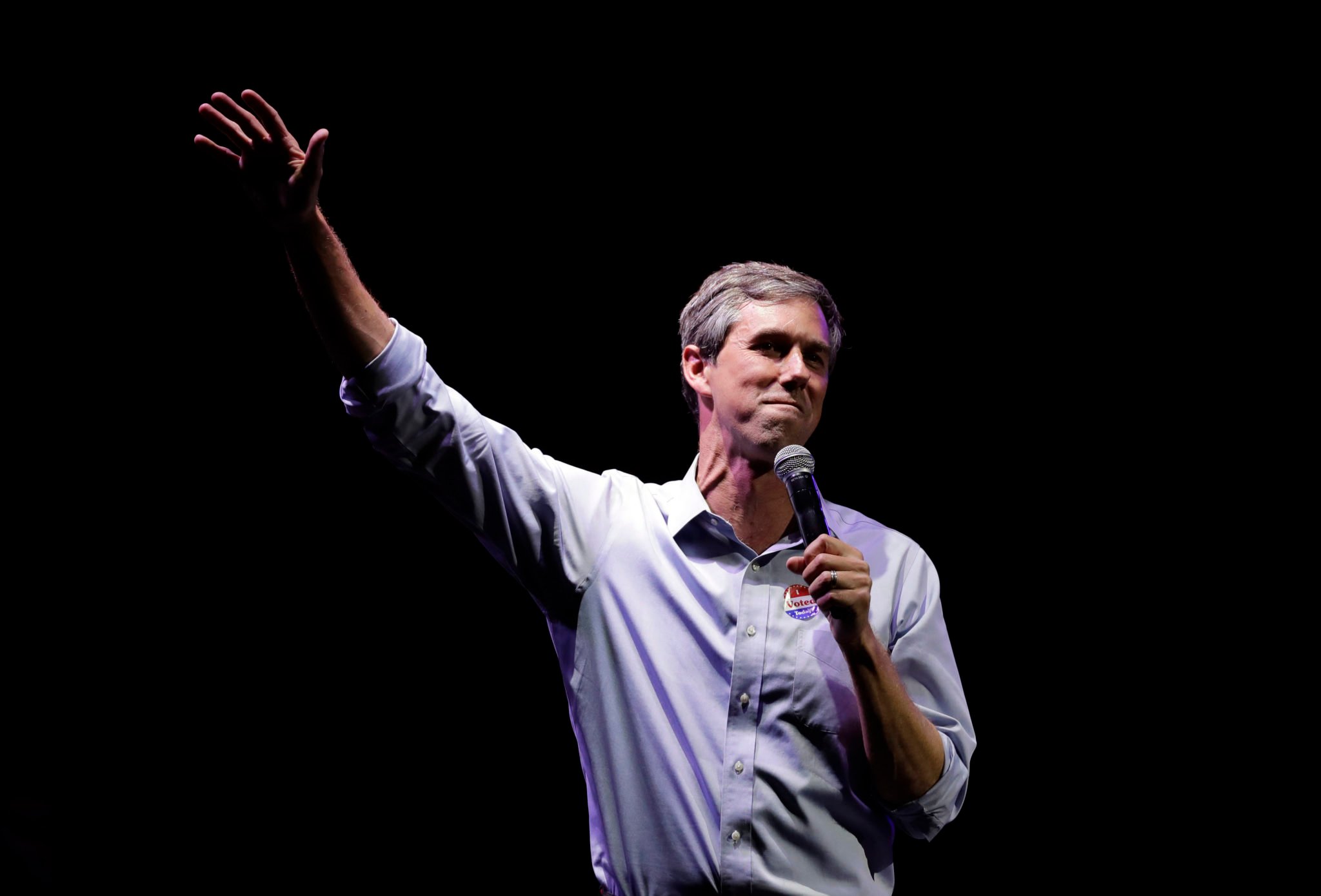

He May Not Be a Candidate, but Beto O’Rourke is Rebuilding His Texas Organizing Machine for 2020

O’Rourke’s 2018 Senate campaign was fueled by an organizing network of 20,000 volunteers. Can he harness that energy again without being on the ticket?

Beto O’Rourke began 2019 as a political phenom, but ended it as an also-ran. The much-hyped former U.S. representative from El Paso initially rode a wave of optimism from his nationally watched Senate campaign, but struggled to gain support in the presidential race. It was an underwhelming end of a chapter for a man who was once viewed as the great hope for Texas Democrats.

But even though—to the dismay of many supporters—O’Rourke opted not to jump into the crowded Democratic primary to take on Senator John Cornyn, he had no intention of watching 2020 from the sidelines.

His 2018 race against Ted Cruz, and the down-ballot Democratic wave that came with it, signaled that Texas is now a bona fide battleground in 2020. Democrats could potentially take control of the state House for the first time in two decades. A battery of state and national Democratic organizations is now committed to spending big money on Texas legislative and congressional races. And the eventual Democratic presidential nominee might actually make a real play for the state’s 38 electoral college votes.

So what’s O’Rourke’s role in this? He saw an opportunity in the 20,000 volunteers in Texas who provided the organizing jet fuel for his Senate campaign. That statewide political operation was unparalleled in Texas, and even the nation. It was O’Rourke’s magnetic charisma and aspirational call for a new kind of politics that attracted masses of volunteers in the first place, and only he could get that going again. But this time, he won’t be a candidate.

Like his 2018 campaign, O’Rourke’s new venture is centered on a romantic belief in the power of door-knocking and personal interactions.

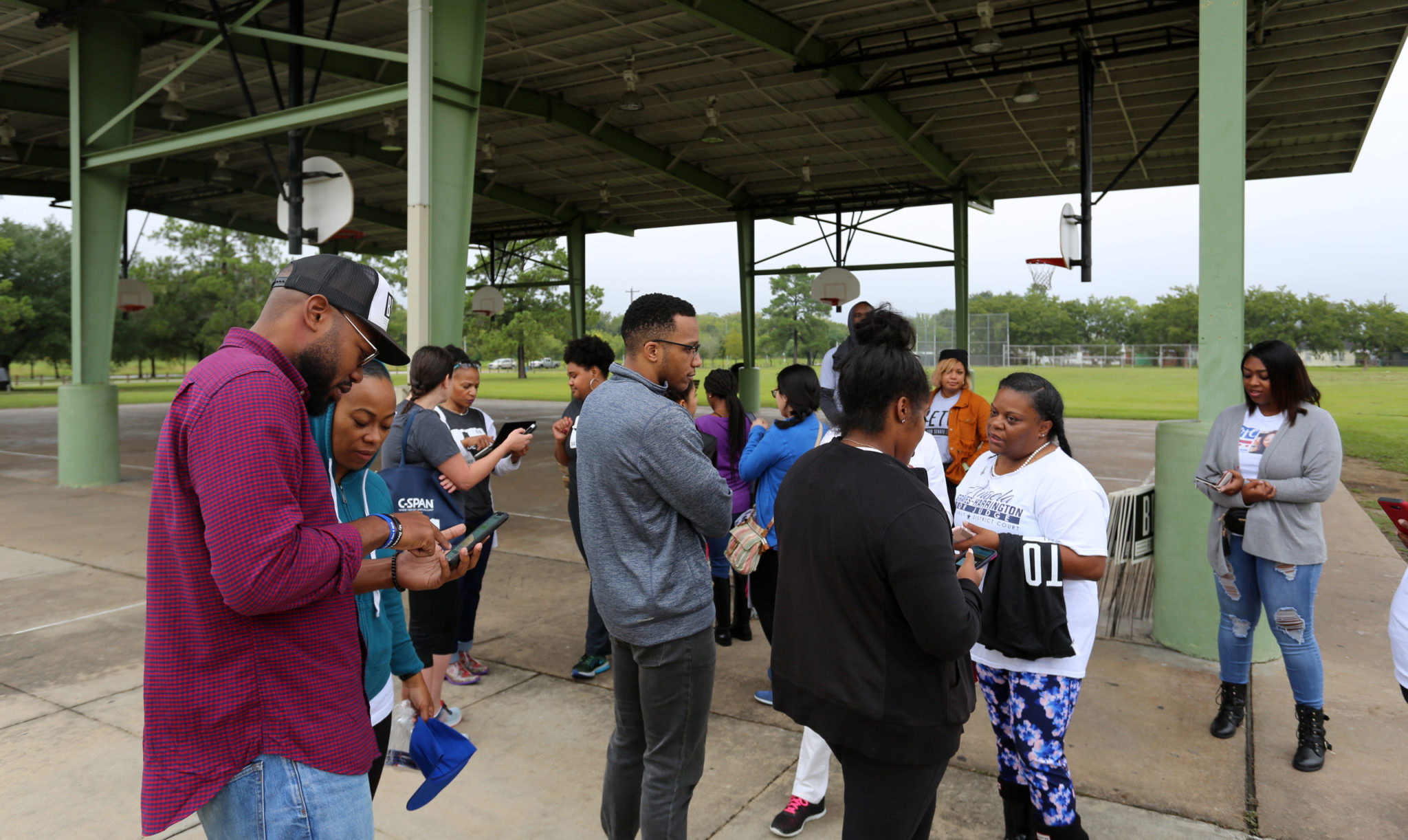

In late December, O’Rourke launched a new venture called Powered by People that aims to reignite his organizing network, calling on volunteers to put their energy into block-walking and phone-banking for Democratic candidates in key districts and statewide campaigns to defeat Cornyn and Donald Trump. O’Rourke believes that Powered by People can be a powerful force in what is already a crowded 2020 landscape in Texas.

“I just don’t know that there’s any other statewide organization that is so singularly focused on raising, organizing, and mobilizing volunteers as we are,” O’Rourke told the Observer. “I felt like we had something that was very unique to bring to this and a very unique vision for how we can be helpful to Texas.”

Flipping state House and congressional seats in the suburbs—where many of the Democratic targets are located—is squarely in O’Rourke’s wheelhouse. He made huge inroads there in 2018, helping convert a dozen House seats. Now, Democrats need to pick up just nine more to take control of the House. That happens to be the exact number of House districts still held by Republicans despite O’Rourke having beaten Cruz there. In several more, he was well within range. The Democratic path to winning the Texas House, it seems, was paved by O’Rourke. “Not only can we do this; in a way, we have done this before,” he says.

With Powered by People, O’Rourke’s first priority is the special election for House District 28 in suburban Fort Bend County. On January 28, Democrat Eliz Markowitz will face Republican Gary Gates in a runoff for the seat, which has long been a GOP stronghold. While the race is on the Democratic radar, it wasn’t near the top of the list: Trump easily won the district in 2016, and incumbent John Zerwas was reelected in 2018 by 9 percentage points. But O’Rourke came within just 3 percentage points of Cruz in the district, and when Zerwas unexpectedly retired, Democrats saw an opportunity. Support flooded in from all directions.

The special election is a weathervane for the Texas suburbs. If Markowitz can pull off an upset or even come close, that will set off alarm bells for Republicans and bolster Democrats’ electoral prospects.

To help assemble an organizing infrastructure for volunteers in the district, O’Rourke turned to Fort Bend County resident Katherine Stovring, a super-volunteer on his 2018 campaign. She not only knocked on an estimated 10,000 doors, but built up a volunteer army in Fort Bend suburbs like Katy, Fulshear, and Sugar Land. “Without a ton of supervision or guidance, she developed her own network and methodology and has been incredibly effective at reaching voters,” O’Rourke says.

Trump’s election motivated Stovring to get more involved in politics, and O’Rourke’s campaign became a vehicle. She focused almost all of her time in the suburban Houston House District 132, canvassing for O’Rourke and Dems all down the ballot. State House candidate Gina Calanni ended up ousting the Republican incumbent by just 113 votes. “I have never felt more powerful in my life,” Stovring told the Observer.

This empowerment of volunteers was central to O’Rourke’s 2018 campaign. It was harnessed through a strategy called distributed organizing, which elevates volunteers from menial task-rabbits for campaign staff to active parts of the operation with significant responsibilities. Bernie Sanders’ 2016 presidential campaign pioneered the model, and when O’Rourke was convinced to employ it in in 2018, he hired Bernie campaign alum Zack Malitz to run his Senate field organizing program.

It grew into one of the most formidable campaign machines in modern politics. Hundreds of volunteers across the state turned their homes into pop-up campaign offices, committed to training volunteers, and led local canvassing efforts. By the end of the campaign, O’Rourke’s volunteers had knocked on 2.8 million doors, sent more than 10 million texts, and made 20 million phone calls. In its final push ahead of Election Day, the campaign was hitting 340 doors a minute.

“Beto is one of the best organizers this state has seen in recent memory,” Malitz told the Observer. “He was relentless in building a volunteer organizing operation that gave volunteers real responsibility.” The result was what Malitz says was likely the largest voter-outreach operation in the state’s history: “The possibility that he’ll rebuild his organizing machine is potentially game-changing in 2020.”

Despite O’Rourke being the ostensible figurehead of Powered by People, he is not in charge in House District 28. That role is filled by Stovring, who is deeply connected in the area and knows how to quickly assemble a volunteer operation.

Since launching the group, O’Rourke has made Fort Bend County a second home. And though he’s no longer a candidate, it’s clear that the energy within his volunteer network has not gone dormant. ”It’s the Beto effect,” Stovring says. “If you look at core team organizing at the local level, all of us are people who Beto got off the couch in 2018. Now we’re more experienced and we know what we’re doing.”

In the two weekends leading up to early voting in Fort Bend this past week, Powered by People mobilized 900 people for block-walking shifts and knocked on about 24,000 doors. The early voting period saw a huge uptick in turnout compared with the special election’s initial open primary back in November.

Of course, O’Rourke’s Powered by People is far from the only player in town. State and national Democratic organizations—including the Texas House Democratic Campaign Committee, the Democratic Legislative Campaign Committee, and the National Democratic Redistricting Committee—have pumped in more than $1 million to help Markowitz, including last-minute injections for TV ad buys.

“The possibility that he’ll rebuild his organizing machine is potentially game-changing in 2020.”

O’Rourke stresses that his group is committed to working in tandem with those organizations. He’s had conversations with state Representative Celia Israel, who is coordinating the House Democrats’ campaign efforts, and other grassroots groups like Flip the Texas House, for which he has already helped raise money.

In HD-28, O’Rourke has raised about $20,000 for Markowitz through email blasts and social media posts. But fundraising is not where he sees himself making the biggest difference. Like his 2018 campaign, O’Rourke’s new venture is centered on a romantic belief in the power of door-knocking and personal interactions. For him, one volunteer like Stovring is more valuable than a $500,000 ad buy. “So finding the Katherine Stovrings of Texas and really making sure that the power is in their hands … is critical,” he says, to scaling up an operation similar to 2018.

What distinguished O’Rourke’s Senate campaign was his resistance to the traditional tactics of polls, talking points, TV ads, and glossy mailers. It was his struggle to maintain that outsider vibe while also succumbing to the norms of a national campaign that made his short-lived presidential bid feel discordant.

But he’s as committed as ever to the sort of DIY approach that can make political engagement much more personal. Beyond the electoral goals of his new project, he hopes to continue to reorient the way that Texas politics is done.

“I really hope that this is at least in part the antidote to the cynicism that you have in politics right now … the kind of corporate automated politics that is sort of a turnoff to so many people,” he says. “In a very digital automated age, this manual labor and human effort, I think that’s the thing.”

READ MORE:

-

A Solitary Condition: Texas has banished hundreds of prisoners to more than a decade of solitary confinement, an extreme form of a controversial punishment likened to torture. Many of these prisoners aren’t sure how—or, in some cases, if—they will ever get out.

-

17 Great Books on the Border to Read Instead of ‘American Dirt’: There’s no shortage of talented Latinx writers with all kinds of stories to tell. Let’s make space for them.

-

In Texas, Thousands of Kids Lose Medicaid Coverage Each Month: Texas has the most uninsured kids in the nation. But state lawmakers have made it especially difficult for kids to stay on Medicaid.