Babysteps

Can Texas’ new approach to prisoners with newborns help keep families together?

A version of this story ran in the January 2012 issue.

When Isabel Saucedo arrived at Texas’ BAMBI unit on a recent October morning, it was clear this wasn’t going to be a typical prison experience. She was quickly surrounded by four women holding babies. They were laughing and joking. An exuberant energy filled the room, but 21-year-old Saucedo still looked shaky.

Thirty-six hours earlier, Saucedo had delivered her first child, under guard, at the University of Texas Medical Branch (UTMB) in Galveston. Just two hours ago she had been separated from her baby and driven to Houston by correctional officers. Infants cannot be transported with their mothers because the child isn’t a prisoner of the state, and BAMBI—the Baby and Mother Bonding Initiative—is designed to keep it that way.

Thirty-six hours earlier, Saucedo had delivered her first child, under guard, at the University of Texas Medical Branch (UTMB) in Galveston. Just two hours ago she had been separated from her baby and driven to Houston by correctional officers. Infants cannot be transported with their mothers because the child isn’t a prisoner of the state, and BAMBI—the Baby and Mother Bonding Initiative—is designed to keep it that way.

The BAMBI unit for inmates with newborns is Texas’ latest and perhaps most forward-thinking attempt at reducing recidivism and keeping families together. BAMBI operates not at a prison, but at the Santa Maria Hostel, a residential treatment facility for women in northeast Houston. The gated complex of handsome, brick, two-story buildings houses several programs for women as well as BAMBI. Each day, a Texas Department of Criminal Justice (TDCJ) officer drives from a nearby prison and walks through the unit to count the women. Up to 15 mothers and their infants can live here, but there were only seven the day Saucedo arrived.

After the guards removed the shackles from her legs, Saucedo signed in, and a social worker guided her through the outer room, where the electric baby swing was gently rocking a dark-eyed beauty back and forth and two rocking chairs stood waiting. The new mother walked on into the main bedroom, which held four single beds for mothers and bassinets for the babies. Bulletin boards with photos of family and friends hung on the walls. Saucedo’s bed was piled high with baby supplies and a welcome card on top of a handmade quilt. She stared at the women who were all talking to her at the same time. “You can take a shower anytime you want, without asking permission,” Juanita Castillo said. “Or a bath!”

An exuberant pink-faced woman pointed to the courtyard visible through the window: “You can take your baby outside for a walk!”

Saucedo looked doubtful. “We can walk outside?”

A woman in her mid-30s said, “We have group [therapy], every day, and it’s really good.”

Someone remembered it was Thursday and a chorus erupted: “Tonight is pizza night! We get to order pizza!”

Saucedo hugged herself. “Pizza? For real?”

A tall African-American woman put her hand on Saucedo’s arm and said quietly, “The staff here, they treat us like they care about us.”

Castillo ran over to a bowl of fruit sitting on a table and held out both hands, extravagantly framing the bowl. “See this fruit? This is for us! You can eat this any time you want!” That was too much. You don’t get fresh fruit in prison. Tears poured down Saucedo’s face, and she had to take off her glasses, overcome by the over-the top-welcome from the sisterhood of BAMBI.

Saucedo still had one major worry, though, and she turned to Liz Moore, BAMBI’s program manager, to ask about it. Moore said she had just gotten the call that social workers were on their way from Galveston with Saucedo’s baby. Moore then grabbed Castillo and drew her toward Saucedo, putting a friendly hand on each woman’s shoulder.

“Juanita, you are her big sister, to help her get settled and show her the chore list and how the program works. Isabel, this is Juanita, she can answer your questions and help you get settled, okay?”

The two women eyed each other and nodded. Saucedo’s eyes went back to the door.

Ericah Rico—Watch a slideshow of Rico’s last days with the BAMBI program.

The months immediately after birth are a critical time in a mother’s relationship with her child. After the birth, the intense and uncertain process of bonding begins, a process that is increasingly recognized as essential to a successful and healthy life for the baby. Research by a wide range of academics, social workers, doctors, and groups like the Women’s Law Project and the Women’s Prison Association is now emphasizing the need for incarcerated mothers and their infants to stay together to ensure the formation of those maternal-child bonds. That’s the goal of BAMBI: keep the mother and child together, prevent the mother from committing another crime, keep the child from being placed in foster care, and perhaps prevent the child from eventually ending up in prison. A baby born to an incarcerated mother, whether she is in a county jail or a prison, can become a ward of Texas Child Protective Services within 48 hours of birth unless a suitable relative is available to care for the baby. Typically, a female prisoner is returned to her unit almost immediately after giving birth. And it is often difficult for mothers to reclaim children even after short sentences for minor offenses. Termination of parental rights can and does occur. For women who have lived months in dread and depression awaiting the birth and loss of their baby, BAMBI is an unexpected gift. Many call it “a blessing.”

Each year about 250 babies are born to Texas offenders, but only a small percentage of pregnant prisoners qualify for the BAMBI program, which opened its doors in April 2010. In its first 19 months, BAMBI has been home to about 50 babies and inmate mothers.

To ensure security, TDCJ keeps tight restrictions on the program. To be accepted, a pregnant woman must be a non-violent offender serving a short sentence in a state jail, where women typically do time for low-level crimes related to alcoholism, drug use, and property crimes. Nobody convicted of a violent crime, sex offense, or arson is eligible. A common reason for exclusion is physical or mental illness or instability; the program doesn’t have the space or staff to treat mothers with special needs. On rare occasions, another law enforcement agency cuts short a woman’s stay. Isabel Saucedo, for example, was removed by federal officers to face federal charges after just a few weeks in BAMBI; luckily, her husband was able to take their baby home. Saucedo’s early departure was unusual. The overwhelming majority of women stay as long as they can, and many will never commit another crime. Mother-baby bonding programs in other states have significantly reduced recidivism. So far none of the “graduates” from BAMBI have reoffended.

Originally, TDCJ planned to accept only women who had one to six months left on their sentence at the time of delivery, but the agency has relaxed the rules, allowing some with longer sentences to participate. Once in a while, a baby grows to be a toddler before the mother graduates from BAMBI.

TDCJ has relaxed the minimum stay, too. The thinking is that something is better than nothing; even a short stay can bolster parenting skills and ensure bonding. About 25 percent of BAMBI participants are first-time moms.

It was not unusual for U.S. prisons to have nurseries and facilities for mothers until the 1950s and ’60s, when most were phased out. Now, a resurgence of such programs is demonstrating their value. In Nebraska, recidivism is defined as returning to confinement for a new crime within three years of being released. The Nebraska women who gave birth in custody and were immediately separated from their child have a recidivism rate of 33.3 percent. Just 9 percent of the women who went through the state’s nursery program returned to prison.

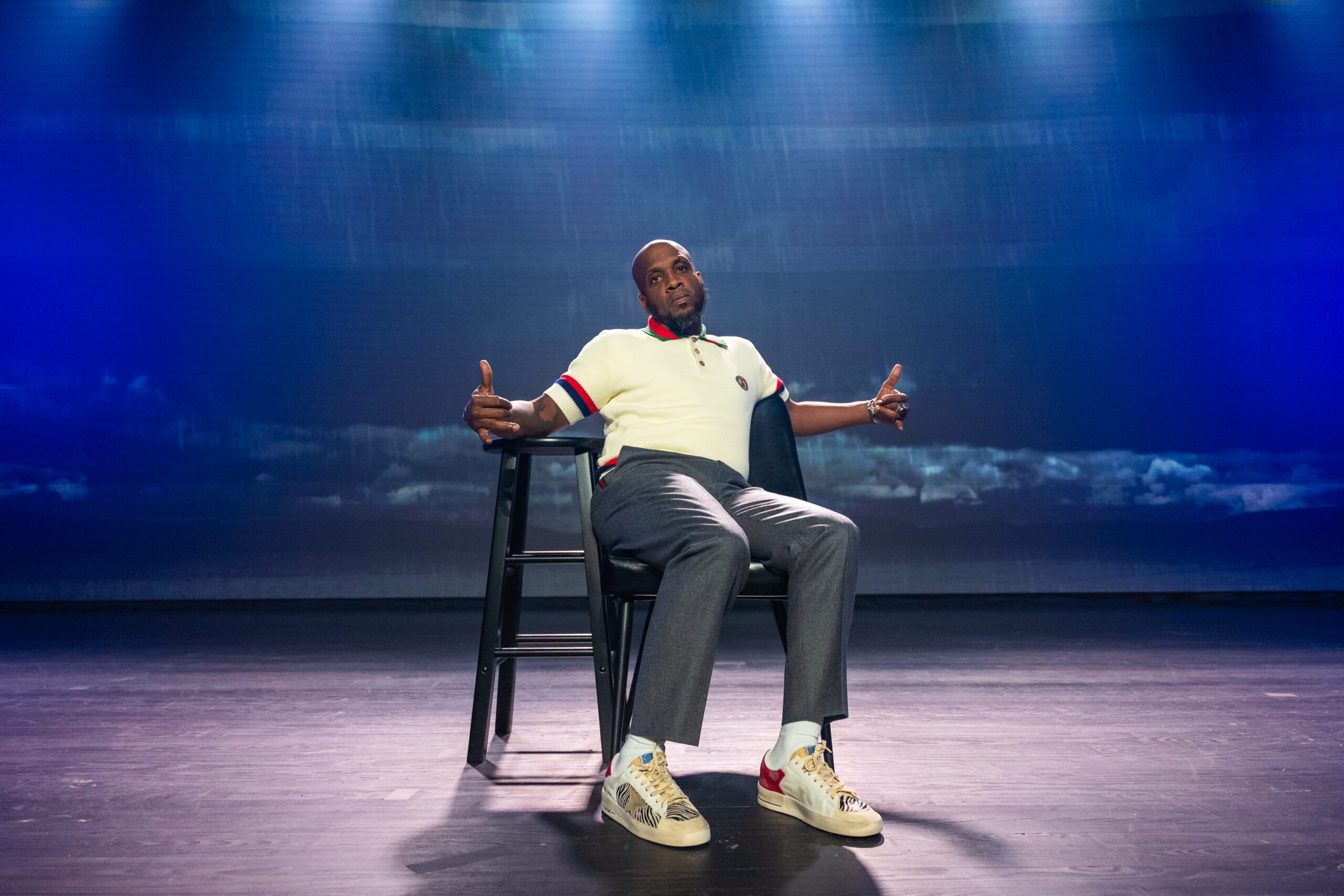

Ericah Rico

Texas hasn’t always been so progressive on criminal justice issues, but skyrocketing numbers of incarcerated women have begun to awaken policy-makers and prison administrators to a new reality. Since 1986, following the introduction of mandatory sentencing for drug offenses, the number of women in prison has risen 400 percent, according to the Rebecca Project for Human Rights. A significant number of those women were pregnant or parenting, and often their family’s primary caregiver.

Prison officials and policy-makers are increasingly aware of how much damage can result from separating mothers and infants. Those who experienced it firsthand, like social worker, advocate and mother Veronica Lockett, said the trauma of losing a mother to prison led her straight into prison as well. In an eloquent letter to then-chairman Jim McReynolds of the Texas House Corrections Committee in 2010, Lockett described how a chaotic family was still a family.

“At 12, my mother’s rights [were] terminated without my consent, and my younger siblings and I were adopted out like slaves during the trade. No one ever asked me if I wanted to see my mother again. No one even asked me if I wanted to visit my mother in prison,” Lockett wrote.

“A mother who drinks or sometimes takes drugs is still the mother of her child,” said state Sen. John Whitmire, a Houston Democrat and sponsor of the bill that created BAMBI. And if that mother could receive intensive therapy and education, he asks, wouldn’t a rehabilitated mother be a healthier role model for the child and possibly break the cycle of incarceration?

Whitmire’s education on the subject began back in 1993, when the hell-raising senator was the brand-new chair of the Texas Senate Committee on Criminal Justice. He was given the obligatory tour of Gatesville prison and was in the midst of asking four inmates questions about their backgrounds. “All of a sudden I realized that this frail little woman was crying. The whole time she was talking to me, she was sobbing. I finally said, ‘Ma’am, what is going on here?’ She said, ‘I had my baby two weeks ago. The next day my family picked him up and took him away.’ She understood that by the time she was reunited with him many months later, he would have become somebody else’s baby.” The realization of how that separation would permanently damage the mother-child relationship hit Whitmire hard. But it would take until 2007 for Whitmire and Rep. Jerry Madden, a Republican from Plano and vice chair of the House Corrections Committee, to pass House Bill 199, which authorized the creation of BAMBI.

Ericah Rico and Araceli

The next challenge was to decide whether to establish a prison nursery inside TDCJ, or to find a location outside jail and create a community-based residential parenting program. Finding the answer to that quandary fell largely on Wanda Redding, a program specialist in TDCJ’s Rehabilitation Programs Division who serves as a department program supervisor to BAMBI.

She researched inmates’ experiences in other states and interviewed administrators of baby-bonding programs. In the end, Redding and the agency decided that a community-based program would provide the best outcomes. The decision echoed the findings of the Rebecca Project for Human Rights and the Women’s Prison Association, which both state that bonding programs outside the prison environment are more successful for both babies and mothers.

Madden said that while it’s still new, the program looks great. But he is also a realist. “The ultimate decision point for me is whether it keeps these women from coming back to TDCJ, and does it keep their children from ever being in TDCJ? Also to see if the mothering skills these ladies are being given result in better families.”

He has visited the Houston facility twice. “I think it’s awesome,” he said.

“BAMBI is nothing like what you hear it is back at Dawson or Plane State [units],” says Angela Allgayer, holding month-old Miley. “People say ‘Yeah, all you’ll do there is hang out with your baby all day.’ They didn’t know about the sharing and group and parenting skills classes.”

The program offers a range of services to ensure that mothers don’t re-offend. Five days a week, the women have a peer-led group therapy session during which they discuss their backgrounds, how they were mothered, their experiences in school, and the abuse and violence in their lives. They also participate in parenting classes, life-skills training, infant-care classes, and a session led by a certified drug abuse therapist plus one individual therapy session a week. That’s 20 hours of programming a week on top of 12-step recovery meetings at night.

Allgayer, now 28, said she had her first child at 15. “I went to TDCJ for drugs one month after my 17th birthday. When I got out that time, I went back to doing drugs and left my son. If I’d had BAMBI back then, I wouldn’t have done all that. I’m learning how to be a better mom.”

She showed a visitor her new baby book. Each mom received one in the class designed to teach parents to read to newborns and to play with babies in a way that builds healthy bonds. Barely taking a breath, Allgayer ticked off other areas of new knowledge. “I’m learning how to use my resources. I’m learning about triggers and warnings signs. The lies we told in our addiction. We have really good groups with a counselor who is an ex-addict.”

Moore, BAMBI’s program manager and herself a licensed chemical dependency counselor with years of experience working with TDCJ, says such therapeutic help is essential if the women are going to change the ways of living and thinking that landed them in jail. And she is seeing impressive results. “This is it—the most teachable moment I’ve ever witnessed,” Moore said. “The amount of change in these moms is huge, and not only that, the babies are healthy and thriving.”

Change is no doubt helped along by a selection process that allows both Redding and Moore to carefully rule out bad candidates, using a balance of discernment and optimism to pick the right women. While a UTMB doctor issues a report on each candidate and other administrators have input, Moore and Redding visit the Carole Young Medical Facility and the UTMB hospitals in Galveston to get to know the women. Moore and Redding make tough decisions on borderline cases, and many are turned away, but once chosen, the mothers soon come to know that Moore and Redding are invested in their success.

The successes are beginning to mount. Kortney Courtney, one of the first inmates admitted to the program, is now in beauty school and sometimes visits Moore, whom she considers a friend and a mentor. As her rambunctious curly-haired son Dylan played hide and seek, the 33-year-old recalled what helped her the most. “I think it was having that support, having somebody in your corner. That makes a huge difference,” she said.

Another BAMBI graduate, Brandee Nichols, recently emailed Redding, “I will always be so grateful to you, Wanda … to Liz and all those that gave me the chance and acceptance into Bambi … it has changed my life!” Nichols is out of prison, has a scholarship, and is studying to become a land surveyor in East Texas.

Remarkably, in the program’s first 19 months, not a single BAMBI graduate has re-offended.

That success hasn’t come easy. The day-to-day life in the program wasn’t always sweetness and light. “Yes, some babies aren’t sleeping,” Moore said, “and all the women have hormones raging so soon after birth, and they’re all getting the first period they’ve had in nine months. They’re all anxious about the future. At the same time, they are getting therapy and anger management and life skills classes. All in 1,200 square feet.”

Out of that complex turmoil has emerged a powerful new kind of community that is keeping new mothers, and perhaps their offspring too, from reentering prison. It’s a community built on a foundation of accepting responsibility and believing in the possibility of change.

“Something special happens,” Liz Moore said. “I know what’s going on in the dorm with these women and babies, but it’s bigger than you or I. Is miraculous too strong a word?”

Austin resident Diana Claitor is a freelance writer who also does historical research and directs the Texas Jail Project.