Bordering on Empty

The Rio Grande is one of the most endangered rivers in the world. The Rio Grande Valley is one of the fastest-growing regions in the nation. Can South Texas weather a hotter, drier future?

[txo_vimeo_embed id=”284812153″ align=”giant” caption=”Erik Olsen/Quartz” autoplay=”onview”]

by Naveena Sadasivam

August 21, 2018

Three years into one of the most extreme droughts in Texas history, Raymondville City Manager Eleazar “Yogi” Garcia was facing a worst-case scenario. It was February 2013, still technically winter in Raymondville, a humble border city of 11,000 about 30 miles north of the Rio Grande, and the two giant border reservoirs — Amistad and Falcon — were only about a third full. For months, farmers in the Rio Grande Valley had been calling elected officials in Texas and Washington, D.C., demanding that they force Mexico to release water it owed Texas under treaty obligations. Now, the consequences of a parched river were coming to bear on little Raymondville: Garcia had just received a letter from the city’s water provider stating that it could run out of water in 60 days. It was the first time in the 22 years Garcia had been city manager that he was faced with the prospect of empty taps and tubs.

The situation required drastic action. Garcia switched the city from stage 1 voluntary conservation to stage 3 for severe water shortage conditions, shutting down fountains and ornamental ponds, emptying swimming pools and limiting when residents could water their lawns. But conservation alone wasn’t going to save the city. On paper, Raymondville had plenty of Rio Grande water to serve its population; the real trouble lay in moving it north through 56 miles of canals and pipes to the city’s water treatment plant.

“It didn’t matter what kind of rights I had at the river,” Garcia said. “I couldn’t get the water here.”

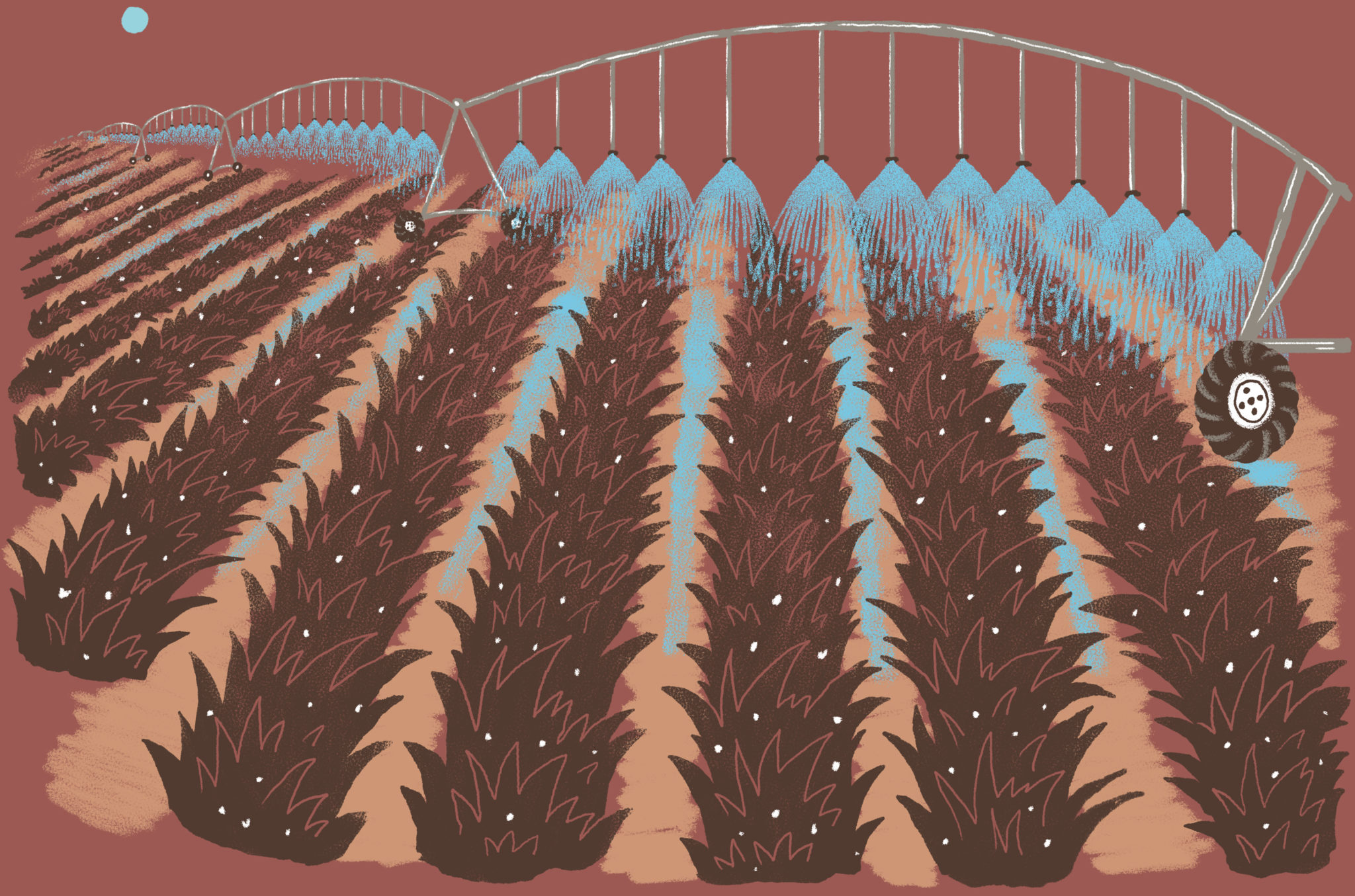

Like most cities in the Valley, Raymondville buys water from one of about two dozen irrigation districts, which hold the rights to pump and sell water from the Rio Grande. The districts were created in the early 1900s, when farmers began experimenting with growing rice, sugarcane and citrus in the semi-tropical Brownsville area, southeast of Raymondville, where the Rio Grande empties into the Gulf of Mexico. Over time, the farmers dug hundreds of miles of earthen canals to move the river’s bounty inland. The canals leaked from the beginning. Though the districts have spent millions upgrading the system — lining some canals and replacing others with pipelines — the canals lose, on average, 41 percent of the water to leakage and evaporation.

In Raymondville’s case, Delta Lake Irrigation District, the largest district in the Valley, is contractually responsible for delivering about 5,670 acre-feet — enough water to fill about 2,800 Olympic swimming pools — to the city every year. In wet times, the system works well enough. When the river is full, farmers in the Valley can take full advantage of their rights, diverting huge quantities of water to irrigate their fields. The municipal water, which is a small fraction of the total, hitches a ride like a drop in a stream, buffered from being lost to the ground or the air by the enormous quantity of agricultural water. But as Garcia discovered in 2013, during times of drought, there sometimes isn’t enough “push water” — as the buffer water is called — to make deliveries to Raymondville. Imagine Delta Lake’s canals as long, leaky sieves. As water courses along, the ground sponges away its share and evaporation takes its cut; by the time a delivery of water reaches its destination, about a third has been lost. The region’s labyrinthine network of leaky canals was simply not designed to serve the 1.3 million people living in the Rio Grande Valley today.

Faced with the prospect of Raymondville running dry, Garcia tapped into the city’s meager coffers. For the first time in Raymondville history, the city bought extra water from another irrigation district: an additional 1,000 acre-feet for $37,500, to be used as push water, a sort of sacrificial tranche, just enough to get the rest of the delivery through the canals to Raymondville. But a week before Day Zero, the skies opened up and the river filled. The push water stayed in the river.

Garcia is now trying to make sure there’s never another near miss in Raymondville. The city has a $1.8 million grant from the state to help build a reverse osmosis plant that treats groundwater, and development is underway. Once it’s up and running in a few years, the drinking water from the plant will be twice as expensive as the Rio Grande water, but Garcia says Raymondville doesn’t have a choice. “When you’re out of water, you’re out of water,” he said. “It’s pretty rough.”

The Rio Grande basin provides drinking water to 6 million people and irrigates 2 million acres in the United States and Mexico. As the region gets drier and hotter because of climate change, the Rio Grande is shriveling. According to a 2013 federal study, even before accounting for climate change the Rio Grande Valley is expected to run a “staggering” water supply shortage of almost 600,000 acre-feet in 2060. More than a third of the region’s need would be unmet. Scientists predict that even if greenhouse gas emissions are drastically cut, the effects of climate change will add an additional 86,000 acre-feet to the anticipated shortage.

Scarcity is already beginning to expose deep inefficiencies in the Valley’s water infrastructure. It’s also pitting farmers against cities. Because cities are guaranteed first dibs on the Rio Grande, shortages are first borne by farmers. And as the Valley rapidly urbanizes, developers are gobbling up farmland and agricultural water rights, heightening conflict between the two interests. Growing stress on the Rio Grande also adds more uncertainty to the relationship between the United States and Mexico, which are bound legally and hydrologically to share the desert river. The lower stretches of the Rio Grande are particularly dependent on Mexico releasing water from tributaries in the rainy highlands of northwestern Mexico.

Raymondville wasn’t the only community with a near miss in 2013. Municipalities in the Valley with a combined population of more than 800,000 people received similar letters from irrigation districts informing them that they were close to running out of water. Lyford, a town of 2,600 people 5 miles south of Raymondville, was in an even more serious predicament; the town couldn’t afford push water. A 2015 study found that five irrigation districts serving about 340,000 acres of farmland in the Valley were at “the highest risk of needing push water” during a drought and noted that “there are likely to be significant public health and economic impacts” if cities can’t secure water for their residents. Given that some 35 percent of Valley residents live below the poverty level (compared to about 16 percent statewide), such shortages could be catastrophic.

“We’ve been lucky so far,” said Guy Fipps, a professor at Texas A&M University, “but if a district has no water, then the city won’t get any water.”

[txo_vimeo_embed id=”284812169″ align=”giant” caption=”Erik Olsen/Quartz” autoplay=”onview”]

When Spanish conquistador Juan de Oñate crossed the Rio Bravo del Norte, as the Spanish called the Rio Grande, in 1598 at El Paso del Norte, the river was untamed. Flowing from the cradle of the Sangre de Cristo Mountains in present-day southeastern Colorado, the river was a striking feature in the Chihuahuan Desert. Brash and braided, it tumbled from the mountains down a 1,900-mile path, undulating north-south down the middle of what is now New Mexico and then making its turn to the southeast at El Paso, crashing through the imposing canyons of Big Bend and beyond, before leveling out in South Texas, gathering itself into a wide stream, once lined with ancient cypress trees, and emptying into the Gulf of Mexico at Boca Chica. When the river flooded, it swelled miles inland.

Over the next few centuries, the river was the site of numerous battles and became the locus of the U.S.-Mexico border, which was drawn and redrawn. Meanwhile, the population in the Rio Grande corridor grew. Farming and ranching communities put down roots along the river and, beginning in the early 1900s, both the United States and Mexico began building dams on the main stem of the river, as well as its tributaries. The cypress trees were cut down to build wharves at the Port of Brownsville and struggled to grow back after the dams interrupted the natural flood cycle.

Today, the once mighty Rio Grande is a pitiful sight. The river nourishes millions of acres of land, supports industrial activities, provides a lifeline for booming urban populations, and is a receptacle for waste from manufacturing plants and border cities — but it can’t do it all. There are more claims to the river’s water than there is water in the river. By the time the Rio Grande reaches El Paso, it’s down to a trickle. For the next 216 miles, between Fort Quitman and Presidio, it often runs completely dry. Some have taken to calling the river “El Sewer Grande.” In 2001, for the first time, the river stopped flowing before it reached the Gulf.

The river’s saving grace is the Rio Conchos, a major tributary in Mexico that joins the Rio Grande near Presidio, bringing it back to life. Then, about 300 miles downstream, the clear-running Pecos and Devils rivers pour into Lake Amistad. The water held in Falcon Lake and Amistad is apportioned between Mexico and the United States by a 1944 treaty; the United States controls a little less than 60 percent. In essence, every drop of water is accounted for and negotiated over.

Climate change is one major reason the region is at risk of a water-scarce future. Snowmelt that feeds the river’s headwaters in the Colorado mountains has decreased by 25 percent since 1950. With temperatures rising, researchers project that by 2070 evaporation rates in the lower Rio Grande will increase by 4 to 10 percent. Scientists also project that as the population in the Rio Grande Valley continues to skyrocket, the pressures on the river will become untenable. A 2013 study by the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation found that under extreme climate scenarios, the region will be short 411,000 acre-feet in 2060, a whopping 40 percent deficit. In that case, inland cities may not have a reliable way to move water from the river to their treatment plants.

The farmers in the Valley are well aware of this reality. When the situation gets dire, farming is first on the cutting board. In the rest of Texas, surface water rights are managed according to the principle of “first in time, first in right” — those with the oldest water rights receive top priority. In times of shortage, the newest rights-holders are cut off first. Below Falcon and Amistad dams, water is divvied up among farmers only after the cities’ needs are met.

But that’s not the most direct threat to the agricultural industry. As urban demand grows, cities are developing farmland and banking the water rights that come with the property. This diminishes farmers’ political clout and increases the likelihood of their greatest fear coming true: a wholesale takeover of the irrigation districts by cities.

The situation is putting enormous pressure on farmers and irrigation managers to conserve water and make improvements to wasteful infrastructure. As operations manager of the Delta Lake Irrigation District, David Lozano is in charge of keeping 505 miles of canals and pipes in working order — and leading the effort to modernize the district’s infrastructure to try to save every drop of water he can.

[txo_vimeo_embed id=”284812182″ align=”giant” caption=”Erik Olsen/Quartz” autoplay=”onview”]

On a spring day, Lozano has agreed to show me around the district. As we pull up to one of the district’s reservoirs, his iPhone buzzes again. Since we met earlier, he’s been taking calls almost nonstop from farmers, contractors and city officials.

This time it’s Lozano’s assistant, with yet another problem. A homeowner is upset that a busted pipe has been flooding her yard. “There’s a lot of water,” the assistant says. “She wants to know when y’all are going to fix it. … She said she’ll file charges.”

Lozano explains that the pipeline near the woman’s house is a defunct part of a larger network that irrigates four farms, and he can’t cut off the flow when the crops are being watered.

“I can’t have the possibility of losing even $5,000 compared to her grass,” says Lozano. “I understand that it’s irritable or frustrating to her that it’s there, but it’s going to be worse if the farmers say, ‘You’re costing me a lot of money.’”

The call is another reminder of the challenges of managing an intricate system of canals, pipes and gates built almost a century ago in a region seeing rapid development. The busted pipe used to serve a farm where the woman’s house now stands.

Lozano oversees a pumping station on the river that move millions of gallons of water 34 miles along an 80-foot-wide earthen canal to a 2,200-acre reservoir in the northern half of the district. It takes 26 hours for water pumped from the river to reach the reservoir, and by the time the deliveries reach their final destinations, about a third has been lost.

From the reservoir, lift stations push the water uphill through a network of ever-smaller canals and pipelines that deliver it to growers. In total, the district has about 300 miles of pipelines, 205 miles of canals, 47 lift stations and 38 gates. Four “canal riders” spend all day driving from one part of the district to the next, checking for leaks as well as opening and closing the network of gates that direct the water. Every day pipelines break, canal walls collapse, meters fail and people steal bronze valves to sell at the salvage yard.

It’s an exhausting, never-ending game of whack-a-mole. In part, the system struggles to keep up for the simple reason that it was built more than 80 years ago, when farmers grew an entirely different set of crops than their successors do today. Plus, the canal systems were built to deliver large amounts of water. With farmers modernizing their operations and installing drip irrigation systems, they need smaller amounts delivered over longer periods of time, a challenge for canal operators trying to manage a leaky and inefficient system. Further, the canals are increasingly being used to deliver water to ever-growing cities, stretching them beyond their intended purpose.

Yet the irrigation canals remain the only system to support the region’s $1.1-billion agriculture industry and its growing urban population. In an attempt to reduce water waste, irrigation districts have been digging up old canals and laying pipelines in their stead. Delta Lake, for instance, recently spent $8 million converting 18 miles of open canals to pipelines. The project saves the district about 6,000 acre-feet annually — about how much Raymondville uses. But Lozano is most proud of the three electronic gates the district installed last year.

Typically, when a farmer requests water, a canal rider has to manually open a series of rusty gates to direct water to the farm. There’s an art to the releases. Veteran canal riders know how many rounds to turn each wheel to release roughly the amount of water the farmer has requested. When the farmer is done irrigating, sometimes in the middle of the night, a canal rider has to drive back out to the gate and close it. If a rider misses a midnight call, the gate may not get shut till the next morning, by which time excess water has been sent through the canals.

The electronic gates are revolutionary. They’re hooked up to an app controlled by the canal riders, and with the press of a button the gates can be opened and closed remotely, programmed to allow precise quantities through.

Lozano would like to make all 38 gates in his district electronic, but the cost is prohibitive — around $200,000 for each gate. About a fifth of the district’s $3.6 million budget is consumed by constant repairs, and it also faces the same challenge confronting many water purveyors in an age of scarcity and conservation: Delta Lake sells water, and if there’s less water to sell, there’s less money coming in. Still, those who control water control the Valley, and no matter how efficient the irrigation districts get, the reality that cities are moving in on the river is hard to ignore.

[txo_vimeo_embed id=”284812219″ align=”giant” caption=”Erik Olsen/Quartz” autoplay=”onview”]

For as long as McAllen Mayor Jim Darling can remember, his city has been at odds with its water suppliers. Soon after he was sworn in as city attorney in 1978, Darling began plotting with other city officials to take over the Hidalgo County Water Improvement District 3 (HCWID3), one of McAllen’s three suppliers. They came up with what seemed like a winning plan, a hostile takeover of sorts: They would fill the five-member district board with friendly candidates, who would then vote to dissolve the district and hand the infrastructure — the pumps, pipes and canals — over to McAllen.

One of the people Darling endorsed for the board was Othal Brand Jr. Brand was born and raised in McAllen, and his family is well-known in the Valley. His father, Othal Brand Sr., was the mayor of McAllen from 1977 to 1997 and a controversial figure, known both for laying the foundation for the city’s growth and for his abrasive governing style. He infamously brandished a pistol at farmworkers and union organizers during a rash of farmworker protests that broke out in the Valley in 1975. For better or worse, Brand Jr. and his family’s legacy are inextricably linked with the growth of the city.

Darling recalls meeting with Brand Jr. in 2003 and asking him to run for a seat on the board. At the time, the district was mismanaged, Darling believed, and the city, which was the district’s main customer, would do a better job of running it. To appease the other customers — the farmers outside the city — McAllen would put their irrigation rights in a trust and ensure that they would always receive their fair share.

Brand Jr. won the water district board election in 2003, but after he took office he refused to support the district’s dissolution. He went on to become general manager of HCWID3, responsible for its day-to-day operations and protecting it from McAllen. When McAllen’s lawsuits failed to break the district, the city tried to take it over by legislative fiat. Since 2007, Valley lawmakers have pushed legislation at the Texas Capitol to allow the city to take over; in 2011, a bill made it as far as Governor Rick Perry’s desk. He vetoed the legislation, saying it was hostile to agricultural interests, an important constituency in Republican politics.

Hidalgo County Water Improvement District 3 was created in 1921, just 10 years after the incorporation of McAllen. The city’s population was about 6,000 at the time, and most residents worked farming cotton, alfalfa, citrus and figs. But over the next 90 years, the population grew steadily, helped along by the discovery of oil in Reynosa (McAllen’s sister city in Mexico), the building of an international bridge between the two cities and the trade that followed NAFTA in 1994. Slowly, the city and the surrounding area transformed from a predominantly agricultural economy to a trade hub. Today, HCWID3 serves fewer than a dozen farmers, and the vast majority of its revenue comes from a contract with McAllen worth about $1.3 million a year.

The Valley now is about 90 percent Hispanic and has voted solidly Democratic for decades. In the 2016 presidential election, about two-thirds of voters in the Valley picked Hillary Clinton over Donald Trump. Most of the local elected officials are Hispanic. But in stark contrast, more than two-thirds of all farmland in the region is operated by white farmers.

[txo_vimeo_embed id=”284812190″ align=”giant” caption=”Erik Olsen/Quartz” autoplay=”onview”]

Darling says McAllen will never give up its quest to take over the water district — it can’t afford to. As McAllen grows, its thirst has become insatiable and during times of scarcity the leaky pipes and canals lose precious water. City leaders are willing to spend money to fix the district’s canals, but only once they control the district. Overall, he says, it would be easier and more cost-efficient if the city had the authority to manage its entire water supply system, from river to tap.

“We want to control our own destiny,” said Darling. “Why wouldn’t you take over when you’re 95 percent customer and that’s your primary supplier of your product? Just that basic fact is reason enough that we should take it over.”

But Brand Jr. is a formidable political operator. During the legislative battles from 2011 to 2015, he mobilized farmers from the Valley and flew them to Austin to testify at the Texas Legislature. He hired lobbyists and threatened to increase the water rate for the city if it didn’t back down. The city fought back, and showed a willingness to play dirty, canceling its contract with the district and forcing the district into debt.

Brand says McAllen’s tactics are the result of Darling’s desire for “kingdom building” — a reckless lust for growth at any cost. The mayor is a relentless promoter of McAllen and spends much of his time recruiting businesses, working on quality-of-life issues and pushing back on media depictions of the border as dangerous and poverty-stricken. But the boosterism comes at a cost to the agricultural economy. In Brand’s estimation, McAllen covets control of the water because it eases the way for development.

Brand laughs at the notion that the irrigation system can be run more cheaply and efficiently. HCWID3 charges McAllen just 29 cents to move every 1,000 gallons of water — a price Brand considers a bargain, particularly when the city then marks it up to $1.35 or more for its residents.

“You find me anything in the world — ball bearings, frozen meat — that weighs 8,300 pounds and see if you can get it lifted 35 feet and carried 4.5 miles for 29 cents,” Brand said. “There’s nothing I know of on the face of the Earth that you can get it at that cost.”

Brand also doesn’t put much stock in McAllen’s assurances. If the city were to dissolve the district, farmers would likely lose protections guaranteeing they would receive water on time at a reasonable price, he said. Though McAllen has said it would protect the irrigators’ water rights by placing it in a trust, Brand worries that during a bad drought, farmers would be at the city’s mercy. For instance, Brand claims, at one point McAllen made annual delivery promises based on the amount of water available during a wet year, failing to account for droughts, which are a fact of life in South Texas.

“They came at it absolutely mindless about what farming is,” Brand said. “As a rule, cities are mindless. They know nothing about farming.”

Farmers across the Valley follow the McAllen-HCWID3 fight closely. They worry a takeover could create a domino effect, encouraging Brownsville or Harlingen or Edinburg to move in one of the irrigation districts that serves them. Unchecked development is driving up the value of farmland, creating powerful incentives for land-poor farmers to cash out. According to a 2007 law passed by the Texas Legislature, when farmland is sold to a developer in the Valley, the municipal water supplier in the area can compel the irrigation district to sell the water rights to the supplier — usually a city — at no more than 68 percent of the market value, converting the water use from agriculture to urban. The irrigation districts say this discount is unfair, affects their bottom line and hastens development. In any case, because the law gives higher priority to municipal water rights, the transaction has the effect of reserving more and more water for cities during times of drought.

Macarena Ortiz, a water lawyer in the Valley who represents irrigation districts, said some districts “believe they have an unlawful takings claim,” referring to the notion that regulations on water rights constitute a government seizure of private property. “They’re obligated to go through [with the water sale], and it is disturbing.”

The squabbles over water in the Valley are understandably parochial affairs, turning on long-standing political and personal feuds and the peculiarities of the Rio Grande, and they seem to be divorced from the fact that the lower Rio Grande Valley is one of the fastest-warming parts of the country. Its residents, perhaps not coincidentally, also express a great degree of concern about climate change. In Hidalgo County, for instance, 77 percent of those surveyed for a 2016 Yale University study said global warming is happening, and 71 percent said they were worried about it — 14 points higher than the Texas average. In Starr County, just upstream from Hidalgo, 57 percent said they had been personally harmed by global warming — the highest percentage of any county in the United States.

Yet the region’s planners and elected officials don’t seem to have taken note. The regional water planning document makes only a passing reference to climate change and fails to account for its effects. Climate change is almost never mentioned by local officials, no matter where they stand politically. “Weather changes all the time,” Brand said. But there’s one thing he’s confident won’t. “We’re going to be fighting over water forever,” he said. “You don’t have water, you got nothing.”