At the Mary P. Lucio Health Center one July afternoon, Esmeralda Treto gets the news she is hoping for: Treto, a 34-year-old mother of two, is pregnant with her third child. But for medical staff at the Brownsville clinic, Treto’s visit is also a chance to give the expectant mother a test for the Zika virus and educate her about the disease. On this day, the staff has its hands full. “We have another one!” a nurse shouts from the next room, as she shuttles a second pregnant woman into the room to join us. The place is bustling with patients, many of whom rarely see nurses or doctors. For public health workers on the front lines of the fight against Zika in Brownsville, where at least two babies were born with microcephaly in the last year, a single encounter with a patient can make all the difference.

Treto didn’t know she could contract Zika from a sexual partner. She didn’t know what the symptoms look like, or that only 20 percent of patients show any sign of infection at all. Though she knew the virus is transmitted by mosquitoes, she was unclear on how to protect herself.

“I thought I only had to apply [mosquito repellent] over my stomach, but now I know it has to be everywhere,” she said in Spanish.

Treto was better-informed than many in Brownsville, the seat of Cameron County. About three-quarters of pregnant women who come to the clinic don’t even know that Zika exists, much less how to avoid it, said Yvette Ortega, a nurse practitioner who works for the Cameron County Health Department. Since the rash of cases last year, pregnant women in the county have been tested for Zika each trimester. “The best defense against Zika is prevention, but that’s tricky. Our patient population is very poor, uninsured, low socio-economic status, so they’re not really concerned about something that’s not on their radar,” Ortega said. “Zika is just not on their radar.”

“I thought I only had to apply [mosquito repellent] over my stomach, but now I know it has to be everywhere.”

Educating men on Zika can be especially challenging, said Ryan Loftin, director of Maternal Fetal Medicine Services at Driscoll Health System in Corpus Christi, which opened a new clinic in Brownsville this year. “Women are far more willing to wear mosquito repellant than their husbands are to wear condoms,” he said.

Public health workers say they also contend with a kind of medical fatalism. Lo que dice Dios is how one clinic nurse described the attitude of many patients. Whatever God says.

Ever since Cameron County emerged as a hot spot for Zika in 2016, local officials have been waging a kind of scrappy rearguard action against the disease — one that has dropped off the radar as Zika fades from the news.

Brownsville and the lower Rio Grande Valley have almost perfect conditions for Zika: a year-round mosquito season, some of the worst poverty in the nation, a tattered health care system and an international border crossed daily by tens of thousands of people. Since September 2016, Cameron County has seen 37 cases of Zika, about 10 percent of the state total and a higher rate per capita than all but one other Texas county. Though the number of Zika cases in Texas has dropped significantly in 2017, more than one-quarter hail from Cameron County. As of November, all seven Texans who have acquired Zika from mosquitoes locally did so in Cameron County. The first local case was found at the Lucio clinic in November 2016.

The health care system in the Valley is so weak that public health officials say they struggle to manage a persistent infectious disease threat. Michael Seifert, a longtime community organizer in Brownsville, described the system as “scraps of paper passed around from one social worker to another, offering hints at where one might find an affordable medical procedure.” There’s a shortage of both primary care doctors and specialists. Safety-net health centers are low on funding. The only abortion clinic in the Valley is 60 miles from Brownsville.

“It’s really a crisis,” said Lisa Mitchell-Bennett, project manager at the UTHealth School of Public Health in Brownsville. “You add a sexually transmitted and mosquito-borne disease to that, how are we going to manage?”

Lo que dice Dios is how one clinic nurse described the attitude of many patients. Whatever God says.

Local officials say they’ve been managing as best they can with limited support from the state and federal governments. So far, Texas has contributed just $571,000 of its own funds to Zika prevention statewide — about half as much as Pfizer, the pharmaceutical giant. Federal agencies, primarily the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), have chipped in about $31 million, most of which expires next summer. Federal funding is already stretched thin and may be subject to devastating cuts under President Trump.

The scarcity of resources puts Brownsville in a bind: The community can’t afford a Zika outbreak, but it also can’t afford to prevent one.

So far in 2017, the number of Zika cases in Cameron County has dropped from 26 in 2016 to 11 as of early November. While experts cheer the improvement, they also warn that the drop may be only temporary and could breed a dangerous complacency.

“I’m pleasantly surprised, for now,” Texas Health Commissioner John Hellerstedt told the Observer. But, he added, “Our population is as vulnerable as they ever were. [Zika] could get started and take off.”

On a rainy mid-July afternoon, I join Lupita Sanchez on a tour of the front yards of Brownsville’s poorest. Since Zika first came to the city last winter, Sanchez, who works for the local nonprofit Proyecto Juan Diego, has led teams of volunteers in Cameron Park, a colonia on the outskirts of Brownsville. In addition to educating people about how to protect themselves from Zika, much of the work is essentially a form of spring cleaning.

As we drive around the neighborhood, she points out the homes of people she’s helped, mainly young women who are most at risk for Zika: a single mom with three kids who had 23 tires and a couple of mattresses outside her home before Sanchez helped clear them out; a new widow, who had waist-high grass in her yard until she got help trimming it.

On one street, Sanchez stops the car and points at dead tree branches piled on the sidewalk. Pieces of trash sit between them, soggy from the rain.

“That’s what could kill us,” she says, laughing.

Pools of water gather in driveways, on garbage bags and inside tires left on the curb. Mosquitoes can breed in less than an inch of water, so Sanchez’s task is to eliminate these sources.

“It’s not that people don’t want clean surroundings or don’t prioritize good health,” she says. “We know the struggles of low-income families and the decisions they have to make. And they’d prefer to pay for rent and food rather than trash pickup.”

Cameron Park is one of the poorest neighborhoods in one of the poorest cities in the United States. Sanchez, whose family is from across the border in Matamoros, Mexico, settled in Cameron Park about 20 years ago after growing up on both sides of the border. Everyone seems to know her. She’s 46 years old, with a youthful, round face and the air of a friendly town matriarch. Sanchez is proud of how her community has changed; she remembers when there were no paved roads or streetlights just two decades ago. Many homes still don’t have air conditioning; screen-less windows are left open to catch the breeze.

About 40 percent of Brownsville residents don’t have health insurance‚ twice the uninsured rate of Texas, which has the highest of all 50 states, and four times as high as the United States overall. That means medical professionals like those at the Lucio clinic often don’t have the chance to educate people on protecting themselves from Zika.

“We know the struggles of low-income families and the decisions they have to make. And they’d prefer to pay for rent and food rather than trash pickup.”

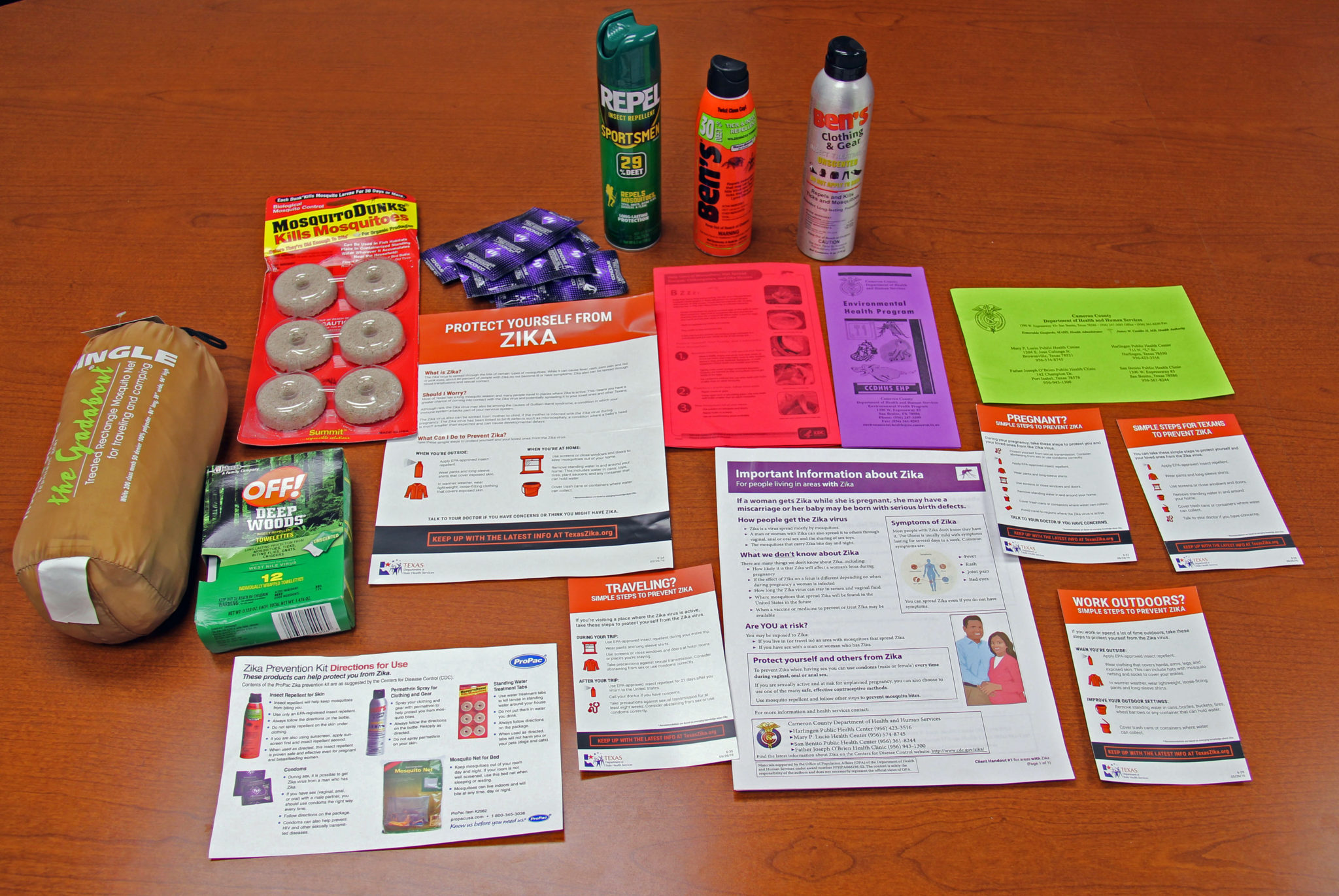

With the city strapped for resources, education falls largely to organizers like Sanchez, along with volunteers and community health workers. On the tour, Sanchez repeats the message like a mantra: Remove standing water. Wear mosquito repellent. Wear condoms. It’s meant to be a message of empowerment: You can control your health by controlling your environment.

Sometimes it sticks better than others. When Sanchez went back to check on one mother a week after she helped clean her yard, she found two inflatable swimming pools outside her home, full and uncovered, with mosquitoes floating on the surface. “I almost had a heart attack,” Sanchez laughed. “People aren’t understanding correctly.”

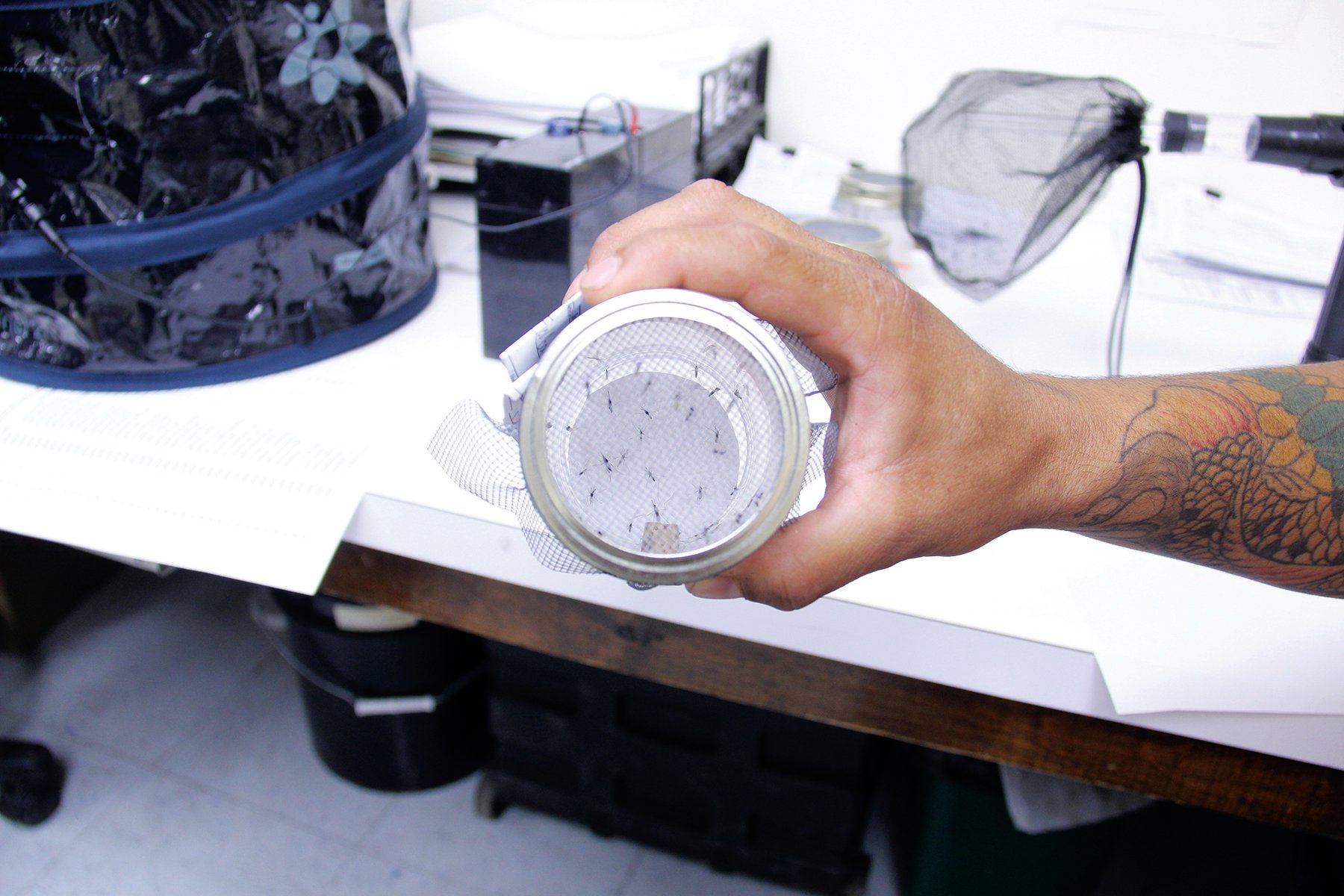

About 6 miles south of Cameron Park, and a stone’s throw from the border, the Brownsville Health Department’s mosquito lab is housed in a small back room in an annex building above the parking garage.

Mosquitoes are collected four times a week from 52 traps around the city and brought here. The health department doesn’t have enough staff to do the collections, so director Arturo “Art” Rodriguez “borrows” a few employees from the Parks and Public Works departments to help out. Every weekend, one worker gets mosquito duty. He or she comes to the office to feed sugar water to the insects and keep them alive long enough to ship to the state lab in Austin. So far, the city has sent about 75,000 jars to the Texas Department of State Health Services for testing. When I visit in July, two men are gently vacuuming mosquitoes out of mesh bags into small plastic containers to be mailed.

No mosquito has yet tested positive for Zika. But the traps provide local officials with what they say is useful information about mosquito activity. If more than five mosquitoes are found in a particular trap after 24 hours, a health department employee goes to check out the neighborhood. They empty standing water and use mosquito dunks to kill larvae in puddles. If the counts are higher, they may spray the neighborhood with insecticide.

Public health experts say there are two main elements to Zika prevention and response: monitoring humans for the disease and controlling mosquitoes. The county takes care of human surveillance, as it’s known, using funds allocated by the state. The city is responsible for mosquito control within Brownsville’s limits, but it doesn’t receive any direct funding from the state or feds.

Rodriguez describes the situation as a kind of unfunded mandate. “Public perception is that Washington and Austin have earmarked millions of dollars for Zika, but we’re not seeing any of it,” he said.

When I ask Hellerstedt, the Texas health commissioner, about the criticism, he invokes the principle of local control. In Texas, local health departments are responsible for managing disease response on their turf. “They can come talk to us if it can’t be met with their resources,” he said.

But that means Brownsville, which has spent nearly $500,000 of its own funds on the Zika response so far, isn’t getting help until it shows it’s near a crisis. In September, the state agreed to help the city with mosquito spraying for a few weeks, after the traps showed dramatic spikes in mosquito counts. The assistance was appreciated, but short-term. Rodriguez worries that they won’t get that kind of help again.

Figuring out how the state allocates federal funding to local health departments is itself a challenge. The Department of State Health Services provided a spreadsheet to the Observer that shows how the agency divvied up $11 million in CDC funding for Zika response among 18 local departments. In general, areas with more Zika cases, such as Cameron County, were to receive proportionally more money. However, the initial calculation was based on a count of Zika cases that was a third less than the actual total. Asked about the discrepancy, the agency said it was an “oversight,” but in the end “there were adjustments made” before final grants were distributed. The agency couldn’t provide any documentation of what those adjustments were, though Cameron County did receive more money than initially proposed.

“Public perception is that Washington and Austin have earmarked millions of dollars for Zika, but we’re not seeing any of it.”

When we met in October, Rodriguez asked if I knew why Cameron County received funding and Brownsville didn’t. “I haven’t been able to get them to give me the answer,” Rodriguez said. “I’ve been calling” — he lowers his voice and laughs — “anyone who will listen to me.”

Rodriguez said he “wasn’t at the table” when the state health department decided how to award Zika funding. But he thinks that the poorest, most vulnerable communities are simply not getting enough support. He sketches something for me on a piece of paper: three people of different heights standing behind a fence, trying to watch a baseball game on the other side. Only if they’re given steps proportional to their height to stand on can all three see the game unobstructed. He points to the shortest kid, who can’t see over the fence when given an equal step to stand on. “That’s us.”

In May, almost six months after the first local case was found in Brownsville, Hellerstedt and Governor Greg Abbott hosted a Zika “call to action” in the city for local officials. It didn’t sit well with Rodriguez. “I realized there was a blind spot between the message [Abbott] was saying and what we’re already doing,” he said. “Why wasn’t anyone keeping the upper echelons of the government up to date on how much we’re doing at the local level? … I mean, we’re working our tail off and he’s coming to say ‘call to action.’ Really, dude?”

Rodriguez says he’s looking at options for 2018 to try to become “equal partners in the funding,” starting with asking state officials to come to Brownsville this winter to discuss plans for next year’s Zika response. “Since I wasn’t invited to their table,” he said, “I’m inviting them to mine.”

Both local and state officials are worried that federal funding will soon dry up. Public health funding, regularly on the chopping block, is facing a greater threat under the Trump administration, which in May proposed cutting the CDC’s budget by 17 percent.

“If there’s local transmission next summer, [that money] likely won’t be here,” said Imelda Garcia, head of infectious disease prevention at the Department of State Health Services. “How do we set up infrastructure knowing there will be ongoing transmission?” That uncertainty means the state isn’t planning on starting a new funding contract with Brownsville or other local health departments soon.

At the same time, the state has hampered Brownsville’s efforts to fund itself. In 2010, the Brownsville City Council passed an ordinance, led by Rodriguez, imposing a $1 fee for plastic bags at stores, revenue that the city then tapped, in part, to pay for Zika awareness. But last year, Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton sued the city, calling the ordinance an “illegal sales tax,” and the city responded by ending it early this year.

Funding for Zika outreach got so tight in 2017 that Rodriguez turned to his counterpart in Matamoros, Mexico, for help. He and José Antonio Alfaro Caballero, the health director in Matamoros, put together a bilingual messaging campaign urging people to eliminate mosquito breeding sources in their homes. Matamoros designed the brochures, and Brownsville planned to print them in the summer. But the project was put on hold for months while Rodriguez scrounged up a $10,000 grant from the state’s Office of Border Health. He’s now hoping it’s enough to print the brochures, at least for a few months.

When CDC officials came to Brownsville in July, Cameron County health administrator Esmeralda “Esmer” Guajardo wanted to make sure they understood the international nature of the Zika fight. She piled the delegation into a van and had her deputies give the federal officials a tour of the border near Cameron County. They drove along the border wall as it snaked through backyards in Los Indios, just west of Brownsville. At an international bridge that connects Matamoros and Brownsville, they saw the line of cars waiting to cross and heard that the sister cities see about 1 million crossings a month.

When I meet Guajardo at her office in San Benito this summer, she’s seated in front of a small sign that reads “Why didn’t Noah swat the two mosquitoes?” She tells me that one of her biggest frustrations is having to classify Zika cases as either “locally acquired” or “travel-related,” a distinction that’s frequently blurred in the Valley. People live in Brownsville and go grocery shopping in Matamoros. They live in Matamoros and work in Brownsville. They cross the border to visit family and to see a doctor. If someone catches Zika in Mexico, where it’s more prevalent, and returns to Brownsville, they can spread it to others through sex, or start a new chain of mosquito transmission if they’re bitten in Texas.

“I’ve been calling” — he lowers his voice and laughs — “anyone who will listen to me.”

“When you talk to a person who’s tested positive and ask questions about where they traveled, anyone outside the border will tell you the specific time frame and where they traveled with Zika. Here, if you ask when someone has been in Mexico in the last two weeks, they’ll tell you every single day,” Guajardo said. “How are you supposed to figure out if it’s a travel or local case?”

The distinction matters because a local case is considered a bigger threat, necessitating a more robust and expensive response. Because they can’t be sure, county officials treat almost every case as if it were locally acquired. That means talking to the patient, testing immediate family members, doing door-to-door outreach. It means more time and money, both of which are in limited supply.

Guajardo said CDC has taken a few steps to confront the international nature of Zika in the Valley. This spring, the agency dispatched an employee to the Cameron County Health Department and one to the city of Brownsville to serve as liaisons between the locals and the feds. Guajardo and other border officials also convinced the Texas Legislature to create a task force to advise Hellerstedt on border health concerns; it meets for the first time in December. But locals say the response from higher-ups can be too little, too late. The scarcity and uncertainty of funding makes it difficult to plan a sustainable response long term, one that can continue after public attention has waned.

Meanwhile, Rodriguez said coordination with Mexico so far has been mostly informal and local. “This isn’t like other parts of Texas, where they know other taxpaying entities are around protecting them,” he said. “I know that across the river is another country, and my only information of what’s happening south of the border is by me picking up the phone and calling a different government and saying, ‘Are you willing to tell me what you’re doing?’”

But it seems that Rodriguez is the only official who is talking to his Mexican counterparts.

Communication with Mexico “could always be better,” said Hellerstedt, but he said Texas doesn’t have much contact with Mexico because “we don’t need it.” It’s a task better left to the local health departments, he said.

“We don’t know what’s happening in Mexico,” confirmed James Castillo, a physician and county official tasked with providing medical expertise to the county health department. Communication within Texas and the United States is more important, he said. “If the number of Zika cases in Mexico starts dropping, that will probably look good for everyone. But right now I’m not really sure what’s happening in Mexico.”

That’s troubling because the number of confirmed cases of Zika in nearby Tamaulipas has spiked this year. As of late October, there were 560 cases, almost quadruple the number of cases in 2015 and 2016 combined.

In October, Cameron County announced a new locally transmitted Zika case, this time in Laguna Heights, 20 miles northeast of Brownsville. The case offered an unwelcome reminder that Zika and other infectious diseases will be here for a long time.

Mosquito-borne illnesses on the Texas-Mexico border tend not to go away. Instead, they re-emerge in waves. “We can learn from closely related viruses, like dengue and yellow fever, which are carried by the same mosquito as Zika,” said Pei-Yong Shi, a professor at the University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston and a leading Zika researcher. “For example, dengue in an endemic area continues to cause sporadic or epidemic situations.” In the summer of 2005, Brownsville had a dengue outbreak that was tied to a much larger epidemic in Matamoros. Cases continued at a low level until a new wave emerged in Brownsville in 2013. “Many factors contribute to the up and down of these outbreaks,” said Shi. To minimize them, constant mosquito control and surveillance is critical.

“It’s really easy to cut funding for local health departments or public health in general because you don’t see its value on its face.”

Shi said that what’s needed in the long term is a Zika vaccine. He’s involved in developing one that was recently found to protect mouse fetuses against Zika infection, but he says approval for humans is at least a year away. Even then, it’s unclear how widely available such a vaccine would be. A pricey vaccine would do little for Brownsville, where so many people lack insurance.

Already, development of one Zika vaccine was put on hold following funding cuts from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

“It’s really easy to cut funding for local health departments or public health in general because you don’t see its value on its face,” Castillo said. “Along the border region specifically, it’s these kinds of illnesses with slow-moving transmissions like influenza, Zika, dengue, that move into our communities first. If we didn’t have a good response along the border, they’d just keep going.”

Guajardo is dreading the day funding is cut off. “The most frustrating part is that I have to send a press release about this new case because people need to remember Zika is still here,” she said in October. The county’s Zika contract goes to the middle of next year. Then what? “In this political landscape, there’s no telling what funding will look like on the border,” she said. “But we can’t let our guard down. Today it might be Zika, tomorrow it’ll be something else.”