Blood Aces Shows Texas Gangster Benny Binion Knew How to Hold ‘Em

A version of this story ran in the October 2014 issue.

Come November, nine poker players—survivors of a 6,683-entrant pool—will face off at the final table of the 2014 World Series of Poker, gambling’s marquee event. A global ESPN audience will witness the crowning of this year’s Main Event champion, who will take home a $10 million paycheck.

By Doug J. Swanson

Viking

368 pages; $27.95

The gambling world attracts more than its fair share of colorful personalities, and modern poker is no exception: Phil Hellmuth is known as the “Poker Brat” for his churlish table demeanor; Phil Ivey, widely regarded as the best poker player in the world, began playing Atlantic City casinos with a fake ID at 17; Huck Seed is said to have once lost a $10,000 proposition bet when he failed to remain standing in the ocean, submerged to the neck, for 24 consecutive hours. For spectators and historians, personality and lore are big parts of the tournament’s draw.

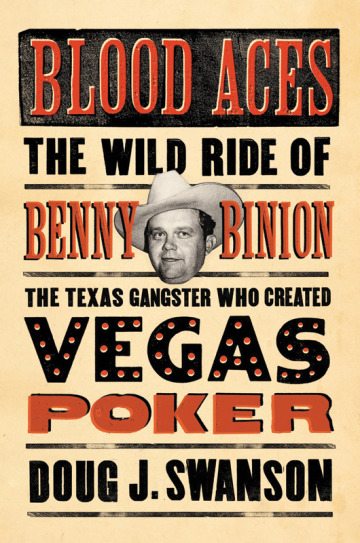

But it’s a good bet that many of the young poker pros at this year’s World Series of Poker have little idea how the tournament began. They’d do well to pick up a copy of Blood Aces: The Wild Ride of Benny Binion, The Texas Gangster Who Created Vegas Poker. So would anyone else inclined toward well-honed stories about gambling, Prohibition, Dallas, Las Vegas, bootlegging, murder, revenge, gangsters, graft, movie stars, drugs and family. But above all else, Blood Aces is the unlikely tale of a sickly, illiterate, small-town boy who bulled his way into control of a multi-state money machine using equal parts charm, cunning and brutality. As Doug J. Swanson’s exhaustively researched and artfully written account demonstrates beyond all doubt, they don’t make ’em like Benny Binion anymore.

Born the son of a North Texas stockman in 1904, Binion suffered poor health as a child—he’d had pneumonia five times by the time he was 5—setting the stage for his life to come. His father pulled him out of school at 10 (he’d yet to clear second grade) and immersed him in the life of an itinerant horse trader, where young Benny learned the importance of playing the angles. The teenage Binion cut his teeth working for road gamblers and immediately recognized that the smart play lay in being the house, not betting against it. After a Prohibition-era stint running booze in El Paso, Binion moved to Dallas and, by the tender age of 24, began augmenting his moonshine income with an illegal “policy” game—a simple lottery with huge profit margins. Thus began a career that would see Binion establish gambling empires across two states, built first on lotteries, later on dice and finally on legal gambling in what became known—aided in no small part by Binion’s preternatural combination of largesse and ruthlessness—as Sin City.

Writ large, Binion’s life reads more like fiction than fact. He confessed to killing two business rivals but never served time for murder, and was linked, but never pinned, to a number of other assassinations. One longstanding Binion adversary, a Dallas racketeer named Herbert Noble, survived 11 attempts on his life, a Looney Tunes-like saga that ended in an appropriately cartoonish manner with attempt No. 12, when Noble was blown sky-high by a bomb as he fetched his mail.

Describing the aftermath of the investigation, Swanson writes that “By the end of the day, [the police] could have put all their clues in a suitcase and had room left over for what remained of Noble.”

Binion established gambling empires on lotteries, on dice and finally on legal gambling in what became known—aided in no small part by his preternatural combination of largesse and ruthlessness—as Sin City.

“There was plenty of room in the Cadillac, he told the agents. The seats were soft, and a man could stretch out and relax if he wanted. Why didn’t they pile in the back of his car and ride with him all the way to Dallas? Make it easier on everybody.”

“This offer,” a bureau memo later said, “was declined.”

Perhaps the most intriguing aspect of Binion’s complex personality—and the one most responsible for his enduring legacy among gamblers—was the inclusionary and pragmatic manner in which he treated his customers. Way back in his Dallas policy-game days, Binion had distanced himself from the Ku Klux Klan, despite that organization’s influence among the city’s power brokers, saying, “I don’t believe in hanging my customers.” Later, after Binion’s Horseshoe casino in Las Vegas became known as a mecca for high-rollers, he insisted on offering complimentary food and drink to all gamblers, regardless of wager size.

That democratization of the gambling experience is at the heart of the World Series of Poker, which began in 1970 as a Binion stunt—a public, high-stakes game between a handful of poker legends—and quickly blossomed into a spectator event with one critical difference from other such spectacles: The spectators could buy (or win) access into the highest level of the game and compete against the best players in the world.

There’s a common suspicion among poker professionals that no one of their kind will ever again wear the World Series of Poker Main Event winner’s bracelet—that the sheer number of amateur entrants stacks the odds so high that even the likes of Hellmuth, Ivey and Seed can’t climb them. But those pros also know that amateurs earning huge paydays are ultimately good for business, in a rising-tide sort of way.

Whether they realize it or not, that’s a lesson they learned from Binion, a North Texas bumpkin who knew a thing or two about beating—and benefiting from—long odds.

To support journalism like this, donate to the Texas Observer.