Texas Legislature Adjourns Without Adding Money for Census Outreach. That Could Cost the State Billions.

With the census becoming more politicized under Trump, Republicans shied away from spending money to ensure all Texans get counted.

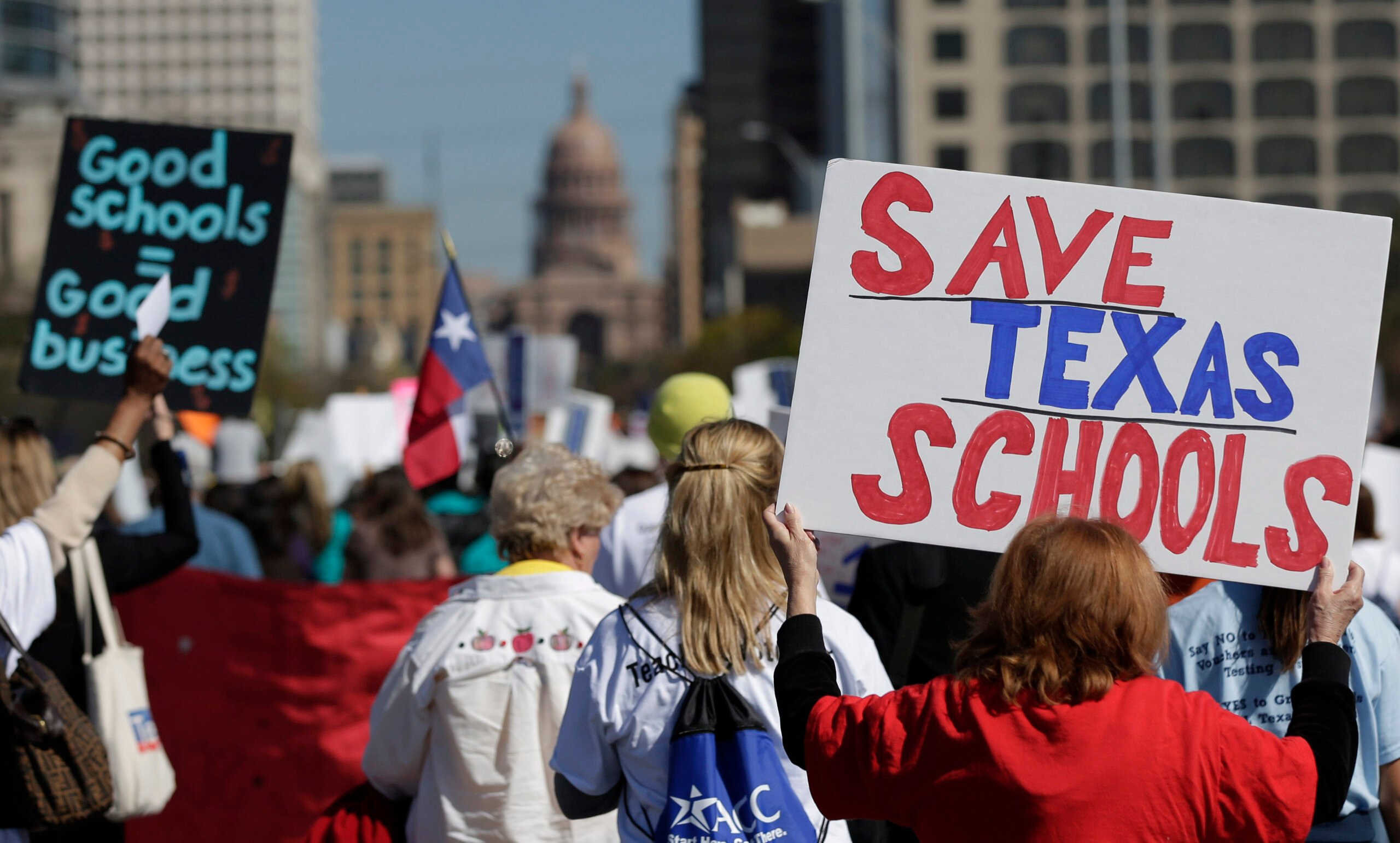

Texas has big things at stake in the 2020 U.S. Census: billions of dollars in federal funding and congressional seats that could give the state a bigger say in Washington, D.C. Between that and Texas’ history of being undercounted, Democratic lawmakers and policy analysts pushed this legislative session for the state to create a complete count commission and to allocate funds for community outreach. But in a time when the census is tinged with partisan politics — mostly over Trump’s proposed inclusion of a citizenship question — Texas lawmakers adjourned without taking action to ensure a complete count.

State Representative César Blanco, D-El Paso, and Senator Juan Hinojosa, D-McAllen, filed bills to create a committee that would develop a strategy to ensure everyone is counted. The bills also would have allocated money to offer grants for local outreach efforts such as town hall meetings, community events, newsletters and other promotional documents, and census worker recruitment. Neither of the bills was given a committee hearing.

The two Democrats also unsuccessfully attempted to apportion money in the state budget for census outreach. Blanco’s proposal called for $50 million for the statewide complete count commission and another $50 million to offer local community grants; Hinojosa’s rider asked for a much more conservative $5 million for grants. Neither made it to the final state budget.

“It’s disappointing that we lost our shot,” Blanco told the Observer. “It wasn’t a priority for this legislative body, unfortunately.”

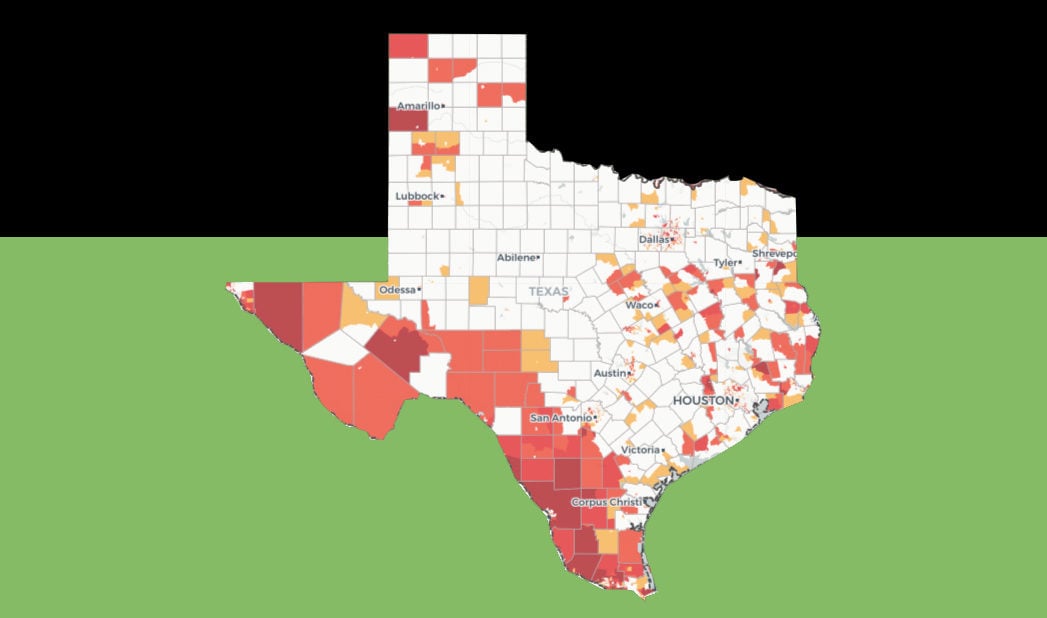

Texas has one of the biggest shares of hard-to-count communities in the country: 25 percent, or about 6 million people. Those are groups with low census response rates, including immigrants, people of color, residents of rural areas and very young children. A George Washington University study found that a 1 percent undercount in the census could result in at least $300 million in federal funding lost for Texas every year for 10 years, the interval in which the census is performed. Losses would erode programs whose federal funding relies in part on census data, such as special education grants, foster care, highway planning and construction, and health care services for low-income and elderly people.

The census counts also determine the number of each state’s representatives in Congress and presidential electoral votes. Texas could gain up to three new congressional seats after the 2020 Census, more than any other state stands to gain, but an undercount could cost Texas those potential seats. That shift in political power could be significant as the state shows signs of turning blue.

“They didn’t see the big picture. They were thinking about the short-term racial implications of counting every single person, and I think that’s disappointing.”

Many Texas Republicans believe it’s up to the U.S. Census Bureau to shoulder costs for census outreach, Blanco said, but the bureau has been underfunded by a total of $200 million since 2012. Supporters say the money is an investment that should return more than the upfront costs. That’s why more than half of states have made their own plans to ensure an accurate count of their populations in 2020. California has allocated more money for census outreach than any other state, with $100 million for 2018-19 and another $54 million proposed by Governor Gavin Newsom for 2019-20.

“If we don’t step up, the reality is California’s going to eat our lunch,” Blanco said at a press conference in April.

But it was an uphill battle in Texas amid controversy created by the Trump administration over adding a citizenship question to the census. Experts say Trump’s effort to add the question — which has been the subject of several lawsuits and may be upheld by the U.S. Supreme Court — would deter noncitizens from participating, with the greatest potential drop among Latinos and foreign-born residents.

“This issue has been highly politicized. It shouldn’t be,” Blanco said in April. “The Constitution clearly does not delineate between citizen and noncitizen. It says all people, whole people.”

In Texas, most of the tracts threatened with significant undercounting because of the citizenship question are along the state’s border with Mexico. That includes some of the poorest communities in the country. A 2000 study for the U.S. Census Monitoring Board showed that Texas was one of the three states with the largest federal dollar losses due to undercounts. That year, seven Texas counties were among the 25 in the country that saw the largest undercount rates.

Asked why Blanco’s proposals were left out of the state budget, state Representative John Zerwas, a Republican who is the chief budget writer in the House, said Blanco had requested a “sizable amount of money.”

“I think Representative Blanco had a very good narrative around it as to why it’s important that we maximize our census count, and nobody would disagree with him on that,” Zerwas told the Observer. “I think there was some concern in dedicating that amount of money to that effort right now when we had so many other priorities that were in the budget.”

Governor Greg Abbott has the authority to issue a proclamation to create a complete count commission, but without funds set aside, it would be mostly symbolic, said Luis Figueroa, legislative and policy director for the Center for Public Policy Priorities, an influential left-leaning think tank. It’ll be up to local communities — whose budgets have been increasingly kneecapped by the Legislature — to fill that void, relying on city and county funds and philanthropic foundations.

Ultimately, lawmakers could have found the money to increase census participation, but the obstacle was a lack of will, Figueroa said, adding that the controversy around the citizenship question scared off some members in the Republican-controlled Capitol.

“Unfortunately, there is a racial aspect and a concern that if we count all the people living in Texas, including immigrants of all statuses, that has some type of negative consequences for [Republicans],” Figueroa said. “They didn’t see the big picture. They were thinking about the short-term racial implications of counting every single person, and I think that’s disappointing.”