Tough Love and Discipline in Brownsville ISD’s Boot Camp School

When Brownsville public school students step out of line, they're marched off to boot camp. But does military-style discipline help or harm?

A version of this story ran in the June 2013 issue.

They start arriving at 6 a.m., Brownsville’s gang members, brawlers and foul-mouthed youth, truants and scofflaws who have violated the student code of conduct. Here, they will learn a thing or two about conduct.

Within a week, they know the drill. First they line up for intake screening, the boys in double-file, girls single-file beside a wall, and for the first of many times in the next 10 hours, they wait. When they reach the front of the line, they turn their pockets inside-out, take off their shoes, raise their arms and submit to a pat-down.

This is how each day begins at the Brownsville Academic Center—“BAC,” in the acronym-rich military shorthand popular here, or just “the boot camp,” as it’s known around town. It’s a public school campus in the Brownsville Independent School District, but there are no students here—only “cadets.” The men and women in head-to-toe desert camouflage, checking the kids for contraband, are “drill instructors” or “DIs.” In these early-morning hours before the teachers arrive, the school and everyone in it belong to them.

Clear of the intake screening, cadets find their places in the school’s courtyard, drop their belongings at their feet, and wait some more. They range from sixth-graders to seniors in high school, all in matching gray T-shirts and shorts. Their haircuts are the same—short buzz cuts for the boys, the girls’ hair pulled back in buns—and only their size and sneakers differentiate them.

They don’t come here with much. The things they carry fit in neat bundles at their feet: dark camouflage pants, shirts and hats tied up in a cloth belt, a canteen, and a pair of black boots. Most have worn copies of a school handbook. A couple have library books: Goosebumps or Captain Underpants.

Most of the kids stand in place quietly, but as the intake drags on, a few start messing around. “Eastside!” comes a boy’s voice. “Southside,” another calls back. They repeat this and, the silence broken, a couple of boys begin joking with one another until a drill instructor catches them.

“Knock it off,” he says.

“Sir, yes sir,” they murmur.

“I didn’t hear that! Louder than that.”

“Sir, yes sir!”

It’s a radical, and rare, approach to school discipline that Brownsville has employed for 15 years. Brownsville ISD’s boot camp has survived the bad press and scandals that shuttered most other juvenile boot camps years ago. It’s tough to get a hard count, but of Texas’ 1,000-plus districts, only about five others have anything like BAC, and none this big.

Principals in Brownsville can send kids to boot camp for any misbehavior serious enough to warrant out-of-school suspension: bringing weapons to school, or just cursing in class. BAC provides tough love for gang-bangers and class clowns alike. Sometimes it’s just a stop for kids before they drop out or end up in the juvenile justice system. Until a few years ago, Brownsville ISD police issued misdemeanor tickets to more students than any other district its size in Texas, a prime example of the trend toward criminalizing student misbehavior—the school-to-prison pipeline.

The boot camp’s critics say this pipeline runs right through BAC, that every time students are pulled out of regular class and booked into a disciplinary program, they get the message that they aren’t good enough. And the critics contend that BAC, with a bunch of camo-bundled sixth-graders just five miles from the ultra-militarized Mexican border, is grooming kids for the military or the Border Patrol.

But advocates for the school say the boot camp is designed to catch kids before they end up in that pipeline to prison, and to turn them around. It’s character training and structure, in assignments of just 30 or 45 days, for kids who need more than their neighborhood school can offer. Take a look at BAC, they say, and it’s clear this place isn’t about breaking spirits or making soldiers—it’s about learning to love the rules.

Take a look inside a morning at Brownsville ISD’s boot camp:

It’s early morning and the sun is still hidden beyond the Gulf horizon, the sky a deep blue. The sweet but unmistakable smell of sewage blows through the courtyard, where the kids gather for exercises and marching practice. The courtyard is the school’s signature feature, open at the sides and topped by a three-tiered metal pagoda painted dark green, olive and blue. The roof is corrugated metal, supported by massive beams bearing inspirational words stenciled in gray: motivate, communicate, decisive.

Patches of grass lighten the mood, and they are immaculate, like the rest of the school. The campus was littered with stray rock when it opened in August 2012, but it wasn’t long before the kids who stepped out of line and earned “beautification duty” had the rocks cleaned up. Kids who spit on these floors learn to use a mop.

At morning exercises, platoons of students are doing jumping jacks, neck rolls and mountain climbers, shuffling their feet in the push-up position. A drill instructor named Diaz, a hulking man built for yelling, keeps the rhythm: “UNH! OOGH! HREE! UNH! OOGH! HREE!” When an exercise is complete and it’s time for the group to move, he counts down from 10. After “UNH!” the students quit shuffling and answer in unison: “FREEZE, CADET, FREEZE!”

In the cafeteria, the highest-ranking cadets have changed into their battle dress uniforms of dark camouflage for breakfast. The meal is a tightly regulated enterprise that begins, like everything else, with waiting. The cadets wait outside the cafeteria before they’re ordered to go in. Then they wait along the cafeteria wall, staring at a cardboard cutout of Brett Favre holding a glass of milk, before advancing to the counter for a tray. When they reach their seats, they wait some more until they’re told to sit, all on the same side of the table so they won’t be tempted to talk. When a drill instructor barks, “Secure plastics!” the cadets unwrap their plastic forks, straws and napkins, and the DI walks sternly down the row collecting the plastic wrappers. “Ready … eat!” comes the call, and only then do they unwrap their PBJ pockets and poke straws into their milks. They eat with brutal efficiency. The only mealtime sounds are crinkling plastic wrappers, humming kitchen appliances and walkie-talkie chatter between the DIs.

Even more than the morning frisk or the marches around the yard, this is the drill instructors’ shining moment, a typically social occasion distilled to its essence. In other schools, meals might last 45 minutes or an hour. Here they’re 15 minutes, half that time spent on logistics like ensuring the plastics are, in fact, secure.

You can trace procedures like this at BAC to one man, Orlando Salinas. A veteran of the first Gulf War who’d gone on to teach, he was running a nighttime program for Brownsville ISD high-schoolers when an assistant superintendent asked him for thoughts on addressing the district’s dropout problem. Salinas, still serving in the Texas National Guard, decided lack of discipline was the biggest problem, and he found inspiration in the best discipline instruction he knew of. “That military piece was always a means to an end,” Salinas says. “The end was always education.”

In the late 1990s, Brownsville ISD already had an alternative school for disciplinary referrals. Salinas’ venture, which he named the Teen Learning Center, was a more extreme option—students served out semester- or year-long suspensions in his school, much longer than a stint at BAC now.

Salinas drafted principles to guide his new school, housed in portable trailers on a patch of dirt. The school would be a tough place, but not one for constant punishment.

“We endeavor to return these students to mainstream education and thus produce self-directed life-long learners,” read his mission statement, in part. The program would be “an exhausting daily routine” from 6:30 a.m. to 6 p.m., with students in a platoon structure, in uniform, led by drill instructors, teachers, a probation officer, counselor and nurse. Salinas set aside space so probation officers, social workers and teachers could talk together, to get a fuller picture of what a student was going through. He hand-picked his teachers from around the district, and drove a U-Haul trailer to San Antonio to buy uniforms in bulk—50 cents for a set of pants, shirt, hat and boots. His first class of students unloaded the trailer and sorted them out by size.

He wanted kids to grapple with strict school routines during the day, he says, then go back to the same friends and home life that led them into trouble. “If I take you out of your environment, it’s easy to change. You’ll change because your environment is different,” he says. “I want these kids to change while they’re in an environment [that’s familiar], so that the change is lasting.” A kid might show up at school drunk or high, he figured, but once they try the daily two-mile run in that condition, they’re not likely to do it again.

He tracked graduation from and recidivism to his program, thinking he’d present his school as a case study in an academic paper someday. In the six years Salinas was at the school, the number of students returning for a second tour hovered around 5 percent.

In 2004, Salinas was called up for active duty in Afghanistan, and left his place at the school. He’s a general in the Texas Army National Guard today, living near Austin, but remains proud of the school he built 15 years ago. On his wall at home, he still has a gift from some old students: a handmade wooden shape of Texas bearing the school motto, “Discipline with dignity.”

Brownsville’s superintendent when Salinas left was Michael Zolkoski, a San Antonio native and a boot-camp-school evangelist in his own right who’d founded boot camps in three other districts. Zolkoski tapped longtime principal Sharon Moore to design a new, more intense boot camp model. Zolkoski named it the Brownsville Academic Center, and designed programs for short-term suspensions and more serious long-term interventions, all built to mimic the Boys Town model of tough love for tough kids.

At the time Salinas designed his Teen Learning Center, youth boot camps were a popular answer to problem kids in Texas, part of then-Gov. George W. Bush’s zero-tolerance approach to student misbehavior. (See “Too Black for School,” April 2010.) Most of those “scared straight” programs were residential facilities run by juvenile probation departments, and a few were collaborations with school districts. Most have since closed after studies suggested that boot camps do little to steer kids away from crime and after horror stories of violent drill sergeants and child abuse. A parent in South Texas’ Harlingen Consolidated Independent School District recently filed a complaint with the police claiming she was shoved by her daughter’s boot camp drill sergeant. One of Zolkoski’s own boot camps, the Tulsa Academic Center, modeled after Brownsville’s, became so violent and overcrowded after a year in operation that it cost him his job. (He’s now superintendent of El Paso’s Ysleta ISD, which doesn’t have a boot camp.) But Brownsville’s boot camp endured and thrived.

After the boot camp had been housed in drafty portable trailers for years, the district built a new campus for the BAC with $8 million in local bond money. The grand opening in August 2012 featured local bigwigs and politicians, and a presentation from the school honor guard.

Caty Presas-Garcia, a Brownsville ISD trustee who was once Salinas’ administrative assistant at the school, is a firm believer in the power of BAC, and wants to see the model grow. “When I worked with Col. Salinas, it was really an eye-opener,” she says. “By the time they’re in middle school, they’re starting to do drugs, their hormones are changing, they’re developing. So when do you structure them?” Even younger, she says—it should start in elementary school.

She concedes she probably feels more strongly than most because she comes from a military family. Her father served in Vietnam and her siblings were in the Air Force. Spreading the boot camp model would mean good jobs for returning veterans, she says, and more students would benefit. “If people were to really embrace it, I think we’d have less crime in our communities,” she says.

“Personally, I’d love to put the Marines or SEALs in our schools so we can start developing future students that want to go into the service,” she says. She mentions the Border Patrol and customs as well. “We’re on the border, why not? Our students will have such great opportunities.”

Carmen Rocco, a pediatrician with her own clinic a few miles from the boot camp, argues that the BAC is indoctrinating Brownsville’s school kids.

“The most common way out when you see kids graduating from high school—like any other impoverished community—it’s the Army, the Navy,” she says. “Get ’em to believe the best thing to happen to them is a pair of Army boots, and I have a problem with that. Give them a stethoscope. What’s wrong with that?”

She worries that boot camp is too blunt an instrument for students with complex problems, and their stays too short to be much of a solution. Military discipline isn’t the answer, she says, when students with mental-health issues need psychiatrists, and there’s only one in town, with a wait list months long. “I think there’s a lot more creative and effective ways of doing it,” Rocco says.

Marsha Griffin, another pediatrician, whose job entails signing off on students’ medical releases when they’re assigned to BAC, says she’s heard of kids sent to BAC for minor infractions—things that she never would’ve been kicked out of school for when she was a kid. “We didn’t grow up in a culture of zero-tolerance. We had mentors and parents and teachers that really tried to help children grow into adulthood,” she says. “What happened in the ’60s? Kids were talking back and dressing different, and we didn’t haul them off to prison camp.”

She frets about the school district’s role in criminalizing students, and that this particular experiment in alternative education is being visited upon a vulnerable community that’s unlikely to push back. Parents in the U.S. illegally aren’t likely to lodge a complaint with the higher-ups if they don’t want their kid sent to boot camp. (Since 2005, the state and the district have received just one formal complaint about BAC.)

Some critics in the community wonder if the boot camp is continuing an ugly local tradition. A 2010 study by the children’s advocacy group Texas Appleseed pegged Brownsville ISD as a leading issuer of misdemeanor tickets and expulsions—its 176 expulsions were ninth-highest in the state in 2007-2008. (After instituting rules to limit its ticketing, Brownsville ISD issued far fewer citations beginning in 2009, Texas Appleseed noted.)

The Texas Appleseed study has sparked a statewide conversation about the consequences of criminalizing student misbehavior in school. It has become an epidemic in Texas: misbehavior that once resulted in suspensions now leads to criminal charges. Texas Appleseed’s study also found that Texas schools ticket African-American and Latino students for misbehavior, including swearing, far more often than white students, saddling them with juvenile records and acclimating them to life on the wrong side of the law.

BAC’s all-Latino student body isn’t so remarkable in a 98-percent Latino district. Consider, though, that there are troubled and troublesome kids all over Texas, but it’s mostly the ones in Brownsville—one of the poorest cities in the country—who get boot camp. Misbehaving kids from Austin, Houston and Highland Park don’t wear battle-dress uniforms to school or have a drill sergeant follow them into the bathroom for “head breaks.” Most of BAC’s students come from schools in the poorest parts of town, where the military and Border Patrol recruit heavily.

“This is a community that’s become militarized in an extraordinary way,” says Mike Seifert, Griffin’s husband and coordinator of the Rio Grande Valley Equal Voice Network, which includes 11 community groups. School officials aren’t inclined to talk about the Border Patrol as anything but a career opportunity, but the helicopter flyovers, the border wall cutting off the town, and the green and white trucks parked alongside it—Seifert says they’ve all hardened the city in the past few years. Throw in a boot camp at the school district and the town looks even rougher. “At the end of the day,” he asks, “is it really about brutalizing people?”

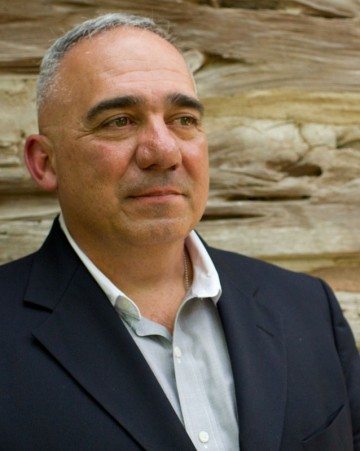

Brownsville may have become militarized, but BAC’s principal, Carlos Guerra, is not a military man. He stops short of Presas-Garcia’s boosterism, but still says there’s a big difference between his school and real military training. “We’re not a military boot camp. We’re not a military school,” he says. “We’re trying to discipline them, to teach them to make good choices. Not prepare them for war.”

Guerra joined BAC in August, in time to dedicate the new school. A former superintendent at tiny San Perlita ISD a few miles north along the coast, he has gray hair and a white mustache, and the warm but professional air of an anchor on the evening news. He happened into the job by accident, he says. “According to the district, it was in the best interest of the district for me to come here.”

He says the military format helps simplify things for students. At a regular school, even a trip to the bathroom presents the options of taking the long or the short way, or skipping out of school altogether. With a drill instructor on kids’ heels, the DI’s way becomes the only option. “That relieves a lot of stress for them,” Guerra says. “You’ve made a lot of decisions for them that they really don’t want to make or may be ill-equipped to make.”

Guerra agrees with Rocco that kids need more counselors and support. Some kids, he says, are referred to drug rehab or outside counseling. “Many of them come from broken homes, and they’re dealing with issues that you and I can’t even fathom. To spend five to 10 minutes with a counselor does not do them justice.” The district just hopes that six or nine weeks of boot-camp discipline are enough to help its kids.

Still, it’s expensive to keep the school running. Constructing the school cost plenty, but then there’s the extra staff—enough teachers to maintain a 15-to-1 student-teacher ratio, plus 12 drill instructors, eight special-education teachers and other aides. Brownsville ISD is spending $2.7 million of its supplemental state funding on BAC, far more than any other school in the district gets. That might seem like too much money on a military-style facility that’s unlike almost any other school in Texas. But Guerra argues that the district is trying to turn lives around. “What goes into the building, what goes into the uniforms—you change one kid, it’s worth the expense. This building has paid for itself many times.”

But even Guerra wonders whether some of his kids, sent to boot camp for minor offenses, should have been removed from their regular schools. “I have had some referrals where I thought, ‘Really?’” he says. “Certainly some of these referrals are questionable, and I feel that they could have been handled in a different manner.” But he doesn’t get to pick his students, he says—he just tries his best with the ones he has.

Annabel Velez’ 10th-grade son was sent to BAC this spring, an assignment he received, along with criminal probation, for chronic truancy. Driving her son to BAC in the morning wasn’t a problem, she says, but it was tough for her to get away from work in the afternoon every day to pick him up.

Guerra and Salinas agree the program is meant to impact parents too. Salinas says he wanted parents to pick up and drop off their students every day, to ensure extra involvement in their child’s school life.

“You are not punishing the student,” Velez says. “You are punishing the parent.”

She recalls their first visit to BAC, before her son’s first day. A drill instructor noticed her son’s shirt hanging out and yelled at him to tuck it in. It shocked Velez to see a stranger come down so hard on her son. But modeling that discipline for parents is part of the point. Velez wasn’t about to argue. “There’s nothing I could have said or done, because they’re the school, and that’s the way,” she says.

Her son liked the program. He’s still on probation and another referral to BAC will be bad for his record, so Velez is encouraged that the lessons seem to be sticking. He doesn’t need nagging to get up in the morning for school anymore, and he’s been exercising more. He got a punching bag at home, so he can work out his anger, and he even started drinking protein shakes. “Before, it was just go home and sleep. Now, he likes to go to the gym,” she says. “Plus, lately, he’s been talking about going into the Army.”

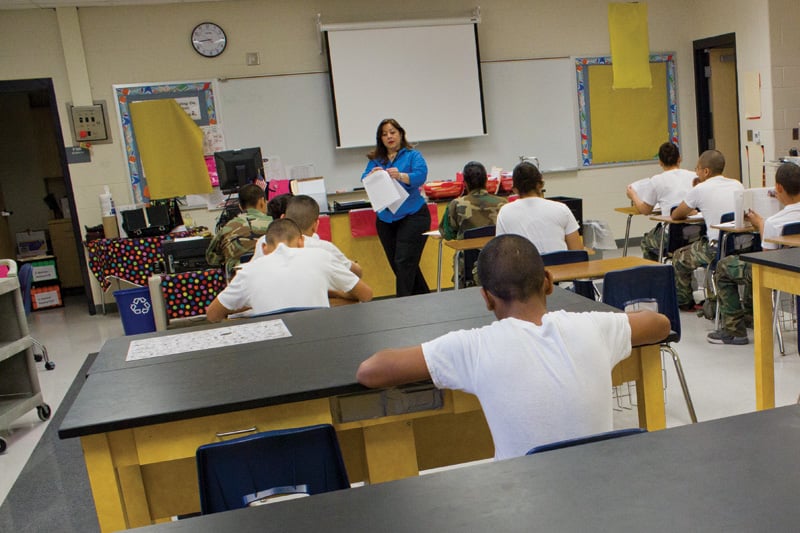

The school hallways are lined with a gray stripe of tile, and that’s where the cadets line up outside their first class. As they file in and find a spot among the desks, it starts to feel more like school than boot camp. They’re still in camouflage pants, but most have shed their uniform blouse for a white T-shirt. The teachers are dressed like teachers anywhere, smart business casual or school hoodie and jeans.

American schools are often criticized as institutional, creativity-stifling places that teach kids to stay in line. Most don’t have Drill Instructor Salinas looming beside the whiteboard, stone-faced in full camo, shaved head and goatee. This is part of the handoff of authority, though, and after a few minutes he leaves control of the middle-school classroom to reading teacher Rosie Martinez. It’s a delicate balance, and the DIs are never too far away to maintain order.

Students begin by reading. One stands a hardcover book entitled Cars on his desk, and buries his head in pages full of big type and chrome. Students must read two or three books, depending on the length of their stay, to move on from BAC. Martinez next guides her class through a lesson on social skills, talking about who has bullied other kids and why, and how they can cool off when they’re frustrated at school.

“You’re faced with this every day,” Martinez says. “Here, we tell you when to talk, when to walk, when to do anything. You go back to your home campus, you don’t have any of that.”

A few kids say they’d rather not go back at all.

“But you can’t stay here,” she tells them. “You need to move on and make better choices.”

When a student whistles—a quick double note, easy to miss, but he’s been told before not to do it—Martinez finds a drill instructor in the hallway who pulls the boy out for a few minutes of “redirection.”

“Once they enter the classroom, they belong to the teachers, but they’re still expected to comport themselves with the military discipline,” explains Gilbert Sauceda, the head drill instructor. When they’re pulled out to speak with a DI, students may talk out the problem or go out to the circle for some exercises and then return to class. If they don’t cooperate, they’re sentenced to either in-school suspension—in a separate classroom at BAC—or sent to juvenile probation. “They know that once they come to me, things can go either way,” Sauceda says.

Nearly all the DIs were in the military, but Sauceda is one of only two with combat experience. He’s a Brownsville native who served in Desert Storm, then worked in traditional public schools before learning about Salinas’ new boot camp in the 1990s. He hired on a few months after the school opened and hasn’t left. It’s a rare opportunity, he says, to keep up the military lifestyle—from the pageantry to the esprit de corps—without remaining in the service. He can go home to his family every night.

Sauceda says it’s “80 to 90 percent” like the real thing, but the drill instructors at BAC are part drill sergeant and part counselor. They talk a lot about tough love, knowing when to push and when to back off.

Principal Guerra credits the people he works with, like Sauceda, for helping the kids who come through BAC. “We can’t use a cookie-cutter approach for these kids. They all have their own personalities, their own things that set them off,” Guerra says. “A lot of these kids, what they need is a lot of encouragement.

“I’ve seen some of the most hardcore of them come in, and we talk to them, and they break down in tears. … We start getting to the main issue, their problems at home and things like that, it’s what’s bringing them here indirectly. Because of what’s going on at home, they misbehave in school.”

A little before noon, the kids march back outside to the courtyard. Most days this is the time for more exercise, but on Fridays it’s time for awards. It’s bright out, with sounds of nearby construction and a warm, humid breeze blowing in.

Cadets arrange themselves in five platoons, hands clasped behind their backs. A drill instructor faces each group. The honor guard, four students in all-black uniforms, marches in bearing flags and fake rifles. Guerra appears in a navy suit, tie-less with a light blue shirt. He calls students forward in small groups to receive awards for perfect attendance or exemplary reading. He gives the “Principal’s Award” to a girl from the honor guard who impressed him with an essay she wrote about being pulled out of class for a talk with a DI and how their conversation gave her hope she’d never felt before.

Last, Guerra calls the names of 25 cadets who step forward from the ranks dressed in white T-shirts and jeans, their dress uniforms all bagged in plastic on the ground, boots traded for sneakers. They are leaving BAC for their home campuses next week.

Because BAC takes all out-of-school suspensions, and not just expulsions, return rates are now higher than they were in Salinas’ day. One student is on his fourth tour of the year. Critics like Rocco, the pediatrician, doubt that 45 days is long enough to make a meaningful impact on a troubled kid, but Guerra notes that the time limit is set by state law. Kids stay longer only if they get in trouble again, so he says staff tries to instill motivation, self-esteem and discipline, the things they’ll need to avoid coming back. It’s a lot to expect from any school, even an extreme one like this.

That’s one of the last thoughts Guerra leaves with the outbound cadets, some lined up in formation for the last time: “Now,” he says, “begins the hard part.”