Unearthing a Lost World

A version of this story ran in the August 2015 issue.

Big Dig

In Baylor County, paleontologists are assembling clues to the prehistoric world of Dimetrodon.

By Asher Elbein

August 25, 2015

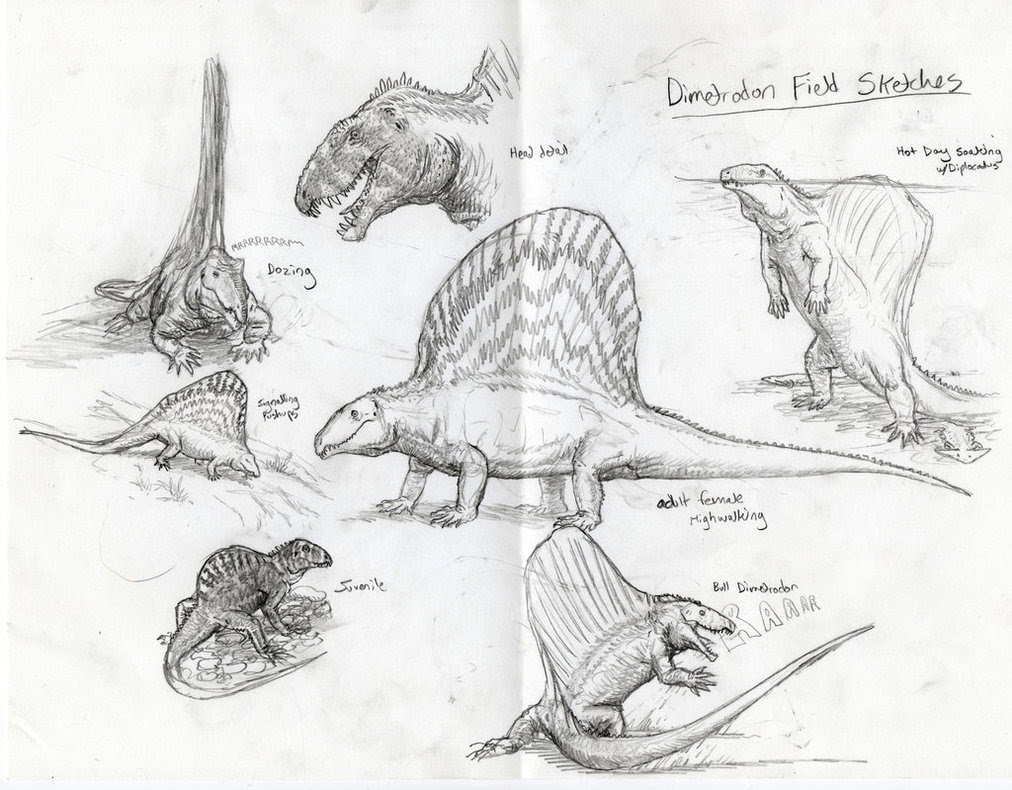

At first it had no name. The beast was a mammal relative with a heavy skull, a mouth full of fangs, and a tall dorsal sail made of skin stretched over long struts of bone. Sinuous as a crocodile, leathery scales shining in the hot sun, it padded along black-mud swamps and highlands shaded by swaying tree ferns. Sixty million years before the first dinosaur, it slept, basked, chased and killed. It breathed. It was alive.

It’s June 7, 2015, and one of its vertebrae lies cool and heavy in my hand. I’m crouched on the edge of a small quarry next to a band of volunteers and paleontologists with the Houston Museum of Natural Science. The site, a flat hollow scooped out of the red hillside, is one of the five fossil digs dotting the Craddock Brothers Ranch, a 4,950-acre expanse of scrubland just outside of Seymour, the seat of Baylor County, between Abilene and Wichita Falls. White fossil jackets—blocks of plaster-encased rock containing cargoes of bone—surround us, casting long shadows over the scatter of screwdrivers and brushes in the dirt. The tools are forgotten. A moment ago, David Temple, associate curator of paleontology with the museum, pulled a section of blue tarp away from an eroding bank and found the miniature canyons between plaster-covered rocks scattered with bits of gray bone.

“We’re going to have to mark this before we dig any of it out,” Temple says. He looks at the volunteers. “Can I get someone over here to photograph this?”

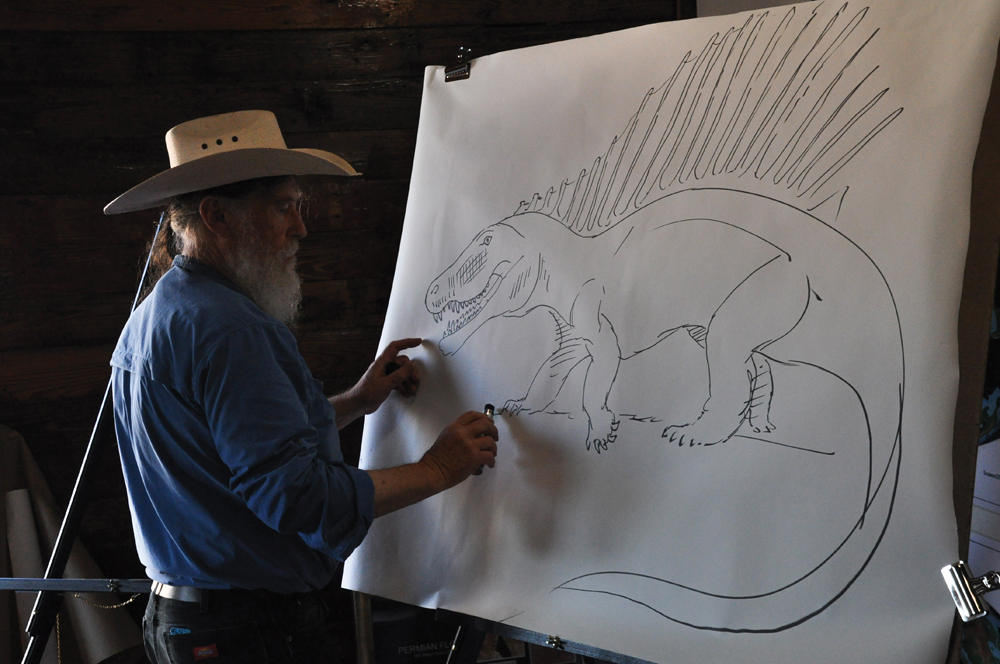

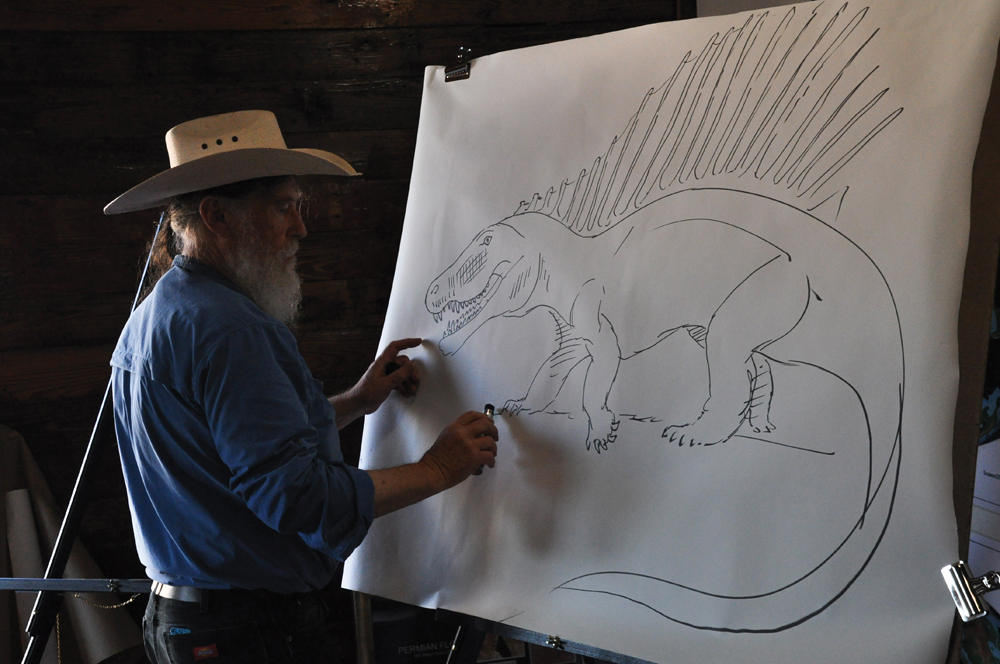

I place the vertebra back where I found it. Someone runs to grab note cards. A camera flashes, documenting the position of the newly exposed remains. Amid the bustle, Robert Bakker, the museum’s curator of paleontology and one of the most famous paleontologists of the modern era, sprawls on the ground, examining another bone. He looks up, the very picture of a classic paleontologist with his white cowboy hat, long, graying hair and bushy beard. “It’s definitely another Dimetrodon,” he says. “Maybe a Dimetrodon loomisi? That’s the one with a really slender, long neck. Could be that. And it’s beautiful. Needs a name.”

The two curators toss potential nicknames back and forth before settling, for no reason I can discern, on “Laslow.” The discovery has shifted the agenda for the afternoon; the initial plan involved cleaning blankets of mud from the plaster jackets. But the same rains that chewed at the quarry walls and coated the jackets in mud also washed Laslow’s remains into the open. The new goal is to document and collect them before it rains again, recording their original locations, tucking them into plastic bags, and readying them for transport to Seymour. There they will join a growing collection of fossils in the Whiteside Museum of Natural History, more pieces of an ecological puzzle that has bedeviled some of America’s top paleontologists for more than a century.

Travelers walking through ancient Seymour would have found themselves in an ecosystem defined by fierce competition between amphibians and their newly evolved cousins, reptiles.

Nearly all of the fossils in this quarry are Dimetrodon or similar “sail-backed” predators. It’s a concentration of flesh eaters unprecedented in the modern world, and a pattern that’s repeated in the vast majority of dig sites in Baylor County. Bakker and Temple want to find out why.

Seymour, pop. 2,652, is a blue-collar town nestled within the rolling hills and gentle bluffs along the Brazos River, guarded on the southern approach by ranks of enormous wind turbines. Downtown is a grid of small streets and dusty buildings around the intersection of two county highways, complete with local diners and fast-food joints. Beyond the residential streets, fields and longhorn paddocks stretch away toward empty horizon. The landscape bursts with new growth from the May rains; a thick blanket of waist-high grass, wildflowers and cedar crowds the ranch roads, the air humming with the whir of grasshoppers and cicadas. Scissor-tailed flycatchers zip like black-and-white bullets through the air, and collared lizards sprint in blue flashes across the road. After years of punishing drought, the overwhelming impression is of a place awakening from hibernation and eager to make up for lost time.

Belying its sleepy appearance, the town has played an important role in American paleontology since the 1870s, when collectors employed by the eminent Philadelphia naturalist Edward Drinker Cope combed the gullies of Baylor County. The 280-million-year-old Permian rock layers that Cope’s men found weathering out of the ground came to be called “red beds” for the distinctive crimson hue of their iron oxide-rich sediments. Locked inside those sediments were the remnants of creatures never before seen by scientists, including a plethora of skeletons belonging to a big predator with a long-spined sail.

In 1878, Cope gave the creature its official name, Dimetrodon, or “two-measured teeth,” a reference to the distinctive lengths of the animal’s fangs. Despite popular misconceptions, the animal was neither dinosaur nor typical reptilian predator. Dimetrodon, Cope realized, was a pelycosaur, an animal closely related to the ancestors of modern mammals. In his official description, Cope named three separate species within the genus, distinctions made possible by the sheer wealth of material coming out of the Baylor County deposits. According to Bakker, Cope also boasted that Dimetrodon was the most common animal in his collections, and though aspects of its anatomy confused him—“the utility [of the sail] is difficult to imagine,” he wrote in an 1886 monograph—he apparently never wondered why the animal itself was so pervasive around Seymour.

The strange ubiquity of Dimetrodon fossils was easy to miss in a paleontological tradition that placed more emphasis on comparative anatomy than statistical studies of dead ecosystems. In 1909, paleontologists from the University of Chicago got permission to poke around the Craddock ranch and stumbled across the mother lode, a series of sites utterly packed with bones. After working the sites for a few years, the Chicago paleontologists were followed by workers from museums including the American Museum of Natural History and the Smithsonian. After a few decades of collecting, David Temple said, most of the visiting museum crews had assembled more Early Permian fossils than they knew what to do with. Excavation of the still-productive Seymour beds fell off. Leading paleontologists such as Alfred Romer, one of Bakker’s old professors at Harvard, contented themselves with studying the skeletons they already had.

Then, in 2004, the Houston Museum of Natural Science began planning the expansion of its fossil hall, an upgrade to be shepherded by Bakker. From the 1960s on, Bakker had established himself as a dynamic and controversial figure, responsible in large part for popularizing the idea that dinosaurs were warm-blooded animals. But while dinosaurs established his place in the public eye throughout the 1980s and ’90s—during which he wrote two popular books, appeared in innumerable documentaries, and consulted on films including Jurassic Park—his research interests ranged further afield, encompassing paleoecology, the history of science and, crucially, the Permian fauna of the red beds. He was eager to give Dimetrodon and its neighbors a central place in the new fossil hall, Bakker told me. But according to Temple, there was just one problem: The Houston museum didn’t have any Permian vertebrate fossils to display. “All we had was a painting of a Dimetrodon on a life-through-time mural,” Temple said.

Both men agreed that it was time to go back to Seymour. Temple, an archeologist by training who had wandered into paleontology during his rise through the museum ranks, led the charge. He soon discovered that the Craddocks had married into the Whitley family, who now own the Craddock ranch. So Temple gave Bill Whitley a call. “I told them about the museum and what we were doing,” Temple recalled, “and asked what it would take for us to come to an arrangement.” Though Temple didn’t know it at the time, a paleontologist from a different museum was sniffing around as well. After the other paleontologist missed several meetings, an annoyed Whitley told Temple that actually showing up would be a great place to start. “We were there the next day,” Temple said. The resulting partnership has lasted 11 years, filled Houston’s new Morian Hall of Paleontology with Permian fossils, and led to the creation of Seymour’s own local museum, the Whiteside Museum of Natural History.

I arranged to meet the Houston dig crew at the Whiteside on June 6, a date that marked the museum’s first anniversary. It’s a handsome little establishment in a repurposed car dealership, packed with bones and models of animals both prehistoric and contemporary. A life-size T. rex head bearing an uncanny resemblance to John Travolta glowers from one of the walls. The museum’s preparation lab occupies a back room lined with unopened plaster jackets. Another room contains tanks of live reptiles, ostensibly to show visitors examples of body types common across the Permian era, but in practice because Whiteside Director Christopher Flis really likes lizards.

Flis is a tall, rangy man with a youthful face and a background developing museums with the Houston Museum of Natural Science. He and collections curator Mallori Hass participated in the Houston excavations for years before being hired by Clyde Whiteside, a local judge, to build Seymour a museum of its own. “The skeletons and fossils that were dug here had always left the town and never came back,” Flis said. “They went to the Smithsonian or Harvard or Princeton. So for this museum, the idea was to have the skeletons here stay here forever.” The museum represents a research model at odds with the past colonial-style expeditions of big Eastern and Midwestern institutions. While the Whiteside isn’t officially affiliated with the Houston museum, the presence of Houston-associated personnel has produced benefits for both: Houston got choice specimens for its fossil hall, and the Whiteside gets support in its collection and preparation efforts.

Early on June 7, I accompanied Flis, Bakker and a few other members of the Houston crew out to one of the main sites, a dig located a few miles from the Craddock ranch. We piled into a caravan of SUVs that bounced and juddered down a bumpy track and into a warren of juniper-shrouded arroyos littered with fine sand and white boulders. The rest of the morning was spent prospecting and digging out a huge plaster block containing a nearly complete Dimetrodon skeleton dubbed “Mary,” which Flis suspects belongs to a new species. The rocky ground baked under the hot sun, and the air rang with pickaxes and laugher as volunteers chipped stone from the plaster jacket. Bakker and a few others scattered to pick along the dry washes, collecting bits of bone. Every now and again, Bakker stooped and plucked a small fossil from a scatter of identical pebbles. He listed his finds aloud as he worked—“neural spine, baby Dimetrodon, piece of rib”—before a volunteer handed him an apparently unremarkable scrap of bone. Handling it, Bakker suddenly cried out in excitement; it was a piece of Diplocaulus, a flat little boomerang-headed salamander previously unknown in that deposit.

Bakker has an academic’s tendency to launch into lectures at the drop of a hat, switching subjects and thoughts mid-stride and peppering his discourses with Socratic questions. And yet his excitement is contagious. Of course he likes big complete skeletons, he told me. Everyone does. But what really fascinates him are the small scraps, the bits that eventually provide a more complete picture of the ecosystem—who’s eating whom, who’s burrowing or defecating, and all the other messy business of existence. “My old professor Alfred Romer used to say that he would just throw away any vertebrae that weren’t perfect,” Bakker said, eyeballing a promising-looking stone. “That’s ridiculous. Perfect bones tell you almost nothing. Nothing about the animal’s life or how it died or what happened to it afterward.” Bakker prefers a more statistical approach, collecting data points and trying to divine the truth via the aggregate of remains. It’s why he goes crazy for the little fragment of Diplocaulus: It’s not supposed to be here in this environmental deposit. And if it’s not supposed to be here, then there’s something new to learn. We know what Diplocaulus looked like, more or less. But we’re still trying to figure out almost everything else about it.

The world of the Early Permian remains around Seymour would have been, to modern eyes, an alien place. Two hundred and eighty million years ago, at the time of the red beds’ deposition, the world’s landmasses were locking together into the supercontinent of Pangaea. The vast swamps of the Carboniferous Period dwindled in the drying climate, taking with them their elevated oxygen levels and giant insects, and ushering in the dominion of the first great land vertebrates. In those days, Bakker said, Baylor County was an interlocking sweep of seasonal ponds and turbid rivers with marshes occupying the basins and tree ferns foresting the drier uplands. Each area of this patchwork laid down subtly different sediments, as many as nine different fossilized soil layers.

Nearly all of the fossils in this quarry are Dimetrodon or similar “sail-backed” predators. It’s a concentration of flesh eaters unprecedented in the modern world.

Travelers walking through ancient Seymour would have found themselves in an ecosystem defined by fierce competition between amphibians and their newly evolved cousins, reptiles. Hordes of the crocodile-salamander Eryops hunted along the edge of the black waters, while Diplocaulus scudded along the muddy bottoms. The eel-shaped river sharks Xenacanthus swam flooded channels in pursuit of silver fish, their heads armed with a backward-facing venomous spine. To the shores of the swamps came groups of Edaphosaurus, a 10-foot long, blunt-headed herbivorous reptile with a great sail on its back and a crocodile-like tail. Little armored amphibians trundled through the ferns in their wake, snapping up insects disturbed by the browsing giants. The traveler might glimpse a rare Diadectes, a hefty burrowing reptile that grazed in the uplands. He would certainly see one of several species of Dimetrodon, basking, prowling, or waiting in ambush for unwary prey.

Paleontologists studying the red beds puzzled over Dimetrodon’s ubiquity for years. No modern land ecosystems support that many apex predators. “If you go on a wildlife-watching tour in Africa,” Bakker said, “you will see on average 100 zebras per lion. Which is what you would expect. But what would it mean if you saw 100 lions per zebra? There’s something wrong with that picture.” And yet the equivalent disparity is present in the red beds, not only with Dimetrodon, but predators Eryops and Xenacanthus as well. While large herbivores such as Edaphosaurus and Diadectes also appear in the deposits, they’re uncommon.

Some scientists attempted to work around the problem by dismissing the Craddock beds as an anomaly, Bakker said, a data set suffering from what he called “Rancho La Brea syndrome,” which describes bone beds comprising mostly carnivores. Such deposits usually mark places where bogged-down prey or carrion attracted waves of predators, which, as in the case of the famous La Brea tar pits, quickly found themselves trapped as well. To determine if the Craddock deposits were similarly skewed, Bakker said, the Houston crew looked at dozens of isolated sites around the ranch. Most of these sites were composed years apart from each other. Everywhere they looked, Bakker told me, the results were the same: “No matter where you would go in the red beds—little tiny ponds, little tiny streams, plains the most common animal is the top predator.” Moreover, Bakker pointed out, more than 40 percent of the bones from the Craddock digs had been chewed to hell and back, suggesting that Dimetrodon played an ongoing role in the ecosystem.

What, then, was it eating? Several details of Dimetrodon’s anatomy suggest that it was a relatively quick land-based animal, Bakker said. Theoretically, you’d expect it to be hunting other land-based creatures, much as a lion skeleton suggests an animal better suited to prowling hills than swimming. But bones can be deceiving. The answer, Bakker said, was found by looking at fossil teeth. Dimetrodon, like many mammal relatives, often shed teeth in the course of dining. The result is the paleontological equivalent of shell casings from spent bullets. “If you look where we have shed Dimetrodon teeth,” Bakker told me, “where they’re actually feeding, it’s not on dry land. It’s either in ponds or near ponds.” In addition, the remains of aquatic animals often bear the telltale marks of Dimetrodon fangs, indicating that they’ve been chewed in a manner closely resembling the mastication of Dimetrodon’s mammalian relatives, wolves and hyenas. Which means, Bakker said, that instead of regularly attacking land-based browsers such as Edaphosaurus or Diadectes, the sail-backed hunters were most likely eating amphibians and sharks.

Dimetrodon, like many mammal relatives, often shed teeth in the course of dining. The result is the paleontological equivalent of shell casings from spent bullets.

According to Bakker, this conclusion had been predicted by paleontologist E.C. “Shorty” Olson in the 1950s. But nobody was listening at the time, and the idea was soon forgotten. Now, on the strength of chewed shark skulls, shed teeth and other clues, it’s looking more and more likely that the top predator of the Craddock ranch regularly swam for its supper. A big Dimetrodon might occasionally catch and kill a Diadectes or a smaller sail-back, Bakker said. But when the seasons turned dry and the ponds and rivers dwindled, Dimetrodon came slithering along to snatch up boomerang salamanders, crush the skulls of Eryops, and wade into the evaporating waters to do crashing battle with the spined river sharks. With their cold-blooded metabolisms, Bakker said, the top predators of the Permian likely needed only a few big meals a year. A drying pond, complete with trapped amphibians, fish and sharks, would provide an irresistible feast.

Conversely, Bakker and Temple have found Dimetrodon bones gnawed, not only by their fellow hunters, but by sharks. Bakker told me he suspects that somewhere in the Craddock lies the skull of a Dimetrodon that misjudged a strike and was speared by a venomous Xenacanthus spine. Or maybe not. The vast majority of Dimetrodon fossils are scraps, chewed or weathered. What killed them—old age, thirst, drowning, predation or poison—we may never know for sure.

And yet the Craddock produces its share of well-preserved skeletons, too. Often they come clumped in aggregations of bones, and it’s these sites that receive the most attention from paleontologists and collectors, come to free their ancient evolutionary uncles from the rock.

Workers spend very little time preparing fossils in the field. Most of an expedition is spent eyeballing the ground for hints of bone weathering out of the surface. Find something good and you have to carefully determine the extent of the remains, coat them in plaster to protect them from the elements, and break the block away to be taken to a lab. Once there, the bones are cleaned in preparation for study or display. Sometimes the effort to free jackets from the rock uncovers still more skeletons, which must be preserved before the original jackets can be removed. A really productive site can turn into a logjam of plaster and tools, and diggers have to triage, taking out as much as they can as quickly as they can, and trusting the plaster jackets to preserve what they leave behind. Bakker often jokes that the most important law of fieldwork is that the most important specimens, the ones that require instant attention, turn up only when the temperature has hit 130 degrees and you’ve decided to leave.

After returning from the Mary site to the Whiteside Museum, we grabbed a quick lunch and drove out onto the Craddock ranch, over a track hemmed in by thick grass. The occasional horned toad sat in the shade of a mesquite, watching us pass in dignified stillness. We piled out onto the second site, with five plaster jackets still in the ground and a blue tarp covering part of the quarry wall. We loosened dirt with screwdrivers, spades and knives while Bakker sang dirty sea shanties in his quiet, precise voice.

And then David Temple peeled back the tarp and we saw Laslow’s bones spilling out of the hillside. Nor were those the only gifts from the rain. The volunteers began finding other fossils in the scree: bits of Diplocaulus and other amphibians shining opalescent blue in the sun; the scrappy remains of tiny Dimetrodon hatchlings; even the odd bone from another pelycosaur, a long-jawed predator called Varanosaurus. Of Laslow, the Dimetrodon loomisi, the final tally is the better part of a backbone, from the tip of the tail to scattered remnants of abdomen, thorax and neck.

As they worked, I walked out to the spoil pile outside the quarry and looked over the landscape of canyons and hillocks, all of it swept up in rare green. Something glimmered close to my feet. I looked down to see a Dimetrodon neural spine eroding out of the dirt, its surface cracked, and beyond it another, and another, mixed in with tiny fragments of bones beyond counting. Far beyond, the great wind turbines built by dead Laslow’s most distant kin turned above the scrubland, ceaseless as the passage of time.