Race to the Bottom

How Beaumont's racial divisions created the most dysfunctional school district in Texas.

A version of this story ran in the November 2014 issue.

When Carrol Thomas arrived in 1996, Beaumont was struggling and divided.

The Spindletop oilfield, which had made the city rich, had dried up decades earlier. The oil crash of the 1980s stalled business at Beaumont’s port and prompted mass layoffs at its refineries. By the mid-1990s, years of white flight to exurbs along the interstate or north into the Piney Woods had shrunk Beaumont’s population to its lowest levels in 40 years. The civil rights movement, which seemed to take hold in Beaumont long after it did in the rest of the South, had an uneasy effect on the schools, with students riding dutifully each morning on buses from one segregated neighborhood to another, an imperfect but hard-fought alternative to segregation. Racial unease on the school board—largely about whether to continue busing—led to such dysfunction that two state monitors were dispatched from Austin to oversee the district. And then Carrol Thomas came to town promising to rescue the schools.

By 1995 the black community had gained a large share of the city’s population and a slim majority on the school board. After more than a century on the sidelines, African-American Beaumonters finally had a meaningful say in how their schools were run. Thomas was the man they picked to be Beaumont’s first black superintendent. He was a young school-turnaround artist who’d just saved Houston’s North Forest ISD from school board infighting and financial questions that prompted a federal investigation. As a sign of trust in the district’s new leader, the state recalled its monitors from Beaumont a few months before Thomas took office.

After just a few years, city leaders agreed that Thomas had delivered on his promise. The district was upgrading run-down schools in black neighborhoods, and had ended crosstown busing in a fashion that appeased both white and black community groups. With his firm but personable manner, Thomas built cooperation in a city that seemed doomed to wallow in distrust. As one white trustee told The Dallas Morning News early in Thomas’ tenure, “He enabled us to step back and see what was important.” Test scores rose, the district gained a sunny reputation and, perhaps most incredibly, the city itself seemed to be reversing its slow decline. “What he has done to improve the Beaumont school district has probably been the single biggest change for economic redevelopment,” the president of Beaumont’s chamber of commerce told the Morning News. “There’s a lot of movement back into the city.”

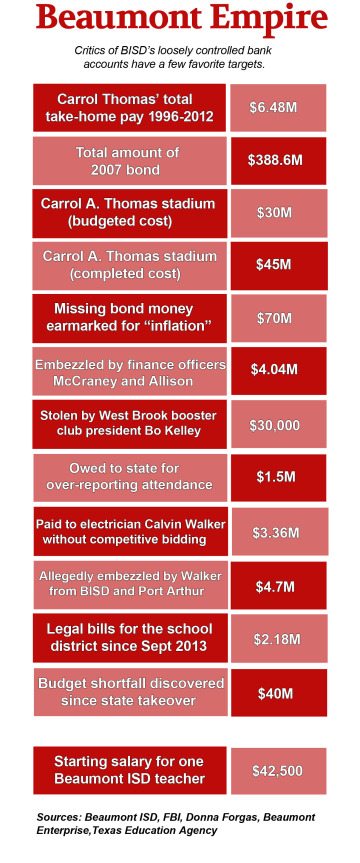

Little of that goodwill remains today. The district’s growth, test performance and financial stability once so celebrated now appear to have been, to varying degrees, illusions. Texas is growing, but neither Beaumont nor its schools are getting much bigger. Carrol Thomas spent 16 years as the city’s school superintendent—an almost unheard-of tenure for urban school leaders—and the multimillion-dollar surplus estimated when he left the district in 2012 has evaporated. Gone, too, are a $389 million bond package, much of it spent on projects that ran over budget, and millions in hurricane recovery funds. In their place, auditors discovered a $40 million budget shortfall, and federal investigators have found millions in embezzled public funds. The state has returned, this time to take over the district to save it from financial collapse. To remain solvent, Beaumont ISD has cut treasured school services like buses from after-school sports, tutoring and dozens of jobs.

Another casualty of the recent scandals is the trust Thomas built between the white and black communities. For a time, he really did bring the city together—Beaumont ISD was a model Texas school district with a visionary school leader. It’s hard to know how much to blame him now, or whether the district was simply destined for another fight. But Thomas’ legacy, far from the bridge-building he promised, is a level of animosity that old-timers say is the worst they’ve seen. By the time the state stepped in last spring, Beaumont had reclaimed its reputation as Texas’ most dysfunctional school system.

“It was kind of an open secret that Taylor had been hired by South Park to fight desegregation.”

A few minutes’ drive west of Beaumont on Interstate 10 stands a great monument to the Thomas era. It is, depending on whom you ask, either a fitting tribute to the man who led the schools for so long or a galling reminder of his excess. At night, the Carrol A. “Butch” Thomas Educational Support Center is a bright island in the darkness of an old rice field, a $45 million complex opened in 2011, $15 million over budget, with the old superintendent’s name easy to spot from the highway, lit up against the sky. (Rumor among Thomas’ critics is that the building’s plans were reconfigured, at some expense, to ensure prime visibility for the name.) “Educational Support Center” is a bit of a euphemism; it’s a stadium, and this is homecoming night for West Brook High School.

On the football field, the players receive their applause like royalty, strolling along the 50-yard line, waving to the crowd as their names appear on a monstrous, million-dollar scoreboard. The homecoming honorees are a racially diverse group, like the crowd itself. An outsider looking for some sign of the racial antipathy the district has become known for would find no clear division between black and white in the crowd. The game ticket features the school’s logo: a grizzly pawing at the West Brook coat of arms that includes an image of two hands shaking. These West Brook Bruins, now racing onto the field through the legs of a giant inflatable bear, are the keepers of a tradition that began 30 years ago with a long-overdue effort to desegregate.

Beaumont’s schools were split back then between two districts: the original Beaumont Independent School District and the smaller South Park ISD in the city’s south and west sides. South Park, the whiter district, remained segregated into the early 1980s thanks in part to its strong-willed superintendent, O.C. “Mike” Taylor. “It was kind of an open secret that Taylor had been hired by South Park to fight desegregation,” says John Kanelis, who was the editorial page editor for The Beaumont Enterprise in the 1980s.

The U.S. Supreme Court had ended official school segregation in its 1954 Brown v. Board of Education ruling, but the local response in South Park was a weak “freedom of choice” policy: Black children could attend a white school if they wanted, but the district wouldn’t encourage them or help them get there. Into the 1980s, Forest Park High School remained almost entirely white, while Hebert High School was all black. In 1983, Ed Moore, a TV repairman who would later become the first black Jefferson County commissioner, explained the approach to Texas Monthly: “The South Park board has waged a calculated campaign to ridicule the federal government and fool the people of this district. I give them credit, they’ve been good at it.”

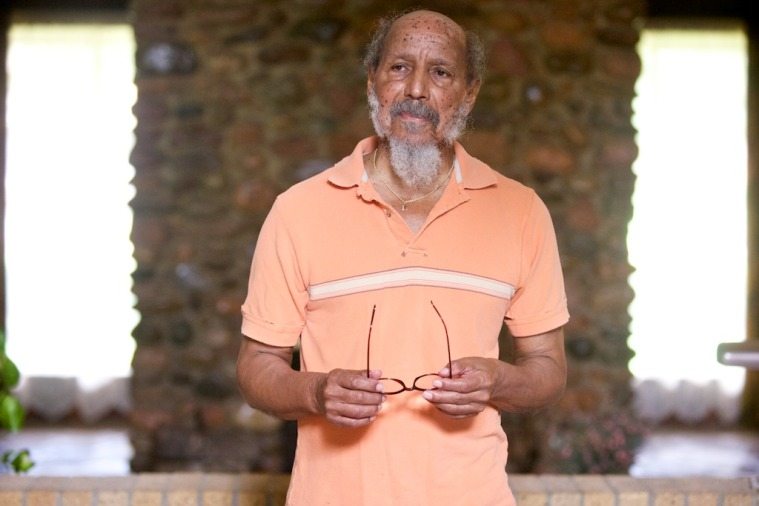

Decades after other U.S. school districts had already done so, and only after a decade of legal wrangling in federal court, federal Judge Robert Parker ordered South Park to draft a desegregation plan in 1981. At the time, the school board had one black trustee out of seven, a Lamar University math professor named Richard L. Price.

Price remembers the majority response was simple: “The board did not want to comply.” He’s sitting in his brick ranch home’s big sunken living room on Beaumont’s west side. He leans back in his recliner, laughing as he remembers how hard the other trustees fought the change. Price was raised in the old Pear Orchard community on the east side, where the South Park district’s first black school was built around the turn of the 20th century. Price’s father was a Baptist pastor and principal of Hebert, the Pear Orchard’s new high school, in the 1950s. (The late state Rep. Al Price was Price’s older brother.) South Park’s administration took little interest in the black schools. Black school principals didn’t follow the white administrators’ career path to the district office, and though South Park was flush with property tax wealth from the chemical plants outside of town, the black schools saw little of it.

Price learned when he was young about the social calculus that went into getting money for the black schools. He’d just returned from the Army and his father was taking him around town. They stopped near a part of the Pear Orchard known as “Tripe City,” where the air stunk of the Zummo Sausage slaughterhouses nearby, and Price’s father said they’d build the new black high school there. It seemed like a terrible idea to Price, but it was on Fannett Road, the main way out of town before the interstate was built. Price’s father explained: “White people are going to support that school because they’ve got to pass by there going to the beach. And surely they want to be able to say, ‘We can make it to Crystal Beach and Galveston Beach, we ought to be able to do something decent for these black people.’”

Price earned a doctorate in mathematics and a master’s in divinity, then returned to Beaumont in the ’70s to teach at Lamar. He saw little had changed in the schools since his childhood. Black school administrators still weren’t getting promoted and the schools for black students remained segregated, underfunded and under-supplied.

Price won a seat on the school board and began gathering hard evidence of the inequity. “My background is mathematics, and I had to have access to the books. I just sat down and studied the books,” he says. White board members, in private, defended their decisions to steer more money to white schools, Price says, and he became an outspoken critic. “I told the board, ‘I am a teacher and I will at least teach my people what you are saying behind closed doors.’” He lasted just one term.

Judge Parker created a plan to break the standoff: Both Hebert and Forest Park would close, and South Park would create a new school in their place to open in 1982. Ninth and 10th grades would be at the old Hebert building, the upper two grades at Forest Park. The name, per a vote by the students, would be West Brook. It was a bold, elegant solution that created countless new conflicts. Two schools meant two principals, two basketball coaches, two football coaches—and room at West Brook for only one of each. Many didn’t see the arrangement lasting long. Federal Judge Joe Fisher put it plainly in Texas Monthly’s 1983 story on West Brook: “There’s no authority that says you’ve got to have more mixing. Black people like to live with black people. White people like to live with white people.”

“There were elements in the white community that thought the earth had just spun off its axis … that the African-American community was going to take over the school district and they’re gonna wreck everything.”

Despite the circumstances, and despite losing four games that first season, West Brook tore through the playoffs to claim the state 5A championship at the Astrodome—the city’s first win at the state’s highest level of high school football in 50 years. Fans and news reporters alike basked in the moment. “We’re here because we were all brought together,” one fan said. “If ever a single athletic event was played for a high and poignant purpose,” the Enterprise’s Mark Lisheron wrote, “West Brook’s win over L.D. Bell of Hurst 21-10 was it.”

But the goodwill from the championship didn’t last, Kanelis says: “It ended on Saturday morning when the game was over.” Even as Beaumont celebrated the state title the West Brook union had given the city, the South Park board was still fighting desegregation in court. The year after the championship, Price was voted out of office and the board was once again all white. The Enterprise editorialized in 1983 that South Park’s trustees were “still seeking relief from the ‘burdens’ of desegregation—burdens that have relieved more than a third of the district’s residents of the historical reality of willful discrimination. If South Park blacks are not inclined to help the district tamper with the court order, it is because the schools their children attend today are so much better than before 1981.”

South Park’s board also opposed another idea that was soon proposed—reviving a plan South Park had spent decades fighting—to unite the city’s school systems. South Park lived high on property taxes from petrochemical plants outside town; it was so flush that it had built a new campus for Forest Park High School in 1962, then built another six years later. Beaumont ISD was bigger, majority black, and struggled to raise money off a tax base drawn mostly from one shopping mall and Beaumont’s dying downtown. Price says the schools would have died without South Park’s largesse, but some black community leaders were wary of handing control of their schools to an all-white board.

South Park voters rejected the merger in 1983. So Beaumont ISD voters simply dissolved their district, leaving South Park to take over the schools.

The first election for the unified school board was a shocker: Black candidates won a four-to-three majority, in part because six white candidates ran to fill two at-large seats, splitting the vote. The black majority lasted only one term, but it stunned those who still believed integration was a passing fad. Kanelis says the reaction was intense. “There were elements in the white community that thought the earth had just spun off its axis,” he recalls. “There was discussion on the street that the African-American community was going to take over the school district, and they’re gonna wreck everything.”

The new school board made the most of its brief tenure, appending the names of local black community leaders to schools that had been named for Alamo heroes such as Crockett and Bowie. Superintendent Taylor returned the favor by closing an elementary school and converting it into his new district headquarters. “The thought was that he wanted the administration office in a better neighborhood,” Kanelis says, “to stick it in the ear of the black community.” Through the rest of the ’80s and into the ’90s, Beaumont’s school board was majority white.

Rev. Oveal Walker, pastor at Mount Calvary Baptist Church, says that back then, as now, the work for the black community was about self-defense. “Beaumont is a racial town. I’m not saying racist, but racial,” he says. “That’s been my experience over the past 30 years: that everybody has got to look out for their own race.”

the public during a school board meeting

in January 2011. (Valentino Mauricio/The Enterprise)

The court order on desegregation expired in the early ’90s, and new (mostly white) community groups formed to urge an end to crosstown busing; Walker says it was simply resegregation by another name. To keep from getting steamrolled by the board’s white majority, the three black trustees split vote after vote along racial lines. “We just fought and fought, our board members just kept forcing 4-3 votes until the superintendent requested that the TEA send some people down here,” Walker says. Two monitors from the Texas Education Agency spent three years with the district leaders, urging them to continue busing.

The 1994 election swung the school board to a black majority for the first time in a decade. This time it was no fluke, but rather the result of the white population’s consolidation on Beaumont’s west side and flight to outlying towns. After years during which each side accused the other of holding its interests hostage, the black community agreed in principle to neighborhood schools—essentially the same plan South Park had used to dodge desegregation for years—in exchange for better funding for schools in black neighborhoods. To lead the schools into a new era of cooperation, the new board settled on the charming young leader of Houston’s North Forest ISD, Carrol Thomas.

At first, Thomas didn’t want the job. According to Nolan Estes, one of the state monitors from Austin, who also helped lead the superintendent search, Thomas was happy in North Forest, proud of what he’d accomplished there. “There had been a lot of negative press coming out of Beaumont, so he didn’t want to jump out of the frying pan and into the fire,” Estes says.

Thomas had played defensive end at Texas A&I University in Kingsville—part of the A&M system today—and began his school career as a football coach and teacher in Lubbock. His leadership style relied heavily on the language of winning, of making no excuses, and his confidence quickly helped settle the rancor within Beaumont’s school community. He appeased white activists by implementing the shift away from school busing, but also promoted black administrators to top posts in the district and spread contracts to black-owned businesses. The share of black teachers in the district jumped 10 percent during his tenure. He created a small police force within the school district, staffed mostly with black officers, as a community-oriented alternative to Beaumont’s mostly white city cops. Thomas’ salary was $150,000, with a built-in raise of 3.9 percent for each year he received a good job review.

To make sure Beaumonters heard about the good news, Thomas hired a special assistant named Jessie Haynes, a former newspaper reporter who became Thomas’ district spokesperson and a close adviser. Thomas toured the country to deliver talks on school leadership. He was named president of the National Alliance of Black School Educators. He met President Obama; the photograph was widely reproduced around the district. The Texas Association of School Administrators named Thomas superintendent of the year and named Beaumont’s trustees the school board of the year. Banners appeared on Beaumont schools proclaiming it among the nation’s “Top 10 school districts” according to Business Review USA—a claim of dubious significance, the weekly Beaumont Examiner newspaper later reported, because it came from an online magazine hardly anyone had heard of. And when Thomas’ successor at North Forest was fired for poor money management a year after Thomas left, and the state took over the district, Thomas easily brushed off complaints that he’d been responsible. Instead, Thomas was named a finalist for the superintendent’s job in Dallas. The school board in Beaumont offered him a $100,000 bonus and a pay raise if he’d agree to stay; whatever magic Thomas was working, they wanted it to stay in Beaumont.

Thomas drew on all this goodwill in 2007 to pass a $389 million bond issue, one far more ambitious than he or the district had ever tackled. The money would cover new schools, repairs and a new stadium, all in one package that would cost Beaumonters an extra $100 or so in property taxes on a $100,000 house. The bond drew fresh attention from folks who hadn’t been watching the district before—new critics who worried Thomas had accumulated too much unchecked power and too much wealth to spread around.

Mike Getz is, in many ways, the face of the Carrol Thomas opposition. Late on a Thursday afternoon in September, he greets me at the door of his law practice in a quaint 52-year-old home a few blocks from Martin Luther King Boulevard. His bearing seems stern at first and it’s easy to picture him the way I first saw him, in school board meeting videos and news photos, flipping his lid like Mike Ditka on the sidelines after a blown call. But he smiles broadly as he talks about the schools today. Now that the state has taken over, he says, he’s “thrilled, exhilarated, elated. I can’t give you enough adjectives to describe the euphoria that I feel.”

Warm light fills the entry room through the big windows. A couple of years ago, during the height of tensions around the school district, someone threw a chunk of concrete through one of these panes. But the scorched-earth struggle he’s waged with the district, for which he’s been called a Klansman and a “red-eyed devil,” also launched his political career. Getz now has a seat on the Beaumont City Council, and in his front yard is a big red sign for his wife Allison Nathan Getz’s first political campaign, running as a Republican for tax assessor-collector.

Getz says he never expected to get so political. But as a lawyer, he felt like he could make a difference for a school district he saw making bad decisions. In the beginning all he wanted was a smaller, simpler bond issue. In op-ed columns, Getz warned that the big bond was simply irresponsible, but in the pressure cooker of live board meetings his language was more charged. The bond wouldn’t do anything to boost the performance of Beaumont’s schools, he warned, but it would certainly “make 100 black men rich.” So much money arriving at once, Getz feared, would become a slush fund for allies of Thomas and the board. “Through that bond issue,” Getz says today, “black citizens who never would have had the opportunity for the kind of wealth that they ended up with became wealthy.”

The district’s plans also included a project that some saw as a punishment for the white community: replacing the old South Park school, a three-story brick behemoth built in 1922 to accommodate the children of roughnecks who flooded in during Beaumont’s oil boom. The building had recently passed a structural inspection, and preservationists opposed its destruction. Getz sued to stop the teardown but lost. Demolition commenced on Good Friday 2010 with an excavator tearing into the old school, an image that graced the front page of the Enterprise the next day.

“The historic facade of the school, the beautiful architectural elements of it, that’s what they went after first,” Getz remembers. “And then they let it sit there for weeks without anything else. Like the old Romans used to do, you put the head on the spike, you put it on the bridge as a warning: ‘This is what happens to you if you mess with the Roman Empire.’ That’s exactly what they did there. Oh my god. How do you start a civil war?”

I return to Getz’s office the next morning to meet Donna Forgas, a retired accountant who’s run three times, unsuccessfully, for the Beaumont school board and has committed herself to finding fraud and waste in the recent school budget.

Forgas says the district’s financial records show misspent federal money—just half of a grant for homeless students went to the proper programs, she says—and generally irresponsible practices, including keeping all the district’s funds in one bank account. That, she says, probably helps explain why the district can no longer account for $70 million from the bond that had been earmarked for inflation. When the proposed $29 million stadium was finally finished for $45 million, with a million-dollar scoreboard that wasn’t in the original budget, it would have been easy to make up the difference with the inflation funds.

The contractors chosen to do the work, Forgas says, reflect a system that privileged support for black businesses over smart spending, and Getz agrees: He represented companies that sued the district claiming they lost out on construction contracts even though they bid lower than minority-owned businesses. Getz says some contractors were hired simply because they were black, with nothing to do but “stand around with clipboards.”

“From ’96 on, whites have been running to try to reclaim one of those districts. But by the grace and mercy of God as I see it, they were never able to.”

These are arguments that have been aired in Beaumont for years. At a 2010 board meeting days after the South Park demolition, Thomas pledged that the construction spending was legitimate. “There’s no judge, no court that can tell you what the truth and the facts are,” Thomas said. “I do believe the majority of the community realizes what the truth and the facts are.” Getz railed against Thomas from the microphone that night, calling him an “egomaniacal despot.” Then the school board voted to put Thomas’ name on the new stadium.

Getz says he was stuck; he didn’t see a way to hold the district accountable. “I became aware that as long as there were seven single-member districts, that nothing was going to change. Because people don’t go vote,” Getz says. “Most people live their life, all they want to do is raise their family, put food on the table and have a roof over their heads. They just don’t get involved in school board politics.” He says the board was stacked with people who enjoyed the power and prestige, and knew just how to keep it: “You can focus on just the very few people who vote for you, and make sure that they’re fat and happy, and you’re gonna be in office for life. And that’s what was happening.”

So Getz decided to change the equation. Since an order from Judge Parker in the mid-’80s, shortly after the school districts’ merger, Beaumont’s school board had been comprised of seven members from seven individual districts. Instead, Getz proposed returning to the old plan from decades before, with five districts and two citywide trustees elected at large. Getz says his plan wasn’t about race or ideology, just about cleaning up the schools, but the likely result would be a shift back to a white board majority. Voters approved Getz’s plan, but a group of Beaumont’s black ministers and community leaders sued, and the U.S. Justice Department scuttled the plan, saying it violated the Voting Rights Act. Some media reports likened the power struggle over Beaumont’s schools to plots for weakening minority voters’ influence such as Texas Republicans’ statewide redistricting plans and the state’s voter ID law. MSNBC branded the Beaumont effort a “right-wing plot.” Before any judge could decide, though, the U.S. Supreme Court issued its Shelby County v. Holder decision in June 2013, removing much of the Justice Department’s influence over voting rights cases like these.

Rev. Walker says the black community doesn’t have much recourse left to defend its majority. “From ’96 on, whites have been running to try to reclaim one of those districts. But by the grace and mercy of God as I see it, they were never able to,” he says. That figures to change after the next board election, which could come as soon as May 2015. At-large elections favor candidates with money to spend on a citywide election, and other than the 1984 election, Walker says Jefferson County hasn’t had a black majority on any elected body with at-large seats.

Getz believes Walker’s logic is a smokescreen, one used often to defend Thomas’ administration. “If anybody that was black tried to stand up to corruption and nepotism, they were ostracized and retaliated against. If you were white and tried to say something, you were painted as a racist,” Getz says. “And that’s almost as bad as being called a child molester, being called a racist, in the eyes of many in the white community.”

To Getz, suspicions about racism or a “right-wing plot” play off of outdated fears that a white administration today would neglect students of other races the way schools did in the past.

“I know there’s going to be some in Beaumont, especially in the African-American community, that will say, ‘Well, that wasn’t such a good time for us.’ You know, ‘We didn’t have the proper facilities, we were given short shrift, we did not have everything that the white kids had.’ And they’re right. And that was wrong,” Getz says. “Looking back through the prism of history, I can say, of course that’s wrong. But we’re not living in the past. And those people that have their feet stuck in the past can’t move forward. What I see is in the black community, there is a relatively small group of older, bitter individuals that just can’t turn loose of the wrongs they suffered when they were younger. … You’ve got to look forward and you can’t have a policy of retribution, which is kind of what the school district became most known for.”

For Beaumont NAACP director Paul Jones, there is no prism of history dividing the past from now. “It’s not the old racist process where you’ve got a water fountain here for whites and here for blacks. No, it’s never going to go back to that. It’s more sophisticated now,” Jones says.

Walker agrees there is a cycle to Beaumont’s race relations and no reason to think now is any different. “We had our wars and we came together, and then we had our wars again.”

In January 2012, just after the school board approved yet another 4 percent pay raise for its longtime superintendent, Thomas made the surprise announcement that he would retire that fall. By then, he had long been the state’s highest-paid superintendent, despite running a district of just 20,000 students; 16 years of annual salary bumps had driven his pay to nearly $350,000 a year. The district bid Thomas farewell with a retirement “extravaganza” in August at Ozen, the Pear Orchard high school renovated with the bond money Thomas oversaw. He sat onstage in a plush blue chair, grandchildren on his lap, as friends and co-workers shared memories. A Motown revue performance included a tribute to Thomas’ leadership. Outside, Getz and other detractors got into a shouting match with Thomas supporters; the conversation was wide-ranging and, though later accounts varied wildly, not strictly limited to the finer points of school management, but also included James Byrd Jr.—victim of the notorious 1998 hate crime in nearby Jasper—and Adolf Hitler.

By then, the scrutiny on Thomas’ administration had grown intense, and reporters and lawyers found that the trouble went well beyond over-budget stadiums with expensive scoreboards. Scandals piled up for Thomas’ successor, his longtime lieutenant Timothy Chargois, and the timing of Thomas’ exit began to look prescient. The Enterprise, local TV, and enthusiastic muckrakers like the Examiner and SETInvestigates.com feasted on the district’s downfall one scoop at a time.

The news reports were filled with fascinating, often embarrassing details. Jessie Haynes, the district’s spokeswoman, had given Beaumont’s high school graduates copies of her own book of advice to college students, full of frank admonitions against sexual assault, alcohol abuse and devil worship. “You had better at least think about your future cellmates,” the book reads. “They’ll be raping your booty when they hear you are in for rape.” The district’s transportation director was pulled over in a district-owned pickup truck—“drunker’n Cooter Brown … shithouse drunk, slamming curbs, [and] going into overshift,” according to the deputy who pulled him over—but was driven home by a district police officer. The Examiner revealed that Assistant Superintendent Patricia Lambert’s son received more than $350,000 for questionable printing services that had once simply been outsourced to Kinko’s. And Calvin Walker, a black electrical contractor who’d replaced the white-owned electric company the district had used for years, was indicted for overbilling the district $1.5 million. After a mistrial in Walker’s case, the school board voted against asking Walker to pay restitution. “Every week it was something new with Beaumont ISD,” Getz says, “and of course it drove sales. It almost became a bloodsport to bash the district.”

In November 2013, the FBI carried out a series of coordinated raids at the homes and workplaces of the district’s purchasing officer, Devin McCraney, and its comptroller, Sharika Allison, who eventually pleaded guilty to embezzling more than $4 million. From 2010 to 2013, the two had simply transferred money from the district to a fake company they’d created. The FBI is reportedly not finished investigating the district, and Getz, like many in town, is confident that the full scope of the corruption hasn’t yet come to light. “Walker, McCraney, Allison—this is just the tip,” he says. “They’re gonna find people, I believe, in the highest echelons of the former administration.” The Jefferson County district attorney and federal prosecutors have formed a joint task force to clean house in the district. Their most recent collar was West Brook football booster club president Bo Kelley, who is white, and who pleaded guilty in October to paying personal bills with money meant for the football team.

Players in the school district drama draw different conclusions about what all this wrongdoing says about Beaumont ISD. Critics like Getz have suggested an institutional rot—a culture of permissiveness that began under Thomas. The district’s defenders insist these were unrelated problems strung together by the white community in an illegal play to regain control of the city’s schools. But the intense media scrutiny, the web of score-settling litigation and the looming threat of state takeover did strange things to the people involved.

Getz was arrested at one school board meeting, pulled screaming from the room by the district police chief, for violating school board policy by naming employees during his statement. In August of last year, as Getz spoke to a crowd inside the district headquarters, Jessie Haynes approached and proclaimed the group unsafe for such a small hallway. She asked a school police officer to disperse the crowd, but the officer demurred. When someone told her to “shush,” Haynes began an a cappella rendition of “We Shall Overcome” until the hall had emptied. That moment might have become legend enough on its own but for an incident later that night. While the district’s lawyer held a press conference inside the district office, Haynes stood in a doorway to keep Getz, the school trustee Mike Neil and SETInvestigates.com reporter Jerry Jordan from getting in the room. Video of the incident shows Neil jostling the door open as Haynes presses to keep it shut, a quick altercation caught on video that took on a strange life of its own on the Internet. Following the incident, Haynes took months of paid “assault leave”—a designation usually reserved for teachers who’ve been attacked by students—until she filed a workers’ compensation claim instead, which was ultimately dropped. But shortly after the incident, Haynes was arrested and then convicted of “blocking a doorway,” prompting a “Justice for Jessie” movement among her defenders.

Incidents like that one, as well as the rancor within the school board and all the serious questions about the school district’s troubled finances, combined to make a state takeover seem increasingly inevitable. Earlier this year, as the state’s investigation into the district grew, so did the crowds of antagonists who showed up at school board meetings. When he appeared at meetings, Education Commissioner Michael Williams was greeted by a mostly white crowd in bow ties, Williams’ signature fashion accessory, and placards proclaiming their support for the T.E.A.—as in Texas Education Agency—Party. That gleeful crowd of interlopers from white-flight destinations such as Lumberton and Vidor, and their barely veiled tea-party references, did little to convince black community leaders that this was all about fiscal policy.

The state announced its takeover in April, though Commissioner Williams cited only McCraney and Allison’s embezzlement and Calvin Walker’s over-billing in his letter to Chargois, who resigned in June. The school board trustees, despite fighting to keep control, were all removed by TEA. Zenobia Bush, who rejoined the board in 2011 after two other stints dating back to the ’80s, says she was surprised. The state’s audit hadn’t found any criminal activity on the board’s part, and as she saw it, their job wasn’t to comb the district’s books for signs of embezzlement. “The other thing [Williams] told us was that he felt we had lost the trust of the community. And so, if that’s the case, then allow us to rebuild that trust,” Bush says. But as she sees it, Williams was hearing from only one sliver of the community—presumably Getz and the “T.E.A. Party” cheerleaders who wanted the board ousted. “Every time they tell me it’s not about a race thing, I tell them they’re lying. Because that’s exactly what it’s about,” Bush says. “It’s the fact that you don’t control this board that upsets you.”

To replace the board, and save the school budget from its gaping deficit, the state appointed a seven-member board made up of community leaders from around Beaumont—businessmen mostly—that will serve for up to two years before handing control back to elected trustees. This new board has four white members, three black. Williams chose Vernon Butler, who spent the last two years managing the state’s previous school takeover in El Paso, to serve as superintendent. Butler says his first job is to make up a budget shortfall of about $40 million, but the greater challenge is in the school community: “Unity, collaboration and trust,” Butler says.

Outside the city, the story of Beaumont’s troubled schools is probably best known by anti-spending activists who point to the budget excess and embezzlement as evidence that public schools already get far too much, that big school systems too easily invite bloat and greed. But to recover from this scandal, the district will have to draw on the great strength of public schools: that everyone has a stake in them, and that when the schools are great, everyone shares the pride. Even some of Thomas’ defenders are hopeful that, by handing control of the district to people who have never had a stake in it, the state takeover could bring some measure of unity to Beaumont at last. Like the formation of West Brook High School 30 years earlier, this takeover could be the new beginning Beaumont’s schools need.

Timeline: How Beaumont ISD came undone

On a wet September morning in downtown Beaumont, a handful of local TV reporters and news photographers are fanned out in front of the federal court building, waiting for a glimpse at two casualties of the federal investigation, the former finance officers McCraney and Allison, who will appear for their sentencing today. Minutes apart, they cross Willow Street flanked by lawyers and family, and as they breeze up the courthouse steps, the reporters pepper them with the usual greetings: “What do you want to say to the kids you stole money from?” “Any remorse?” “You look emotional. Are you upset today?”

They make separate, but similar, appearances in front of federal Judge Ron Clark. Allison wound up with a smaller cut of the money and kept a lower profile, mostly spending the money on her children’s health care and to pay back a series of payday loans (though she also loaned her boyfriend $50,000 for a new Escalade). But McCraney, who had been the district’s top financial officer, spent years “living like a rock star,” as one U.S. attorney put it, buying a new Ford F-150 and GMC Yukon, building onto his house and taking lavish vacations. For masterminding the embezzlement scheme, McCraney receives a longer prison sentence, and basically the only legal wrangling is over removing an extra penalty the law provides for having carried out a “sophisticated” scam. His lawyer argues that the district’s safeguards were so lax that no sophistication was required.

Judge Clark doesn’t buy it. And looking out from his bench at McCraney—a big man in a dark-gray suit and red patterned tie who is, indeed, looking emotional—Clark recalls that, years earlier, “I had the opportunity to be a guest at many African-American churches, and I was always struck by how many men weren’t there.” McCraney, first in his family to attend college, earning a good living at the school district, will spend the next five years and eight months in prison and many years after that paying 10 percent of his paycheck back to the state in restitution. “Given your history and background,” Clark says, “this case is particularly sad.”

Sitting in Price’s living room the next day, I ask him if the school district’s implosion wasn’t doubly damaging, because it came under Beaumont’s first school administration with such deep roots in the black community—could it just validate the old fears some white Beaumonters expressed about what could happen to the schools under a black administration?

Price agrees, except for the presumption that corruption was a new development. “Before Thomas got there, I hate to put it this way, but it was mostly a white environment,” he says. “So maybe they had ways of covering up, massaging over. It wasn’t until you mixed these two races—I’m gonna check on you, you’re gonna double-check on me.” That’s what it takes, Price says, to keep everybody honest in an arrangement like this. That suggests a perverse sort of upside to such deep-seated suspicion: When nobody trusts one another, it’s harder for anyone to cheat. But even if Beaumont is more aware, more involved today in how the schools are spending money, that misses the point of a unified public school district: to build trust and understanding between different sides of the community. On that count, Price isn’t encouraged.

“Booker T. Washington said, in some things we can be as separate as the five fingers, but there’s certain situations that you want to play on a keyboard, you want to have blacks and whites working together to create your tune. And I wouldn’t be surprised if we’re gonna find ourselves more divisive because of what’s coming out,” he says. “People have told me, ‘Richard, they did it to us when they were in control.’ And my response: Don’t do to them in the manner that they did to us. We must be better.”

Even some of Thomas’ defenders are hopeful that … the state takeover could bring some measure of unity to Beaumont at last.

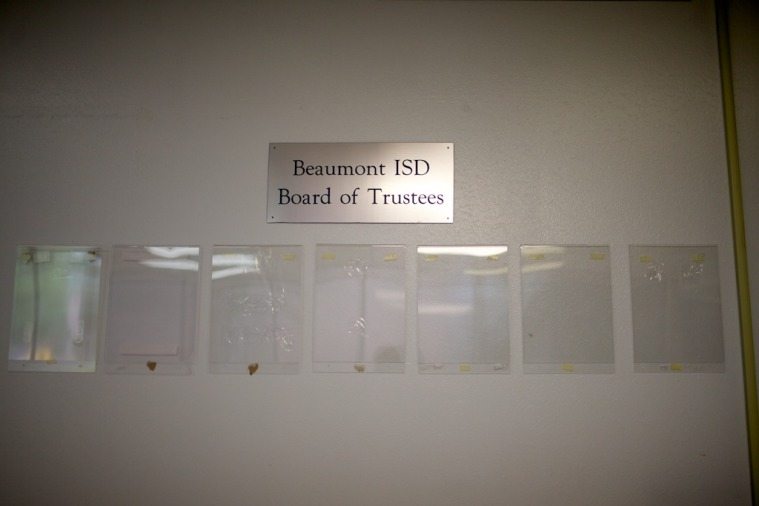

In the entryway to the district headquarters, there are signs of change and reminders of the old days. Seven empty frames hang below the words “Beaumont ISD Board of Trustees.” Above them on the wall are three state awards for fiscal responsibility during the Carrol Thomas era.

In the boardroom, Vernon Butler sits silently beside the managers as they hear budget reports and approve contracts. The votes are all 7-0. The room is packed, the crowd mostly black, and most people are there to support the school district police department, which the district may cut. Butler has said replacing the officers with city police on contract would save the district money. Parents, officers and even the district police chief take turns at the microphone to defend the department. Its officers work full time in the schools, they say, and understand students better than city police, who often don’t even live in Beaumont. “We don’t want another Mike Brown, we don’t want to be another Trayvon,” one speaker said, pleading on behalf of the district police. “If you don’t want another Ferguson in Beaumont, don’t do it!” (The next day, Forgas tells me that was clearly a threat.) Still, there’s a sense of inevitability in the crowd. “That’s what they do. The fix was in,” a man mutters behind me.

But later that night, the board holds off on dissolving the department, opting only to fire the district’s police chief. The “good cause” for his termination went unspecified, but the effect is immediate: another reminder of the Thomas years is gone.