Concrete Ideas

New technology and methods may help clean up the cement and concrete industries—two of Texas’ most conspicuous polluters.

It’s a concrete world, and we’re just living in it—or so Texas cities feel to many residents. Some uses of that omnipresent building material seem questionable, like fueling the seemingly endless expansion of state highways. But others, like building more housing and businesses, help accommodate a growing population.

The industry touts concrete as “the most abundant resource in the world” after water. Of course, that’s not counting intangible resources like the air we breathe and rely on to keep our planet habitable.

Concrete’s ubiquity poses major air quality problems. The end product itself isn’t the biggest issue. Making cement, an underlying ingredient in concrete, requires burning massive amounts of fossil fuels and releasing additional greenhouse gasses as a byproduct of the chemical process. New research shows greenhouse gasses released from cement production have doubled in the last 20 years and currently account for 7 percent of global carbon emissions.

Much of this increase relates to China’s explosive economic growth and development, but the United States plays a major role, ranking 5th worldwide in cement-related emissions. And Texas produces more cement than any other state.

Midlothian, a city of about 30,000 just south of Dallas-Fort Worth, hosts three of Texas’ seven enormous cement plants. Jane Voisard, a local resident and activist with the grassroots group Midlothian Breathe, describes her community as a company town. The city even used to advertise itself as the “Cement Capital of Texas,” but Voisard said local officials have wised up.

Greenhouse gases aren’t the only form of pollution residents like Voisard worry about. Cement plants also release carbon monoxide, particulate matter, and volatile organic compounds (VOCs) into the air. Although it’s hard to prove a link between community illnesses and nearby pollution, areas around Midlothian have significantly higher childhood asthma rates than the national average. A 2012 study from the University of Texas at Arlington showed most children diagnosed with asthma in neighboring Tarrant County lived directly downwind of Midlothian’s cement kilns.

While the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality (TCEQ) recently set up an air quality monitor in Midlothian, it placed the device upwind of the cement kilns. Voisard called the situation the latest “Catch-22” the community faces in trying to hold the three cement companies—Holcim, Martin Marietta, and Ash Grove—to account. “It’s just a travesty. It’s terrible,” she said.

While cement industry officials seem less willing to acknowledge the health effects of process-related air pollution, some are acting to address the climate change problem.

Companies are slowly improving, said Josh Leftwich, president and CEO of the Texas Aggregates and Concrete Association. For example, leaders of CEMEX, a Mexico-based multinational corporation that operates cement plants in San Antonio and New Braunfels, have set a goal of becoming “carbon-neutral” by 2050. So have the leaders of Holcim, a Switzerland-based multinational. (Scientists around the world agree that to avoid truly catastrophic climate change, the global economy must be carbon-neutral by then.)

The industry has a long way to go. One incremental step most Texas companies have taken is switching to a type of cement called “1L,” Leftwich said, which produces approximately 10 percent fewer carbon emissions than traditional Portland cement—a significant improvement, but far from carbon-neutral.

With concerted effort, those companies could get there. Available technologies have improved substantially, said Robbie Andrew, a researcher at Norway’s Center for International Climate Research who compiled a recently updated dataset on cement emissions. Just a few years ago, cement was the “poster child” of a carbon-spewing industry, he said. “But now we have lots of options that we think down the line could reduce those emissions substantially.”

Some facilities already have switched to biofuel for operations, although they generally still must use some fossil fuels, Andrew said. Companies could also use less “clinker,” a grainy material made by heating up limestone and clay that’s responsible for most of the greenhouse gasses that result from cement production. Some places are substituting fly ash or blast furnace slag, byproducts of power plants and metal production, for some clinker in their cement mixes.

Other futuristic-sounding but real options include deploying plasma torches, which use electricity to turn gas into plasma, to help solve the problem of generating enough heat to produce clinker, and therefore cement, without fossil fuels. Handheld plasma torches are already widely used to cut metal. There’s also the emerging option of capturing and storing greenhouse gasses produced while making cement. The federal Department of Energy is currently putting millions of dollars into pilot projects for carbon capture at industrial facilities nationwide.

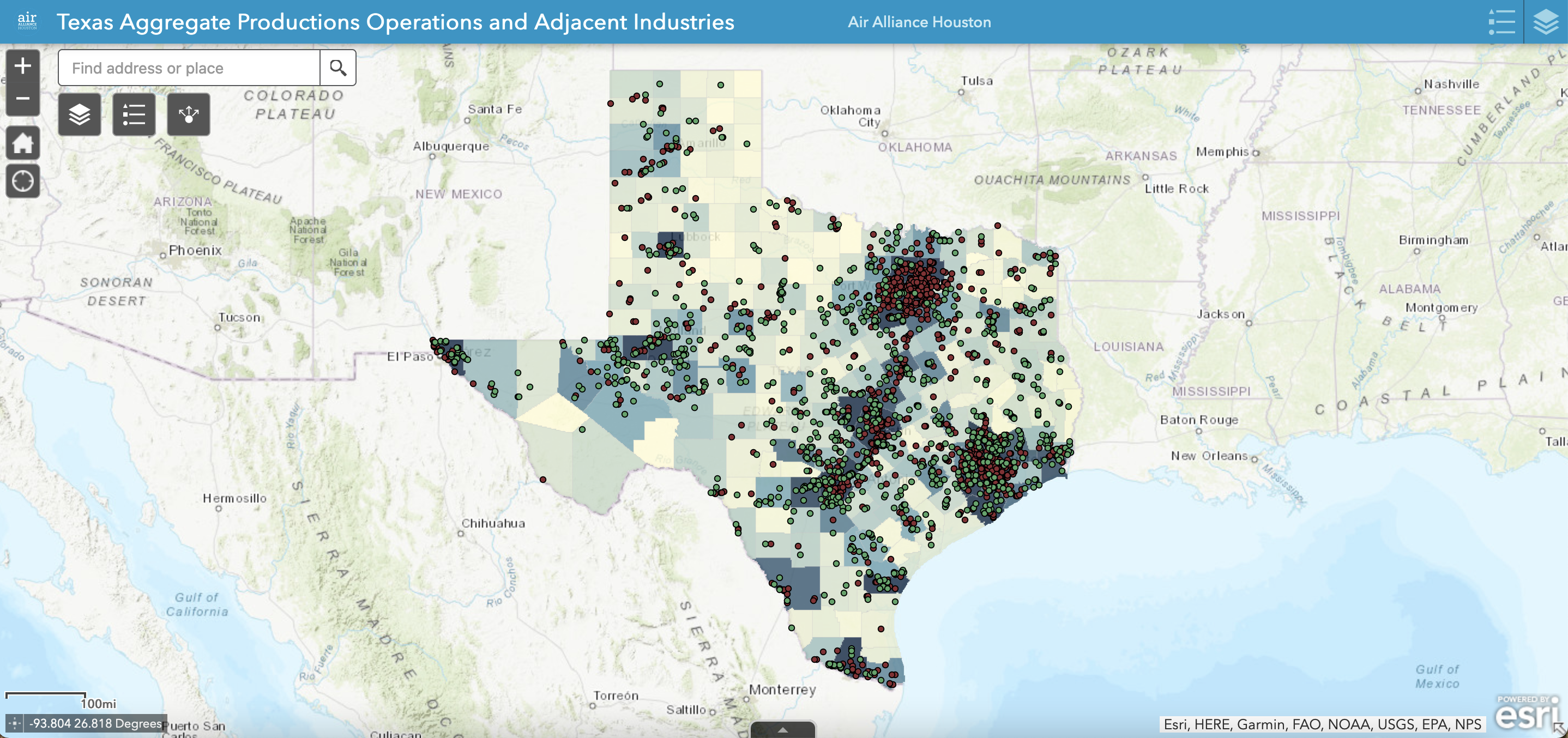

These solutions, however, don’t address the other forms of air pollution that local citizens and public health advocates associate with both cement and concrete. Most cement goes into making concrete, a separate process with its own set of environmental issues. While Leftwich said that concrete batch plants—which mix cement with sand and gravel to produce “ready-mix” concrete that’s then sent to construction sites in trucks with rotating drums—are not supposed to emit much pollution into the air, without vigilant maintenance they do often release particulate matter. The facilities also become hubs for diesel trucks, which release their own pollution.

Concrete batch plants drew the most complaints of any industry in a recent public hearing on TCEQ, the state’s main pollution regulator.

Grace Tee Lewis, an epidemiologist at the Environmental Defense Fund, draws a throughline between the local health problems caused by cement and concrete facilities, and the global problem of climate change these companies also fuel. Communities that host a lot of industrial polluters face a vicious cycle of environmental and health issues that can be exacerbated by climate change effects like flooding and heat waves.

“They are typically the same communities that are impacted time and again. They are the ones that are first and worst and most frequently impacted, whether that be by natural disasters or man-made events,” Lewis said.

In Houston’s historically Black Fifth Ward—which was hit hard by Hurricane Ike in 2008, then by Hurricane Harvey in 2017—residents have been vocal about the disproportionate air pollution they face. They are constantly fighting against permits for more concrete batch plants in their neighborhoods.

“It’s not like we choose to breathe. We have to breathe,” said Leticia Gutierrez, the government relations and community outreach director of local advocacy group Air Alliance Houston.

TCEQ is generally quick to hand out permits for concrete batch plants, so Houston and Harris County residents are putting pressure directly on companies. In 2019, one company voluntarily withdrew its application for a new concrete batch plant near Houston Mayor Sylvester Turner’s house after public outcry. In that case, the mayor himself rallied other local officials to oppose the permit. Gutierrez says her group is taking lessons from that fight for future permitting battles, but it would help if TCEQ more closely scrutinized applications—including accounting for the cumulative effects of multiple polluting facilities in one neighborhood, and setting stricter pollution limits in line with the latest science.

Enacting reforms could push companies to make sustainability a selling point. The Texas Aggregates and Concrete Association’s Leftwich said that with the state’s growing population, and government investment in infrastructure, demand for his member companies’ products is at an all-time high. “Right now, the competitive standpoint is: ‘You got something you can deliver today, or tomorrow?’” he said. “Until the market sets standards around [lower-carbon products], it’s not going to be pushed from a competitive standpoint.”

Up in Midlothian, activists with Midlothian Breathe recognize the economic importance of the industry and don’t necessarily want the local cement plants to close. They simply want the operators to be more “responsible” partners in the community, Voisard said. In the meantime, her organization has started setting up its own air monitors around town. If the data shows cement plants are exceeding EPA pollution limits, residents could take legal action.

But with technology improving, industry leaders could simply choose to do better without waiting for lawsuits or regulation to address climate change and other concerns.

Besides adopting the many emerging solutions for cement, companies could also start adding graphene, a material first produced in 2004, to their concrete mixes. Graphene is made from a single layer of carbon atoms arranged in a honeycomb pattern, and despite its seeming fragility is 200 times stronger than steel. Andrew from the Center for International Climate Research explained that adding graphene makes concrete stronger, meaning construction projects require less concrete to accomplish the same goals, and therefore pollute less along the way.

“Things are changing,” Andrew said. “Before we start, everything seems really, really difficult. But when we just get started and put our minds to it, then it seems like solutions just keep popping up. Innovation just keeps introducing new ways to solve this crisis.”