How Climate Change Is Driving Central American Migrants to the United States

In the poor, violent Northern Triangle of El Salvador, Honduras and Guatemala, worsening floods, drought and storms are pushing a growing number of migrants north.

A version of this story ran in the December 2018 issue.

Donald Trump thinks there’s an immigration crisis at the U.S.-Mexico border. He has no idea what’s coming.

Thousands of Central American migrants arrive at the border each month, fleeing both grinding poverty and unchecked gang violence. Increasingly, they’re also escaping a threat they might never mention to immigration agents: climate change. A narrow strip of land flanked by oceans, Central America is one of the world’s most environmentally vulnerable regions. “It’s an area hit by hurricanes on both sides, rocked by volcanic eruptions, drought, earthquakes, and with accelerating climate change, it’s even more vulnerable,” said María Cristina García, a Cornell University professor of American studies who’s writing a book about climate refugees.

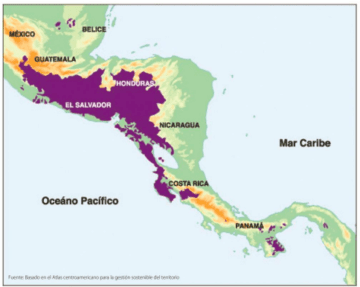

Central America hosts both spectacular catastrophes — Hurricane Mitch displaced 3 million people in 1998 — and slow-burn disasters, such as frequent droughts worsened by climate change. Many of the current crop of refugees hail from the region’s “dry corridor,” a zone afflicted by alternating drought and flooding, where farmers face crop failure even without the effects of a warming planet. The corridor falls mostly within the poor, violent Northern Triangle of El Salvador, Honduras and Guatemala — a major source of immigrants to the United States.

Recent spikes in migration have tracked with precipitation patterns. In 2014, the year of the much-politicized surge in families and unaccompanied children arriving at the border, a drought struck the dry corridor. Farmers were still scrambling to recover when another untimely drought hit early this summer, wiping out first harvests of beans and maize. Many of the asylum-seekers caught up in Trump’s short-lived family separation policy were indigenous Guatemalan farmers fleeing the specter of starvation.

The interplay between climate change and migration can be complex. Many Central Americans displaced by hurricane or drought first relocate within their home countries (a rule that holds true worldwide). They often face gang violence, marginal employment and racial discrimination. When they later flee to Mexico or the United States, García said, the original cause of their displacement is obscured, leading to an undercount of climate-driven refugees.

Nobody knows how many people climate change will displace globally. At the high end, the U.K.-based Christian Aid predicts there will be 1 billion environmental migrants by 2050. A more typical estimate is 200 million. Of those, an unknown number will cross international borders, and no country is ready to receive them. Climate refugees are not recognized by the United Nations or any government. The closest thing in the United States is Temporary Protected Status — a designation that shields migrants from deportation to areas devastated by natural disasters, which Trump is currently shredding. When it comes to refugee policy, “There’s a total refusal to deal with the reality of climate change,” García said.

Trump rejects reality altogether. In October, he claimed the climate will simply “change back again.” Still, his policies have a certain cruel logic. A flood of climate refugees is coming, and the choices are stark: Develop a generous asylum policy and mitigate the impacts of climate change with investment abroad. Or build walls high enough to stem the tide.