Austin PD’s Bad DNA Analysis Nearly Cost This Man His Life

Billy Faircloth was sentenced to 60 years in prison, but an appeals court overturned his conviction.

A team of attorneys working to right the wrongs of the Austin Police Department’s (APD) failed DNA lab recently secured their second win.

On March 29, the Court of Criminal Appeals—the state’s highest criminal court—overturned the conviction of Billy Faircloth, who was sentenced to 60 years in prison for aggravated assault with a deadly weapon in 2012. The state’s case against him relied on bad DNA analysis—a rampant problem in Austin under the regime of the defunct APD DNA lab.

“[Faircloth] contends, among other things, that unreliable DNA evidence was relied upon to secure his conviction,” the court’s opinion states. “The state and the habeas court both agree that he is entitled to relief.”

Faircloth is the second person to have their conviction overturned due to the DNA lab’s mistakes. Lamarcus Turner, who was exonerated in 2022, was the first. He was convicted of drug possession in 2015 and sentenced to 10 years in prison after a DNA analyst tied him to two bags of cocaine police found, saying there was a 1 in 565.6 million chance the DNA on the bag belonged to someone else. A later retest revealed the sample was actually inconclusive—there was no way the analyst could have been as sure as she claimed to be.

The Forensic Project of the Capital Area Private Defender Service—funded in part by an agreement between Travis County and the City of Austin and in part by the U.S. Department of Justice—consists of 10 employees: mostly attorneys, with one investigator and a paralegal. The team is at the forefront of assisting people who were convicted of non-death penalty offenses who may have been affected by the lab’s mistakes, according to Stacie Lieberman, director of post-conviction programs for the Capital Area Private Defender Service.

“It’s important to point out the Herculean amount of work by the defense team that goes into one of these cases,” Lieberman said. “It is not like you see on TV, where somebody discovers somebody is innocent, and the next day they get out.”

The Forensic Project fought for Faircloth’s conviction to be overturned. Travis County District Attorney José Garza supported the defense’s concerns about the accuracy of the DNA analysis.

Although he maintained his innocence, Faircloth was convicted of the February 2011 attack on a 62-year-old woman in an Austin parking garage.

The woman had gone to her car in the employee parking garage at 100 Congress Avenue around noon to take a nap, according to court documents. About an hour later, she began walking to the elevators to go back to work. She was then struck in the head with an object she said felt like a brick. She turned around, and while the attacker hit her several more times, she noted he was wearing a yellow shirt. Two bystanders heard her cries for help and came to her aid, getting building security to call the police. The attacker then fled from the scene. Later, police arrested Faircloth in the parking garage, saying his clothes matched descriptions of the attacker’s.

A worker found a rock in one of the parking garage’s stairwells and handed it over to police, thinking it might’ve been the weapon used in the attack. Police also found a cigarette pack on the ground near the scene of the attack. These two pieces of physical evidence would prove crucial to the state’s case against Faircloth: The state used DNA to put Faircloth at the scene of the crime and put the alleged weapon in his hand.

“It is not like you see on TV, where somebody discovers somebody is innocent, and the next day they get out.”

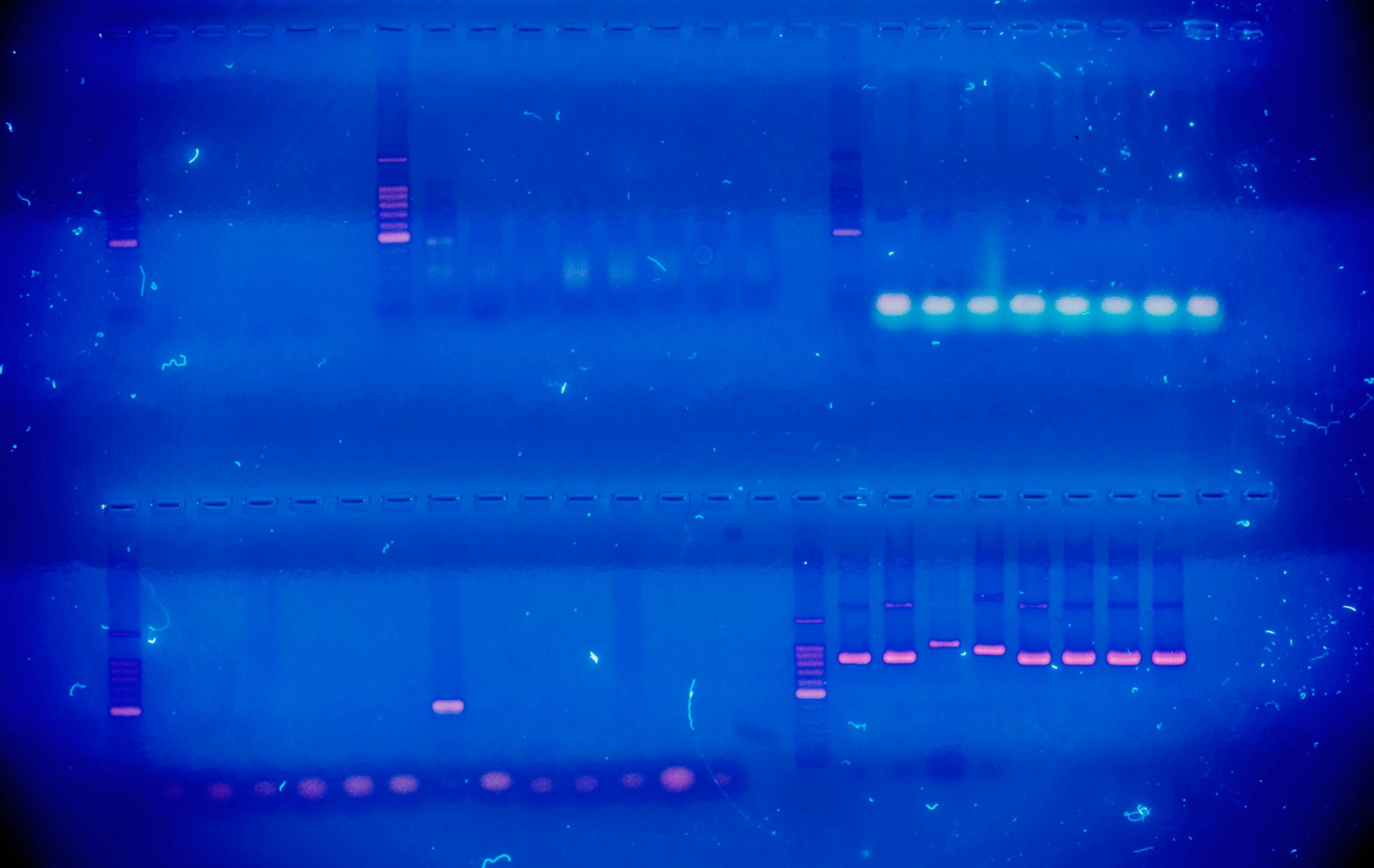

A DNA analyst at the Austin lab tested the rock for touch DNA and found that Faircloth “could not be excluded as a handler of the rock.” The lab also couldn’t exclude him as the source of the DNA on the cigarette pack. But it was later discovered that officers had transported the cigarette pack in Faircloth’s own shoe, a breach of protocol that could have contaminated the sample. And that was just the beginning of a cascade of problems.

In 2016, the Austin Police Department’s DNA lab was exposed for eschewing scientific rigor, and its DNA analyses—including the one that sent Faircloth away—were found to be wholly untrustworthy.

A July 2016 report from the Texas Forensic Science Commission, which performed an outside audit of the lab, found that not only was the lab not using the accepted methods of testing DNA mixtures—meaning samples that might’ve come from more than one person—they were using a seemingly made-up method that had no scientific basis. Auditors found that it was completely ineffective in more than one-third of the cases reviewed.

“Though the process of DNA typing is based on sound science, a degree of subjective interpretation is required when analyzing DNA profiles containing multiple contributors,” the report says.

This subjectivity was heightened when auditors discovered that analysts were letting the samples from the suspect or the victim determine how they interpreted the DNA from the evidence. In some cases, data points were left in that should have been excluded in order to make the profiles a better match. “This approach, commonly referred to as ‘suspect driven bias’ was observed in the casework generally and was not limited to a particular analyst or analysts,” the report reads.

The lab also bungled at least one sexual assault investigation through cross-contamination of the evidence.

In Faircloth’s case, the DNA evidence was the meat of the case against him, as no witnesses to the attack could positively identify him. His defense filed documents with the Court of Criminal Appeals in November 2022.

Jane Eggers, an attorney with Capital Area Private Defender Service, led Faircloth’s release efforts. She came onto the case in 2019 and said the Travis County DA’s office’s support was a boon. “It’s uncommon in post-conviction for the DA’s office to agree on a ground for relief,” Eggers told the Texas Observer. “We appreciate the DA office’s recognition of the problems in the cases that we have brought to them.”

Today, the Austin crime lab doesn’t much resemble its troubled predecessor. Now, the lab outsources its DNA analysis, according to a city spokesperson. The lab’s director, Dana Kadavy, declined to speak for this story.