At Home in the World

Houston artist Prince Varughese Thomas blurs boundaries of politics, medium and identity.

–

by Michael Agresta

April 8, 2019

As a young kid growing up between Texas and India, Prince Varughese Thomas was at first blissfully unaware that he was perceived as an outsider in Dallas-area public schools. “As a child, you don’t think of yourself as outside of anything, until things are projected onto you,” he says.

That changed during the Iran hostage crisis, which began in 1979, when Thomas was 10. Suddenly and much to his surprise, he found himself on the receiving end of regular after-school beatings. Thomas was astounded that his classmates couldn’t tell the difference between India, the land of his ancestry, and Iran, but explaining that did nothing to stop the bullying. It didn’t help that Thomas had actually been born in Kuwait, the son of Christian, Malayalam-speaking guest workers from India’s southern Kerala state. Having failed to grasp the most basic geographical distinction, his classmates couldn’t parse all those layers of difference.

Today Thomas, 49, is able to reflect on his childhood tormentors with grace. “In the difficulty of all that, there’s a beauty in how one’s eyes are opened,” he says. “That’s the moment I started just looking.” He’s sipping late-morning coffee in his studio off North Loop in Houston, surrounded by stacks of prints and packing materials for three new Texas exhibitions in 2019. Among those is a show opening April 11 at Asia Society in Houston, and another at Beaumont’s Art Museum of Southeast Texas in the fall.

The same year the hostage crisis began, Thomas received a Kodak Instamatic camera for his 10th birthday. He began taking photos and sending them away to be developed in mail-order envelopes he found in the Sunday newspaper. From then on, wherever he was — including several school years spent in Kerala, where he also often felt like an outsider for reasons including religion, skin color and American education — Thomas was taking pictures. “I got hooked on the act of seeing,” he says.

Thomas’ practice today goes far beyond documentary photography, including sculpture, installation, video art and digital art. His themes are equally wide-ranging, from memorials of misguided U.S. militarism to critiques of news media and personal investigations into family history and mourning. “I’m moved and affected by those places and cultures where injustices happen, separations happen, the demarcations that are based in privilege happen,” he says. “Because of my own life experience, that’s where the antenna goes up for me.”

Given his background and diverse interests, it can seem as if Thomas is coming from nowhere and everywhere at once. He’s a third-culture kid who grew up with an affinity for anyone caught on the wrong side of power, as well as a desire to start deep conversations about differences of all kinds. But Thomas is at the same time distinctively Houstonian. Houston is, after all, a proudly international city, by some measures the most diverse in the nation, with a relentlessly forward-looking attitude and a fraught relationship with both U.S.-oil-driven foreign policy and climate change.

Thomas has also shared in the city’s recent hard luck, losing about one-quarter of his work when his storage space flooded during Hurricane Harvey. Though the loss was brutal, he has recovered with help from the local arts community and a can-do attitude that matches that of his adopted hometown. For someone who grew up an outsider, it’s uncanny how much Thomas has come to fit in with Texas’ biggest city.

–

Thomas likes to point out that, unlike the many Asian immigrants who enter the United States through the East or West Coast, he first came to the country as a 3-year-old with his parents on a transatlantic flight direct to Houston. “It’s like that old saying of ‘I wasn’t born here but I got here as quick as I could,’” he says.

His mother, a nurse, was welcomed due to a nursing shortage, and his father found a job in sales for a forklift company. The family moved back and forth between the village of Othera in Kerala and the Dallas-Fort Worth metroplex on an almost yearly basis until Thomas’ sophomore year in high school, when they settled in Irving.

Thomas’ parents initially encouraged him to pursue science in school. After bouncing from major to major at the University of Texas at Arlington, he finally enrolled in a photography class during his senior year and realized that, in his words, “This is where I should be.”

Thomas stuck around Arlington an extra semester after graduation just to take additional photography classes. Then, in 1992, he followed a girlfriend to the University of Houston for his master’s in studio art, begging his way in despite an initial rejection and a portfolio that he admits was underdeveloped. He attributes his lifelong interdisciplinary approach to his outsider status within art school as a latecomer who never bothered to learn the rules. He moved away from documentary photography and into the then-Wild West of digital art, which at the time was viewed with skepticism in the art academy.

“I’m moved and affected by those places and cultures where injustices happen, separations happen, the demarcations that are based in privilege happen.”

A risk inherent to digital art is that it uses technologies that may become obsolete, going the way of the 8-track or the VCR. For Thomas, however, it just made sense for the political statements he wanted to make. “The idea dictates the medium,” he says. “For me, art is made in specific times, specific places, specific instances. In all my projects, really, I’m just commenting on the now.”

Before his Harvey horror story, Thomas lost a digital body of work when a hard drive crashed in the early 1990s, and he has made art involving digital technologies, such as QR codes, that are now outdated. But other digital projects helped build his reputation after graduate school. Among these were “InterSect,” a series of diptychs of archival family images from India and images from U.S. pop culture, and “Fashion Accessories,” a series of images evocatively depicting real and fanciful “designer drugs” — “For Weight Loss,” “For Penile Enlargement,” “To Trust,” “For Regret ” — set off against lists of side effects.

Thomas has oscillated between works that explicitly reference his Indian heritage and others rooted in a desire to speak broadly as an American or as a global citizen. He acknowledges that it might have served his career better to focus solely on his differences, but he has quietly resisted art-world tokenism. “I can’t tell you the number of times … [that] I have had studio visits with curators who tell me in so many words, ‘You, Prince, should be making work more directly about your Indian-ness,’” he says. “Discounting, one, that whatever I make is formed by that experience to begin with and, two, that somehow I as a person of color don’t have the authority to speak about anything other than that. That type of wall I’ve had to push up against throughout my career.”

Two of Thomas’ best-known works, “K.I.A.” and “Body Count,” on display at Asia Society in April, take a global view. Both deal with the carnage of the long U.S. military campaign in Iraq. Thomas, who commutes to Beaumont to teach art at Lamar University, was inspired to begin the work after meeting with a former student who had dropped out to go to war after 9/11. Back then, Thomas had counseled him to finish college and join the Army as an officer, advice the student ignored.

“He was this quiet, shy little young man, but talented as shit,” Thomas recalls. “He comes back and he wants to visit me. So I see him, and he just changed so much. I mean, he was just a stone. He did his four years and then came back, and it was striking — the person that was to the person that is.”

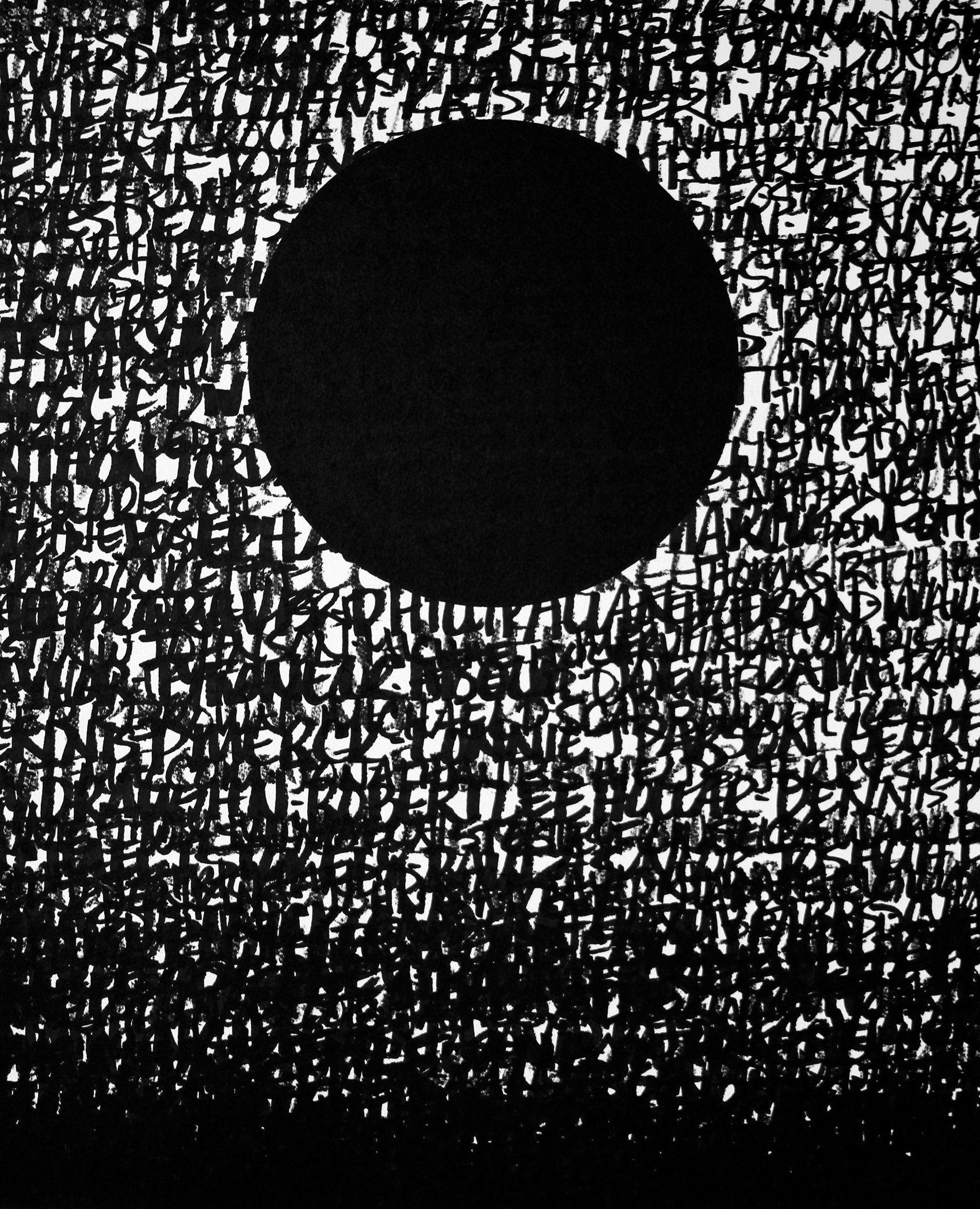

The experience brought home to Thomas how little he and his fellow Americans — he was in the process of becoming a citizen at the time — knew and felt of the traumas unfolding in Iraq and Afghanistan. To try to wrap his mind around the loss, Thomas conceived of two projects. One, “K.I.A.,” is an ever-denser, increasingly abyss-like listing of U.S. servicemen and women killed in action in Iraq. Their names are inscribed in black charcoal, side by side and eventually on top of one another inside a series of shapes, one for each U.S. state. As the shapes fill in and the names become illegible, the piece turns into a commentary on how we numb ourselves to tragedy as it grows in scale. “That piece is about the dead meeting the dead,” Thomas says.

The companion piece, “Body Count,” attempts to convey the much greater number of Iraqi civilians killed as collateral damage in the chaos unleashed by the invasion of Iraq. In 2012, Thomas collected 109,107 pennies, painted them white and glued them in stacks of 25. Arranged in rows on a large, room-dominating table, the stacks quantify in hard currency the innocent dead, based on numbers and names compiled by the Iraq Body Count project.

For his Asia Society show, Thomas has updated both works with names and pennies for those who have died in Iraq since 2012, including 80,000 new civilian casualties. “Just seeing the vast numbers of lives that are affected, I hope hits you like a slap in the face,” Thomas says.

–

Since 2014, the year Thomas’ father died, much of his work has dealt with grief. His January 2019 exhibition at Hooks-Epstein Galleries, “The Light of Other Days,” builds on this preoccupation, combined with his longtime interests in critiquing news media and pointing out instances of global injustice.

Sixteen years ago, when he was 34, Thomas helped his ailing parents move from Dallas to Houston to live with him. Ever since, he has been a caretaker as well as a teacher and an artist. Now married, Thomas still lives with his mother, who comes to the studio with him most mornings at 6, reading the newspaper or watching Malayalam television programs while Thomas works on his art.

After his father’s death, Thomas didn’t create anything for months. When he did, his works were uncommonly emotive, including a 2017 series called “The Space Between Grief and Mourning,” charcoal drawings depicting instances of public and private mourning from around the world, many of them tied to endemic 21st-century problems like mass shootings, terrorism, displacement and environmental tragedies. In “The Light of Other Days,” Thomas toyed with these images, reducing them to black-and-white halftone patterns (the dots that make up grainy, old-fashioned newspaper pictures), and further abstracting them by choosing a single detail and magnifying it. The result, which should speak especially to those of us who have been riding the emotional rollercoaster of the news cycle in recent years, is a meditation on and reflection of the ways we share and express grief for a world in deep distress.

Thomas revisited the images from “The Space Between Grief and Mourning” in part because he lost several drawings from that series to Harvey’s floodwaters. Thomas lives and works near White Oak Bayou; until Harvey, he kept his old work in a storage unit near the bayou as well. His home and studio were spared, and he assumed the storage unit had been, too, until he went to check on it. He opened the door to find that his paintings, photos and sculptures had been sitting in 2 feet of standing water.

“To be honest with you, I still can’t speak about it,” he says. “It was just like, ‘Holy shit, that’s your life. Everything I ever made is in that storage unit.’ It was horrific.”

As is the case for anyone who lost property or items of sentimental value during Harvey, it’s hard to quantify Thomas’ loss in dollars. He received formal assistance from Fresh Arts Houston, Houston Arts Alliance, Jerry’s Artarama and the Joan Mitchell Foundation, as well as informal assistance from friends and peers across the city.

“For me, art is made in specific times, specific places, specific instances. In all my projects, really, I’m just commenting on the now.”

Thomas remains, like his city, focused on the future. He’s excited about his upcoming fall show, which will fill the entire Art Museum of Southeast Texas with new drawings, photos, video and sculpture collectively titled “The Legacy of Narcissus.” It’s still in progress, but Thomas teases that it will involve linked critiques of the Trump administration, social media and the narcissism required to be an artist.

To the extent that Thomas allows himself to think back on Harvey, he avoids wallowing in regret. Instead, he prefers to remember the ways that his wife, his friends and the arts community of Houston rallied to help him move his archive into temporary storage, save what he could and get on with his work.

“That’s the beauty of us as a culture, and this goes for our entire region — the moment tragedy happened, everyone was there to help each other out, without hesitation,” Thomas says. “It was, ‘Yes, I’m there for you.’ For all of our divisions, all our hateful talking towards each other, those moments show us who we are.”

Top image: “Pyongyang, North Korea: December 17, 2011,” from “The Space Between Grief and Mourning” series