Surviving Baptistland

A well-known warrior in the #ChurchToo movement reveals in a new book how she escaped from an abusive Texas home and an abusive Southern Baptist church.

Christa Brown, a former Texas appellate attorney, is revered as perhaps the best-known of the brave women (and men) who blew the whistle on abusive clergy and coverups at churches in the powerful Southern Baptist Convention (SBC). She began her quest at age 51, by bravely sharing her own story of being repeatedly sexually abused as a teen by her youth pastor, Tommy Gilmore, the man she’d gone to for counseling at her church in Farmers Branch. She first came forward as a whistleblower in 2009.

“I think I was ahead of things. That was before #MeToo and #ChurchToo and all of that,” she says. While still running a busy Austin law practice, Brown for years collected and shared stories of others who sought help through the blog and website she set up, StopBaptistPredators.org, which compiled reports on hundreds of abusive clergy and created the first public database of convicted, admitted, and credibly accused Southern Baptist clergy sex abusers.

Brown, now retired and living in Colorado, has continued to lift up other survivors and press for reforms. Her first book, This Little Light: Beyond a Baptist Preacher Predator and His Gang (Foremost Press, 2009), shares her journey from a frightened teen to an outspoken whistleblower. Her new memoir, Baptistland: A Memoir of Abuse, Betrayal and Transformation, out May 7, goes deeper. It is the confessional and sometimes excruciatingly intimate story of Brown’s life trapped in Baptistland, and her harrowing escape.

Brown spoke with Texas Observer Investigations Editor Lise Olsen. Olsen first met Brown when she covered Southern Baptist abuse survivors as part of the Houston Chronicle/San Antonio Express-News team that produced an investigative series called “Abuse of Faith.”

TO: Why did you decide to write a painful memoir that delves so deep into troubling family secrets?

Christa Brown: For me it begins with the stories of so many other survivors that I have heard, and I can’t tell. But I hope that in telling my own story that other survivors see something that will resonate. This is one person’s memoir. But I think sometimes the stories of one person can shed light on history. And that’s part of why I wrote it.

In so many conversations with other survivors, I have [heard] stories of familial estrangement after they speak out and come forward. And that is something many of us don’t talk about much because it is so painful.

As a journalist, I heard stories of the secondary harm caused by the rejection of a clergy abuse survivor’s friends, church members, and family. In your case, you share how you became estranged with all three of your sisters.

Some survivors say that they felt as though they lost their entire community. They lost everything. I’ve heard that countless times.

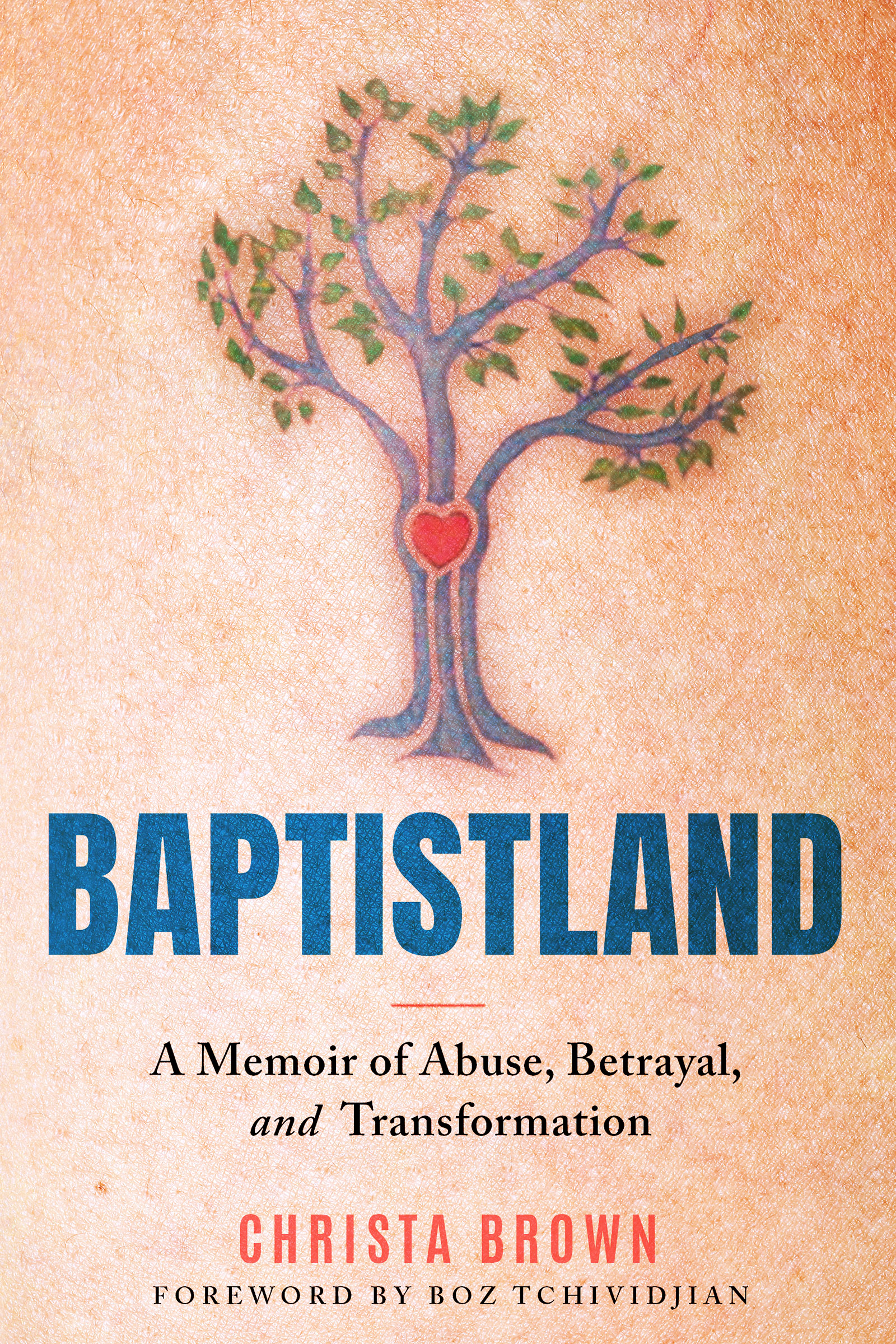

You wrote at times you wanted to “slither out of your skin” as a teen survivor of sexual abuse. Why did you, many years later, put a tree of life tattoo both on your skin and on your book cover?

It is a very open and vulnerable and exposed book. And so the tattoo on my skin, and on the cover of the book is a way of showing that vulnerability. This is a story about a human body. It’s about embodiment, how we live. I think the cover reflects that. But I think mostly what that cover reflects [is how] I’m trying hard in this book to peel back these layers of truth, to reveal something. And that’s a very intimate portrait. The cover also reflects that intimacy.

I know you didn’t get that tattoo as a teen—as a Southern Baptist you couldn’t have. You’d have been in huge trouble. When did you get it?

Many years later in my 50s, when I was dealing with cancer, actually multiple invasive cancers all at once. Intellectually, I know that cancer is a multifactorial process. But at the time, emotionally, I felt that experience as the culmination of all the horror of what I had been through in Baptistland.

One of the things the surgeon said when I was diagnosed was: “Well, this appears to have been growing for six years.” and I counted back, I thought, this began when I was literally trying so hard to get people to do something about my perpetrator, get people in the Southern Baptist Convention to do something, and they threatened to sue me and all sorts of things. I wound up feeling that time was so stressful that my very cells were in rebellion. That’s how I experienced it emotionally. But I’m very healthy now, thankfully.

In your case, your abuser often said “God Loves you Christa,” after assaulting you. Initially, he compared you to Mary, the virgin mother, and later to the devil, after he chose to blame you for his own sins. One startling insight comes when a college counselor later told you that you seemed to be suffering the way victims of incest do. Can you explain how being abused by a pastor might be as damaging to a child as being abused by a relative?

Being abused by a pastor, for someone who has been raised [and] indoctrinated in this faith group as I was, carries with it the idea that “This is what God wants. This God wants your life.”

I mean, that’s pretty all-encompassing. Sexual abuse when it is combined with abuse of faith, combines into something enormously powerful that just eviscerates all aspects of a person, physically, psychologically, emotionally, and spiritually, everything’s gone. Because if this is what God wants of you, what does that say about who you are?

And family estrangement can be extreme for survivors of incest or of pastor abuse, right?

It’s interesting in Baptist churches, we call the pastor “Brother Bob” and we talk about our church family. I think there are a lot of parallels to incest.

One revelation in this book is that your abuser, Tommy Gilmore—despite being the subject of news reports, and a lawsuit that resulted in a formal apology from your church—continued to be employed in his Florida megachurch long after you spoke out. The Texas music minister, who knew Gilmore was abusing you and protected him, remained employed in churches too. Do you see these men as symbols of how the SBC continues to protect abusers and those who cover up?

Absolutely. The same thing is still happening today. After my first book, I thought that after everything I had been through. As painful as it was, I had succeeded in getting Tommy Gilmore, the perpetrator, out of ministry. It was only later that I realized he had only stepped away from being a staff minister, but he was still doing contract work as a children’s pastor. And since he wasn’t a staff minister, his photo and his name didn’t appear on any church website or staff registries.

And same thing with the music minister, who knew and covered it all up. His career went on. No one held against him the fact that he completely turned a blind eye to child sexual abuse. Both of their careers wholly prospered. There was never any consequence within the institution. Never any accountability.

So often we see that abusive pastors target children from troubled homes—is that why you chose to be so transparent about the many problems in your own family? To help others see those patterns and hopefully act?

All children are vulnerable. I think it is the very nature of childhood. But I do also believe it’s true that some children are more vulnerable than others, and certainly those who come from troubled families have more vulnerability. I think they can be targeted more. That was certainly my story.

In this book, you explore generational trauma in your family. The revelations you share about your paternal grandmother being killed (in front of her children) and maternal grandmother being committed to a mental hospital are deeply disturbing. Did you learn those stories while researching this book?

In part. I did grow up knowing that my maternal grandmother lived in an institution. But as a kid, I just didn’t think about it much—about how or why she had been committed. I learned more after my mother died. And I learned about my paternal grandmother’s violent death after the last of my father’s siblings died, when I had some communication from cousins.

In the process of writing the book, I began to put those pieces together, and reflect. Those things gave me enormous compassion for my parents, which doesn’t excuse anything that they did, but does help me see it with new eyes. I mean, when my dad was post-military, we didn’t even have the acronym PTSD. It just wasn’t on the radar for World War II veterans. And so, learning about those things really helped me understand them better.

I know you for your work as a whistleblower, which was critical to our Abuse of Faith investigation and the publication of a database of abusers. For a while, it seemed like SBC leaders would enact real reforms. Instead, as you write, it has turned out to be the “Do-Nothing Denomination.” Do you have any hope at all that the SBC will embrace change after it created a task force, launched a study and published its own formerly secret database?

No. That is something that has changed about me. Once upon a time, I did believe that if only I could show them the extent of this problem and the harm that was being done, surely they would reform. I do not believe that any longer. I certainly don’t think it will happen in my lifetime. I believe they will continue to do as little as possible for as long as possible.

Because I think that for them, the priority is still managing the brand, managing the image, and protecting the institution. I guess protecting kids and congregants is way down on their list.

What we see in Baptistland is, at its root, a theology that is founded on oppression, hierarchy, and authoritarianism. It goes all the way back to the SBC’s roots as slaveholders.

SBC leaders seemed to push harder to expel women who were daring to preach instead of expelling abusers. That seemed to be one of their responses to the tremendous efforts made by survivors as part of the #ChurchToo #SBCToo movement.

This is where they’re putting the focus: on expelling women preachers, and they don’t even have many because they’ve already run most of them off.

Recently, we’ve seen efforts to promote the so-called “trad wife,” with women trying to make the lifestyle where they stay home and cater to their husbands look cool on social media. Why do you think it’s important for more women to escape Baptistland, even if they haven’t been sexually abused?

What we see in Baptistland is, at its root, a theology that is founded on oppression, hierarchy, and authoritarianism. It goes all the way back to the SBC’s roots as slaveholders who protected the interests of other slaveholders. And it comes into the present day with the same sort of rationalizations and justifications for why men should have authority over women.

They don’t want women to have leadership positions in the church. And they adhere to this notion that women should graciously submit to their husbands. It’s not enough to just submit. They want women to graciously submit.

I think, any time you start from a foundation of believing that some people for no reason other than their gender should have authority over others, that necessarily lends itself to abuse.

That’s what we have in the Southern Baptist Convention with their notion that men should have authority over women. And if you combine that foundation with a structure that is wholly lacking in effective systems for accountability, then it sets up a monster of a system in which there is no recourse.

When you tell people that God wants you as women to be submissive to men, that’s an abusive concept. And I don’t think it does men any good either. It doesn’t do families any good. It sets up all sorts of false expectations and harmful expectations. It’s a patriarchy and an authoritarian system.

You write this book as if each part of it was a death—in a way you are harkening back to the Christian metaphor of being born again. Have you truly escaped Baptistland?

I have certainly been born again multiple times because of these deaths that were imposed on me.

I don’t think anyone ever escapes the indoctrination of our childhood. We take steps, big steps, little steps. And certainly I’ve done that, but Baptistland is a part of me. It’s where I was raised. It’s how I was raised. It’s the culture in which I was enmeshed. And I also think that when childhood sexual abuse is prolonged and repetitive, and mine went on for many months, I think that too is something that stays. Yes, we move forward and yes, we still have good lives, but it doesn’t go away. My abuse was a part of Baptistland. That’s still a part of me.

Although I myself haven’t fully escaped Baptistland—and probably never will—my daughter knows no part of it. Baptistland is wholly unfamiliar and alien terrain for her. And that makes me very happy.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.