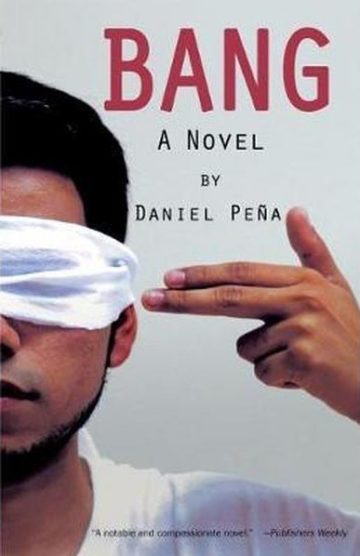

‘BANG’ Offers a Dark Look at the Human Cost of Mexico’s Drug War

Daniel Peña is not sparing in his assessment of Texas, where farmworkers are poisoned by fertilizer and pesticide, and Mexico, where guessing who will be next to die in the drug wars has become a lottery game.

Daniel Peña’s debut novel reminds me of a bantamweight boxer. Lean and compact, it is packed with energy, ready to land blow after punch after jab on any reader who dares to underestimate it.

This story of modern-day Mexico (and, to a lesser extent, Texas) is told through the lives of a mother and her two teenage sons. They are undocumented immigrants who live in a citrus grove outside Harlingen until a plane crash sends them all back to Mexico, separated but with a common goal: finding each other. Each instinctively heads “home,” their hometown in Chihuahua, where they hope to reunite with each other and, perhaps, the head of the family, who was arrested and deported earlier.

By Daniel Peña

Arte Publico Press, Houston

$17.95; 239 pages

Peña, an Austin native who teaches at the University of Houston, offers no new or startling revelations about Mexico and its many layers of law enforcement. We’ve all heard about that. What we rarely force ourselves to think about is how drug trafficking and vast economic inequality alter the lives of even those who never see themselves as part of that crumbling and decomposing system.

They are people like Araceli, always “frustrated with the general situation of things.” Her situation is that she has been left alone with her two sons in a Rio Grande Valley grove, “where the air smells of nosebleeds” caused by fertilizers and pesticides. She fears deportation while hoping — expecting, even — to see her husband reappear at the same roadside location from which he was taken.

Then there’s Uli, her 16-year-old son, a high school track star. He is a maker of lists in his head: of his pains, of the possible fates of his brother, of the foods, bands and girls he loves, and of the things he needs to buy in order to get back to Texas.

Uli’s older brother, Cuauhtémoc, is forced to give up an athletic scholarship and drop out of school three months before graduating. He goes to work with the grove boss’ son, who teaches him to fly crop-dusting planes. Trapped in Mexico, he is forced to fly Texas-bound cartel planes filled with drugs.

Peña is not sparing in his assessment of Texas, where farmworkers are poisoned by fertilizer and pesticide, and Mexico, where guessing who will be next to die in the drug wars has become a lottery game, thriving because “the delinquents” are going to kill each other anyway, so somebody might as well make money out of it.

Peña is not sparing in his assessment of Texas.

Most of the novel is set in Mexico, but Peña uses very little Spanish. Other than an occasional Pos sí, ni modo, the dialogue is almost entirely in English, which is a good thing. The use of a single language, without the need to pause for translation, facilitates the fast pace of the narrative.

There is a sweet economy to Peña’s writing. A confident writer, he doesn’t try to impress the reader with intricate phrases and showy sentences. This is not to say you won’t find striking writing here. Describing the fated airplane’s takeoff, for instance, Peña writes, “The Pawnee gallops over the dirt as haughty and elegant as your average town drunk.”

He describes a cartel safe house this way: “Inside, there’s the too-sweet smell of perfume and sweat. There is the honeyed sound of women’s voices, soft like leather — the lilt of beauty queens or beautiful liars who say they’re beauty queens. There’s the knock-knock-knock of their heels against the tile, tiny women who seem almost weightless as they glide.”

When Cuauhtémoc has sex with these women, “He wonders how many dead men they’ve slept with already.”

Some of the fine writing is harrowing, as when Peña describes in excruciating detail how Uli administers dose after dose of heroin to a badly injured comrade, or when he depicts the collapse of a wall of a long-abandoned church, exposing the degeneracy of long-dead priests.

There is a sweet economy to Peña’s writing.

In a conversation that lays out today’s reality for many Mexicans in both countries, we hear one of Cuauhtémoc’s associates defend, or at least try to justify, cartel life.

“We’re still slaves. Even in Texas, Tucson, wherever,” he says. “We make El Norte run and we bring this country to its knees. But at least there’s some dignity to destruction. Some dignity in living here. It’s nice for a little while, don’t you think?”

The novel, from start to finish, makes it clear that the key phrase is, “for a little while.”

One passage remained with me, hauntingly. In it, Peña describes the scene around the corpse of a slain scrap dealer named Chente:

“Around the scrap yard, the sky is littered with moths that skitter about the light of every glowing thing, even Chente’s teeth, which glow with a hue all their own in the purple whirl of police lights burning bright against his green skin. The moths do not discriminate between the sources of light. They land, two or three of them, on the curl of Chente’s open lip. They gum their wings up in the blood of his mouth and stay there. They drink it. They die in it.”

Substitute “Mexico” for “Chente,” and you get the gist of what this book is about.