Author Shane Bauer on How the Racist Roots of Private Prisons Still Permeate the System

“I was struggling with this feeling that I was becoming this different person in prison — a person I didn’t like.”

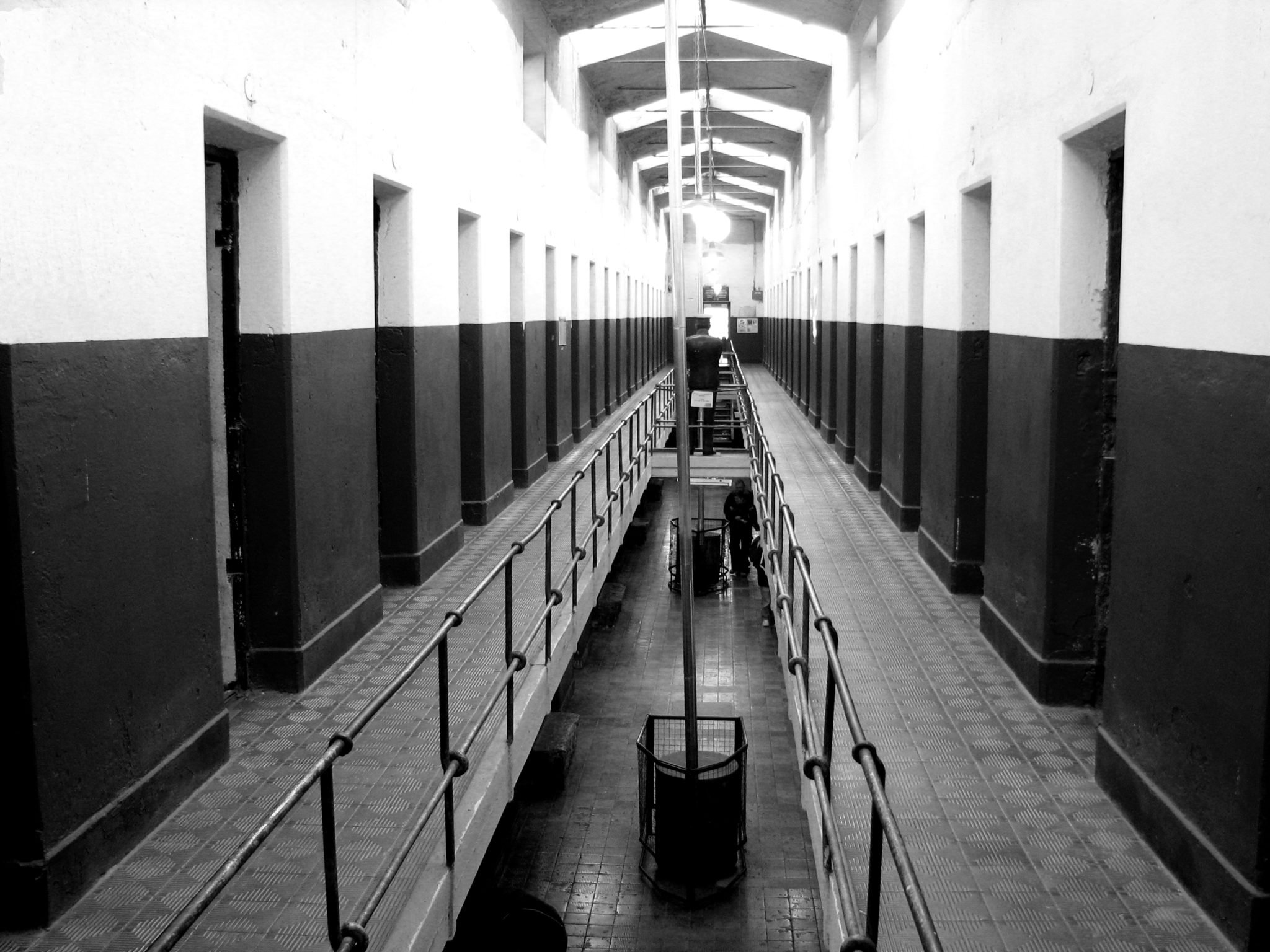

Falsified reports, inadequate medical care, severe understaffing and a plethora of illicit drugs and weapons: These are the grim realities of America’s modern private prison industry. When profit is the bottom line, prisoners’ basic needs often go unmet and any hope of rehabilitation is forgotten.

By Shane Bauer

Penguin

$28; 368 pages

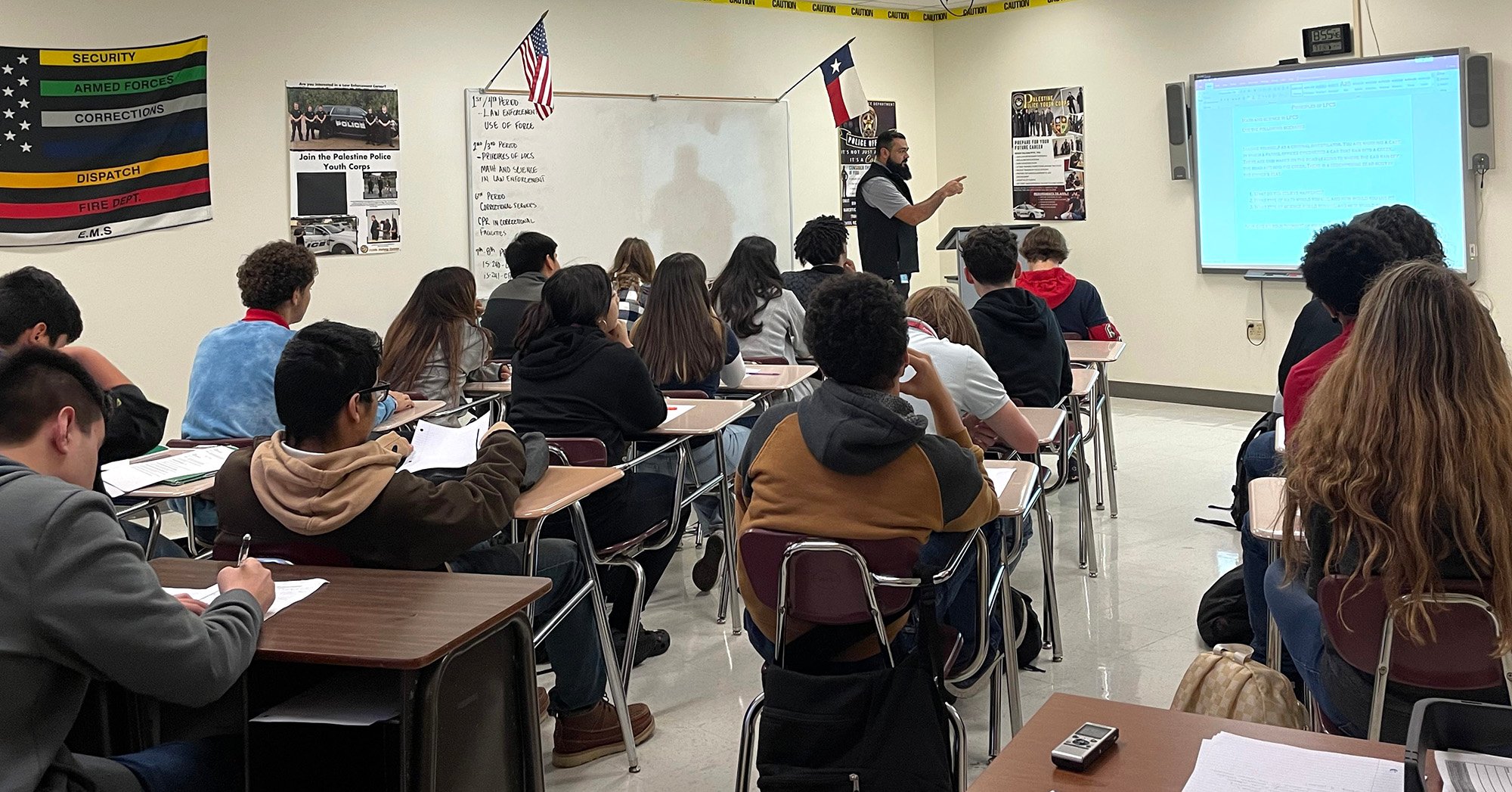

In American Prison, investigative journalist (and MOLLY Prize winner) Shane Bauer explores the history of private prisons in the United States and how their racist roots still permeate the justice system today. The book also expands on Bauer’s 2016 blockbuster Mother Jones story, for which he spent four months working undercover as a guard at the Winn Correctional Center in Louisiana. His harrowing experience offers a rare look into the black box of private prisons, which are notoriously secretive and often exempt from public records requests. From being trained never to say “thank you” to an inmate because it “takes the power away,” to routinely recording security checks that didn’t happen, Bauer recounts myriad failures by overworked, underpaid guards, who were outnumbered by prisoners 176 to 1. He also takes a hard look at how the relentless cruelty of his work affected him, wearing away his capacity for empathy.

You were imprisoned in Iran for two years, and you write in the introduction that some of the conditions you witnessed in Louisiana may have been even worse than your own experiences as a prisoner. How so?

I wouldn’t necessarily say that one prison is better or worse than the other; they’re both really different. The prison that I was at in Iran, protesters were being held there, some were being tortured, people were held in isolation. When left to ourselves, we were blindfolded; we weren’t allowed to interact with other prisoners. It was a highly controlled environment, and Winn was the opposite. It was very out of control, which led to a lot of violence between prisoners. There was a really high amount of stabbings while I was there. In Iran, there wasn’t violence between prisoners, the violence was all from the people in control of the prisons, whereas in Winn, it was so poorly run and the security was so bad that I met prisoners who said that they had carried knives at times to protect themselves.

Besides the loneliness, what was the hardest part of the project?

Working in the prison was really psychologically challenging. I think it was really affecting my mental health and emotional well-being, which is why I was considering quitting, because even though I was getting so much good material, it was really wearing on me emotionally. I was struggling with this feeling that I was becoming this different person in prison — a person I didn’t like. I would just carry so much tension with me that at the end of the day. So I was drinking more, I was having nightmares and I thought a lot about these guys that had worked there for years.

You reference the psychology behind the prisoner/officer dynamic that took place in the Stanford prison experiment and how you yourself started to ease into the power of your authority over inmates. How long did it take for that switch to flip in your mind?

I would say within the first couple weeks on the job I was noticing it. There were things I had to do as my duties as a prison guard that were in competition, in a way, with my identity as a former prisoner. Like I confiscated someone’s cell phone once, and as a prisoner, I would have done anything to get a cellphone. I would have never snitched on another prisoner if they had one, and here I was taking the phone. So there were many ways that I struggled with being on the other side and I felt guilty sometimes for punishing people. I realized pretty early on that I needed to just turn off the part of myself that was struggling with this discrepancy or feeling guilty. And once I did that, the job became a lot easier.

In 1966, an investigation of Arkansas prisons revealed that inmates “were punished for falling behind on their work by official floggings with a heavy leather strap, or by unofficial beatings with hoe handles or anything that was at hand.” How did these brutal state-run prisons lay the groundwork for the rise of private prisons?

This whole system of these state-run plantations had evolved out of an earlier system of convict leasing, where companies were leasing prisoners for their labor and forcing them to work on plantations or coal mines or doing other jobs — essentially filling the role of enslaved people from before the Civil War. States later ended convict leasing but ran their own plantations, running them for decades at a profit to the state.

When [Terrell Don] Hutto was running the Ramsey Prison Farm starting in 1967 in Texas, he did such a good job that he attracted the attention of Arkansas, which eventually hired him to run their whole prison system, which was entirely made out of plantations. Hutto ran that system as a profit to the state. Around the time that he left, in the mid ’70s, the prison population skyrocketed and states could not build prisons fast enough. A couple of businessmen who knew about Hutto and his ability to run state-run prisons at a profit approached him and proposed the idea of starting a company, the Corrections Corporation of America, which would be for-profit. Instead of profiting from prisoners for labor, prisoners themselves would be the commodities. They would essentially build prisons for states and run them at a lower cost.

What were some ways the profit motive played out at Winn?

The main way that these companies cut costs is through staffing. They have lower staff across the board; they had less than [contractually] required while I was there. Less medical staff and mental health care staff — there was one part-time psychiatrist for the entire prison and one full-time social worker. And as a result of this lower staffing, there were all kinds of issues, and the prison was more violent than any in the state.

It also manifests in medical care. I met a man who had lost his legs and fingers to gangrene in the prison; he’d been complaining for months about severe pain in his legs, and they would just give him some Motrin and send him back to his tier. Eventually, it got so bad he had to have his legs amputated. I met a man who I saw collapsing from chest pains, multiple times. He was begging to go to the hospital and they would not send him. The company, by its contract, if it sends a prisoner outside to a hospital it has to foot the bill. So it was reluctant to take on an expense or a hospital bill for a prisoner who is bringing the company $34 per day.

You write that Attorney General Jeff Sessions reversed the Obama-era decision to stop using private prisons, and now it looks as if immigrant detention is the new “frontier of private prison growth.” What do you see as the solution to the private prison method? Do you think private prisons will ever cease to exist?

I don’t know if they will cease to exist, but they should. The only reason they exist is that they’re supposed to save money, but a recent Department of Justice study said the cost of savings were negligible. If these prisons are not being run the way they should be, it’s not just because of the company, it’s because the state is allowing it to be this way, or the federal government or whoever may be in charge of a particular prison. If they’re brought back on track, let’s say to the level of public prisons, they’re not going to be saving money anymore and the whole reason for existing is gone.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.