Bomb’s Away

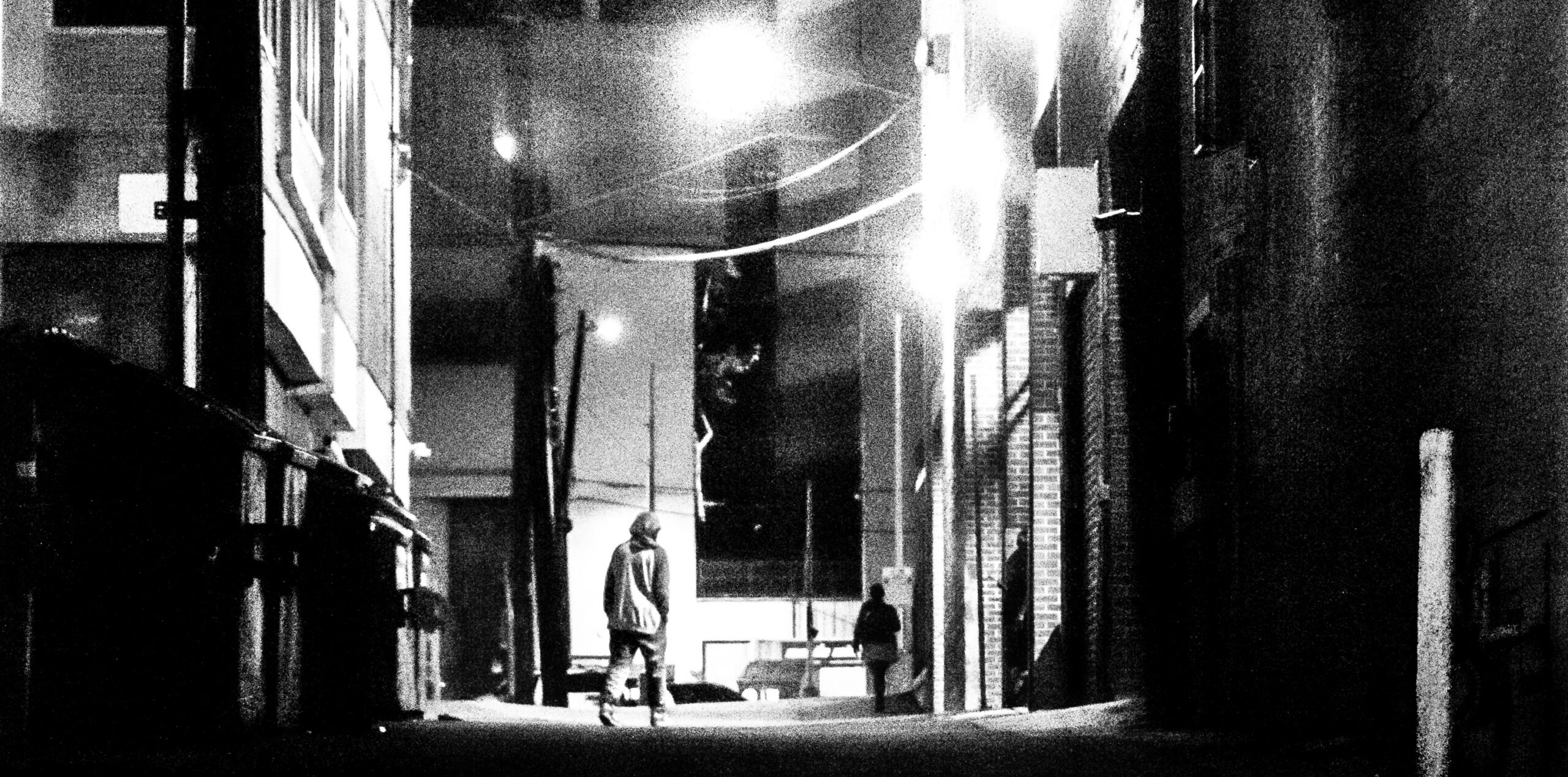

In a Ben Sargent editorial cartoon published in the Austin American-Statesman after the Nov. 26-29, 2008, Mumbai terrorist attacks, a heavyset man looks back over his shoulder at the reader. The man looks surly and uneducated. He is unshaven, prognathic and pug-nosed. He has on a worn winter overcoat and a longshoreman’s stocking cap. He has just entered the kind of run-down office where femmes fatales went to hire private eyes in 1940s and ’50s films noirs, only this office is identified on the opaque glass pane of its entrance door as A-1 SCHOOL OF TERRORISM. The heavyset man stands in front of a smaller inner door identified as the ADMISSIONS OFFICE. To his right, two open cardboard boxes sit on a wooden desk. A sign posted on the cracked wall features a thick black arrow that points down at the boxes. Above the arrow, bold letters instruct prospective students of terrorism: DISPOSE OF HEART and/or BRAIN HERE.

In The Dynamite Club, Yale historian John Merriman describes the historical setting and background of what he argues is the first modern act of true terrorism. At 9:01 on the evening of Feb. 12, 1894, 21-year-old French anarchist Émile Henry, who earned his baccalauréat in science from the Sorbonne in 1888, threw a dynamite bomb he had made into the crowded Café Terminus in Paris. A small orchestra had just started playing “the fifth piece of their first set” when Henry threw his bomb.

Merriman’s account enables us to identify the false stereotypes in Sargent’s cartoon. This is no small gain in what we, as citizens, need to know about terrorism.

The chief European anarchist proponents of violent “propaganda by the deed” who influenced Henry–the Russian Peter Kropotkin, fellow Frenchman Paul Brousse and Italian Errico Malatesta–had well-educated minds and, as Merriman makes us see, sympathetic hearts. They would not have been mistaken for waterfront goons. Merriman cites a front-page story from the Feb. 15, 1894, issue of the French republican newspaper Le Matin to show how troubled conservative middle- and upper-class citizens were by the fact that Henry was young, clean in appearance, clearly bourgeois and genuinely intellectual–in short, not a stereotypical “vulgaire brute.”

Understanding terrorists is a first condition for effectively combating terrorism. We have to get to know how terrorists think and act and why they believe, fanatically, what they believe. However, the very process of trying to get inside the hearts and minds of terrorists is stigmatized. Intellectual empathy, even for the purpose of gaining understanding that can ultimately improve our own security, is usually viewed with suspicion. Questioning why terrorists attack people like us may lead to answers that call for us to examine our own roles in creating and maintaining the social, economic or political conditions that give rise to terrorist acts.

This examination is what makes The Dynamite Club so important. Merriman demythologizes Émile Henry and the loosely organized international group of anarchist thinkers who inspired and supported him. Merriman also comments, without being heavy-handed, on the conditions European anarchists were trying to change.

The main thing they were trying to change was the extreme disparity in wealth and power that in Paris alone kept hundreds of thousands of men, women and children in abject, anonymous and inescapable poverty. As one anarchist commented, “What a beautiful society when the budget of the state spends four million francs on the opera each year as a subsidy … while poor people try to get by in the streets and public places without anywhere to live.” Merriman contrasts the beautiful center of Paris with the “enormous suburbs … full of sadness and menace.” In those neighborhoods, the rate of tuberculosis was five times greater than in the center. Given the financial scandals of the Third Republic, most workers felt an “[u]tter disgust for parliament” and “ignored elections, which had done nothing to improve their lives.” Anarchists aimed to shake members of the bourgeoisie out of their ignorance about the economic exploitation and intolerable social conditions that made their comfortable lives possible, and to shake downtrodden members of the working class out of their political apathy. Émile Henry believed the comfortable pleasures enjoyed by the thoughtless bourgeois gathered in the Café Terminus were based on the miseries of the working class.

Henry was arrested right after he tossed his bomb, which killed one man, wounded 20 others and, according to Merriman, threw government officials, police and well-heeled Parisians into a panic. Henry was quickly put on trial, found guilty, and guillotined on May 21, 1894. Throughout his trial, he testified rationally and logically. Merriman quotes selectively from Henry’s long, stylish and well-reasoned final statement, admirably withholding explicit judgments. The online Anarchist Encyclopedia reproduces the complete defense, calling it “a very powerful and moving piece of literature.”

Soon after Henry’s arrest, Merriman recounts, “a violent proclamation printed in London turned up, asking its readers to slaughter bourgeois and spread the blood of the murderers who were starving the poor to death.” There was legitimate fear that other anarchists might do to any well-to-do European what Henry had done to the unlucky people who happened to be eating, drinking and talking in the Café Terminus.

According to Merriman, the anarchists who preached and practiced social and political violence from the 1870s into the early 20th century were far from our standard terrorist stereotypes. Kropotkin, who first used the phrase “propaganda by the deed” at an anarchist congress in August 1878, was “a geographer and a prince, the son of a Russian army officer of the nobility” who espoused a kind of anarchist communism based on the idea that destroying the oppressive machinery of the state would allow the innate morality of individuals to emerge in smaller, local, social groups. Merriman describes Kropotkin’s optimism about the essential virtue of human beings as contagious. Kropotkin’s vision had wide influence, and not just on society’s fringes. Oscar Wilde once declared that Kropotkin lived one of the two “most perfect lives” he had ever observed.

Though Kropotkin later had “second thoughts about … the deaths of innocent victims in terrorist attacks,” he saw the need for anarchists to be more than “idle word-spillers.” The reasoning among anarchist thinkers from the 1870s into the 1890s was that violent deeds alone could “awaken ‘the spirit of revolt’ in the masses” and “offer hope to the downtrodden.” Kropotkin, acknowledging his privileged position, eventually took the position that “we are no judges of those who live in the midst of all this suffering. … Personally I hate those explosions, but I cannot stand as judge to condemn those who are driven to despair.”

Anarchist theorist Errico Malatesta in 1921 summed up the lifelong conviction that inspired his revolutionary acts. In his view, it was repressive social violence that denied the working poor and their families the means of living decent lives. He believed that it was “necessary to destroy [such violence] with violence.” He started out as a medical student at the University of Naples but came to see that “so-called intellectuals,” because of their education, family background and class prejudices, could be “tied to the Establishment” and thus desire “the subjection of the masses to their will.”

Seeing the miserable conditions in which the poor lived, worked and died, Malatesta considered all anarchist acts good, so long as they didn’t exceed “the limit determined by necessity.” Given anarchist rejection of hierarchical structures, imposed ideologies and authoritarian rules of conduct, Malatesta’s reasoning, like Kropotkin’s, provided lots of moral wiggle room.

Malatesta also eventually rejected the indiscriminate use of bombs in the cause of social and political revolution. Malatesta came to believe that, in Merriman’s summary, “Anarchists should operate like a surgeon who cuts where necessary but avoids inflicting needless suffering. Anarchists should continue to be inspired by love, which remained at the heart of their project: to serve the future of humanity.”

According to Merriman’s account, Malatesta’s widely circulated call for moral restraint in choosing targets angered Émile Henry, who viewed the use of bombs against officials and members of the comfortable classes as an “individual initiative” that offered “the most effective way of striking at bourgeois society.” Directing deadly violence at members of the bourgeoisie, in Henry’s opinion, would shake them from their complacent complicity in maintaining a social order that left too many of their fellow citizens without the wages, food, housing, education and health care to maintain a modicum of human dignity.

Émile Henry’s father, Fortuné Henry, was “elegant and proper … intelligent and educated.” He passed on to his son his sensitivity to social injustice and his political activism.Fortuné Henry was “on the barricades in Paris during the revolution of 1848,” and after being arrested and imprisoned for militant acts in 1863 and 1867 he was elected to a prominent leadership role in the workers’ revolt known as the Paris Commune in 1871. When the Commune was besieged by French army forces from Versailles, Fortuné signed an order that “three hostages drawn from the clergy, the judicial authorities, the army, or the bourgeoisie ‘be executed for each Parisian civilian killed by shellfire from the attackers.'” He escaped to Spain while an estimated 25,000 Communards were massacred or later executed. He was sentenced to death in absentia.

Émile Henry was born Sept. 16, 1872. He was an award-winning student from a young age, receiving high grades and glowing reports for conduct, hard work, character and honesty. He attained a baccalauréat in science, with honors, at age 16. He passed the written examination for entrance to the elite École Polytechnique but failed the oral examination under distracting circumstances. Still, he immediately redirected his well-developed talents. Taken on as an assistant by an uncle whose reputation as an engineer gained him contract offers in Europe and Africa, Henry wrote home from Italy about his own bright prospects. He looked forward to a productive life of work and travel.

Henry quit working for his uncle when asked to do what he considered spying on workers–an indication of how deeply his father’s sympathies and his own socialist and anarchist reading had affected him. Merriman affirms that a London newspaper “got it right” in tracing Henry’s outlook to the fact that he was “the son of a man who had seen in 1871 thousands of working men, women and children shot down in heaps, while well-dressed men and dainty ladies struck the bound prisoners with canes and parasols, shrieking, ‘Shoot them all.'”

Once in Paris, Henry, like other anarchist thinkers, saw that the enormous disparity in wealth and standard of living between the urban poor and the middle and upper classes, which had led to the formation of the Commune, still existed. In 1891, Paris had a population of 2.5 million. Recessions in 1889 and 1892 left more than 200,000 workers unemployed.

The living conditions of working-class families in the poor districts that ringed the fashionable parts of Paris were miserable, and anarchists like Henry commiserated deeply with the urban poor. Merriman calculates that a typical working-class family of four, with all four members working, could bring in about 760 francs per year, but required 860 francs for poor clothes, poor food and tiny apartments without heat or running water. As Merriman puts it, “[t]he belle époque was not belle for most French men and women. … Millions still lived in abject poverty.”

Henry learned firsthand in Paris the lessons his father had learned in 1848 and 1871. The state supported economic disparity with its laws and courts. Government leaders directed soldiers and police to enforce laws that kept the poor hungry and embittered. Society gave those who “made it” a stake in making sure that the status quo, which now favored them, remained in effect.

The act that pushed Henry over the edge was the execution of Auguste Vaillant. Thirty-two years of grim poverty had made Vaillant an anarchist. Vaillant became unemployed in Paris in the winter of 1893. His wife and daughter were cold and starving. He threw a small bomb, which he designed to hurt but not to kill, into the Chamber of Deputies on Dec. 9, 1893.

In reaction, harsh new laws were passed criminalizing any writings “sympathetic to anarchism.” Kiosks were forbidden to sell socialist newspapers, and 248 people were arrested on suspicion of being anarchists. The number of arrests, according to Merriman, “gave the impression that the government and the police force were persecuting the poor on behalf of the rich.” Vaillant was arrested, tried, convicted and put to death in less than two months. Given that his bomb had killed no one, and that the unemployment, poverty, hunger and cold affecting thousands of working-class families had driven him to his act, intellectuals and workers alike viewed Vaillant as a “victim of the bourgeoisie.” This was Émile Henry’s view, and he propagated it with his own bomb seven days after Vaillant was guillotined.

In his own defense, Henry declared that the state, by guillotining Vaillant and making hundreds of arrests that suggested all anarchists were responsible for Vaillant’s act, had acted in support of the bourgeois, who profit from the labor of workers. It was therefore time for anarchists and the suffering poor “to show their teeth.” Henry argued that anarchist bombings like his extracted vengeance for the unacknowledged murders of poor children, who “slowly die of anemia, because bread is rare at home”; poor women, who are worn out in workshops for “forty cents a day”; and men who are “turned into machines” and then “thrown into the street when they have been completely depleted.”

Reading Merriman’s history of Émile Henry may not make us sympathetic to terrorists, but it should make us aware of our role in creating and tolerating conditions that breed what we call terrorist “hatred.” It was not mere moral relativism or radical sophistry that led Émile Henry to reason, “To those who say: Hate does not give birth to love, I reply that it is love, human love, that often gives birth to hate.”

Tom Palaima is Dickson Centennial Professor of Classics at the University of Texas at Austin, where he teaches seminars on the human response to war and violence.