Can Battleground Texas Save Wendy Davis’ Senate Seat?

It’s a steamy, hot summer morning in the Metroplex, and at the Dixie House, a Southern-style diner in east Ft. Worth where gravy flows like water, Libby Willis can’t find a moment to dig into her eggs and hash. She’s too excited about her campaign. Willis, the Democratic nominee in Senate District 10, is running in one of the state’s most important races for Democrats this cycle. It’s fallen to her—a first-time candidate with solid credentials—to defend Wendy Davis’ soon-to-be-former seat against Konni Burton, a fiery tea-party organizer who’d likely be one of the chamber’s most conservative senators.

Willis acknowledges that her odds are long in this Republican-leaning district. But the path to victory, she says, is simple enough. “We just got to get our people out to vote. That’s all there is to it,” Willis says. “This is not a sleepy year.”

Democrats faced a tough task holding onto the district even before Davis decided to try her hand at the governor’s race. Davis squeaked by in 2008 and 2012, when Barack Obama was at the top of the ticket and Democratic turnout was comparatively high. (Though Obama lost Tarrant County both times, Davis held on anyway.) But the last round of redistricting forced an early election in SD 10—the district now elects its senator in midterm years, when Democrats tend to falter in Texas. To hold the seat for Democrats, Willis will need luck, skillful positioning, a troubled opponent and an impressive field operation. That last part, Democrats hope, is where Battleground Texas comes in.

Battleground, the group started by former Obama campaign staffers with the aim of making Texas politically competitive, is spending most of its time and resources in the rocky terrain of the governor’s race these days. But down the ballot, the organization is trying to put muscle behind a dozen legislative candidates, running in marginal districts that should be fertile ground for Democrats. Dubbed the Blue Star Project, the effort aims to focus the group’s technical expertise and organizing ability on legislative races, with the help of a “coordinated field program and a full arsenal of data, digital, and communications expertise.”

What that means, in short, is that the group hopes to take the special sauce decanted from the Obama campaign’s field operation and drizzle it on legislative races here, where it might make more of a difference than it will against Greg Abbott, who has a 3-to-1 cash advantage over Davis. The most important of the races is SD 10. In the process, Battleground hopes to stake a claim to a continued future in the state.

Democrats everywhere hope this cycle will be more like a presidential year than, say, 2010, and if it is, Battleground could be part of the reason why. Willis says the organization is part of a longer push. “This is a multi-year effort. This is not one and done,” she says. “This is not, ‘Hey, we’re finished at midnight on November 4th.’ They are committed to continuing the work, which is fantastic. And really important.”

Willis has gotten some of the assists she needs if she’s going to prevail. First, in the GOP primary, Burton beat the more establishment candidate, Mark Shelton, a doctor who lost to Davis in 2012. Tarrant County hosts some of the most far-right groups in the state, from fringe tea party organizations to Open Carry Tarrant County, a gun group so whacked-out it was repudiated by the rest of the open carry movement. Burton comes from that element: She’s about as far from Davis, or Willis, as you can get.

So Willis is presenting herself as a bipartisan-minded moderate, with some success. She’s stayed competitive in the fundraising department, and has been endorsed by a number of unlikely groups for a Democratic challenger, including the generally establishment-oriented Texas Medical Association, along with law enforcement groups like the Combined Law Enforcement Associations of Texas, which only endorsed Republicans in statewide races.

It’s something of a cliché to say that the Democratic candidate represents the New Texas, and the GOP figure represents the Old Texas. That’s not the case here. Burton personifies the straining, ferocious conservative populism that’s emerged along with massive population growth in Texas suburbs. Willis seems rooted in the older Texas—she grew up in Abilene, but has long ties with the Ft. Worth establishment. She’s a known quantity here, someone who can talk credibly to different parts of the community.

If the national Republican Party is a vampire, Battleground is intended to be the wooden stake.

But her Texas roots go back further than all that. After we’ve ordered at the Dixie House, Willis informs me that the day we’ve met happens to be William Barret Travis’ birthday, and Travis, as it turns out, was great friends with Willis’ great-great-great-grandparents. “When Travis was on his way to the Alamo, he stopped at the house of David and Ann Ayres and left his son with them. The last letter he wrote in the Alamo was to David Ayres. And it starts: ‘Take care of my little boy.’

“Can you imagine? You’re at the Alamo, and you’re under siege. And he’s not thinking about himself, he’s thinking about his son,” Willis said. “In a way, that’s what this race is about—it’s about preparing for the future. It’s between the now, and the future. What are we going to do for our kids? What are we going to for our working men and women?”

It’s an intriguing metaphor, but Democrats across Texas have to hope Willis’ campaign goes smoother than Travis’ final defense on the morning of March 6, 1836. If the campaign—and in fact, if this election cycle as a whole—is going to be something other than a bloody, noble defeat, Willis and candidates like her need a hell of a lot of help. So Democrats have to put their hope in Battleground. Asked about the collaboration, Willis is all smiles.

“It’s a wonderful thing. SD 10 is really important for them. They’ve been canvassing since the first weekend in April for Wendy, and for me,” she says. “I believe that this will be really an enormous turnout operation. They’re ramping up. We’re closely coordinating with them. They have a great campaign staff, we have a great campaign staff, we’re integrated where we need to be. We feel very good about how big this effort’s going to be.”

Battleground Texas debuted in February 2013 to enormous fanfare. Democrats had just come off a spectacularly successful presidential election year: The blue portion of the electoral map had swelled in a way that made some gains seem semi-permanent. Formerly red states like Virginia, Colorado and Nevada had flipped, for reasons that included both shifting ideological coalitions and demographic changes. Other states, like Georgia, seemed to be in reach. Then there was Texas, the beating, blood-red heart of GOP electoral viability.

If the national Republican Party is a vampire, Battleground is intended to be the wooden stake. Founded by Jeremy Bird, the national field director for Obama’s 2012 campaign, and armed with the newest technology, techniques and tactics, the organization says it would do what the Texas Democratic Party couldn’t—or wouldn’t. Even if the group’s fresh-faced organizers don’t make a clean kill, softening Texas would mean national Republicans would have to spend time and money here. They’d win for losing. In a column for The New York Times, political reporter Thomas Edsall wrote a few months after Battleground’s launch that the group had “put the fear of God into the Texas Republican Party.”

Win or lose, Democrats are set to have a some long discussions about the future of the party after November 4.

If that fear was ever real, you can be sure that it’s dissipated a bit. Battleground has had a challenging first year and a half and its future is uncertain. Wendy Davis’ filibuster gave the Democrats what seemed like a viable shot at the governor’s mansion, so Battleground, which started as a long-term organizing project, wedded the group’s efforts to hers. Battleground handles the work in the field, and Davis’ campaign handles strategy and messaging. The two groups even share a bank account, called, promisingly, the Texas Victory Committee.

If Davis does well, Battleground has a chance to move up the clock on the state’s purple-fication. But if she doesn’t, Battleground stands to suffer along with her. The story of the 2014 election isn’t done yet, but Davis’ odds of victory seem slim. Even if she doesn’t win, Abbott’s margin over Davis matters quite a bit: If she outperforms expectations, Battleground—and the Democratic coalition more generally—will have something to show to donors and supporters come 2015. It’ll serve as a proof of concept.

If she does badly—if she ends up in Bill White territory, as seems possible—the whole thing will be a wash and Dems, having spent a hell of a lot of time and money for little in return, will be left asking themselves very tough questions about how best to organize themselves next cycle. A good deal of the enthusiasm that’s built up in the last year will fall apart. Battleground insists it’s here for the long term—but to make that a reality, the group needs to keep its raison d’être, and its appeal to big-money donors, intact. It’s an expensive operation to run. And some close to the state Democratic Party—which, mind you, doesn’t have a great track record of success itself—would like to see the party take on Battleground’s local organizing functions itself.

There’s already a lot of tension between Battleground and Democratic Party groups. A lot of that is normal political infighting—politics has plenty of big egos, and people don’t like being told what to do, especially when the interlopers come from out of state with an overriding confidence in their own wisdom. But some of the complaints seem more substantial. One odd thing: Battleground sometimes urges donors to give money to the group to “defeat Dan Patrick,” but the group isn’t really working with Leticia Van de Putte, who’s the one actually running against him—and has been left to run a relatively resource-starved campaign.

Battleground puts the information it collects on the state’s voters back into a shared database, called VAN, but not all of that data is equally available to all parts of the Democratic Party. Some is put in the “public” section of the database, accessible to all who use VAN, but other information is more closely held by the group. In the past, Democrats have run coordinated efforts in which information on voters was more freely traded between different campaigns and groups. Leaders and organizers with local party groups—who organize their own block-walking and GOTV campaigns—say they don’t have all of the information they need to make the most efficient decisions about how to deploy their limited resources.

County parties have been left to work out individual agreements about sharing that valuable data, which contains information about how to better target voters. One party organizer, who generally lauded Battleground and said that the coordination between different parts of the Democratic coalition is “better than it has ever been,” nonetheless described the approach as evidence of Battleground’s “divide and conquer” mentality towards the party. As an explanation, some point to Jeremy Bird’s important role in the nascent Hillary Clinton presidential campaign. Unlike the Democratic Party, there’s nothing to stop Battleground from taking sides in contested primaries, and Battleground could become Clinton’s field arm in Texas. Erica Sackin, the Battleground Texas spokesperson, told the Observer that the Democratic coalition was “working together this year in unprecedented ways” and “doing all we can to turn out the vote for the incredible slate of candidates we have on the ballot this November.”

Win or lose, Democrats are set to have a some long discussions about the future of the party after November 4. If this cycle ends in a comprehensive defeat—bad margins at the top of the ticket, and few downballot victories—that conversation could turn bloody. That’s one reason Abbott’s campaign is spending time and money in the Rio Grande Valley these days—an area that’s a significant reach for him, electorally. “This is not about beating Wendy Davis,” an unnamed Abbott advisor told The Dallas Morning News about efforts in the Valley. “This is about beating Battleground Texas.” If Abbott can run up the score on Davis this cycle, GOPers know the chaos it could cause for Dems down the road.

That’s one reason the Blue Star Project is important to the group—if Battleground can pick off a number of legislative races this year, it gives them a plausible claim to a future in Texas. None of the twelve races Battleground is assisting in are really “reach” districts, but Texas Democrats have had trouble pinning them down. If a couple of them flip blue in November, Jeremy Bird’s young group will argue it’s brought home enough trophies to justify another hunting trip.

The 2016 election cycle will likely see Clinton at the top of the ticket driving high turnout among the Democratic base, which means it could be a good year for Dems in legislative races here. In 2008, Democrats in Texas rode the coattails of Barack Obama’s popularity to win 74 of the state’s 150 House seats. It’s not realistic to hope for that again—not least because the state had another round of gerrymandering in between then and now—but it could be a more comfortable climate, and Battleground’s experience this cycle in down-ballot races could prove useful.

Of the races Battleground is participating in, a number are in the Dallas–Fort Worth Metroplex, where the group is headquartered. There’s Willis’ race, of course, but in the House there’s other low-hanging fruit here for Democrats that the party hasn’t managed to pluck in recent cycles.

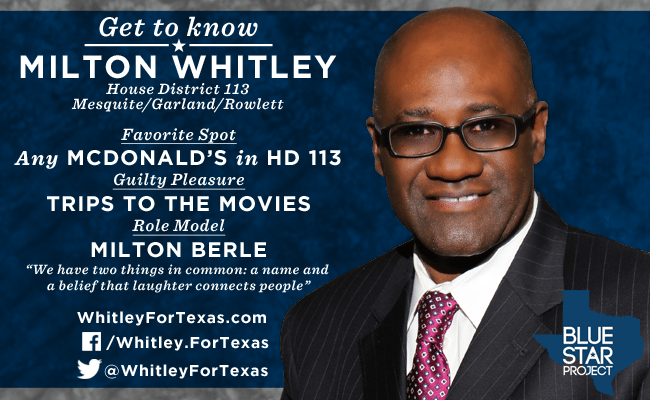

Carol Donovan and Milton Whitley in House Districts 107 and 113, respectively, are facing incumbent Republicans in potentially soft districts.

If Davis does well, Battleground has a chance to move up the clock on the state’s purple-fication. But if she doesn’t, Battleground stands to suffer along with her.

Elsewhere in the state Battleground is backing candidates like Susan Criss, who’s hoping to replace Craig Eiland as Galveston’s representative, and Kim Gonzalez, who’s challenging J.M. Lozano in Kingsville, who defected from the Democratic Party to become one of the legislature’s three Hispanic Republicans.

In House District 105, there’s Susan Motley, who’s running against former state Rep. Rodney Anderson to replace outgoing GOP state Rep. Linda Harper Brown, who struggled to keep the district Republican—in 2008, she won the seat with only 48.7 percent. Republican margins of victory have been steadily declining in the area over the last decade. Recently, for whatever it’s worth, The Dallas Morning News endorsed Motley.

Motley is another first-time candidate, who says she decided to run after two events last summer: The special sessions consumed by anti-abortion legislation, combined with Perry’s veto of the equal pay bill that’s become an issue this cycle, was “the straw that broke the camel’s back.” She’s a labor and employment lawyer, and the veto of the bipartisan bill to make it slightly easier for workers to address pay discrimination left her steaming.

Away from the power struggles and back-room recriminations—and Austin’s entrenched skepticism—there’s still an election in progress. Thanks in part to Davis, there’s been a swelling in the ranks of Democratic volunteers across the state, many of them joining a campaign for the first time, and Battleground hopes that volunteer base will prove a long-lasting legacy of the group’s first election cycle, whatever the result in November.

After breakfast at the Dixie House, Willis heads off to a canvassing effort organized by Battleground for her campaign. Volunteers will be reaching out to carefully targeted households near Meadowbrook Elementary School, in east Ft. Worth.

There’s a small turnout, but in these volunteers, Battleground sees the seeds of change. Gary Coulter, a former professor at Tarrant County Community College, came out to canvas for Willis after a long period of relative disengagement with Texas politics. This was the first campaign he’d worked since George McGovern in 1972.

“Every canvas I’ve gone on and every phone bank I’ve worked on, we’ve recruited new volunteers.” He’d never seen Burton’s people walking the district.

“I’m in it for the long run. I feel like what we’re doing now is the start of a wonderful building process,” Coulter says.