Beto Bets on the Border

Will showing up with a high-minded call for border solidarity translate to the historic levels of Latino turnout that O’Rourke needs?

–

by Justin Miller

August 24, 2018

After winning the Democratic primary for Beto O’Rourke’s congressional seat, his friend and political ally Veronica Escobar, an exuberant former El Paso County judge, began planning a four-day “Border Surge” bus tour to spread the gospel of Beto in the Texas borderlands, where he struggled in the primary.

The goal of the tour, which wrapped up this week, was to knock on thousands of doors and kick off a fevered get-out-the-vote push that will increase Democratic voter turnout in the 32 border counties by 15 percent. That lofty feat would bring in 170,000 new votes and, Escobar hopes, help put O’Rourke over the top in November.

In order to come even close to winning, O’Rourke needs to do a hundred different things that Democrats have failed to do in the past. That includes achieving record levels of turnout in the Rio Grande Valley, one of the largest- and fastest-growing pockets of Latino voters in the nation — and an area notorious for low voter participation.

After years of Republicans (and some Democrats) using the U.S.-Mexico border as a punching bag for their war on immigration, O’Rourke and his allies are hoping that a high-minded call for border community solidarity from El Paso to Brownsville — 825 miles to the southeast — will resonate with voters.

With less than two months until early voting begins, O’Rourke’s most recent campaign swing came with a sense of urgency.

The Observer tagged along with Escobar’s “Border Surge” bus tour, which included rallies and blockwalking in Laredo, McAllen and Brownsville, to see what O’Rourke and his allies are doing to reach out to Latino voters and jumpstart turnout in one of the most crucial regions for statewide campaigns.

‘He’s the male Ann Richards’

Just weeks after launching his presidential bid by calling Mexicans “rapists,” Donald Trump flew to Laredo to preach about the dangers of illegal immigration and promote his border wall plan. Surrounded by a security detail, Trump claimed that he came to the Texas border city at great risk to his personal safety.

Three years later, Escobar and a busful of about 30 volunteers — mostly older women, all without a single bodyguard — survived the harrowing 10-hour journey from El Paso to Laredo for the first stop in her “Border Surge” tour.

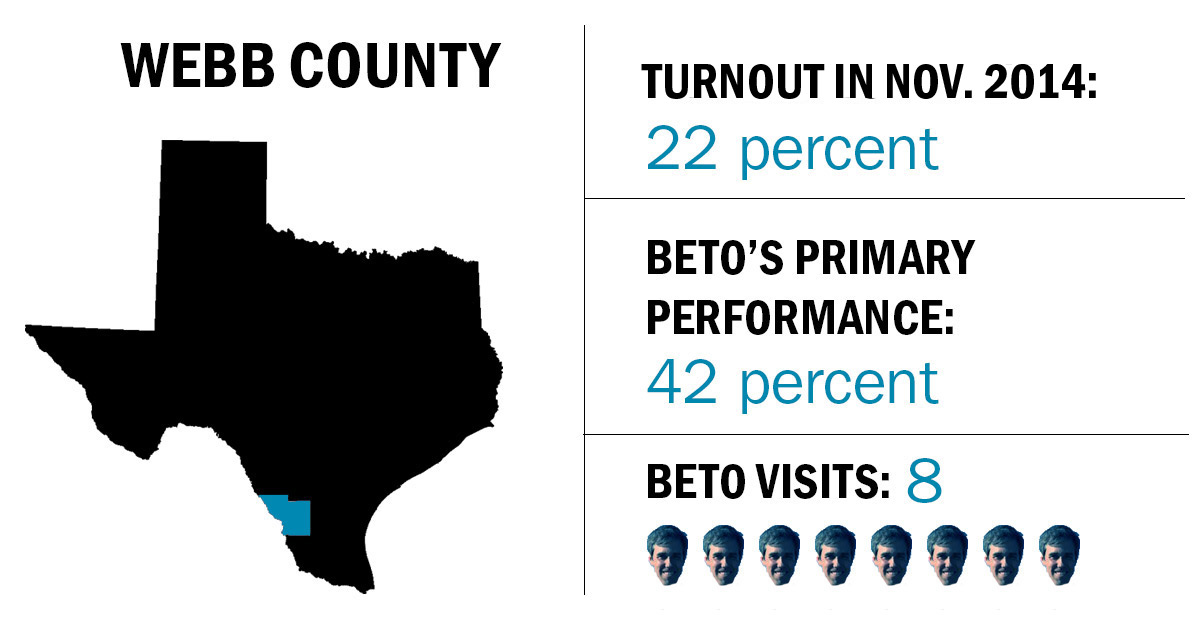

With the 100-degree heat lingering into the evening, hundreds of Laredoans flock into the Casablanca Ballroom to hear from O’Rourke as he makes his eighth trip through the city. “He’s the male Ann Richards as far as charisma goes. And the South Texans loved Ann Richards,” former Webb County Judge Mercurio Martinez tells me. “He wins over every person he talks to.”

The statewide Democratic ticket has tagged along for O’Rourke’s swing through Laredo, McAllen and Brownsville. They deliver a series of long-winded stump speeches like an amateur warm-up act killing time before the headliner, who’s speeding down I-35 from an afternoon event in San Antonio.

You can feel the crowd turn electric when O’Rourke and his entourage enter the hall. He hangs off to the side, greeting supporters and taking photos as Cristela Alonzo, a comedian and TV star from Hidalgo County and Beto’s travel companion through the Valley, warms up the crowd.

Then he jumps on stage and delivers a speech in his hallmark style — stream-of-consciousness, but remarkably coherent. He touches on everything from family separations, Dreamers and health care to veterans and ending ongoing wars to Trump’s “collusion in action in Helsinki with Vladimir Putin.” He’s often at his most candid when talking about growing up in El Paso and about the tragedy of family separations.

As a native El Pasoan and close friend of O’Rourke’s for about 20 years, this campaign is personal for Escobar. “I feel that we are giving [the state] our best. He is a son of the border,” she says. But she worries about the prospect of O’Rourke losing because of dismal border turnout. Political analysts point to early indications that, even in the Trump era, Latino turnout is likely to dramatically fall off like it has in previous midterm cycles. And in a cycle that’s focused on flipping suburbs, many Democratic groups have, once again, failed to prioritize Latino outreach. “Shame on us if that were to happen,” she says. “That would send a really terrible message to the White House, to state leaders, to Republicans, to all those who demonize us that we’re OK with it and that it doesn’t bother us.”

‘This election could be decided by the person whose door you knock on’

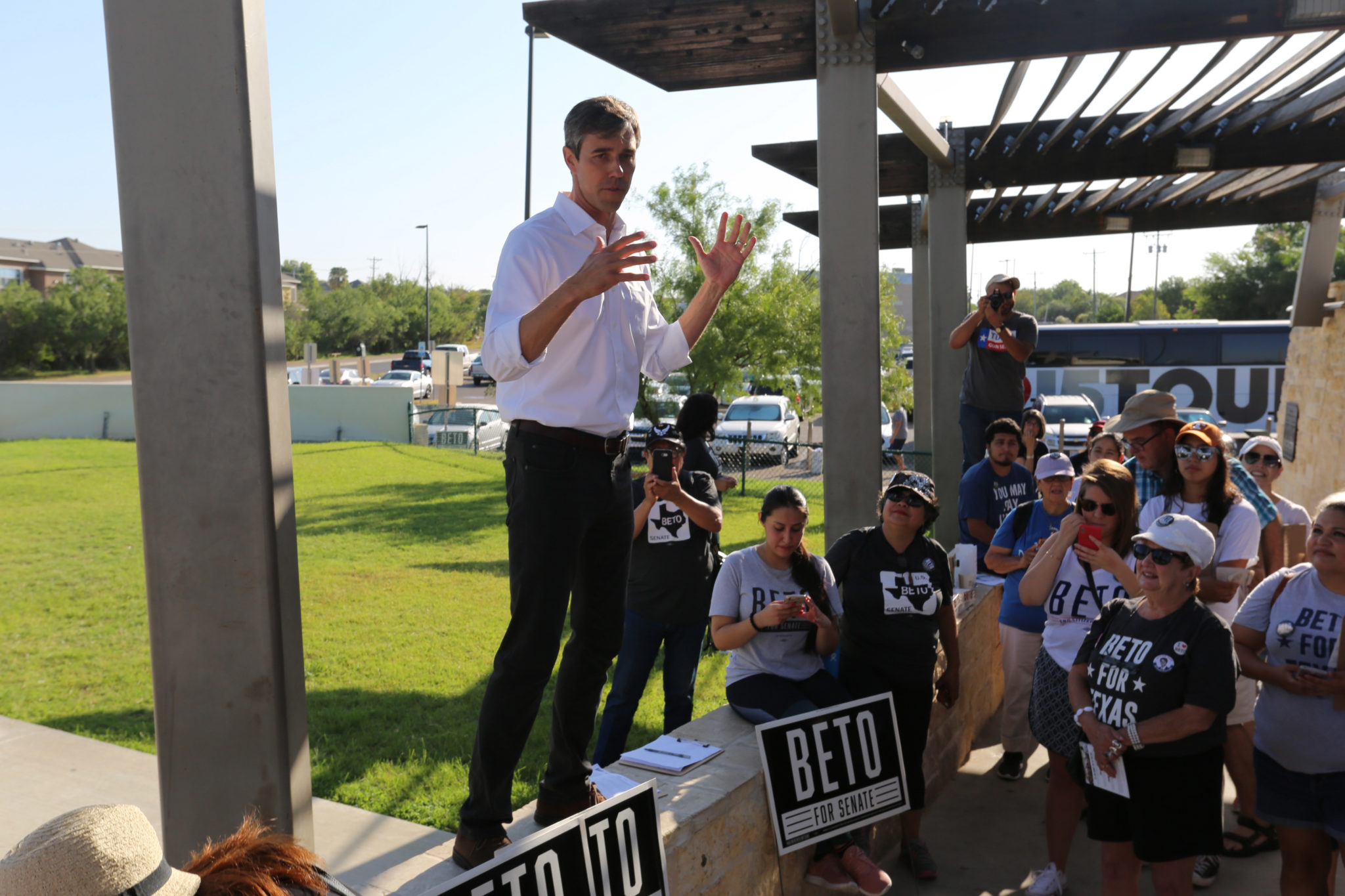

On a steamy Saturday morning, O’Rourke climbs onto a stone ledge at a park in north Laredo to present to a crowd of about 60 volunteers his romantic belief in the power of blockwalking. “They may not see the TV ads that we’ve got running now, they may not hear the radio spot that might play on their way home from work. They will remember that you took the time this morning … to listen to them.”

Even as his campaign starts to ramp up more traditional modes of outreach, he has no intention of de-emphasizing this cornerstone of his DIY campaign. “In the closest Texas Senate election in decades … this election could be decided by the person whose door you knock on.”

Using Polis, the campaign’s voter database app, which provides a real-time map of low-frequency Democratic voters, Escobar goes from house to house in Laredo’s middle-class Hillside neighborhood. It takes a minute to get her bearings, briefly walking the wrong way as she tried to find a street. “This is the problem with door-knocking in a city you don’t know,” she says. Another problem: It’s hard to convince unlikely voters to vote when they don’t answer the door. For the 45 minutes I tagged along, she knocked on about a dozen doors and got answers at only one or two. She’d leave a handwritten note, hoping that might help.

Tagging along with Escobar is Sergio Mora, a former Webb County Democratic Party chair. The enthusiastic crowd at last night’s event makes him think change just might be afoot in Laredo. But is there any other evidence that voters are unusually fired up. He shrugs. “That’s the big experiment this cycle.”

One El Paso volunteer tells me that most people who answered their doors in Laredo had never heard of O’Rourke and many had no intention of voting.

‘This is a powerfully sacred place to me’

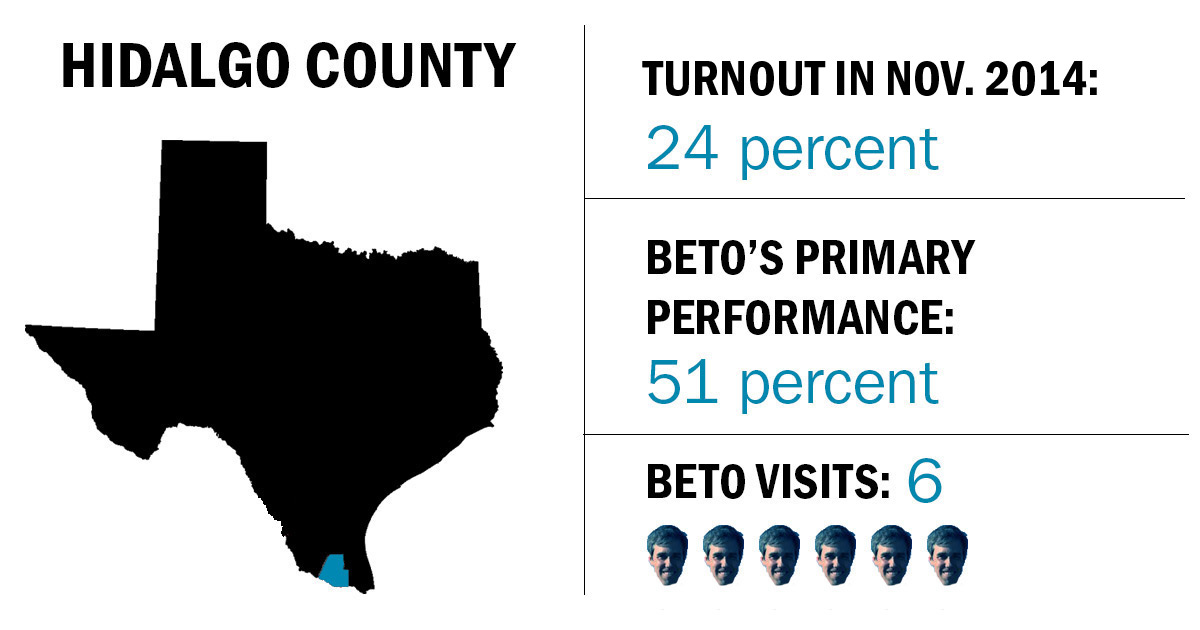

The 150-mile stretch of remote highway between Laredo and McAllen has lots of big ranches, wind turbines and Border Patrol agents, but not much in the way of voters. The “Border Surge” bus skips past Zapata, Jim Hogg and Starr Counties, roaring on to Brownsville. Meanwhile, O’Rourke stops off for his sixth visit to McAllen, the seat of Hidalgo County. It’s the epicenter of the Valley, where the number of registered voters has more than doubled since 2000 to about 330,000.

Several hundred supporters packed Cine El Rey, a downtown theater, to capacity with even more folks filing into the restaurant next door to watch him via livestream. O’Rourke tells reporters before his speech that the Valley often feels like the center of the universe to him. “This is a powerfully sacred place to me.”

While he’s cast himself as an unsullied ally of the border, O’Rourke’s voting record includes a wrinkle or two. Pressed by a local reporter on whether his controversial vote for an appropriations bill that put at risk the future of the local Bentsen-Rio Grande Valley State Park, he performed an uncharacteristic punt. He says he’s “working with colleagues on both sides of the aisle. We’re doing everything we can to stop that [from being constructed].”

With that, O’Rourke was whisked away by his aides.

‘People always call Brownsville and the Valley ‘the sleeping giant”

The hour-long drive through the suburban sprawl of chain restaurants and shopping centers between McAllen and Brownsville is a reminder of the Valley’s rapid growth — even as climate change and urbanization put the Rio Grande at risk.

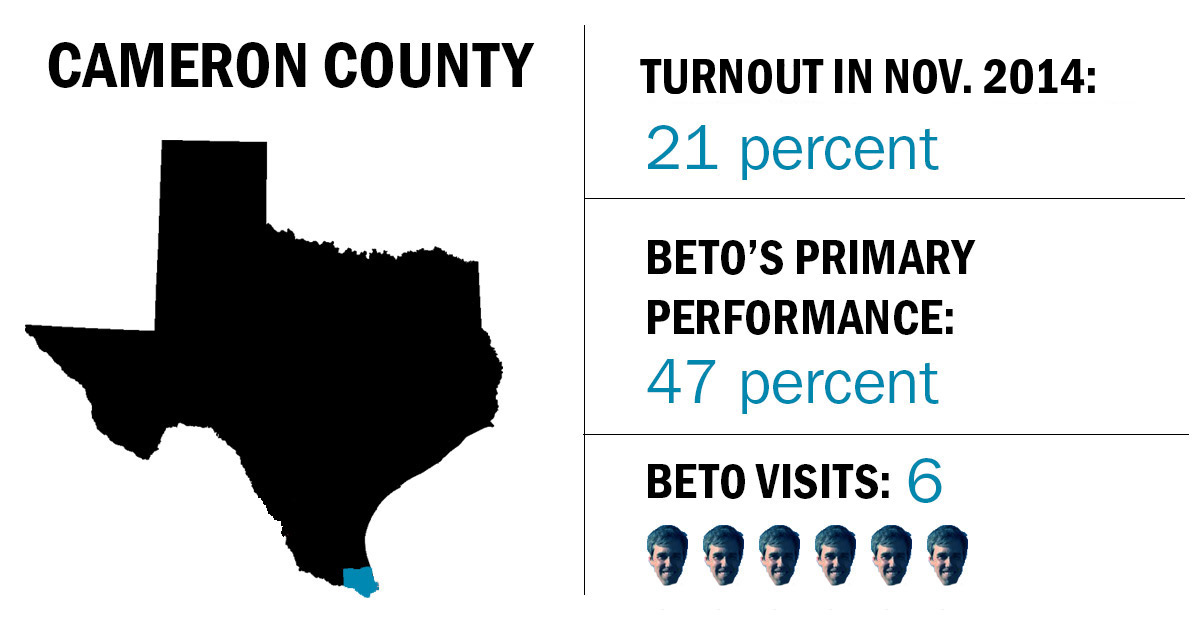

On the border by the Gulf, Brownsville is the heart of Cameron County. O’Rourke very nearly lost here to Sema Hernandez, an unknown Houston activist, and now needs the area to turn out for him in huge numbers. This is his sixth visit to Brownsville.

At his third and final event during his Valley swing, hundreds pile into the sweaty Tex-Mex Nightclub on a frontage road off Interstate 69 to hear O’Rourke deliver another barn-burner. Afterwards, as he wends his way through the crowd to get outside, greeting well-wishers and selfie-seekers, he emphasizes the importance of the RGV to his statewide strategy. “It’s everything. It’s everything,” ticking off how many times he’s been to Laredo, McAllen, Brownsville and other Valley towns.

O’Rourke’s rallies often feel like an alternate universe. People are filled with hope, their Texas cynicism washed away. It’s a place where anything — a post-partisan reckoning, a surge in Valley turnout and yes, even a Democrat winning statewide — seems possible. Life is sweet at a Beto rally. But outside that bubble, the feeling can get quickly wiped away.

The Valley’s elections are driven by an internecine political machine with a long history of corruption. Candidates lean heavily on politiqueras, who charge campaigns to turn out voters. His campaign has prided itself on doing things differently, and in the primary O’Rourke apparently declined to use them.

I asked whether he has any plans to use politiqueras for the general election. “We’re getting behind those who are volunteering their time to knock on doors. There are some neighborhoods where the residents there don’t have the luxury to knock on doors on a Saturday. They’re working their second job or their third job,” he says. “If we can find paid staff in those neighborhoods who are gonna be able to knock on doors, who know their neighbors, we’ll do that as well.”

Vicente Martinez, a local activist and recent graduate of the University of Texas-Rio Grande Valley, is skeptical of a voting surge around here. “People always call Brownsville and the Valley ‘the sleeping giant’” and wonder if now is when it will wake up, he says. “I heard that in elementary school and I heard that after Trump was elected.”

Is Beto doing enough to reach young people? Martinez smiles and points to the venue where the band is still playing. “Tex-Mex conjunto. That’s not a millennial thing. … It’s a little stereotypical.”

‘The greatest candidate of our generation’

A powerful Gulf breeze sweeps through Tony Gonzalez Park, cutting the early morning’s humid heat and rustling the palm trees that dot the park. Volunteers sip on coffee and munch on pan dulce as they get ready to hit the streets of Brownsville. Escobar grabs a bullhorn and introduces O’Rourke as “the greatest candidate of our generation.”

This is Day 22 of his relentless 34-day sprint around the state. Dressed in his black skinny jeans and white dress shirt, which he’ll wash during a live-streamed laundromat trip a few hours later, O’Rourke delivers an energetic call to action. But the fatigue is evident in the bags forming under his eyes.

After his speech, he heads out to block walk in the surrounding Southmost neighborhood with State Representative Eddie Lucio III, a 39-year-old attorney whose father, Eddie Lucio Jr., serves in the Texas Senate. From there, he stops for a roundtable in Harlingen, eats a Tex-Mex lunch, does his laundry and drives the two hours north to Alice for a town hall.

Tony Martinez, the Brownsville mayor, says O’Rourke just might have the winning political formula, but admitted that “he’s probably not as known [in Brownsville] as I’d like him to be.” To increase turnout by 15 percent in this county, O’Rourke needs to drive out 25,000 more voters than Democrats did in 2014.

Cameron County Judge Eddie Treviño Jr. is one of the few not wearing a Beto T-shirt — he’s facing an election fight in November and sports his own black-and-orange campaign shirt. He says that O’Rourke has injected a sense of urgency into the local politics and is doing the work that Democrats in the area have long neglected to do.

O’Rourke’s multiple trips through the Valley seem to be moving the needle, Treviño says, at least a little bit. “I think we’re going to surprise a lot of people. I like that we’re just creeping up now and not gonna peak too early,” Treviño says.

Blockwalking as a duo in Los Fresnos, a small exurban town 30 minutes north of Brownsville, Treviño and Cameron County Clerk Sylvia Garza-Perez emphasize to residents that Beto is a Democrat and a fronteriza who is against family separations.

Of those who answer their door, almost no one knows who O’Rourke is, but they politely listen, nod along and promise to vote.

Hanging out in his yard with his boxer, Luis Gonzalez was the only person who knew of O’Rourke, having voted for him in the primary. He’s not so sure about any sort of surge and lamented the fact that O’Rourke seemed to focus on the bigger Valley hubs like Brownsville and McAllen. “What about the farm towns? Why isn’t Beto coming here?” he asks.

‘I don’t believe it will happen organically’

At their last blockwalking event on a Monday morning, Escobar and her El Paso volunteers gathered at a park in a nice suburban neighborhood on the northside of McAllen, waiting for local volunteers to show up. Luciano Chano Garza, a local party activist, begins calling up more people to see if they could come out. Celia Hilber, an older woman who recently moved back to the Rio Grande Valley from Alabama, was one of the only other local volunteers there. “I may not be able to give much money, but I can give my time and effort,” she says after taking a team of El Pasoans to blockwalk.

Danny Diaz started Cambio Texas with the sole purpose of increasing turnout in the lower Valley. The group hopes to target about 25 precincts in Hidalgo County — where about a third of the population lives in unincorporated colonias — with especially bad turnout in 2014. But the group is still fledgling and doesn’t have much in the way of money to fund a large-scale operation. He’s talked to the state Democratic Party, but says they haven’t committed any sort of funding.

That leaves O’Rourke’s campaign trying to fill in the gaps. He’s been running radio ads in the area for a while, opened up two campaign headquarters in the Valley and hired a cadre of local field organizers. But the campaign is still largely relying on volunteers to help with phone-banking and door-knocking.

“I don’t believe it’s a guarantee that [a border turnout surge] will happen. I don’t believe it will happen organically. I don’t believe that anger alone will fuel it. But we have one of the two components: an inspiring candidate,” Escobar says. “We need an army of field volunteers knocking on doors and spending the time with those voters who [would otherwise] stay home.”

Infographic sources: 2014 figures from the Texas Secretary of State, 2018 figures courtesy the Texas Tribune.