Holding Back the Flood

For activists in the Valley’s colonias, success looks like a drainage ditch.

A version of this story ran in the February 2016 issue.

In a bright turquoise house on the outskirts of San Juan in the Rio Grande valley, Josué Ramírez, the millennial co-director of a housing nonprofit, stood at a whiteboard with an Expo marker in hand. Around him, about a dozen people, community activists from the valley’s colonias, were seated at plastic tables, some eating homemade shrimp tamales. Ramírez’s subject was hardly riveting; he was talking about drainage, the mechanics of getting water out of colonias with little or no infrastructure at a time when extreme storms are getting more frequent. That was all too clear three weeks earlier, when October’s Hurricane Patricia dumped 11 inches of rain on the valley. In the colonias, front yards turned into lakes, and weeks later, vast stretches of still-standing water bred swarms of mosquitoes so thick that people avoided going out in the evening. Insects and vermin took refuge in people’s houses, and a scourge of skin rashes and head lice followed. Communities reeked of raw sewage, and residents believed contaminated water was the cause of a spate of stomach illnesses.

“There’s no place for the water to go,” Nelly Curiel told me. A resident of the Goolie Meadows colonia, she was among the people who spoke with me when I attended the meeting with Ramírez. “The colonias just fill up with water,” Curiel continued. “The county has to send in pumps, and until then, we’re stuck for days.”

So even though retention areas and drainage ditches are tedious topics, the people seated at the plastic folding tables were focused. They knew that if they wanted something done, they’d probably have to provide the drive themselves. Their neighborhoods are by definition neglected, designated “colonias” by the state government because they’re border communities lacking basic services, such as sewage, water and drainage systems. Colonia residents, many of whom built their homes with their own hands, are used to being thrown back on their own resources. In the case of drainage, that has meant learning about how it works and turning knowledge into community action.

Up at the whiteboard, Ramírez wrote down “403” — the number of colonias included in a first-of-its-kind Texas Water Development Board study that will assess which colonias are most in need of better drainage; the study almost certainly will also determine which neighborhoods will be first to get state-funded improvements. For Ramírez and the colonia activists, the figure represents victory, one of the first and most important wins in a battle for the kinds of infrastructure that almost everyone else in the state and country take for granted.

“In terms of building and developing communities in the Rio Grande valley,” Ramírez said, “you really have to start from scratch with the basic necessities, with issues like drainage, which in the city and more urban areas are not necessarily issues at all, because it’s actually there.”

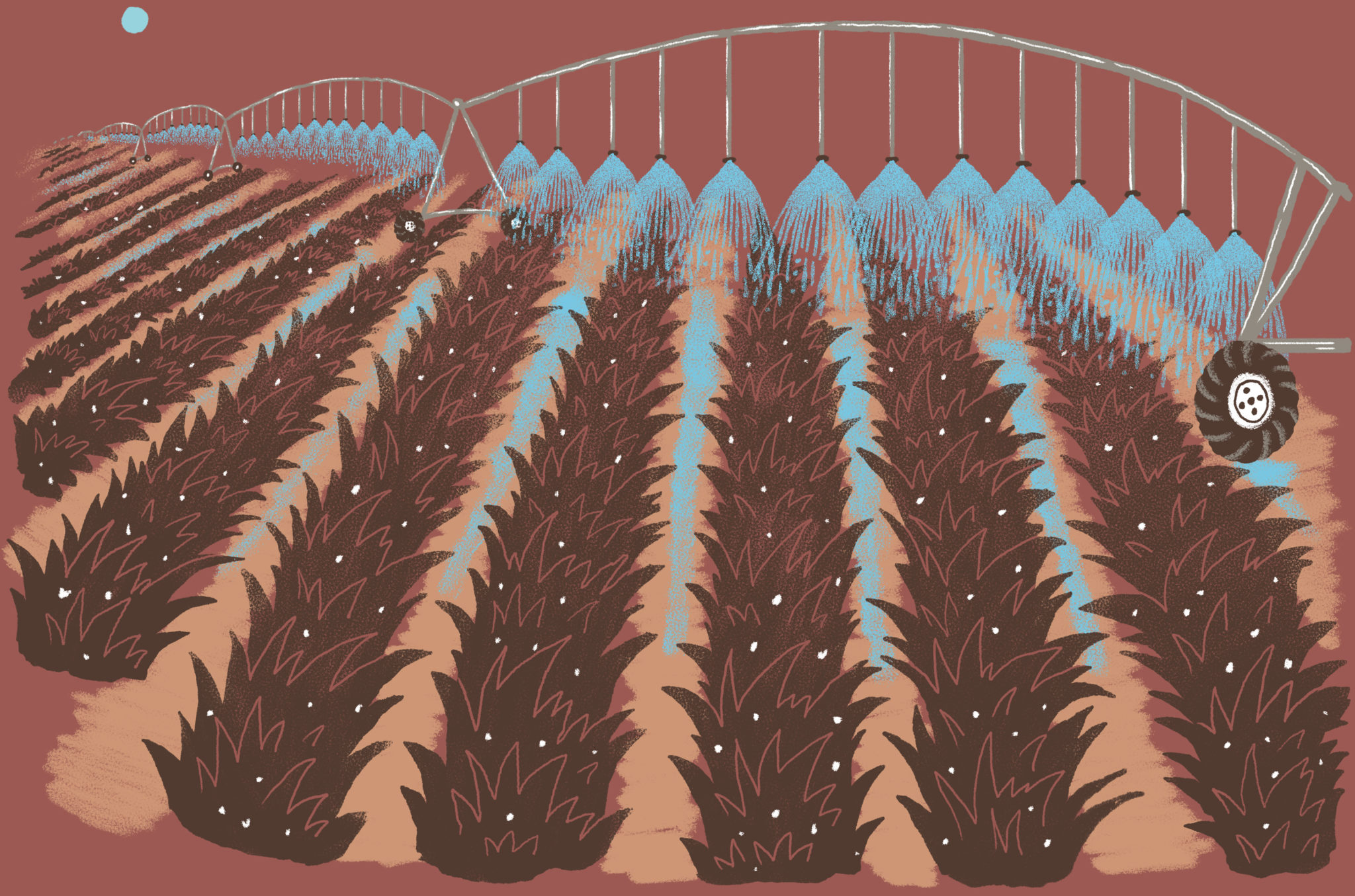

The Rio Grande Valley isn’t really a valley — it’s a delta. Before the construction of Falcon Dam in the 1950s, regular flooding deposited fertile soil that turned the region into one of the nation’s most productive agricultural areas. The resulting topography is almost entirely flat, and during hot, dry weather, the clay soil can bake into a kind of nonabsorbent terra-cotta. The valley’s proximity to the Gulf makes it vulnerable to severe storms, and the interaction of conditions creates the kind of dilemma that keeps engineers awake at night: How to get water out of the area fast.

A map of the valley’s drainage system looks like a spiderweb, with 2,500 miles of ditches maintained by local, state and federal agencies. Designed with agriculture in mind, the system has become an engineering dinosaur. As housing developments have supplanted farmland, the drainage system has not kept pace; by 2020, Hidalgo County’s population will exceed 1 million, double what it was when its master drainage plan was last revised in 1997. In a region with poor infrastructure and serious flooding, colonia residents are in the most trouble. Many of their neighborhoods were built right on top of floodplains, and while developers often promised drainage, they had little incentive to follow through, since the state constitution denies counties most regulatory powers. Without enforceable building codes, substandard housing proliferated. Many of the colonias’ 240,000 residents also lack individual resources — steady incomes, savings, access to credit, insurance.

Curiel and her neighbors suspect that disease is more rampant in the colonias, and the statistics back them up. According to Marlynn May, special assistant to the dean of Texas A&M’s School of Public Health, the rates of infectious diseases in the colonias, including hepatitis A, rubella, shigellosis, flea-borne typhus and rabies, are two to four times the average in states that are not on the Mexican border. Nearly 38,000 Texas colonia residents live in places classified by Texas’ secretary of state as “highest health risk,” and another 116,000 colonia residents live where the risk is designated “intermediate.”

Climate change brings another potential disaster to the colonias. The valley is located not only on an international border but also on an ecological one, where temperate and tropical regions meet. As the climate warms, the ranges of disease-carrying mosquitoes and other parasites shift northward. According to the Centers for Disease Control (CDC), dengue fever outbreaks have occurred twice in the valley in the last decade; most dengue infections produce relatively mild symptoms, but severe cases can lead to lung, liver and heart damage. The CDC also reports that the Zika virus, which provoked widespread fear in South America after it was linked to a birth defect that causes babies to be born with smaller-than-normal heads, has spread as far as Nuevo León, near the U.S.-Mexico border. Then, there’s Chagas disease — transmitted by the T. cruzi parasite — which researchers estimate has infected 300,000 people in the United States, many in Texas. Called one of America’s new plagues of poverty by Baylor’s Peter Hotez, the disease over time can lead to potentially fatal heart complications.

A previous big storm, Hurricane Dolly in 2008, was the catalyst for the drainage campaign launched by Ramírez and the colonia residents. After Dolly subsided, then-Governor Rick Perry attempted to shift flood-relief funding away from colonias and other low-income communities. His move prompted a Department of Housing and Urban Development civil rights complaint from the Texas Low Income Housing Information Service, the Austin housing policy non-profit where Ramírez works. In 2010, state government and the housing nonprofit reached a settlement, and $122 million in funding was returned to flood relief for the colonias. Two years later, Ramírez, who grew up in the colonias but graduated from the University of Texas at Austin, moved back home to start the nonprofit’s new valley office.

His first task was to coordinate construction of homes to replace those destroyed by floods, and in the process, he built partnerships with colonia-based community organizations and nonprofits involved in building low-income housing. After the homes were built, Ramírez and the community organizations realized they couldn’t wait until the next flood to take action. They needed to be proactive. Hence, the creation of Land Use Colonia Housing Action (LUCHA), a community organization of 11 determined, highly vocal veterans of various colonia campaigns.

“The colonias just fill up with water. The county has to send in pumps, and until then, we’re stuck for days.”

While engineers and architects put together a curriculum, the LUCHA activists, who had begun calling themselves luchistas, held community meetings, which is how Curiel got wind of the organization. For her and her husband, owning a home is a point of pride, their most important investment in the future. So when an activist stopped by to tell Curiel about a meeting to organize for better drainage and streetlights, she attended and has been a luchista ever since. “In the beginning, I was extremely shy,” she told me when I visited Goolie Meadows. “It was almost painful for me to speak in public. But I’ve developed a lot as a person. Now, I know that I have a voice, too, and that I have the knowledge to fight for the community where I live. Not only that, but I want everyone else here to know that they can have a voice, too, because so many people are like I was.”

As part of the Hurricane Dolly settlement, the Texas General Land office allocated funds for the Texas Water Development Board study of drainage needs in the colonias. There had never been such a study. Instead, residents say, the few colonias that have drainage seemed to have been selected at random. The new study was exactly what the luchistas, after looking into flooding in the colonias for two years, decided they needed.

But in early 2015, when Ramírez showed a copy of the plan for the study to the luchistas, they were incensed. Only 100 of the 1,200 colonias in Hidalgo County were slated for review. And the luchistas noticed that many of their own colonias, which they knew flooded frequently, weren’t on the list. Some of the selected colonias didn’t match the state’s own criteria: low-income and without basic services. Using GIS, a mapping system, the residents “found that some of the 100 colonias were RV resorts, or empty fields of land,” Ramírez told me. “And a lot of the places were not low-income. They weren’t really colonias. It was really a waste of resources.”

For the luchistas, the selection of colonias represented disaster. If the colonias with the worst flooding weren’t included, what was the point? And the reason for the oversight was plain enough to them. “They were doing all of these studies about flooding and drainage,” said Norma Aldape, who lives in a flood-replacement home designed by bcWorkshop. “But they were only based on what the computer said. They weren’t physically going to our colonias, so they didn’t really know what things were like on the ground.”

The luchistas hatched a plan. With the help of Ramírez and state Senator Eddie Lucio, D-Brownsville, they arranged meetings with engineers from the water board, and in advance, they gathered ammunition. Traveling across the valley, they photographed colonias that flooded regularly but weren’t among the 100 selected, as well as places that were selected even though they are wealthier subdivisions or sparsely populated areas. From the photos, they created postcards that were distributed to more than 500 families. The families, in turn, wrote their own complaints on the backs of the postcards, then mailed them to the water board. That got the agency’s attention. The board’s engineers worked with the activists to distribute surveys about local flooding, which were then used to determine areas that would be included in the new study.

“LUCHA has been beneficial in making sure that no colonia was left out [of the study],” said Gilbert Ward, flood mitigation grants coordinator at the water development board. “They’ve helped organize meetings, turn out colonia residents and gather their input, and then keep them updated on the study’s progress.”

At the November meeting I attended, the luchistas found out that they had won the first salvo. With increased funding from the General Land office, the study was expanded to include more than 400 colonias, all low- to moderate-income communities with documented histories of serious flooding. Ramírez wrote another number on the whiteboard, “20,” which represented a second win. Water development board engineers had already designed drainage projects for 20 colonias, those with a combination of the worst flooding and the easiest solutions, like nearby drainage ditches.

“It’s an injustice that we pay our taxes like everyone else, but we don’t have drainage. We have a right to these services, and we don’t need it sometime in the future.”

“Our work is only just beginning,” Curiel told me. “It’s an injustice that we pay our taxes like everyone else, but we don’t have drainage. We have a right to these services, and we don’t need it sometime in the future. We’ve been fighting for it for years. We need it now.”

The Spanish Palms colonia is in about the same shape as Curiel’s neighborhood. Houses lack not just screens but also windows; to add bedrooms, residents have built wood-frame additions onto decaying Rvs. only here, change is in the works. Under an $84 million Hidalgo County drainage bond, a small percentage of funds is available for residential improvements, and Spanish Palms was chosen because it’s only yards away from a new drainage ditch the county is building. So as Ramírez and the luchistas lobbied engineers for a bigger and more accurate study, they also took a step further. They started working directly with bcWorkshop to design drainage systems tailor-made for colonias like Spanish Palms.

On a windy day in November, I arrived in Spanish Palms to meet Hugo Colón, bcWorkshop’s landscape architect. He emerged from his car carrying a collection of documents. A native of Puerto Rico, he graduated from the Harvard Graduate School of Design. As a posse of dogs announced our presence to the neighborhood, he told me, “I was already bit here once but not too badly.” Then he unfolded one of the documents and spread it out on the hood of my car. It was a schematic design for a new drainage system that would connect to the county’s new drainage ditch, allowing water to empty out of the colonia. Without the connecting system, the county’s new drainage ditch would be useless for the community.

Prior to drafting the design, Colón had attended a series of meetings in neighbors’ driveways. There, they’d discussed the advantages and disadvantages of conventional and low-impact drainage systems: Using the former, concrete drainage ditches move water quickly; with the latter, ditches are lined with native vegetation wherever possible, so water naturally filters down into the groundwater. “Water can be a challenge,” Colón said, “but it also can be an opportunity. For us, it’s very important to address not only drainage, but also quality of life.”

In the end, the design produced by bcWorkshop, which will use drainage ditches lined with plants, will change the entire community. To make the system work, streets will be narrower, and there will be new, landscaped open spaces at the entrance to the community. Colonia residents had taken the plan to county officials, and construction was now underway, as evidenced by the freshly upturned earth running along the street. For colonia residents, having the design in hand had been key in convincing the county to fund the project. Colón hopes that in the future, other colonias for which he’s designed plans will build on the success in Spanish Palms. “They can say, ‘We have this problem in our community, but we also have a design that we’ve produced with the landscape architects,’” Colón told me. “Which is powerful. They don’t go empty-handed. They have a plan.”

For now, bcWorkshop is working on getting native plants donated for the open spaces, and residents and the luchistas are organizing a planting day. The next time there’s a heavy storm in Hidalgo County, at least the Spanish Palms colonia may not flood.

As we walked with the dogs alongside the new ditch, an elderly woman approached us, leaning over a walker. She told me her name, Doña Manuela, and invited us into her driveway. Active in community organizing for decades, she’d hosted some of the drainage meetings right in the spot where we were standing. “You don’t know how happy I am,” she told us. “It’s been worth the fight — all these years, all of those commissioners meetings I sat through. Look,” she said, turning her gaze towards the ditch, then back at her house. “This is my reward.”

To support journalism like this, donate to the Texas Observer.