and her pipes might burst again, too.

Lopez-Herrera says that to make such extensive repairs to her home again would be horrible. “One time would be enough for me, but a second time in less than five years would age me, and I am 20,” she says. “It would be so hectic and stressful to go through this again. I hope I don’t have to, but [if] it must happen I prefer it to happen to me than to a young family or elderly couple.”

This program is made possible by gifts from Roxanne Elder in memory of her mother, journalist and journalism teacher Virginia Stephenson Elder, Vincent LoVoi in honor of Jim Marston and Annette LoVoi, and other generous donors.