A Century After the Porvenir Massacre, Remembering One of Texas’ Darkest Days

Most Texans still don’t know about one of the cruelest atrocities in their state’s history.

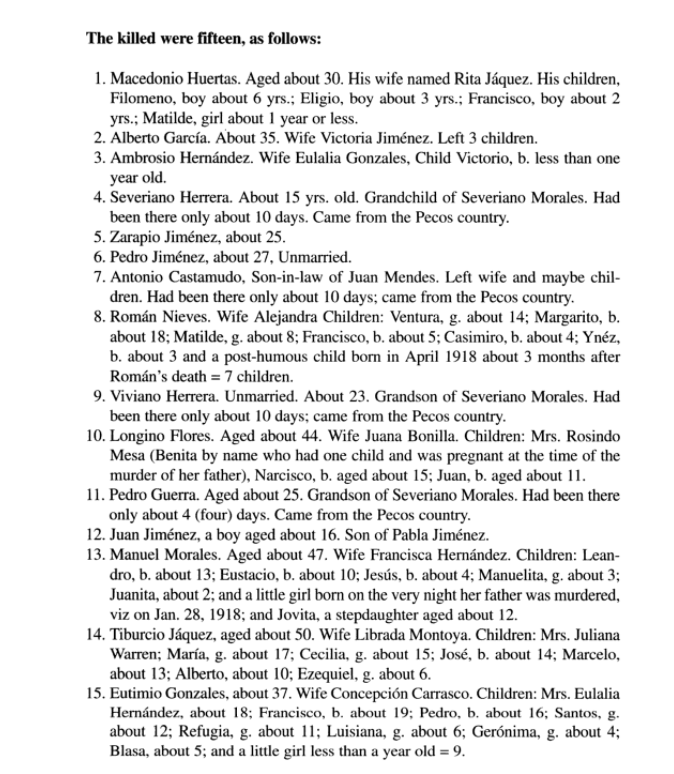

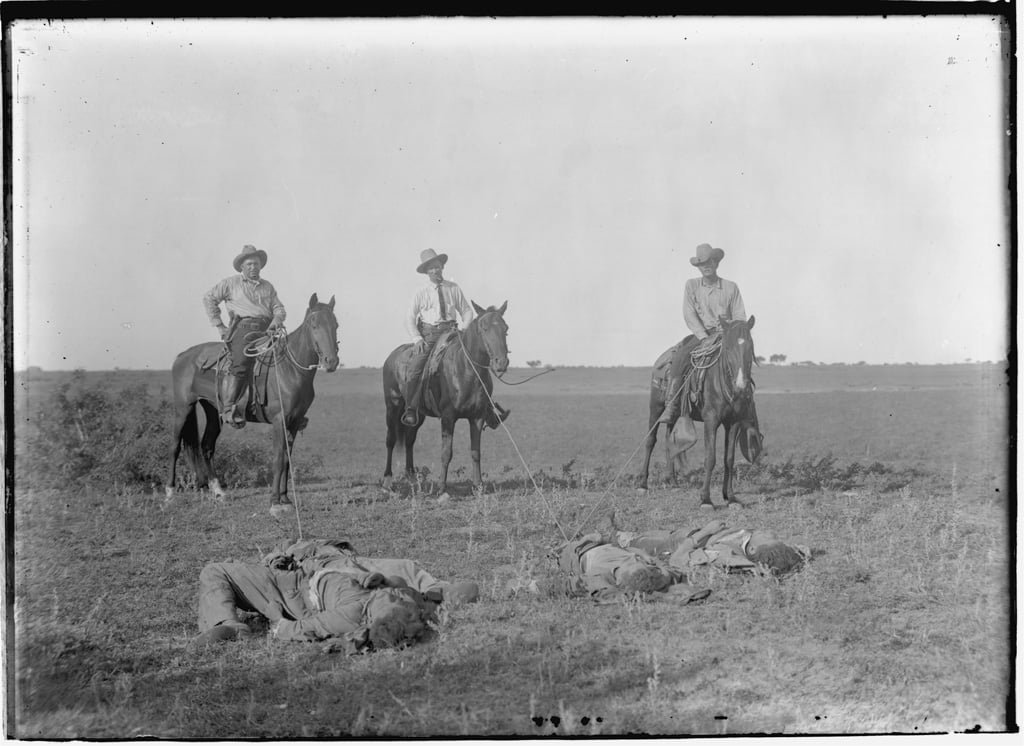

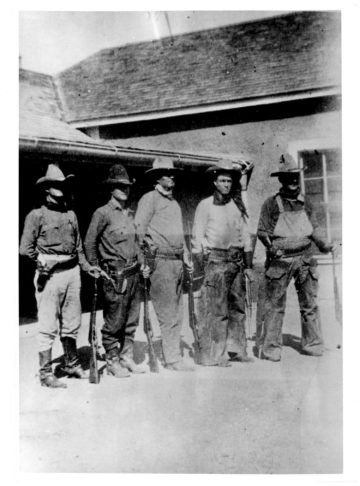

On January 28, 1918, a band of Texas Rangers and ranchers raided the tiny Presidio County village of Porvenir in the middle of the night. The rangers were angry about a series of recent cattle raids by Mexicans along the border. Though there was no sign anyone from Porvenir had been involved, they decided to make an example of the town, whose 140 or so residents were poor farmers of Mexican descent. In the dark, the raiders forced 15 men and boys out of the thatched-roof adobe huts where they were sleeping, marched them to a nearby bluff and shot them all.

The rangers claimed they were ambushed by the villagers — a story that went largely unchallenged until 2002, when archaeological research proved that all the bullets fired that night were government-issued. Still, most Texans don’t know about one of the cruelest atrocities in their state’s history.

That may be changing. On a sunny Sunday afternoon, about 400 people gathered in an auditorium at the Texas Capitol to commemorate the 100th anniversary of the massacre. Among the somber crowd were lawmakers, historians and activists, as well as about 300 descendants of the victims. They traveled from states as far-flung as New York, California, Florida, Washington and Arizona for the event.

State Senator Jose Rodriguez, D-El Paso, whose district includes the land where Porvenir once stood, announced a plan to place a historical marker nearby.

“No amount of explanation about the general sentiments or the atmosphere at the time can explain or justify what happened,” Rodriguez said. “It does not explain, excuse or mitigate the widespread lynchings that took place up and down the border.”

In addition to honoring those who were killed, the event recognized Jose Canales, a state senator at the time who pushed for a legislative inquiry into the massacre, and Harry Warren, a local teacher who visited Porvenir the day after the slaughter and wrote a scathing report. Warren described how the rangers “took the men and boys out of their warm beds, they [were] making no resistance whatever” before shooting them. He added that the bodies were found “lying together, side by side,” and that the village’s only white resident was spared. As E.R. Bills writes in his book Texas Obscurities, Warren’s story was “problematic for the Ranger account … [Warren] unequivocally termed it a massacre.”

No criminal charges were ever filed against the Rangers, though the legislative inquiry did lead Governor William Hobby to disband Company B, the group that led the massacre. James Monroe Fox, the ringleader, retired voluntarily and re-enlisted with the Rangers a few years later.

“[Fox] submitted false reports of what happened in the days and weeks following the massacre,” said Monica Muñoz Martinez, a Brown University historian who studies racial violence. “It has taken 100 years to change that story.”

The Capitol event ended with a candlelight ceremony and an original song about the massacre by Brandi Tobar, a descendant who traveled from Arizona.

Arlinda Valencia, a descendant who helped organize the event, said she hopes the true story of Porvenir, the now-abandoned border town whose name means “future,” will soon be better-known.

“Their blood still runs deep in this room and in the veins of us,” said Valencia. “We are the descendants, and we are the ones who will not let anyone forget.”