My Great-Grandfather Was a Racist

Once we take down Confederate statues, Texans must still grapple with monsters in the past.

A version of this story ran in the September / October 2023 issue.

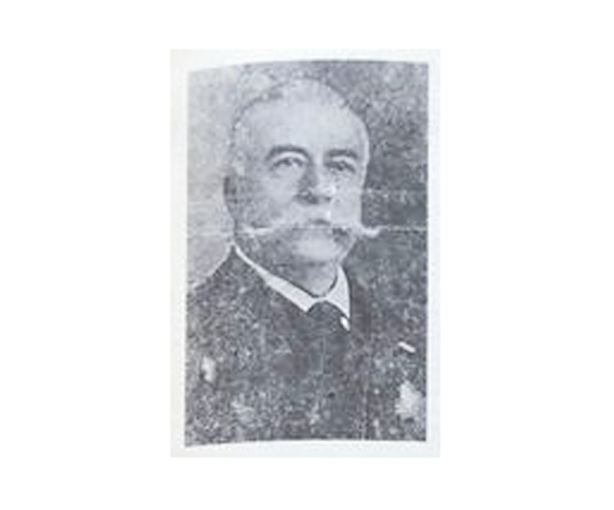

My great-grandfather, José-María Arana, was a racist.

After the United States barred Chinese men from immigrating under the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, tens of thousands sought a new life in Mexico, where they faced no warmer a welcome as they established themselves. A former schoolteacher and businessman, José-María led a vicious campaign against the Chinese in the Mexican states of Sonora, Sinaloa, and Baja California in the early 1900s.

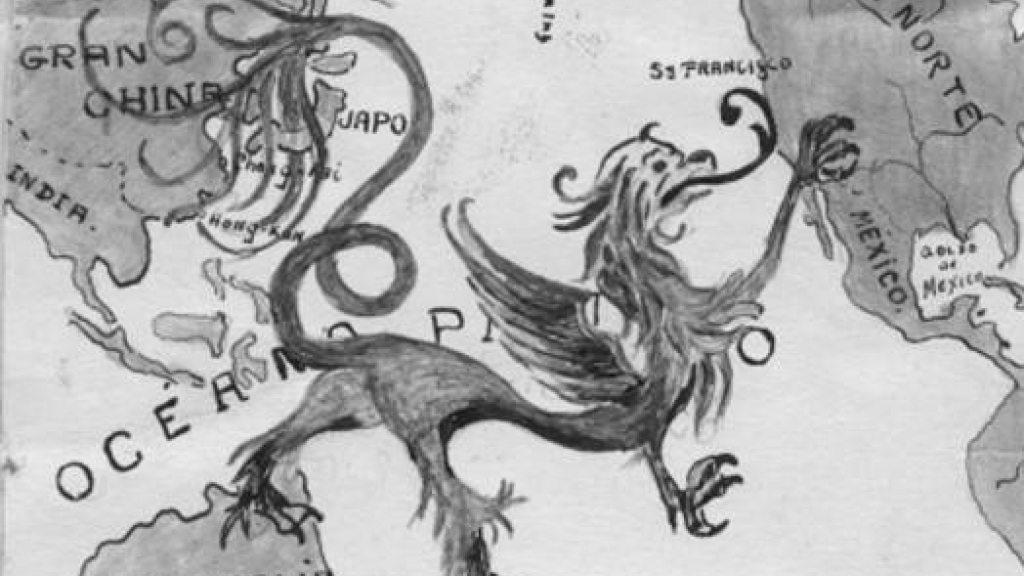

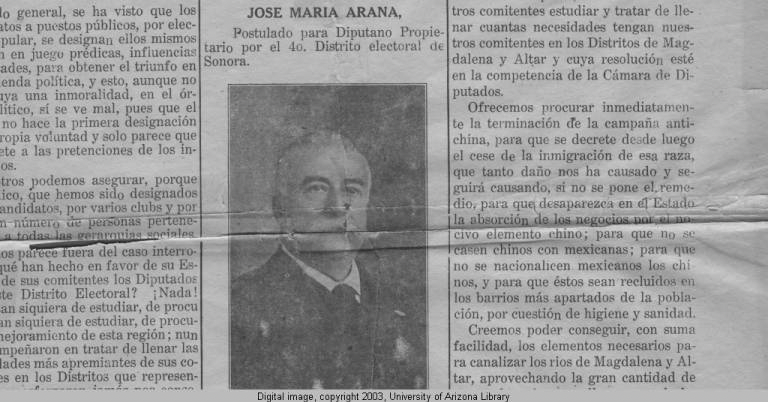

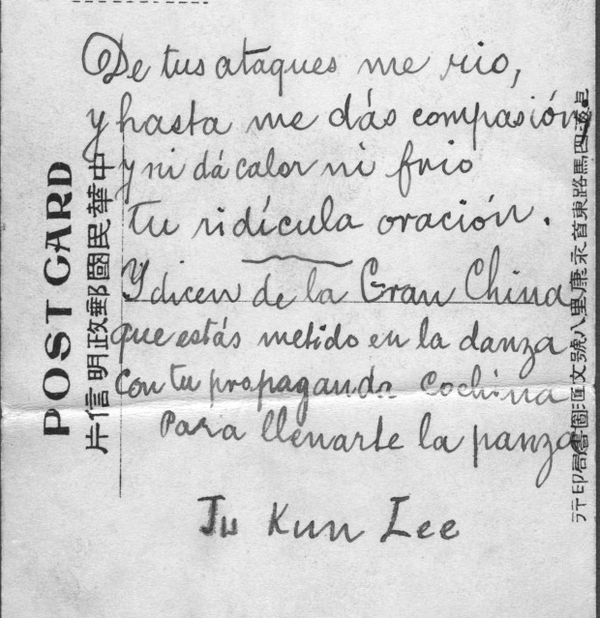

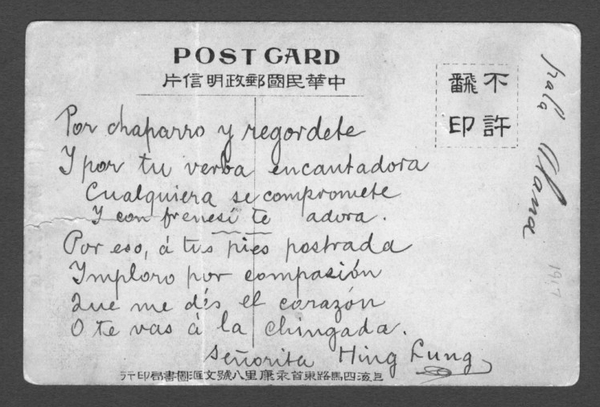

Seeking “all legal means to eliminate the Asian merchant,” whose growing prosperity he viewed as a threat to the working class and Mexican national identity, José-María formed a junta of local businessmen in 1912 to address what he called “the tremendous calamity of the Chinese jaundice.” He launched a newspaper, Pro-Patria, whose masthead boldly proclaimed, “Mexico for the Mexicans and China for the Chinese.” Featuring racist jokes and caricatures, the broadsheet portrayed Chinese immigrants as carriers of disease and a threat to Mexican women.

“We cannot live together because there exists an absolute incompatibility in race, social customs, and economy,” José-María wrote in its pages.

My great-grandfather carried his message throughout Northern Mexico, making speeches in working-class towns like Cananea—whose poor copper miners he thought ripe for radicalization—and urging city and state leaders to restrict the types of businesses that Chinese immigrants could run, relegate them to ghettos, and expel them de manera definitiva [in a definitive way].

I’ve thought increasingly about my great-grandfather and his ignoble legacy as I’ve settled into life in Texas, where the Confederate cause is memorialized on statues, flags, and street signs. Growing up on the U.S.-Mexico border in Nogales, Arizona—where José-María’s widow, my great-grandmother, settled after his death in 1921—I knew little about my family tree’s racist roots. Like a lot of gay kids who come from a small town, I left to find people like me in bigger cities and only much later started to contemplate my origins.

A few months after moving here in the summer of 2022, I visited the Capitol grounds with my in-laws from London. The Texas State Capitol is an imposing Renaissance revival structure made of pink granite with a dome that, Texans remind you, is taller than the U.S. Capitol. But what impressed us all the most on that first visit was the enormous Confederate Soldiers Monument on the right as one walks up to the entrance from 11th Street.

A bronze statue of Confederate President Jefferson Davis stands atop one of five pillars, the other four support figures representing the branches of the Confederate military. The inscription on the pedestal below commemorates the 437,000 soldiers who “died for states [sic] rights guaranteed under the Constitution” and asserts that “the People of the South, animated by the spirit of 1776, to preserve their rights, withdrew from the federal compact.”

“It’s Texas,” I said preemptively, feeling defensive and embarrassed at the same time as my in-laws looked on in horror. It’s the same way I feel when an outsider mentions the state’s abortion ban or attacks on LGBTQ+ people.

The Confederate Soldiers Monument is one of 12 memorials on the grounds that perpetuate the “lost cause”—the historical myth that the Confederate cause was heroic and not about slavery.

I’ve thought increasingly about my great-grandfather and his ignoble legacy as I’ve settled into Texas, where the Confederate cause is memorialized on statues, flags, and street signs.

It is a lie easily debunked by looking at Texas’ Ordinance of Succession, which laid out the state’s own reasoning for withdrawing from the union. The document declares that Blacks were “rightfully held and regarded as an inferior and dependent race” and that “the servitude of the African race … is mutually beneficial to both bond and free” as well as ordained by God. Even the monument’s Confederate death count, scholars have pointed out, is inflated.

The endurance of the Confederate cult here does not, of course, reflect the prejudices of most Texans, which is what makes these symbols so corrosive to a shared sense of state identity. An implicit endorsement of white supremacy, they most directly exclude Black Texans, whose struggle for freedom offers a far more edifying narrative to rally around—one that embodies our national values and unity rather than doubling down on a lost war. But they set up an identity conflict for anyone of good conscience who wants to claim Texas as their own: Every assertion of Texas identity must come with a “but.”

Reminders of the Confederacy abound here in Austin, considered the state’s bluest city: In the Texas State Cemetery, civil rights hero and Congresswoman Barbara Jordan and former Governor Ann Richards lie yards away from Albert Sidney Johnston, a slave owner and Confederate general whose Gothic tomb looks out on the Confederate Fields on the cemetery’s southeast side, where 2,200 Confederate veterans are interred, each plot marked by a white cross.

Some of my Southern friends have said that when you grow up in the South, the paraphernalia is so commonplace, it can blur into the background. But if you’re new to it, it’s striking to see the resentments of the 1800s enshrined in what are supposed to be shared expressions of our civic ideals.

It was perhaps easier to dismiss them before the Obama and Trump presidencies brought the Nazis and white, Christian nationalists out of the woodwork, when it was at least a bit more plausible to reassure oneself that “America is getting better.” It’s become harder to think of racism as a healing wound on the body politic when white nationalists demonstrate openly in public and Republicans in the Legislature try to ensure K-12 students only get taught a sanitized fairy tale about Texas history.

“Most Texans do not support erasing our history … out of political correctness,” Lieutenant Governor Dan Patrick wrote in an August 2022 letter to Senate Democrats who had urged the Legislature to remove Confederate monuments on the Capitol grounds.

The irony is that whitewashing Texas history is the very purpose of Confederate propaganda—and the impetus behind state Republicans’ attacks on education. Last year, Governor Greg Abbott signed a law that limits how K-12 teachers can talk about racism and slavery; it bans educators from discussing the New York Times’ 1619 Project, which reframes the nation’s founding as inextricably linked to the arrival of slaves on American shores in 1619.

Whitewashing Texas history is the very purpose of Confederate propaganda.

Since the “Unite the Right” rally in Charlottesville, Virginia, in 2017, and the George Floyd protests in 2020, some Texans have begun to change their minds about memorializing the Confederacy. While a bare majority once opposed their removal, now 52 percent say they should be taken out of public view or relocated to museums where they can teach us about the past rather than help keep its prejudices alive.

Amid our national reckoning about race, reminders of the Confederacy have started to come down in Texas. In 2017, the Texas State Preservation Board voted to remove the Children of the Confederacy plaque, which proclaimed that “the War Between the States was not a rebellion, nor was its underlying cause to sustain slavery,” from the Capitol. The University of Texas at Austin relocated four Confederate statues on its campus in 2015 and 2017. But this only scratches the surface: Statewide, only 34 of 240 Confederate symbols have been removed, including nine monuments, according to the Southern Poverty Law Center.

My great-grandfather has no monuments dedicated to him, nor do I think he deserves any. What he represents is too corrosive to memorialize.

I don’t have trouble condemning José-María as racist and acknowledging the harm he caused the Chinese community in Northern Mexico. I have come to take a qualified pride in my Mexican heritage, but to the extent it is synonymous with the racism José-María espoused, I must condemn it. Being members of a pluralistic society requires us to put our civic ideals, like the belief in human equality, above allegiance to our ancestry.

I never heard about José-María as a kid. My grandparents died when I was young, and my father never spoke of him. One Christmas when I was home, I happened upon a collection of my grandfather’s writing about our family history. His father, he wrote, had been mayor of Magdalena, Sonora, and his papers were preserved in a collection at the University of Arizona.

I looked up the collection online, which featured speeches, newspaper clippings, and correspondence, including hate mail from Chinese Sonorans. A quick trip to Google Scholar filled in his biography.

José-María was indeed elected mayor of Magdalena in 1919 after running twice, his first campaign derailed by a stint in prison for inciting violence against Chinese immigrants. As mayor, he was only able to pass laws taxing Chinese businesses, but his advocacy helped inspire the Sonoran legislature to relegate Chinese immigrants to ghettos and expel them in 1919—a move later overruled by the federal government. He died in 1921, supposedly from being poisoned, after which his widow moved to Arizona with my grandfather, where the family was reduced to poverty.

Though I think it is good to have learned about the monster in my bloodline, I’m glad that ultimately, his name will only exist only for those who want to discover it. That’s where I think my great-grandfather’s shameful legacy belongs—in the historical record, the subject of debate and reflection about the mistakes of our ancestors, as a warning of what happens when one is too proud of one’s identity.