Cheaters Beware: TEA Says It’s Ready to Catch You Now. For Real, This Time.

One of the nice things about starting a new job is that nobody can blame you for mistakes that happened before you arrived.

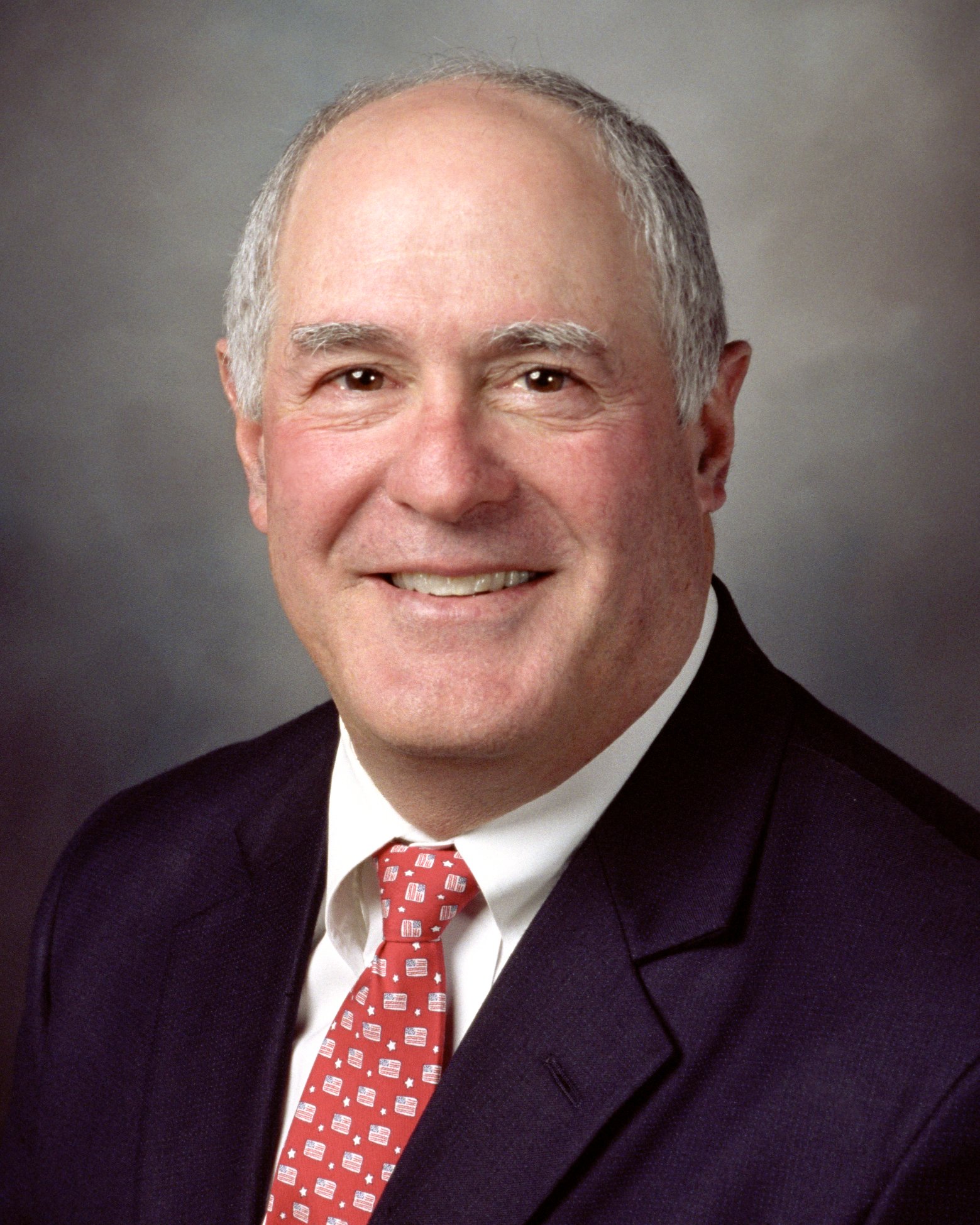

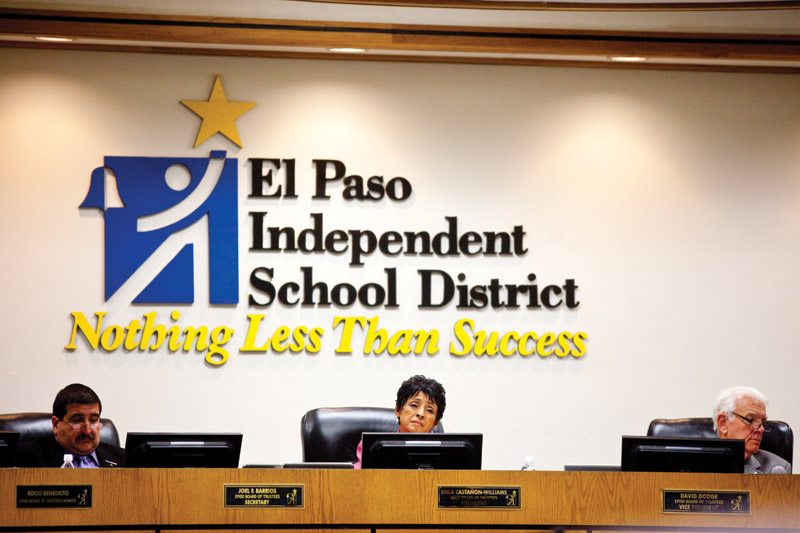

Michael Williams, for instance, must have been thrilled to take over the Texas Education Agency a year ago, and not have to answer for TEA’s colossal inaction in response to cheating complaints at El Paso ISD. Twice in 2010, TEA cleared El Paso ISD of wrongdoing—before a federal investigation confirmed the district was “disappearing” low-scoring students to game federal accountability ratings, carrying out one of the most nefarious cheating schemes ever in U.S. schools.

Not long after he became education commissioner, Williams pledged to get to the bottom of TEA’s failure, asking State Auditor John Keel to investigate all the nasty stuff that went on before he got there.

The state auditor’s report was released a week ago. It pretty much confirms early EPISD whistleblowers’ concerns that TEA was (a) uninterested in investigating their complaints and (b) overmatched by then-Superintendent Lorenzo Garcia’s scheme. The El Paso Times, which got an early copy of the audit, summed it up in the headline, “Texas Education Agency can’t spot cheating.”

Williams made the most of the moment, telling the Times that TEA’s past response was “an entire organizational breakdown and … started with the old leadership team.” But now, he assured them, there’s a new sheriff in town: “This is a new agency, this is a new leadership team and this leadership team understands the importance of aggressively ferreting out and identifying the truth.”

Williams said nobody at the agency will be punished based on the audit’s findings. He blamed leadership and institutional shortcomings at TEA, which is consistent with the new audit. I’ve highlighted a few choice passages from the audit below, but the main takeaway is that TEA is not built to catch the kind of cheating that went on at El Paso ISD and, it seems, other districts around the state.

If a district is mishandling state money, or if teachers are helping students to cheat on tests, TEA has ways to investigate those complaints. But if whole groups of students are being misclassified or shooed away from class to boost a school district’s test scores, the agency is paralyzed. While they don’t dwell on TEA’s shrinking staff and funding over the years, auditors note that TEA is poorly outfitted for fraud-catching, with just one investigator.

One TEA employee told auditors she’d been suspicious of the miracle turnaround underway at EPISD, but didn’t know who to tell about it. TEA’s plan for monitoring districts, according to the audit, “does not encourage Agency employees to initiate investigations based on observations and professional judgment.” And when the U.S. Department of Education directed TEA to investigate 10 complaints from then-state Sen. Eliot Shapleigh, TEA’s investigators decided half of them were outside the agency’s jurisdiction, and never followed up.

State auditors recalled the time in 2009 when the Winfree Academy Charter Schools around Dallas rearranged their students so none were listed as 10th graders—meaning there’d be no test scores on which to base a federal rating—and TEA only caught it after receiving an outside complaint.

That, too, was on former commissioner Robert Scott’s watch. (Scott didn’t reply to a voicemail from the Observer, nor has he spoken with other media about the new audit.) But blaming the old boss for TEA’s shortcomings doesn’t quite explain what went wrong.

The Dallas Morning News was quick to point out TEA’s cursory investigation—before Scott’s arrival—after a Morning News report uncovered many schools making “statistically improbable gains” in test scores. TEA did hire an outside investigator, which found hundreds more suspicious schools. TEA responded with swift and ruthless justice… by sending those schools a questionnaire about their test security.

But why stop there? Walt Haney, the Boston College researcher famous for debunking the “Texas Miracle” of rising test scores in the ’90s, analyzed statewide enrollment by grade in 2001. His results, he wrote, “clearly suggest the possibility that after 1990-91, when TAAS was first implemented, schools in Texas have increasingly been failing students, disproportionately Black and Hispanic students, in grade nine in order to make their grade 10 TAAS scores look better.”

Superintendent Lorenzo Garcia’s way of “disappearing” students from the 10th grade was a particularly nasty rendition of the same old con. So long as there’s such a huge incentive to raise test scores, administrators will keep finding creative ways to beat the system. And when the state’s investigators are underfunded and uninterested, it’s that much easier for cheaters to get away with it.

Now, at least, Michael Williams says TEA is ready to get proactive. TEA responded to the state audit by announcing that it will create a new office dedicated to these investigations. The agency will start watching districts’ enrollment and testing data for funny stuff. And as for TEA’s outdated complaint tracking system, the one that made it so hard to communicate within the agency—they began work on its replacement six years ago. According to TEA’s response to the audit, there was just one problem:

“The project was not able to be completed due to budget constraints and resource limitations.”