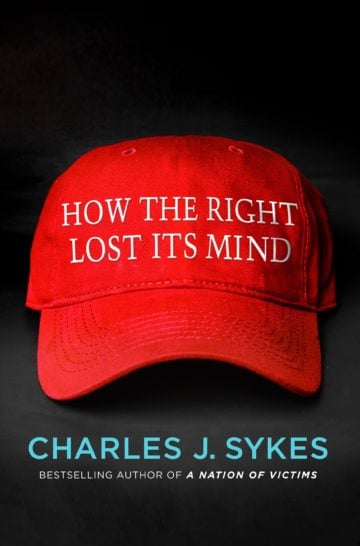

Charlie Sykes’ New Book Shows ‘How the Right Lost Its Mind’

The book is a comprehensive dismantling of a party that has seemingly lost not only its moral compass, but even its ability to decipher fact from fantasy.

In March 2016, Charlie Sykes was a successful radio host and author in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, when Donald Trump phoned his show. The Republican primary was days away, and Trump hoped an interview with Sykes — an influential pundit boasting a dedicated local audience — would rally support among state Republicans. But the call didn’t go as planned. Sykes, a “contrarian conservative” and early #NeverTrump-er, challenged the candidate on his treatment of women, his false statements about Wisconsin Governor Scott Walker and especially his conservative credentials.

After blasting Trump for donating “hundreds of thousands of dollars” to Democrats over the years, Sykes reminded him of the many times he had advocated for Democratic policies, such as when he had praised Obama’s stimulus; “called for the largest tax hike in history”; and endorsed universal health care, gun control and “abortion on demand.” Sykes even suggested that Trump’s newfound conservatism was “one giant fraud.” It was rare for a conservative journalist to challenge Trump so pointedly, and Sykes’ approach was lauded by many across the political spectrum. But the far-right viewed it as a betrayal. Sykes was inundated with hate mail and threats, even branded a “cuckservative.” By December, Sykes, whose show had been on the air for 23 years, called it quits.

by Charles J. Sykes

ST. MARTIN’S PRESS

$27.99; 288 pages

In his new book, How the Right Lost its Mind, Sykes portrays the Trump interview as a culminating moment in shaping his views about the state of American conservatism. Immediately after the interview, Sykes began appearing all over the media, declaring that he could no longer rationally debate his audience. Many of his listeners, he asserted, had become immune to facts, trapped inside a conservative media bubble that left little room for critical thinking. Sykes told Business Insider that many of his listeners had ceased believing mainstream publications altogether, assigning more credibility to Facebook posts and crackpot theories than New York Times articles. “You can’t go to anybody,” he said of his listeners, “and say, ‘Look, here are the facts.’”

How The Right Lost its Mind seeks to explain how this happened. Why, Sykes asks, did vast numbers of conservatives eschew both principles and fact-based reasoning in the 2016 election? While the book is not really about Trump, it targets the right-wing media for establishing an echo chamber that allowed him to become president. Sykes’ central premise is that conservative thought leadership has been stolen away from moral, principled thinkers — he cites George Will, Jennifer Rubin and William Kristol, among others — by bombasts, opportunists and conspiracy-mongers, such as Sean Hannity, Alex Jones, Ann Coulter, Tomi Lahren and Rush Limbaugh. These opportunists, he argues, have spent 20 years attacking the mainstream media, resulting in a degradation of the idea of objective truth.

The disintegration of principled conservatism, Sykes contends, was sparked by plain old greed.

“What we learned,” Sykes writes of the 2016 election, is that “the walls are down, the gatekeepers dismissed, the norms and standards of journalism and fact-based discourse trashed.” While Sykes admirably accepts his own share of blame in constructing the right’s bubble (he admits to overdoing the attacks on the establishment press and insufficiently condemning demagogues, like Ann Coulter, who appeared on his show), his book suffers from a conspicuous omission: Sykes never faces up to the fact that key pillars of contemporary conservatism, particularly trickle-down economics, have been abject failures. A party without good ideas, after all, is much more likely to turn to the cranks.

The watershed period was the post-Reagan years. That’s when conservative media trailblazers Rush Limbaugh, Rupert Murdoch and Roger Ailes launched their shows. Sykes examines their influence on modern firebrands and the recent election. In his telling, the story is a tragedy. These trailblazers, he argues, astutely identified a defect in the establishment media — liberal bias — but went wrong by approaching it as a business opportunity rather than a journalistic problem. Limbaugh and Ailes didn’t set out to be less biased and more accurate in their reporting than the outlets they castigated; they set out to sell a product to an audience that craved an alternative worldview. The disintegration of principled conservatism, Sykes contends, was sparked by plain old greed.

Sykes contrasts the staid and intellectually consistent styles of his conservative heroes (he mentions Burke, Tocqueville, Buckley and Reagan) with the sensational and paranoid styles of contemporary stars. The formula for the latter has been simple and cynical: Shape the news to fit a specific worldview, dumb it down to appeal to the masses, and crank the outrage to 11. Success is measured by audience size, not how well you’ve informed them. Sykes spends a lot of time discussing the misinformed electorate. In a chapter titled “The Attack on the Conservative Mind,” he unveils polls revealing how severely misinformed many conservatives are: 59 percent still believe Obama was not born in the United States, for example, with 65 percent still believing he’s a Muslim. He also cites fake news creators who tell us that conservatives are far more vulnerable to their product than liberals are.

While some of these points have been made before, Sykes’ status as a liberal-turned-contrarian conservative adds weight to his arguments; he isn’t a strict partisan. And while he also criticizes the left’s bubbles, he shows that misinformation has been far more prevalent on the right because the agenda of the new right media has been more blatantly entertainment-driven. “Beyond the short skirts and low decolletages for on-air women that Ailes preferred,” he writes of Ailes’ agenda, “there were stories that were hyped, narratives advanced, and candidates boosted.” He also nails Fox for flipping from Trump critic to Trump cheerleader for purely cynical reasons: “The network’s pro-Trump shift had more to do with ratings than with ideology.”

There’s a lot to admire in Sykes’ analysis. His attacks on the hypocrisy of evangelicals in embracing Trump particularly hit their mark, and he eviscerates the alt-right for “confirming the worst stereotypes” of the left’s portrayal of a racist right. But it’s his theme of greed undermining conservatism that truly resounds: He tells us, for example, that the majority of money raised by tea party PACs was never used to elect candidates but simply pocketed. The book is a comprehensive dismantling of a party that has seemingly lost not only its moral compass but even its ability to decipher fact from fantasy. But the book’s chief flaw hovers over every chapter.

On September 14, 2012, the nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office released a study that examined the economic effects of cutting taxes on the wealthy. Ever since Reagan slashed the top marginal tax rate from 70 percent down to 28 percent in the ’80s, Republicans have worshipped trickle-down economics as their go-to policy for growing the economy. The study found, however, that reducing the top tax rate “appears to be uncorrelated with … productivity growth. The top tax rates appear to have little or no relation to the size of the economic pie.” It added: “the top tax rate reductions appear to be associated with the increasing concentration of income at the top of the income distribution.” Congressional Republicans buried the study.

Any book that purports to explain the right’s turn toward cranks and snake-oil salesman must grapple with the fact that its signature economic policy over the past 35 years has promised prosperity but delivered inequality.